Whats My Worth—Part III

In modern times we might refer to our self-employment as freelancing. It sounds better and seems to settle the matter for those we’re telling the outcome of our recently completed degree years to. Of course in certain spheres large companies force you to become ‘independent contractors’ so as not to have to employ you directly. Sub-contracting is common enough. Lump all the terms together and you still end up with a band aid on the problem. Giant conglomerates and not so giant ones, I think of Carrillion on the one one hand, and then Joe Bloggs round the corner who scuttles of like a roach before the full bill gets paid. Milking the world’s workers and leaving them hanging dry when they pull the plug on themselves to declare bankruptcy is not at all uncommon. In the USA this happened to me twice with companies like Gander Mountain ordering my work for sale in their outdoor super outlets. Two or three more here in the UK did the same. Beware the bigger orders. Especially when they pay you for a couple of years and then suddenly the payments are late.

In reality there are many freelancers without work in the same way there have always been the unemployed self employed. From free freelancer to subcontractor, and self employed to independent, It takes guts to be any one of them when you’re out there walking the streets in search of work. I think its sad that a culture can show disdain for those who go out to find work in what they’re passionate about rather than just taking any old job. Somehow it distances us from helping with the reality of our unemployed reality. Its interesting that Sir Walter Scott’s ‘Ivanhoe’ was the first time the word free and lancer was written evidence of the term freelance. It was directly attributed to fighting men who were indeed free lancers, those who would hire themselves out as a medieval mercenary to fight for whichever nation, group or person paid them the most. Today it still seems more associated with writers and journalists writing and photographing for magazines and media sources; freelancers actually do the same in that they will hire out to the more prestigious or high paying. But of course it does sound better to be a freelance this or that. You’re in work and working for the best, yourself. You determine who you sell to and for how much. Freelance as a term has crept into all areas of work life. Especially is this so with applicants for jobs if they recently graduated from University. The question to a ‘freelancer’,? “What freelance work have you undertaken since you left university?” Results often in your being told of work they actually did in the last year or two at university. Personally I would be asking, “how have you progressed in your quest to gain experience since leaving university?” “What have you made, written, practiced and so on?” Putting positive spin to impress is disingenuous. I’d rather help someone get a job they need and presents truth.

There never was anything wrong with being just plain self-employed. I first went self employed soon after my apprenticeship in 1973. In 1975 I took a full time job again that gave me steady pay and continued my self employment in woodworking. It worked.

Now to the question in hand and that is does hand made using hand tools command a higher price than say using machine methods to speed up the process?

I think that it is important to understand that machine methods indeed speed up the process of making. They lead to consistent levels of accurate replication and minimise the need for skilled input by hand work. Everything and I mean everything gets dialled in. The assumption that hand sewn is better than machine sewn is always in the eye of the beholder. Only the very wealthy are the buyers of hand stitched suits. It’s not too much different for truly hand made furniture.

The issue for me is when the machine dictates what you make according to their single axis, rotary cut. Inlay with a router is not really skilled work so much as easier work. Pouring resin laden with black toner and belt sanding it level is unskilled and not inlay. It stands in truths stead to say it’s inlay work. That doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be done, just that we shouldn’t believe all the signs that say, “Hand inlayed turquoise”. Now watch a skilled person make and inset string inlay sand shaded maple to form oysters or purfling, rosettes and binding unbought for musical instrument making, such like that, and you have art formed by human hand. That’s skilled work for which a well practiced maker can expect good pay.. Carving the scroll of a violin, now there you have more highly skilled and risky work.

There are things, some things, that machines cannot do or cannot do as efficiently as skilled hand work. Someone asked me how much they should sell my chairside table for should they make it by hand. I’m not sure that simple pieces like this are worth more if hand made so it would be right to sell it at the price of a machine-made piece. The difference of course is that the machine-made table takes three hours and the hand made one a day and a half. You cannot really charge more for two identical articles that look the same. Your hourly rate must include all overhead for the piece and then hidden costs such as property ownership, maintenance costs and much more. In my work hand making has made sense. I’m not batch producing so each step is individual. A customised piece designed for a specific opening demands the production of drawings, all the parts are sized as a one-off series, the work requires more direct input from start to finish. This is what my customer wants and this they must pay for. On the other hand I make a speculative design on a regular basis and my plans and design are all ready to go. It’s a familiar piece and I can work efficiently. A customer comes by, sees the piece, the price and buys it. Two completely different scenarios treated differently. So, back to my chairside table. I need to earn £1,000 a week to cover all things. I am generalising. Our circumstances are all different. Regardless. Divide my forty hours into 1000 and I come up with £25 per hour. By hand I can make only 3.33 tables a week. By machine I make 13.33 tables a week. To make the same money my hand mades must sell for around £300. For machine mades go for £75, a quarter the price for what looks like the same product. This may seem simplistic but complication with more formula will not make the example much different.

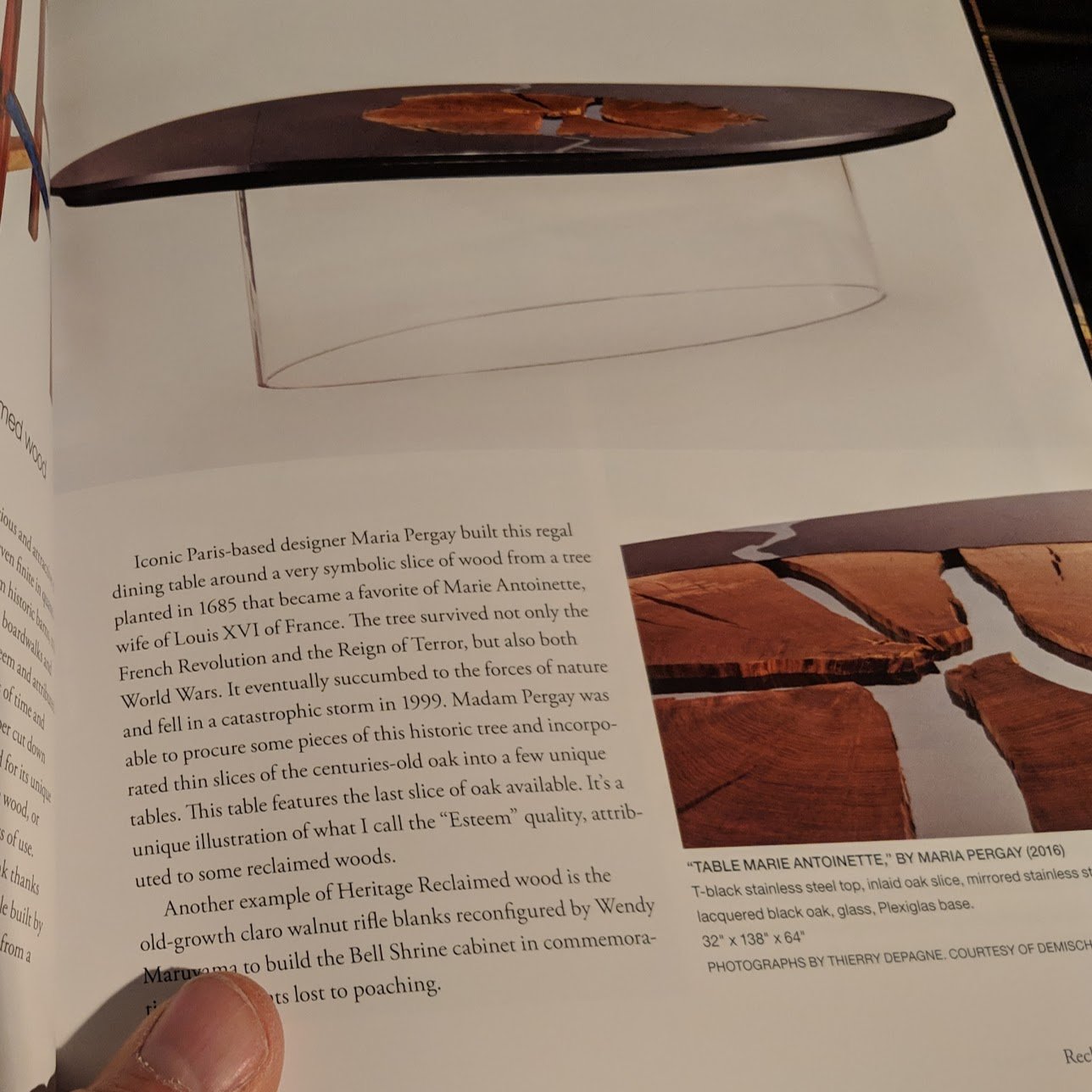

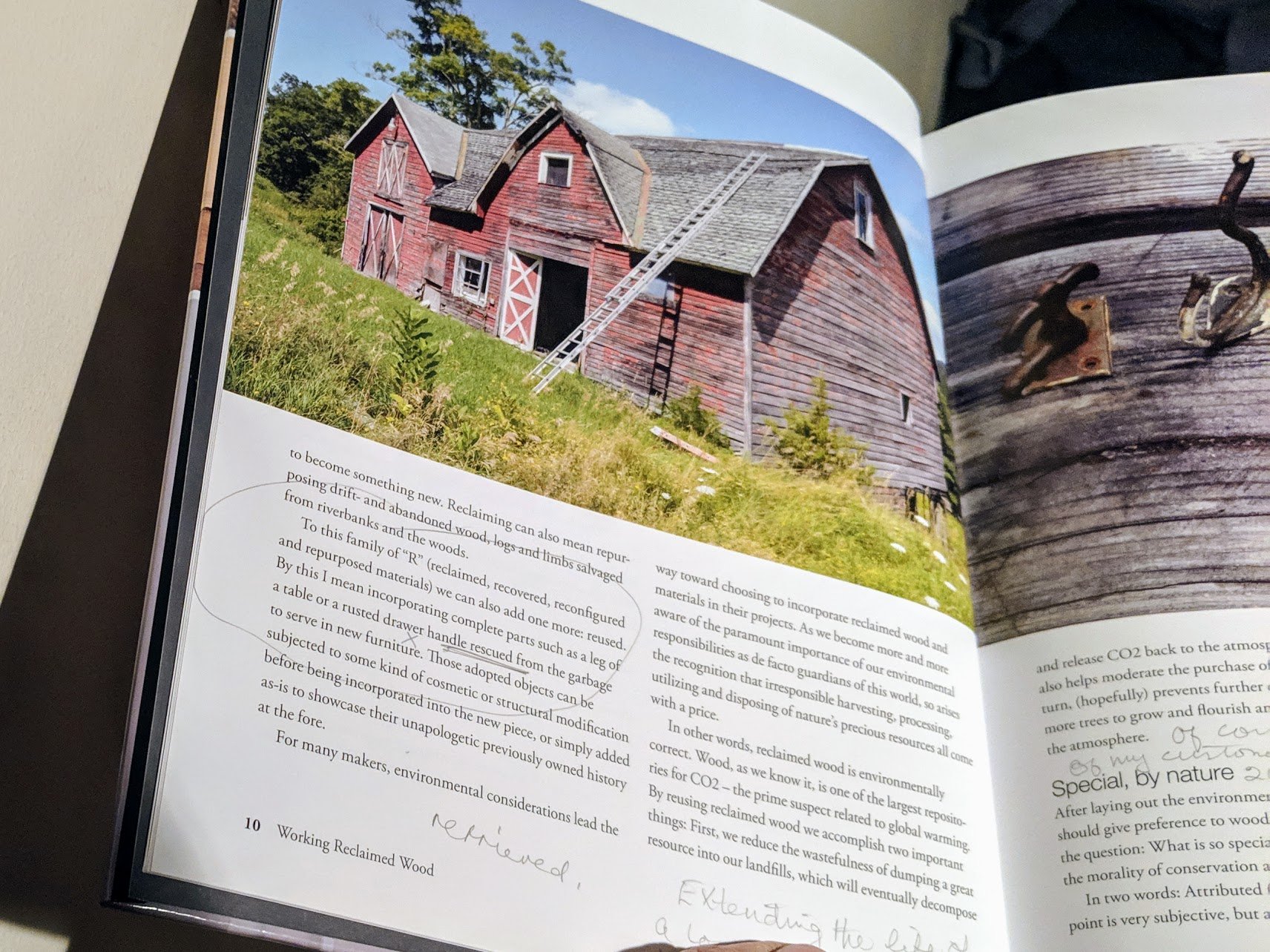

It’s from here that we must venture into the realms where woodworkers with independence and hand skills must rethink our ambitions. Hand skills are not always necessarily slower than machines. You must look at the work type. You might think that I have lost the plot here but bear with me. In the midst of the questions I get I receive Yoav Leberman’s book Working Reclaimed Wood; A guide for Woodworkers, Makers and Designers. Having found time to both read it and examine what’s said in it, it’s important to note that many furniture maker/designers may often well play a different tune by using their freelancing opportunities as more militant radicals to set the scene quite differently. Especially is this expanded when hand skills are considered important to the creative and freeing process of making. We can well carve out a future for our work with or without relying on working with reclaimed materials or any such thing. And I am in no way saying that we shouldn’t. Just that for some there will be a settledness about making conventional pieces, but that adding in some of what Yoav speaks of in his opening chapter real intrinsic aesthetics adds to the value in a variety of ways.

More to follow!

Thank you again for answering my question (questioner #2) in such a complete and profound way. Your answers have resulted in another question that only I can answer. What kind of woodworker do I want to be?

For many if not most of us who read Paul, the craft consists of one-off pieces made in our spare time as a pastime. For me at least, the answer is obvious: hand work makes more sense than machine work. What’s the rush? We rush all day at work and in our personal lives. Why rush the craft intended as a break from rushing?

Woodwork in the West mechanized for the very economic reasons Paul mentions: economies of scale to meet consumer demand for furniture. Makes much less sense on non-economies of scale (unless you just get a kick out of piddling with the machine tools.) I hated spending more time adjusting a machine than working wood. Not how I choose to spend my time.

Thanks again, for using your platform for reason. Cheers, Paul!

Paul, I was drawn to your piece and then saw ‘Gander Mountain’ as someone , or something, that had let you down, nothing to do with me but as a Gander, I’m sorry that someone bearing my name acted like that. But, to your writing’s core; I think you’ve hit the nail bang on the head. I’m a long-time DIY woodworker and perhaps because of that was willing to pay ‘over the odds’, as a friend said, for a dining table in our new/old house, but we now have a table that will be a family heirloom (complete with maker’s mark and our inscription) which will last, essentially, for almost ever (as long as it’s not in a house fire!), unlike the stuff from the High Street ( we were lucky enough to afford the piece) has been consigned to the recycle tip. And that’s it, we don’t have a ‘bit’ of furniture, we have a table made by a woodworker five villages away; it’s not a ‘thing’ it’s a ‘piece’ made by a craftswoman and it will continue, carrying our memories well into the future when our grandchildren will be old, and remember sitting round it at Christmas (and at other times!). Thank you for your inspirational writing.

I really love your simple definitions! I’ll be sub categorising the Bits from the Pieces in everything I look at now!It certainly addresses the mind on what approach to adopt when creating a piece of woodwork (“Am I making a bit or a piece?”) – I’m not being sarcastic either – I mean it)

Well crafted discussion. And not to challenge or be “contrary”. I have been a tool/machine user most of my life. And not of the highest calibre. Building, fixing for our own use.

After discovering Paul’s videos. I began building my hand tool inventory and skill. Inventory doing well, skill not so much. Still using power machines for the heavy work. Weak heart.

Thanks Paul for the encouragement and inspiration.

Steve

Thanks Paul. What a simply complex question. Many thoughts come to mind on both sides of the process of building/ selling and using and purchasing. I am a retired machinist of 45 years experience. I like machines. I appreciate their value. They have enabled me to make a good living for my family. Sorry I do not love them. I like them. When I retired I wanted to start real wood working. Got the usual powered equipment for my shop. I like the machines. Sorry I do not love them. By chance on Youtube, I started watching your videos. I love them. When I purchase an item the worth to me maybe not quite so much about the cost ( with in reason) but more about the fit, function and quality. In can sit in a fold up aluminum yard chair and eat my meal or in a well designed chair built by a craftsman that I plan to pass along to my children. From the point of consuming the meal…. both are identical. From the point of pride of ownership they vastly differ. I like the fold up chair for its portability. I love the cherry dining chair. I have the history of who and how the chair was crafted. When I admire the precision joints, feel the texture of the wood and the finish it adds value(worth) to me. The aluminum chair is shinny. The cherry chair has a luster. I like shinny. I love luster. 30 years ago I had a large hand plane. I could never get the results from the hunk of iron that I expected. Now I know the problems was really who the iron was being abused by. I have a number 4 Stanley I reworked following your videos. Also, I have a Lie Nielsen. Cost quite

far apart from one another. Worth… to me priceless for different reasons. When speaking of worth and price they do not always go hand in hand. I am glad I have no plans to make a living producing wood products. As you have stated previously the formula to price your will basically remain the same. My questions to the folks, asking the question of worth a truly handmade product might be… Is your potential market willing to pay the price you believe you product to be worth? What are your expectations for self employment? Do you expect the customer to be one time or is your product one that will inspire them to return for additional pieces? How will your work make them feel when they use it? Does it inspire pride of ownership? I have never shown my aluminum folding chair nor explained its construction.

My neighbor came by and wanted to see my new table saw. I wanted to show off and explain my Stanley hand plane. Worth. Does your product offer something unique that is not readily purchased? Is it custom? The word Custom always fetches greater dollars in the marketing scheme. I hope going into wood working as a business provides you the ability to earn a living and still enjoy the process of creating. I am glad its a path I do not have to journey but I do admire the folks that take it.

Whats my worth? What a simply complex question.

Sadly, I firmly believe that the general public would be unable to distinguish a hand-made piece from one that is machine-made. Most can tell the difference between properly constructed furniture and flat pack. But that’s about where it ends.

Many times I have sold chests of drawers and cabinets, the customer being blissfully unaware whether the drawers are of dovetailed construction, let alone whether the dovetails are sawn and chiselled or routed.

The vast majority of the utilitarian pieces from the 18th century can be adequately reproducesd with today’s machines, and it is only the higher end designs of Chippendale and his contemporaries which require skilled hand work. Possible a planed and scraped finish as opposed to a sanded one sets the hand work apart, but that’s about all.

These days, with more time on my hands, I only make pieces which would be impossible using machine methods alone. Purely for my own satisfaction, as I’m quite sure no-one else notices.

I do believe you are selling yourself short.

A cabinet maker with your experience should expect to earn £ 25.00 plus per hour working for someone else. When they add their overheads they would be charging in the region of £ 100 to 150 per hour, if not more. for your contribution.

This should I feel be what you should be aiming for, as a minimum, in pricing your work.

Now it may well be that market conditions will not bear that cost and you will need to adjust accordingly, but if that is the case then you should be looking at a different market.

I think that it is the case that self employed craftsmen of most trades feel intimidated by charging what they are actually worth.

You, sir, have a plethora of experience and a skill level which has taken years of practice to achieve.

I truly believe labour is, therefore, worth much much more.

I think that you miss my point. I am not talking about me and I did say “generally”. Personally I might charge £1,000 before I even start the design work. I charged £25 an hour back in the late 1980s, before I went to live in the USA. I had two years of orders waiting for me. Gaining a reputation meant I left hourly rates behind and charged for an overall design.My customers wanted custom designs and not competitive quotes. The y could not take my design and ask another crafting artisan to make it. I did not sell the design to them. I was giving a general consideration to those emerging crafting artisans. A new crafting artisan would likely find it hard to charge £25 an hour if he or she have yet to build up their skills, knowledge and speed. If you as a new guitar maker take 200 hours to make a guitar and an expert takes 60 hours for the same piece you cannot charge the same hourly rate and hope to get the work. skill does indeed raise the bar and the price per hour but ultimately I would want to get known for my designs and leave hourly rates behind, which is what I did for the last 25 years or more.

apologies for the misunderstanding

I do appreciate your tips and guidance – great blog