Garden Bench Finishes

For more information on finishes, see our beginner site Common Woodworking.

Finishes come in many different forms. The confusion is great and opinions based only on opinion and little more serve to make things worse. I’ll try not add only opinion but tell from my personal experiences. It might work.

Oils intended to soak into surface fibres are supposed to, as they seem always to say somewhere on the can, “penetrate deep into the wood to give maximum protection from harmful sunlight, harsh rains and wintry weather” or worse still, “Nourishes the wood.” Most usually don’t. Often they do little more than harden up on the surface. Many if not most finishes create layers of thin film to build up coats into a thicker overlaid surface treatment intended to work as a physical barrier that’s not unlike a physical plastic sheet basically sucking itself to the wood’s surface first and then each subsequent coat sucking itself to the previous coats. Of course all of this relies on some adhesion. Sand it too smooth and the finish often peels off more readily. I’m thinking polyurethane and varnish here, whether they have spar, yacht or any other prefix to the name. One completely water-based finish describes itself as an outdoor furniture oil when no oil as such is used in the manufacturing of the product. At least that’s not oil as we might know it where there is an oily substance resembling a barrier to water. Outdoor wood finishes then can indeed have such diversely different chemistry as far as ingredients go it is hard to decipher exactly what the product really is. It would be impossible to take all of the different types and say these provide us with a one size fits all finish. Often they cannot be described even as a particular finish type hence the common use of terms like ‘oil’, ‘varnish’, ‘finishing system’ and so on.

Danish oil, for instance, can be made by six different makers, six different ways and each with entirely different ingredients and they can all be called , well, Danish oil. Whereas on Wiki it might give you a definitive answer, it is also false to declare it as Danish oil because of its formulation. I say all of that to say there is no defined formulation to its composition. As a rough guide Danish oil is very generally a combination of tung oil and varnish with other solvents to aid curing through evaporation. Tung oil would be the major ingredient with varnish usually making up about one third. The fact that there is no such thing as Danish oil as an actual oil, that is it is not an oil produced in Denmark nor is it necessarily grown or sourced there. It is the same way Canola oil is not actually an oil from a canola plant or oil taken from the ground in Canola. Canola is simply a branded oil developed from rapeseed by Canadian developers and the the name partly tells the story. “Can” shortened from Canada, and “ola” from other vegetable oils makes up the made-up name.

Oils, so called, may have little to do with oil as such and will more likely be a mix of ingredients designed mostly to evaporate. As we all know oil, when spilled, remains oily. In general we are looking to apply a finish we can touch and recoat in a few hours and at least sit on by the following day. To achieve that, most finishes must have solvents that make them fluid enough to apply thinly and evenly and yet leave the product on the piece by gradual evaporation of those solvents that thin it for applying. The most efficient evaporatives are what are referred to as volatile organic compounds (VOCs). In normal room temperatures these compounds have a high vapour pressure which leaves the finish to cure to a touch-dry level rapidly. Because VOCs are harmful to the atmosphere we saw the introduction of finishes with low VOCs come to the market, mainly as water-based alternatives. Many oil finishes are a combination of chemicals and naturally occurring oils extracted for the purpose of creating wood finishes. Linseed oil, tung oil and many others have been popular through the centuries. Using some oils on their own and without the introduction of solvents will leave a natural barrier on furniture as a so-called finish. Often these natural products are not so durable and so manufacturers add other ingredients to skin the surface with greater durability. That is why some surfaces, though coated with finishes, like say Danish oil, actually feel like they have a plastic coat rather than a more natural oil feel.

Our minds tell us that an oil finish will be the better for outdoors because, well, “oil and water don’t mix.” Adding a little polyurethane increases the resistance to moisture absorption and especially is this so when the first coats have been applied. It’s what happens over the coming months that changes the game. In seeing how makers sell their products, and indeed YouTubers demonstrating their application methods, you can be forgiven for thinking the oil is indeed actually “penetrating deep, deep into the wood’s fibres“. You can also be forgiven for believing you are “nourishing the wood“. None of this is true at all. Wood does have some degree of absorbency but different woods have different densities and it is this that says how deep any oil finish might penetrate. Mostly you will be applying a surface treatment of zero nourishing value with extremely little surface penetration.

Many things affect the actual finish type applied, whether it is the actual wood type itself, the condition of the wood, maybe the prevailing weather for the area i.e. saltwater, salty sea air, pollution, wet and humid atmosphere and so much more. On the can the manufacturers usually start their application instructions with something like, “Ensure that the wood is dry and free from grease, oil, dust and wet’. For most people this is more an impossibility because most people don’t realise that some woods are naturally oily or greasy and rarely do they have the ability to probe the wood deeply enough to know just how wet the inside of the wood actually is. Wood is rarely consistently dry to the same level throughout each stick and stem of wood in a project.

Buy wood that has been stacked outside for even a few days and the wood will be wet inside. When wood is still fairly wet with say 18% moisture in the wood, exposure to heat and sunlight will cause the wood itself to express the moisture to the surface through the porosity of the wood with its millions of cells.

Before this happens, and we’ve applied our three coats of finish, any increase in temperature will adversely affect the finish to the point that it effectively parts off the skin of finish applied, often resulting in a separated coat. Also, generally, what any manufacturer gives out as a general guide for the user is very, very general and to the nearest of possibilities relating to that product. In my experience it has yet to become an exact science because conditions are so diverse surrounding the place of application, the skill levels of the user, the wood properties and condition, type etc. Applying some finishes to say oily woods or extremely hard and dense grained woods is often a sheer waste of time. The truth is you can only generally believe what it says on the can because it’s the diversity of conditions that dictates longevity of any applied finish. We are talking about outdoor conditions in which we plan to leave outside our outdoor furniture pieces. In most regions of the world they are either completely unpredictable, utterly extreme or both. As I have said, some woods, because of their containing natural oils or high levels of density have their own inbuilt resistance to any longterm reception of finishes.

Some finishes arrive in the can as a thick gel with instructions to either stir or not stir depending on the type of finish. Stimulation to some finishes by brush or roller causes what starts out as a gel to become more viscous and flowing. These thixotropic finishes are different to other varnishes or other oil-based or oily finishes. As I said, many oil finishes are a mixture of oils, resins and evaporative solvents. Older products like Spar varnish and others used to protect long term literally result in a series of coats that cover the surface as layers of skin. The solvents used to liquify the material for application evaporate over time and leave a hard and resilient skin. On a mast or spar, rounded in profile, this works really well as does the simple outer of a curved surface like a boat. Often there is no beginning and no end as the coat connects with a full revolution of wrap-around wet-edge-to-wet-edge painting whether brushed on or sprayed. Because it is seamless and there are no internal or external corners the finish will always last well. Here I am talking paddles, oars, spars, masts and other rounded parts and such. It is when you do get to a complexity of interconnecting parts as abutments that you face the reality that the skin applied stretches and or shrinks to cracking or separating points. The ‘pull‘ and ‘stretch‘, caused by the extremes of cold and heat, result in surface cracks and separation somewhere be that near the changes in direction or over a wide expanse where the surface skin fails to expand at the same rate or speed as the wood. Moisture enters any fissure, freezes or heats up and before too long the skin has parted from the body of wood or previous coats. The main reason we remove the corners by planing or sanding to a slight radius is not so much for personal comfort but more so to increase the likelihood of creating a continuous surface that ‘bends‘ around the corners to realise the desired continuous skin. Many of the older finishes and indeed many used today are solvent based and this generally means they have high VOCs. We have seen a public shift from various finishes with high VOCs to waterborne finishes that are easy to apply and clean up and are considered less harmful to the environment even though that may be questionable as we are now finding out with plastics. Many varnishes are made from a wide range of different ingredients. Some innocuous and some harmful.

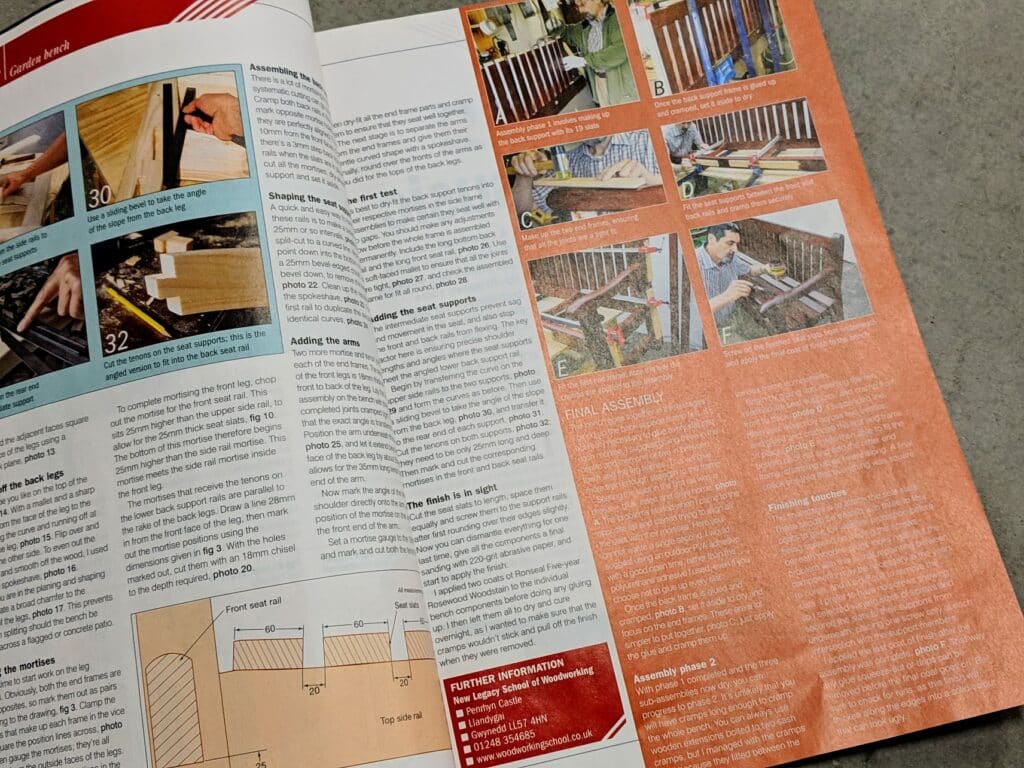

Many oils are supposedly safe. The question, as with many things, is do we really actually know? Stir it and it thins to a liquid. Usually they come as a surface skin brushed, sprayed or ragged over the wood to leave layered coats as a final protective finish. Though often espoused as long lasting and protective, most varnishes cannot literally seal off the inner wood from the harmful elements of weather over the long term and certainly there is no such thing as an indefinite finish. In reality the protective seal usually breaks down with the sun and weather and it almost always breaks down at any and all intersecting junctures around joints and the corners of the wood. To reseal is to allow the fluid to flow down or into the corners again and the reseal elongates the length of protection for another season. That’s at least the theory. My most successful record for a finish to date has been on an outdoor garden bench I made in 2010 for an article I wrote for a UK woodworking magazine in 2011. I used a waterbased product made by Ronseal called Ronseal ‘quick-drying’ Woodstain. Anyway, I’m about to recoat with the same varnish. Whereas I think it is true that we generally want to protect and preserve the inside wood for as long as possible to get maximum use for whatever outdoor piece we have made, I think it is equally true that we really like a smoother surface to sit on, rest on and keep clean that a varnish of some kind gives us.

Leaving wood with no finish on will result in a rough surface even when we wet the wood to raise the grain and then sand. Wood left with no finish containing inhibiting properties for ultra violet rays will ultimately lose all its natural colour. Makers of unfinished products use this as a marketing tool to say the wood will take on a natural silver grey colour over time. In reality it is not taking on any colour at all as it is an achromatic colour literally meaning it is a ‘colour without colour‘. It falls somewhere in between black, a non colour, and white, also a non colour.

I am not yet fully settled on what to use on my new garden bench. The pine pretty much has to be coated with some protective coat because of its lack of durability. Remember some woods, teak, and several others are almost completely rot resistant (which gives it a life expectancy in excess of 25 years intreated), woods like sapele and oak fall somewhere in the mid range so generally lasting around 15-25 depending on whether you take it indoors for some of the worst weather years or keep it covered periodically. Pine, without any protection and left out in all weathers will perhaps last only last 4-6 years. With finish you can expect longer life, I believe, but it will as said above depend on your determination to finish well and be prepared to recoat every five or so. I cannot guarantee this for all of the reasons given. Coating with oil will give you a couple of years of colour before the breakdown begins. It’s a matter of personal choice.

Varnishes can now be resin-based, chemical based or water-based. Oils are available but the reality is they are often unpredictably evaluated. You must remember that the longevity of finishes can be dependent on the wood type yet the wood type is rarely mentioned by paint and finish manufacturers. Some woods have a very short lifespan if left to the two most damaging elements. Wet wood succumbs to fungal attack, pure wet rot and a range of other degrading affects. Sealing wood can seal water out AND seal water in at the same time. Once a piece has been left outside for ten years the wood may well be saturated inside in areas you may not be able to find. Applying a coat of varnish without taking the piece inside for a few weeks or even months may well result in sealing water inside the fibre of the wood you are trying to protect. When the sun shines the wood shrinks or expands depending on the amount of moisture in the fibres. In a new build it is best to allow the wood to acclimate to its surroundings but not too much. A 10-11% moisture content will work well. Applying three coats of a reputable wood finish will work well before exposing it to the permanent outdoors if indeed you do want a finish. With waterborne finishes. I prefer to coat some parts before assembly because of awkward access. It is up to you whether you glue or use draw-bore pegs to keep the parts permanently together. I am of the view that glue, any glue, waterproof glue included, will hold in water, disallowing the release of water from the wood in most cases On my two benches I am going to rely on the draw-bore pins alone and no glue. I plan to finish the pine one with the Ronseal outdoor finish again. the oak one I will leave for a year and see how I feel then.

My concluding thought is this. We all want to believe in this or that finish as the best one or indeed our own concoctions that may well be as good or bad as a leading manufacturer. In the end it is only by trial that we discover what is best for own environment.

Paul, as ever, your blogs are fascinating and thank you for all that you bring to the woodworking community.

Rustin’s website claim that they were the first manufacturer of Danish Oil. Some 15 years or so ago, Ronnie Rustin spoke at the Southern Fellowship of Woodworkers (sfww.org.uk) and explained that it was meant to be called Scandinavian Oil, but there wasn’t enough space on the container for the full name, hence it was shortened to Danish Oil.

That’s interesting, but I first encountered Danish oil in the USA in 1984 so I think that this predates Rustin’s claim to famed introduction of Danish oil. It was sold everywhere I went in the USA so I think it certainly predated my first visit there before I went to live there in 1986.

Of course, thinking it through, as Danish oil is not an oil as I presented there, Rustins could of course concoct anything and call it Danish oil. Maybe I will mix a few liquids and put my name on it and call it Paul’s Danish Oil!!!!

Well there’s an oil I would buy!

The mystery of finishing is just that. Agree with everything except the gel stain being stirred to becoming MORE viscous and flowing. Viscosity is a strange term, a high viscosity liquid is like honey on a cold winter day (think highly resistant to move), while a low viscosity liquid is like water at room temperature. I think you meant to say LESS viscous.

Really enjoy reading about and watching your various activities and thoughts. Wish I had been able to visit you while you were in Texas.

Unless it is thixotropic – which many gels are ( fluidification of the material under (high) shear when flowing and stiffening at rest (or at low shear rates)) – custard powder or cornflour is a good example.

Not quite.

Thixotropic materials such as “thixotropic paint” are sheer thinning with properties as you describe. Dilatant materials are sheer thickening – like cornflour which thickens under sheer and liquefies when the sheer reduces.

Thanks Paul,

Overlooking the fact that a waterproof barrier prevents water getting in and out is often a problem you see in building work. A coat of PVA or waterproof paint may hide that unsightly mould in a damp corner of your home, but it will not make the water disappear. The water will just wick its way along further to where the waterproofing stops.

Equally and more seriously, a timber frame on an old house will not thank you for a coat of waterproof paint or cement if the entry point of excessive water into the frame is not treated. If anything, you’ll hold the water in and create a perfect damp environment for insects and rot which may otherwise be held at bay by simply letting the wood breath.

As with most things, companies try to sell a simple solution to problems with many factors. We improve by studying what’s happening, rather than reading tins.

As a novice woodworker I enjoyed reading about outdoor finishes. I wood similarly like to see Paul’s comments and opinions on finishes for indoor furniture.

Unfinished redwood is a very durable outdoor wood. I have a garden table of redwood that has been outside for 40 years in Michigan and is still quite sound, although the squirrels have chewed at the cracks where nuts & seeds were caught. The joints have no metal, so they won’t loosen over time from corrosion and ‘nail sickness’ of the wood. I’m pretty sure the table will outlast me.

Another preservation method is from Japan – sho sugi ban. Several years ago, I made a primitive garden bench from trashpicked Douglas fir plank and blowtorched it and wirebrushed it remove the soft tissue and harden the rest. I did apply a ‘Danish’ oil that is weathering out now, and I think that I might blowtorch and scrub it again and then leave it to weather.

The method of preservation by charring the surface was commonly used for fenceposts etc in Sweden “back in the day”, mostly for the part of the posts that were in the ground.

It was also “best practice” to put the wood up-side-down, as in the trees top end downwards, as it was supposed to lessen the woods absorption of water. (not sure this works, but the charring seems to work)

We used to preserve fenceposts and other ‘rough’ wood such as sheds, with Carbolineum, a product derived from tar. Worked very well, but has been discontinued for health & environmental reasons. There’s a replacement product now with the exact same name but it doesn’t compare to the true old Carbolineum.

I’ve spent many a childhood day brushing the stuff on. It was a nasty product, if you rubbed your eyes with your fingers it’d start burning your skin soon after. Also learned quickly to only apply it during overcast days, otherways combined with sunshine it’d burn your skin as well. Nasty stuff, but it did the job well. Fenceposts my parents installed in the mid-’70s are still fine. The fenceposts I installed over here about 5 years ago have rotted away already.

It wasn’t suited for finer stuff such as garden benches but perfect for preserving rougher woodwork. Back then it was also used a lot by the railway, to preserve wooden railroad ties.

Curious, is the “oil-based” more of a historical name? In the old days were they actually oil based? Or fatty acids, then slowly replaced by alkyds and other random chemicals? Or is it more to differentiate betwen “water-based” as far as paint brush cleanup.

Also, i have noticed old outdoor furniture as you mention(20+ years) where I reapply a finish and inevitably the joints swell or contract differently and break apart or crack. I am guessing because as you mention parts seal water and other parts can’t be reached.

Some years ago I made a replacement rudder blade for a Wayfarer Dinghy. It was made from two pieces of 18mm marine ply (BS1088 Lloyd’s approved) laminated and shaped. It was the deeper “racing” style blade which kept better (deeper) immersion when the boat heeled during sailing. In other words it kept a better grip in the water than the standard shaped blade. It was recommended to me that the blade (foil) should be epoxy coated first to keep the water out and then painted with single pack paint to protect the epoxy from UV. Any scrapes on the lower edge could be easily touched up if necessary. The rudder blade survived for three seasons (mostly sailed in seawater) until one day (on the Solent) and on a run with wind over tide (opposing forces) there was a bang and I lost all feel on the tiller. The blade had neatly snapped right on the line where the rudder stock finished! I could see the snapped off blade floating away just before the boat broached due to lack of steering.

The combination of epoxy and good quality paint seemed to be great at protecting the wood from water ingress but of course it did little to prevent the catastrophic failure.

A little while later I talked to the boat builder who made the Wayfarer dinghy and he said the reason the blade snapped was a combination of the boat surging whilst on the run, large tiller movements (ie the rudder blade at an oblique angle to the direction of travel and the plywood not having its laminations biased to resist the forces acting on it. He said that they fabricated their rudder blades from “anti-fracture ply”, a plywood specially made for them with the majority of the plies orientated in one direction! I suppose it was an accident waiting to happen.

I started writing a comment to this and gave up the direction I was taking as the topic is a minefield. As Paul has amply demonstrated there are a huge variety of factors which require consideration for choosing a finish. Having worked with and maintained a fair amount of variations of timber finishes which are all designed to help keep a timber appearance rather than cover it with an opaque finish all I can offer is what I prefer. I use organoil for exterior timber work . It is a penetrating type oil which is not intended to form a surface finish . It is simple to apply and reapply , preparation is straightforward and there are a number of pigmented colours which assist returning the timber to a reasonably freshly worked appearance. 6-12 months between coats, wash beforehand. I don’t like the skinning products , once they are damaged it all pretty much has to come off to achieve a decent finish, usually involving lots of sanding and a generous amount of toxic dust, even with vac attachments – hands up who likes that? I don’t think there is a holy grail as such, I do a lot of maintenance work , all finishes require maintenance, some take a lot less. Timber selection appropriate to the conditions the end item is exposed to is a good start. Being realistic about who will be maintaining it is another. Accepting the effects of exposure to the elements is another. I like the expression ageing gracefully rather than disgracefully. I think it applies quite nicely to this facet of working wood. Oh, irrespective of the product-follow the instructions!

Thanks Paul for this detailed article.

Not that long ago, I took some scrap cherry and walnut I had (two of my favorite woods to work with hand tools) and applied some home made finish (I’m a chemist). It was a 1:1 mixture of pure tung oil and mineral spirits. Over a month, I put on one coat a week. After the 4 coats, I cut the wood on a 45 degree angle because I wanted to see how much the finish penetrated. To my eye, there was no penetration at all; the finish was just on the surface. I was very surprised by this.

As kids we liked to dig with shovels in the back yard (nice sandy soil). At one point we buried a 5 foot long section of 1×6 or 1×12 old growth redwood. No reason, as kids we hurried lots of “treasures.” It sat buried in the soil for 30 years before my dad accidentally found it when planting something deeper in the garden. The wood still looked good as new after 30 years in the ground. Redwood is know to be rot resistant. To us and my dad, it really drove the point home.

So, is Ronseal the unnamed “outdoor furniture finish” used in the “How to build a workbench” project?

Hi Paul,

Thanks, again and again, for your sharing of knowledge.

My flat roofed contemporary home with many floor to ceiling glass windows/sliding doors was refinished 15-years ago with horizontal Western Red Cedar planks, not shingles. They wood has been treated probably 4 times with an oil-based treatment. The wood is now a very dark brown without any hint of silver coloration. The treatment did have something included to deal with the suns rays. The treatment was marketed as penetrating oil.

According to the product information it is now well past time for reapplication. Do you have any thoughts on what may be appropriate? Between the labor cost and the 20-25 gallons of treatment it is a very expensive project that from your comments on Danish Oil make it seem like it would be only partially successful.

Thanks,

Bob

That was a very informative article. I learned a lot in an area I knew very little of. Thanks

Thank you Paul for your very detailed opinion

Can I please add my “two penneth”?? Having earned a living painting blocks of flats….garden benches and gates (new and old)

I would not touch polyurethane varnish on exterior wood, I hate modern quick dry finishes ( just look at your picture showing it in action)..unless I am mistaken….it shows early drying from one small part to another….thick brush strokes.

A white spirit based product …requiring 16 hours between coats….allows for even spread, giving a profession finish.

Having read your very informative opinion and comments by others, the most important feature (unless I’m wrong) that has not been mentioned is

‘ microporous ‘ this feature allows wood finish to repel moisture at the same time allows wood to breath.

In the UK a product by HICKSONS has microporous properties….it comes with a very fluid BASE coat and on the tin says “gives protection against UV degradation”

I know that I could take that gate or 2 plank bench in your picture….scrub it with a green mould killer….allow to dry and give 1-2 coats of base coat and 2-3 coats finish Mahogany and it would look superb.

People fall into the trap of leaving this easily applied product for too long before further coats…….I was told by a paint rep that the last coat is sacrificial. Just leave for 1-2 years wipe off with white spirit and re-coat.

As for your bench I would give it one coat basecoat, rub off standing fibres when hardened and in an attempt to disguise pine grain …give a further base coat stain……then two coats finish…….mind you, you won’t be able to perch on it for a while

I would use a couple of number 12 galvanised screws on each leg bottom projecting 25mm to keep off the ground resting on a slab or brick.

Well that’s it from me?? Regards John2v

Can add that if applied properly and not left too long, all that is required to prepare prior to recoating is a rub with a ” scotchbright” pad and white spirit. If sandpaper is used resultant scratches would have be covered rather than a mist given with pads.

Some folk recommend a combination of Smiths Clear Penetrating Epoxy Sealer (a product designed for the marine industry) which protects against water penetration and Epifanes marine varnish which is supposed to be very UV resistant and hence protects against color changes and surface degradation. I have used the Smith product on a few things and it seems to work well. It also serves as a good primer for outdoor painting and varnishes. I have wooden external door frames that peeled every year. I treated them with Smiths and then painted and I am now on my third year with no problems at all. I tried this combinationof Smiths and Epifanes on a ceder table with moderate success. Unfortunately, the Epifanes began to crack and peal a bit on my cedar table after one season: as Paul’s article suggests, it cracked at corners and joints. But I will leave it to see whether the color holds, which is as big part of what the UV protection is supposed to be about. One last thing, I did very little to protect the legs of my cedar table and they are fine. It is the top, which gets pelted with rain and sun, that required the special attention.

Hi Sanford. Not sure if you are in UK….I think possibly not?

For a paint finish I know you will not beat the Sandtex Flexi system it has an oiled based primer undercoat and flexi topcoat.

It…as name says…….allows wood to flex, it is microporous so moisture can evaporate ……..I have used gallons of the stuff……now retired but my facia and soffits are still perfect after (can’t remember) at least 8 years

Hi Paul,

I use Le Tonkinois oil-varnish (sold at Dictum’s website but everywhere here in France). It’s a boat finish actually, and it’s fairly eco-friendly. Still you’ll need some mineral spirits to cleam your brushes and a bit of patience between each coat (a day!). I’m pleased with it anyway.

Regards

I’m sorry, Richard, but almost all of the oil-varnish are concocted with minor changes in the contents so that manufacturers can indeed put their brand on it. Varnishes mostly come out the same and I have no confidence that the minor differences between makers makes enough difference for me to say this is better than that.

Hi Paul,

great article as normal, thanks.

I am currently building a timber framed enclosed porch and I am going to clad the outside in larch. I purchased the larch from a small one man band with his own band saw saw mill out of Tain Scotland, he recommends using Osmo UV protection oil (German), which isn’t cheap, to help prevent the larch bleaching out in the sun over time. I was wondering if you had any thoughts on the product.

ps just purchase a 14″ lumberjack band saw and looking to more of your videos and blogs about the use of the band saw.

Paul

Hi Paul, I have used the internal Osmo wet area bench oil and found it to be an easy to use product which as to date matches up to the claims. Have not used the external oil but I am trying out their external oil based paint which in Western Australia will have a pretty tough run on a West facing timber clad face of my shed. So far , so good. A little goes a long way too, which helps to offset the cost.

Most warranties and guarantees are easy to give because unless the product fails soon after purchase most purchasers will have sold and moved on, lost their receipt, have no proof they actually applied that product to their cladding or garden bench and be unable to take the product coated article into the store for a refund based on technical testing. A ten year warranty payout for a failed product is seldom paid out because of these conditions, proofs etc. reading the small print is something most of us never do either. Just saying.

Understand what you are saying . Unless specifically asked by a customer to use a particular product I test them out in a limited sense on something of my own. I have had some products essentially fail in a little over six months. Others needing a lot of remedial work such as a lot of sanding before reapplying in twelve months. I would imagine that while there is some comparative conditions in most countries there are always particular swings toward high humidity, constant high levels of uv , damp etc in each respectively. Some products do fairly well in the Eastern parts of Australia, so far as I have been told and not all that well in the West, up North is something else entirely. I pay little attention to the claims of most manufacturers , a recommendation from a local tradesperson whom I trust and is older and thus had the benefit of longer experience is worth more.

Linseed oil seems to penetrate and soak into the wood, I have not cut open a piece of wood to check for myself though.

Is linseed oil not a good choice?

I have a garden bench, made of teak, that is at least 60 years old. It has lasted well partly because it’s teak and partly because I can put it under cover for the winter. However, a few years ago I noticed that the bottom of the legs, which are endgrain, were starting to go. I waited until it was really dry, having been inside for 6 months or so, turned it upside down and treated the ends with wood hardener and more wood hardener, and then more wood hardener. It soaked up a lot but it has worked. I have used this on other bits of outside wood too, though only on end grain obviously. As such it’s not really a finish, but it is very good at protecting endgrain.

This is a most fitting article, because the more woodwork I do these days the less satisfied I am with the available finishes on the market. I have always stuck to the oldies, as I know them best; Lacquer, shellac, varnish, some form of linseed oil and even waxes, bees or otherwise. The subject of finish is wide, deep and so very confusing – add to the fact the manufacturers are of almost no help what so ever! I have also discovered that a handful of manufacturers are buying up many companies lately, within a few years they will own most of the brands and trade names out there, lessening any kind of competition or variety on the market. The fact that most of these finishes have what are considered “trade secrets” so they are unwilling to divulge what are really in the products, makes this whole process of trying to research, buy and apply a product a nightmare. I have found most milk paint is not, quite a few are actually akin to latex and as a Danish friend told me a few years ago, “No, they do not squeeze oil from Danes to make that product” this whole area is confusing. I try as many products as possible but that can be extremely expensive, and find so many alike. Adding weather to this mess only makes it worse, as any piece of wood outside bears the brunt of all the elements, usually poorly. Best to gather as much advice and info from friends and experience, the makers and retailers seem to be little help and may actually sell more product by keeping us confused?! I do know that anything made to withstand weather, has some kind of solids whether plastics or others, to form a film much as you describe. Good luck, we all could certainly use more help in these matters. Sadly, you could devote two blogs to this subject, and wear yourself out in the process!

For what it’s worth, I can share a few experiences with near-natural finishing products.

swedish red paint – I used this on a shed for the kids in the garden and so far it has aged well. I bought the variant you have to cook by yourself (bit time-consuming) and it contains iron sulphate, linseed oil, pigments and grain starch. Also available in different colors.

oil paint – real oil paint, one without any drying agents; takes quite some time to apply multiple coats; used it on the shed trim and beams; for coloured, opaque objects

boat soup – from linseed oil, tung oil, pine tar and pigments; I used this on a larch shed front, wooden doors, patio floor and table; darkens the wood considerably and I can’t tell the long-term durability, yet, but I like it better than other varnishes which flake after some time.

I don’t think there is a good way to finish a wooden patio floor where soil, sand and dirt will abrade it, but I plan to reapply the boat soup once more this year.

milk paint – I assume you have to get branded goods like old fashioned milk paint if you want to be sure about what’s in it; I usually apply coats of oil or shellac on top; haven’t tried it for outdoors, yet.

natural oils – linseed, tung, walnut, hemp, without drying agents; it takes about a week to dry per coat so it’s a lengthy process; I use them on kitchen utensils, tables, bowls, tools; but also no outdoor expertise I could share.