Seeing the Art in Hand Planing—Part II

It’s a funny thing, and I have done it myself, when people swipe off shavings to prove a plane works. Most of it is quite unreal as no one really just swipes of shavings one after the other from one end of a board to the other and equally across the width of a 12″ wide board. No one. Usually it’s the grain that dictates otherwise, unless you’ve picked out this absolutely knot free, straight grained board with no grain variance in any odd direction from the long axis of the true. In the real world plane work demands much more because the wood is so demanding. So if you think that all others demonstrating such mastery and the problems you’re having are all down to you, you’re probably being hard on yourself. The reality is more this. And I have watched them behind the scenes in places around the world. Often they are there to show you such good work because they are selling something. When you’re selling something you don’t want to seem like you’re struggling at all. The best way to avoid struggling is to spend time focussing on one thing and one thing only. How to get the blade as dead sharp as possible. Spending half an hour in this unreal realm will be well worth it if you can make yourself look good and someone else look bad enough that they just have to buy what makes you look that good. Pick the right wood, sharpen the right plane and you have the ingredients for making yourself look like you are in control. And remember. the camera always lies!

OK. What am I saying? Well, in my experience, and you may have heard me say this many time, life is like wood, it comes with knots in it. I said this first. It’s my phrase and my quote. In my experience it is quite rare to plane wood that has no knots or grain that once surrounded knots somewhere in the fibres of just about any board. That being so, and it is a fact, there is bound to be grain that is with you and grain that is against. Grain that twists and turns 10 times in two inches and grain that rises straight up right when you least expect and least want it. This true in most woods but is worse in others. Try hand planing yew or beech. Sometimes that plane just glides over the surface and shavings ripple up from the mouth of the plane like butter wouldn’t melt in its mouth. Right when this happens the grain shifts and there is a 1/8′ deep tear out that just cannot be repaired. This happens to everyone other than those selling planes or plane irons or woodworking classes. In real life wood grains tear no matter which plane or technique or wood you use. Get over it.

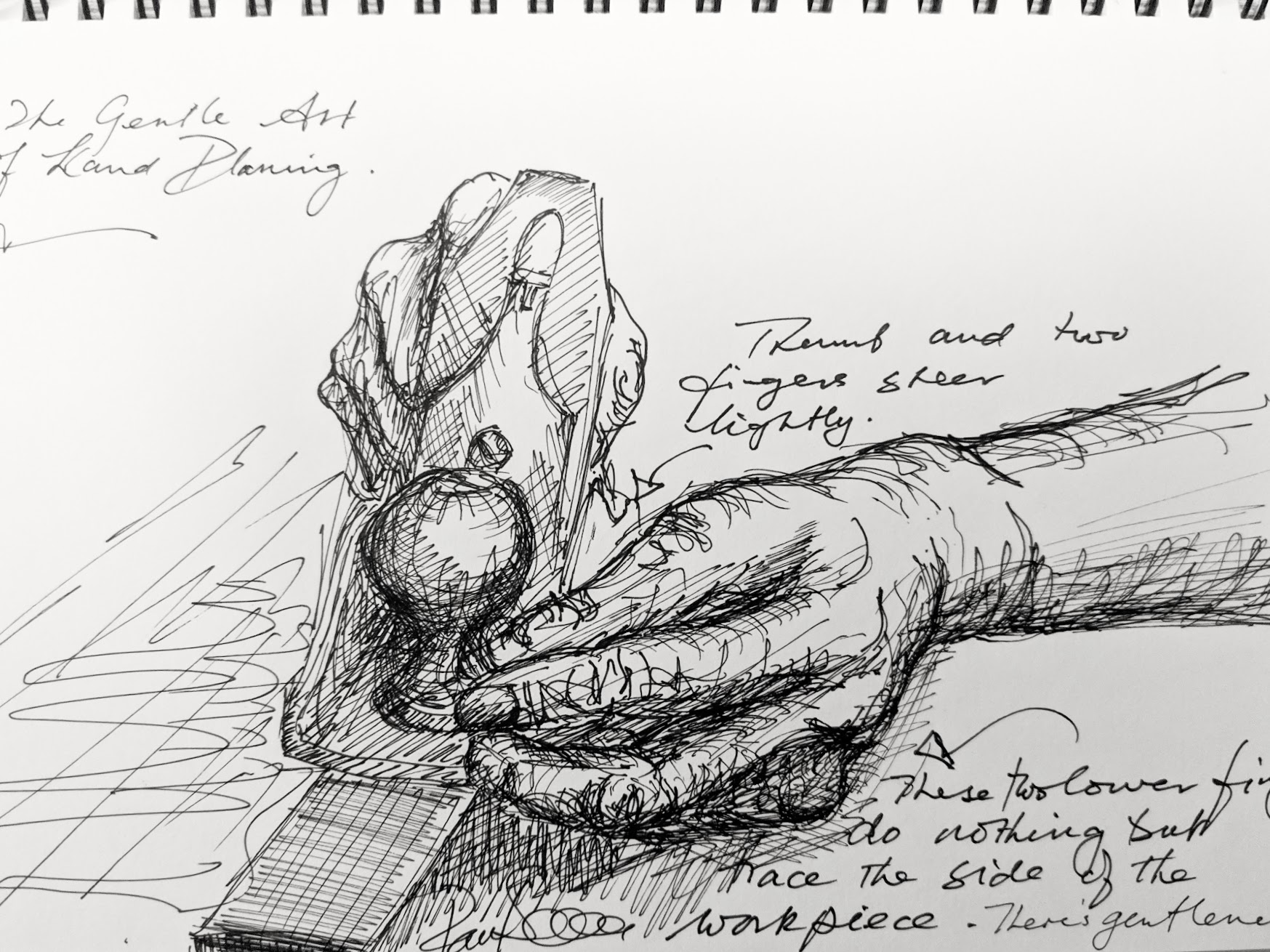

Returning to the real world at the bench with a box rim to reconcile or a sash window to level over in a quiet corner of the shed, you should consider rejecting the bulldog bearing down advice you’ve read of or watched in a video. Better to tell you the truth now. I watched a video of me going about my work the other day and I watched my hands change position a dozen times in the planing of that project. Rarely at all, if ever, did I have full fist grips on the fore knob or tote. My hands twisted and turned, lulled and shoved minute by minute as `i perfected the wood.

I made a video of the work in hand but here are some of the contortions I went through without my knowing I did such a thing. I replicated them as exactly as I could to help you understand that there is no one hand position fits all wood planing tasks. Here they are:

On a recent project I switched my material to Guanacaste after seeing gorgeously figured boards on the clearance rack… I was taken back by the sensitivity to grain direction and knots with the hand plane and hand router… I wonder why I’ve never seen a hand plane demo with Guanacaste?

The project came our great, and I learning to negociate the demands of this wood was a formative experience.

I have been working a lot of Guanacaste recently.. It’s a relatively common wood here where I live on the borderline between North and South America.

It is challenging wood to plane, with quite coarse fibres and areas of reversing grain, but has a beautiful lustre if you can tame it.

I am sure you are aware that if you machine it or sand it the dust is noxious.. It causes reactions from a peppery nose through to blotches and hives on the skin and breathing difficulty.. !

Just finished making two beech mallets based on your designs. Your blog comments about grain shifts made my day as shaping the heads was full of surprises, with abrupt grain twists and also nice spalted effects on some of the faces.

When I started this project, I thought the mallets would look blend, but I now have two -much more interesting – works of art full of character.

I’ve just ordered some yew, so the upcoming challenges won’t be a total surprise!

Great points Paul. This is like purchasing a musical instrument, the guy at the guitar store can make the worst guitar sound good to a novice. I think people have unrealistic expectations, and compare themselves to masters that have been doing this for 8+ hr a day and for decades; when they can’t do it as good after a few days or weeks, they get disappointed. So they are well conditioned to accept that it is the equipment, and not that they lack the feel in their hands. They don’t seem to grasp that feel can only be earned through real-hard work, this is how God set it up for us humans. Granted there are talented people who are just good w/ their hands, but they still have to work, just not nearly as hard as someone w/ average/below average hands to achieve the same level of feel.

Paul,

I would love to see the video about which you write. All of the changes and twists and pressing and lifting and caressing could be put to music I’m sure.

I recall decades ago when I was studying for a teaching degree, I was filmed giving a class about building science – I think the subject may have been acoustics and sound. When I watched the film afterwards I was somewhat aghast at the amount of pacing up and down, gesturing and arm-flapping I saw: I’d no idea that I had been doing it!!

I still catch myself doing it in design meetings with Clients, but I’m old enough now to stop being aghast, and now find it quite hilarious.

I second this. I’m looking forward to the video on navigating difficult grain.

Paul,

It seems the first and fith images are the same. Are we missing one?

Thanks, great insight, this. It’s a bit of tacit knowledge that is hard to convey I guess, unless specifically focused on. With what little experience I have I noted that I change my hand positions without thinking. Recently I do this explicitly to be aware of what I’m doing. I try to relax my grip more and put my arm straight behind the plane and not angled down a bit as is the first natural position it seems (or at least at my bench). Every little change affects the shaving in some way.

When I started woodworking not so long ago I sure did underestimated the intricacies that come with planing (and sawing and using the chisel and sharpening et cetera).

Thanks for all your teachings!

My mistake, took the extra out now. Thanks for letting me know, Mic.

You know, I hadn’t considered this, even though I know it to be true. I’ve watched some of those videos of one or another planing a piece of wood and have it come out perfect after touting how sharp they got the plane. I was dutifully impressed as it was meant to be. You hit this one right one, Paul.

Spent decades working with metal on many different machines and having taught others how to use those machines and all the little nuances that come with the process I can relate to your article on many levels. As you may be aware, different metals have different characteristics that require “different hand positions” so to speak.

I smiled a few times reading your words. I’ve been that fascinated little boy watching those videos of perfect planing techniques more than once. Thank you for pointing out something that I, like others I’m sure, either haven’t thought about in a while or weren’t aware of at all.

This is very helpful to read. I have been trying to learn the hand plane techniques. I bought a nice #4 from Lee Valley and that made a huge difference over my Home Depot junker, but it of course didn’t lead to perfect boards. I have been very hard on myself. I recently received a gift of some Wamara, and in making a bench I had tremendous difficulty with sudden unexpected tear out. It seems even with a very sharp iron to take a lot of pressure to move the oiled sole of my plane across the wood. And with that pressure it is hard to go slowly, and hard to know where it will tear until it is too late. I really want to know what are the next steps I need to take to get better. I try to pay attention with my eyes and feel with my finger tips, but I have a lot more intuitive sense with the router plane than I do with the hand plane for some reason. I think it is the amount of force I use. I remember listening to Paul talk about how to start a cross cut by softly rubbing and I think George told him go softer. Now I have really lightened up my saw touch things are going much better, but I can’t seem to lighten the hand plane and still make it go. Any thoughts on this topic would be appreciated.

Don’t believe all the self-appointed sales gurus tell you. Sometimes there is nothing you can do with a plane and you must always be ready to resort to the hand plane’s best friend the #80 cabinet scraper or the card scraper. There is no shame in that. Just get it as close as you can with the plane and finish off with the scraper.

Paul,

To your point, in addition to variances in wood, I find variances in plane performance between similarly numbered planes and at different times and with different woods. I have four number 4 Bailey/Stanleys. Three have original thin blades. One has a thick Hock blade. Two are corrugated. Yet, on a given day, each one might perform differently, from each other, from the same one one different wood. And this might result even though I sharpen all four at the same time. As you teach, you must confront the tool and the wood as you find them.

Your different hand positions are essential to how the tool performs in a given circumstance.

Thanks Paul.

My question is how much would Paul typically hand plane off a surface?

I’m making 5 of the keepsake boxes for my granddaughters out of cherry and starting with 3/4” stock. The plans call for 5/8” x 6” for the top / bottom and 9/16” x 4” for the sides / ends.

I had a 10” planer so that’s what I used so no problem this time.

How would Paul have approached this with hand tools? Would be have hand planed everything or hand saw the pieces thinner first?

I guess I’m wondering if there’s a max amount Paul would hand plane before he would try to saw the thickness down close first.

An eighth of an inch is not much to plane down for one box but five is more than hand planing so had I a planer I would probably use it too. I don’t have a problem with machines. What I have a problem with is wealthier countries or people thinking everyone has access to them or should aspire to them as some superior way to work wood. That said, I would be more likely to use my bandsaw and then hand plane the few strokes it takes to clean off the machine marks.I also always hand plane any and all surfaces left by machines because the surface is superior from hand planes.

Thanks for your reply….that really helps.

After closer inspection, I can actually see slight imperfections in the surface from my planer…. slight undulations or hesitation marks as the material was passing through. I’ve marked those pieces so they’ll be on the outside when I create the rounded surfaces.

At the point I’m at thus far in the learning curve using a hand plane, I know I can get that final surface better using my hand plane.

Really appreciate your teachings on this and other hand tools. Have gone from almost never using my hand plane to using it all the time without hesitation in a project!

As you said, I have rarely taken a full length shaving, but these guys do

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v3Ad6tBdLbM

But not in the everyday real world with real knots and fissures and such. Most people could enjoy a few hours fine tuning a plane and picking out perfect wood for the fun of it. It’s more in the nitty gritty of daily life I am trying to help others to see here. Not so much the fun stuff outside of working.

So which of these grips is the one for taking down knots in my laminated spruce work bench legs? LOL. Because I’ve got some humdingers that the plane is just riding up over.

In all seriousness, I realize that knots pose some serious issues when it comes to hand-planing. For a project such as mine, do you just accept them, work with them, and be happy with slight irregularities in relative surface squareness? I’ve already got some tear-out so what’s a little knottiness gonna hurt. 🙂

I think for a bench I would definitely live with it, but you can go with a very fine setting and resharpen for every knot.