Old Men, Old Planes, Old Ways Now Gone – The Origin of Scrub Planes

This Blog Post is About Scrub Planes.

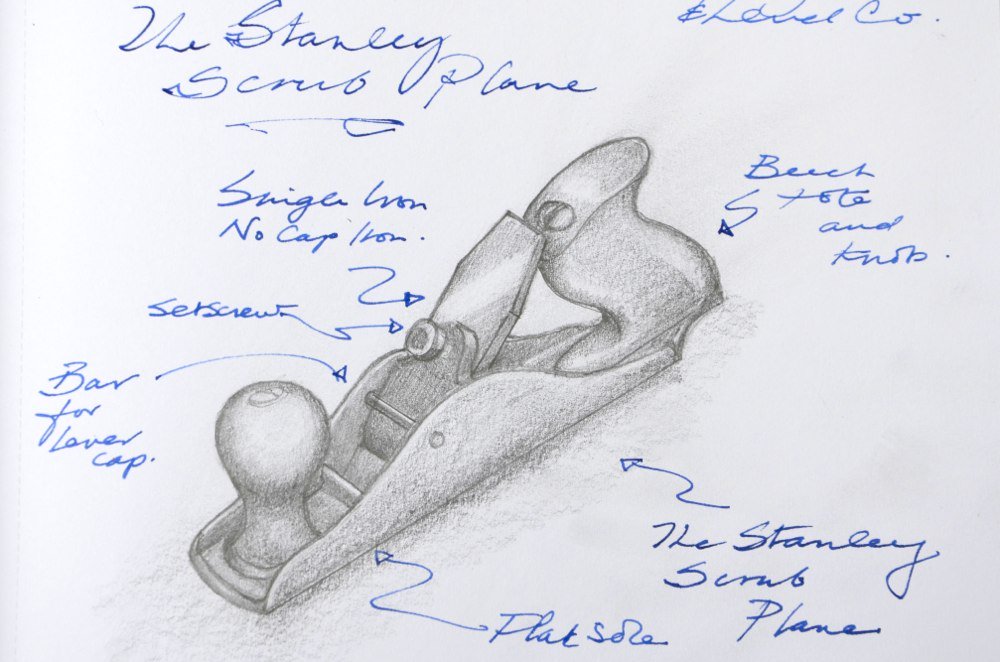

Had I said roughing planes, only a few would have understood. Even in the 1960s old wooden planes, the Stanley scrub plane and even the Stanley furring plane would have been referred to as roughing planes because, in typical fashion, the plane derived its name from its function.

In my dim and distant past (yes this is me 25 years ago or so) I worked with many men 40 years older than myself and all the way up to being 80+ years old. My personal tools then were all squeaky new of course, but the tools in the tool chests and joiner’s boxes these men treasured were all very, very old. Older even than them. I don’t think I was even remotely capable of seeing then that the value in these tools could not be appraised in monetary value but by the provision they were to the men from two world wars in making everything from children’s toys to fine furniture and door frames to coffins. Today, 50 years later, I understand their real worth.

I Keep Old Tools to Work With Because They Work; Not Because They Look Nice

Today many planes from the past are somewhere near to my bench and the throats vary according to use. It’s here that I want to share something i think has value to us as woodworkers. It’s a little bit about the history of planes that may offer insight. In time past I have shared that old wooden planes were never abandoned because they didn’t work or indeed work well. They were abandoned because they didn’t keep pace with the industrialising of craft and the art of work. The whole process of plane making was an art that required great skills in both woodworking and metal working to make the tools of the plane maker. The wood too required specific parameters to produce tools that would remain stable. Though wood was dried in large quantities, distilling this down, a plane blank for your average bench plane, regardless of length, would at very minimum be 5 years before the plane would come from the hands of its maker.

For Centuries Woodworking Craftsmen in Different Trades Made Their Own Planes and Tools

Though wooden plane making ultimately became a specialist woodworking trade within the realms of carpentry and joinery, this only happened after centuries of craftsmen making their own planes according to their given trade. Coopers and wheelwrights, joiners, carpenters, boat builders and 50 others all developed their own specialist planes and tools. Making a plane was a 3-4 hour process and from new the plane served its maker for many decades.

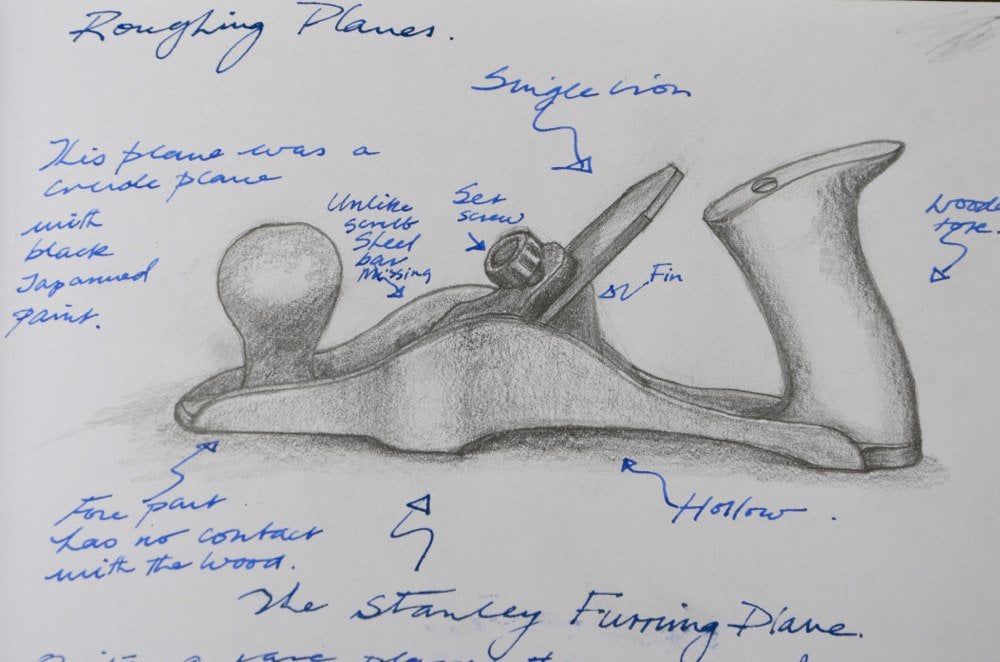

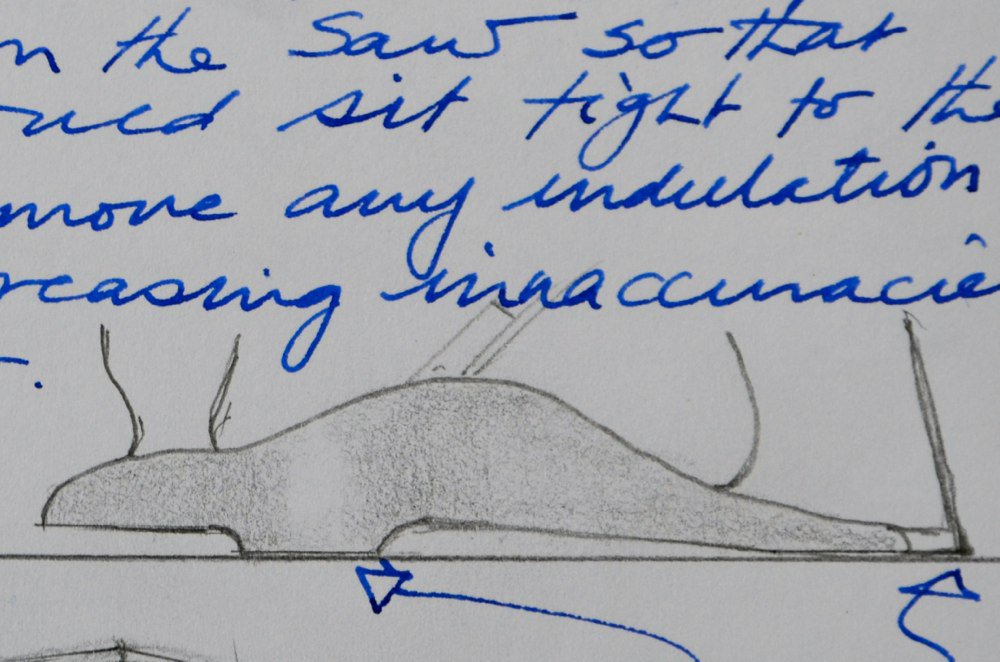

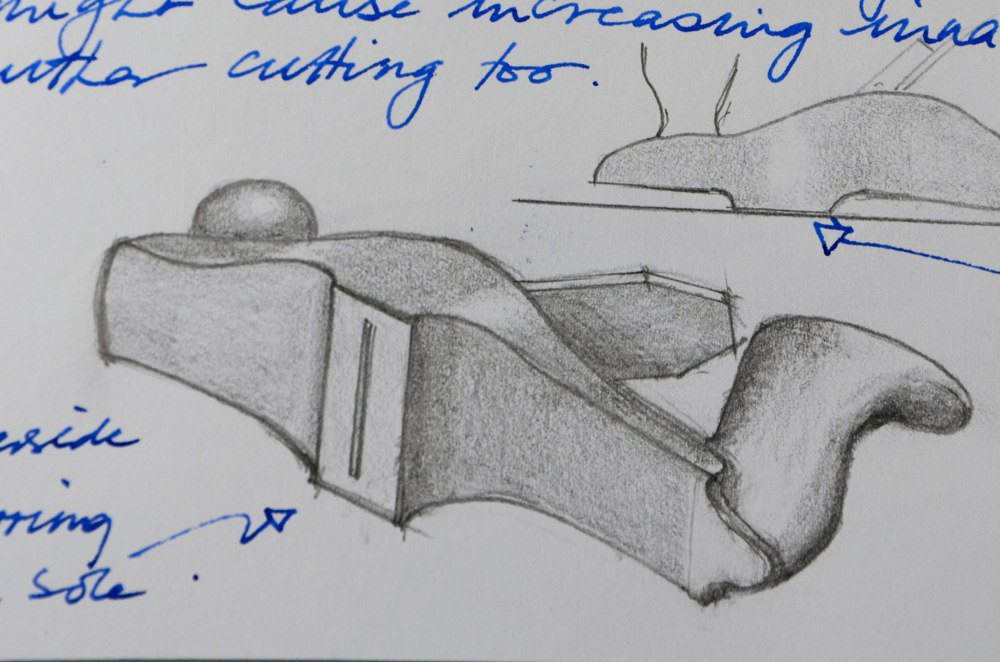

This Image Shows Progressive Stages of Wear and the Resultant Throat Openings Culminating in a Convexed Blade Intended for Roughing.

The Evolution of the Roughing Plane

In the beginning the plane started life as a plane with tight tolerances. Cutting edges were bedded only 1-2mm from the front aspect of the sole , which created the closed throat needed for fine shaving work. Such a plane brought into service for close and fine work would work for a decade or so before wear began to take its toll. It made sense to create a new plane alongside the more used one as the wear became apparent but before too much wear took place. That being so, the new plane would run alongside the older in tandem in the same way a shepherd runs a new dog alongside the old so that he’s never without a dog. As the original plane sole became worn and needed truing because of wear and unevenness, the mouth opening became marginally wider and more open. Another decade and the mouth would be too wide for fine work and so the second plane began to replace the first. It’s at this point that the craftsman transfers the original plane to its new work working the distorted surfaces resulting from air drying wood and saving his finer plane for finer work. The cycling continued and three or four small smoothing planes would see a craftsman through his decades as a working craftsman.

Wooden Planes Performed Exceptionally and Were Never Replaced By Anything Better

Now then, try to remember that these wooden planes were not simply old fashioned models being replaced by something better and newer. That wasn’t the case at all. Also try to remember that they weren’t called scrub planes as we know the term either. They did however perform the same task. It’s important to know that woodworkers were using wooden planes for these different tasks for centuries and that they were in no way inferior to anything produced with modern-day all-metal planes. These crafting artisans in wood resisted the introduction of the all-metal cast iron and steel planes with legitimate cause. The reason they resisted the new planes was not that they shunned change for the sake of it or were merely nostalgic, but that their wooden planes were, in their hands, flawless designs in functionality in every way and actually worked better than the new all-metal ones.

Ultimately, planes with large and open throats could scrub off masses of wood.

The Scrub Plane Emerges

So, as you can see, when the wooden planes were ousted by the cheaper alternative all-metal ones that required only assembly-line production, it became only a matter of time before one replaced the other. Add into that the demands of a world war on timber resources for every aspect of industrialism and you suddenly begin to see how the demise of the wooden bodied planes took place. Machining in woodworking lessened the demand on hand methods too, to the point that one, by one, the wooden planemakers of Britain and Western Europe began dropping like flys. In tandem with the demise the need for a roughing plane made from metal was needed to replace the wooden versions. Remember there was no secondhand market for planes as we might know it now in the sense of family members selling off their great grandfather’s old stuff and certainly no world wide web. The term scrub was most likely in use long before Stanley came developed their version in the all-metal scrub. There can be no doubt that Stanley adopted the descriptive name and so created a special plane in a category all of its own. Though still a crude looking plane compared to all others, the Stanley scrub could initially be mistaken for a very unique and different plane altogether which is the much rarer Stanley #340 furring plane.

We Lose the Art and Craft of Plane Making

In all of this we saw a close to an era; a tradition of craftsmanship destined to die, save for one or two lingering makers who continued into the early 1960s. For a few decades wooden plane making died and became extinct and to a great extent that has remained the same. Two or three individuals in the USA and the UK have become independent planemakers intent to develop their own niche market for making and selling wooden planes made by hand. There are enough collector users to keep them in business.

Hello all, I have given these guys a plug before and I will again because I have been using one of their smoothers, block and shoulder planes for more than a few years . HNT Gordan is an Australian manufacturer (surprising I know!) so if anyone is interested in new wooden bodied planes I recommend them in terms of quality and service.

Thanks so much, Paul!

I have a metal plane that I thought was a cheap crappy #3 copy, but now I know that it’s in fact a scrub plane.

Yes Gav. I have been wanting a HTC Gordon for a while now. Beautiful planes. I might have to buy one at this year’s working with wood show. I better start saving.

HNT. Silly autocorrect on phone.

In Germany, where the iron planes never were popular, there are still at least two manufacturers: Ulmia and ECE.

Hello!

In Germany we still have Ulmia Ott and ECEmmerich.

Both known for quality.

Buying new costs as much as all metal planes, but used ones can be found on ebay, sometimes for little more than shipping.

I agree that the old wooden planes work great. The British wooden planes didn’t start declining in quality until around WWI, and the quality didn’t decline that much. In contrast, the American Wooden planes started a slow decline around the middle of the 19th century and were pretty much put out of business by Stanley by the end of the century. Consequently, the 19th century British wooden planes are of much higher quality than the American wooden planes of that era, in my opinion. However, both can be made to work very well if set-up properly.

Paul,

Thanks for the history. You were a dashing fellow! Great picture.

Love the photo. Can you tell us something about it and the tools and work at hand?

Thanks for the historical perspective. I continue to be an active user of these old wood bodied planes for many of the reasons you state-it is a different feeling, and they can work so well. In addition, they have another attraction. Using these old planes, they are often discolored where they were gripped for use by generations of craftsmen before me, sometimes there are even subtle depressions worn by their hands-making furniture with them using the ways you teach so well is another link with the craftsmanship of the past. “Some things are lovely, warm still with life….of the forgotten men who made them,”-DH Lawrence.

I loved your article and can now understand better the historical evolution of wooden planes in the workshop after extended use and the historical replacement of wooden planes with metal ones during the industrial revolution.

I think in understanding the wooden plane’s and their relationships with joinery etc. we will better understand the work of craftsmen two centuries ago, and why it is superior to our own current work.

How fashions change, 25 years ago here’s a picture of you in a proper woodworking apron, with your best tools on show in a pristine studio shot.

Nowadays a more casual self portrait is more acceptable.

I suppose a Stanley plane in your hand would of been inconceivable then whereas now its a valuable classic design

How times change but craftsmanship, skill and pride in work remain unchanged thankfully.

Paul,

I notice in the picture above you wear your wedding ring on the left. In the videos you post now, I see you wearing it on your right.

I know a chap who’d put his ring on his other hand to help him remember something important.

I noticed that too. Or even more so I noticed the way he is holding the plane. I really think the photo must be reversed. I noticed it on Pauls fb page as well. Lots of comments on the photo but no one else seems to have picked this up which is surprising with so many other woodworkers commenting. Maybe the photo was reversed for publishing in the magazine and they thought it looked better for layout or something?

What’s the story Paul? Are we the only ones who picked this up?

I’m sorry, I can’t remember.

Paul,

It seems, ys, that the picture has been flipped.

3 hints :

– the way the plane is hold

– the ring at the left had (you wear it normally on the right one)

– the watch (only a small part), on the right hand which also, for you is unusual.

My good friend James (Irish Middle Name) (Irish last Name) grew his hair and beard much like yours in that photo after he mustered out of the Navy. He married a nurse who worked in a Kosher Jewish nursing home (her name was just as Irish, as they both most assuredly were).

When he went to the nursing home to pick up Eileen at the end of the day, the Jewish ladies who lived in the nursing home would invariably slip him a dollar bill.

He found out after some time that it was the hair and the beard that brought the dollar bills. They thought he was a Rabbinical student, and it was a custom hundreds of years old to give a Rabbi-to-be a small gift of money.

You worked in the wrong neighborhood, Paul.

This made me laugh! Tonight is the Jewish holiday of Purim, and traditionally we dress up in costumes and make merry. (Some of us have Irish surnames, by the way… 🙂 )

I’ll be at synagogue tonight sporting a cap and an ersatz beard and holding a plane.

Jacky Griffin

Apologies for silly questions, as I’m new to hand planes ,but am hooked.

I notice that some coffin planes have a chip breaker, and some just a single iron. Is this to do with the age of the plane, or quality/ price of the tool?

Is there any way you can roughly date coffin planes? And when did they stop making them? I’m guessing that there must have been a stage when if you got out your coffin pln youngsters would have sniggered into their cuffs at the sight of them. Between the wars perhaps?

One last question. How on earth did they make these in the early days as they’re made with such precision?

Thanks

Well, there is no doubt that the skills of planemaking were at their pinnacle between the 1700s and the early 1900s and that there were indeed hundreds of highly skilled makers here in the UK at least. There are one or two makers making planes today but offer only a limited assortment and the waiting list is long. I like wooden planes and have a large collection of them but for my daily work I rely on the more modern models designed by Stanley in the late 1800s. They are fast and efficient in my work, readily set and sharpened and they have the thin irons that sharpen so well. Single iron planes rely on thickness to quell the rebellion of chatter. The clever insight of early English makers in adding the second iron finalised the design and no maker in 200 years has ever improved on it though some claim to. Most single iron planes, those with no cap iron, were bevel-up planes and needed thick irons for resistance to flex. Older irons in older wooden planes were tapered from the cutting edge to the top. This feature gave thickness where it mattered and resistance to the pressures of planing when thrusting the plane along the wood.

I have one short wooden plane that is reserved and set for quick champhering. Works great for that. It was $6.00 at local in door market.

Steve

Paul,

Out of curiosity what is your opinion of Stanley transition planes (metal upper and wooden lower for the sole)? I ask because often the standard Stanleys that you see of the all metal design often run significantly more expensive than the transitional pieces at antique shops. I always thought it was based on them being inferior in durability and accuracy to the metal sole but now I’m thinking it could be people like me are more intimidated to maintain them. Would you compare them in quality of work produced to the full metal bodies?

Thanks

Jeremy

Transitional Stanleys are very nice. I never understood their demise.

is there any way to tell if a hand plane is bevel up or bevel down? I recently inherited a couple of planes and have spent hours trying to adjust them I never realized that the bevel could be up. Is it possible that they are worn out?

I know that my biggest problem is lack if knowledge about these tools but I would like to learn how to use them but right not it is too frustrating thanks

The easiest way is to look at the plane from the side. If the bed that the blade lies on is 40-45-degrees then it is a bevel-down plane. If if it is lower, commonly around 12-20-degrees, it is a bevel up. All Stanley and Record bench planes are bevel-down lanes as are all wooden-bodied planes.