Questions answered – Shoulder planes a Misnomer?

Hi Paul,

Quick question for you (you may have gotten this one before.) What is your take on shoulder planes? I am a new-ish woodworker and I’m trying my very hardest to get into hand tool work, but one of the things I am struggling with is how to prioritize the tools that I buy.

The shoulder plane seems to be in the “optional” list for most. I struggle getting seamless joints in my mortise and tenons and I thought a shoulder plane could help with that. What do you think? Unnecessary? I’ve been told you can clean up tenons (cheeks and shoulders) with only chisels but I find it a bit challenging.

Since you don’t have any entries on shoulder planes I thought I would just ask to see if you have any and if you think they are worth having in the kit.

Best Regards,

Lucas

Additional reading

Before I go further, to address other comments from your email, I suggest you go through my series on buying good tools cheap, and here is a starter point for you if you haven’t already gone through it. Another series on Minimalist woodworking is here too. This could at least short circuit some of your search for necessary tools in these early stages. I also recommend woodworkingmasterclasses.com , here you can see some of the tools I use in action in my day-to-day-work. You’ll be surprised to see just how few I actually use, even to make masterpieces like the pieces I made for the White House four years ago. Don’t get confused by the subscribe button, hit it, this gets you in for free aspects of the masterclasses we teach here as when we teach any techniques such as saw sharpening or building a shooting board we always make it for free. You just need to sign in. I think you will find it worthwhile.

Historical perspective

Historically, these planes were popular for two or three main reasons; low-angle bevel-up presentation, heavy weight for steadiness, and long tenon shoulders we generally no longer make.

As a boy I loved looking inside the tool chests underneath the benches of my then mentoring craftsmen. Two fall-front joiner’s chests side by side was pretty standard at each of the benches and possibly a lift up lid box, which usually held matched sets of hollows and rounds together with a few more essential moulding planes, some larger saws and more awkward tools like wooden plough planes and routers (non machine unplugged). I loved touching the the ebony and brass shoulder planes that glinted when the box lids were dropped. Pulling them out and seeing the owner’s name stamped on the end grain and even on the brass itself, Merlin Bates, Bert Pugh, George Mycock and Jack Collins always showed me the regard they had for their more prized but then less used tools. These were men I admired and respected for their skillful workmanship and their humility. Just workmen I know, but respect was very present in those days.

Why were these planes popular?

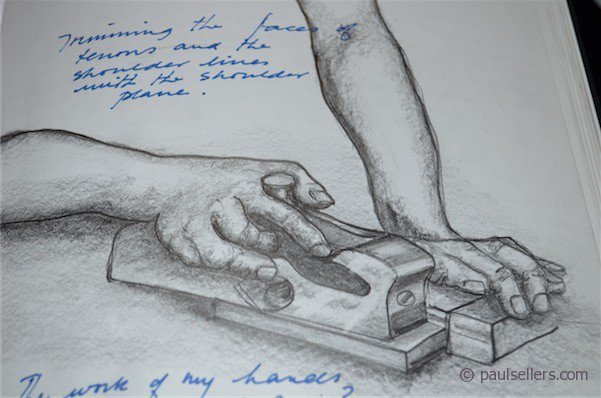

Now then, where does that leave the shoulder plane for today’s woodworkers when wide shoulders are the rarity and not so much the norm? As you rightly point out, these planes fit nicely in the “optional” plane list – for the main part that is. Personally, I wouldn’t relegate them too far down the list though. You may have seen that I surface tenons using a router plane, so that the tenon remains perfectly parallel to the surface of the main rail. I like to plane these tenon surfaces just enough to leave them a little ‘fat’ by a fraction or two. Then this is the point where the shoulder plane works to perfection and I mean to perfection. A 1” or so wide shoulder plane when, set perfectly, will take of a thousandth of an inch 1” wide in a single swipe. You will achieve perfect tenons to almost immeasurable perfection when you do this and the tenon looks just beautiful.

What about shoulders?

The title of the plane may well be a misnomer. I saw it used as much for the cheeks of tenons as I did for shoulders and so it may be confusing to call it anything else even though it was used for both aspects of truing tenons. Not all shoulders and cheeks can be trimmed with this plane because the size of the tenon made such a difference. The plane is hard to register on skinny shoulders over short lengths. It isn’t just the sole that needs to register but the side of the plane too. Both work in tandem to direct and control the plane. So, working on a 1” long by 1/4” shoulder doesn’t generally work that well.

My drawing above is roughly a Canadian Veritas shoulder plane that I use and like to have and can highly recommend. There are other makers too, Lie Nielsen in the US and Clifton in the UK. Beyond these production makers there are highly engineered planes for the collector-user that cost the proverbial arm and a leg. Dovetailed soles and sides in brass and steel and all that. They are not really so much necessary, but they too work just fine. And then of course there is eBay and the secondhand market where you can buy a good old Record or a Preston. Choose your weapon!

An interesting article about shoulder planes, thank you. I see you write about the metal and infill planes. These rarely have a skew blade. I have two old wooden rebate planes with skew blades, that I would use for similar work to the shoulder plane. Do you have an opinion on those? I inderstand the issue of bevel down and low angle bevel up, but the skew helps a lot when working across end grain.