Sharpen More Often

There is no prescription for how often a saw goes dull or how often you should need to sharpen this or that saw. Truth is for most of us, in reality, is that we are more likely to sharpen less often than too often. The reason for this is that tools still cut surprisingly well when they are surprisingly dull. Experience working with people learning has shown me just how far they fall short and how much they overwork an already dulled cutting edge to optimizer their worktime. Unfortunately, it’s quite common to think that it’s a choice they make and that they simply need to expend more of their own energy to expedite their work. What they don’t realise is that many things are sacrificed by their unwillingness to sharpen up.

Here’s the thing. Planing my oak this week I sharpened two planes half a dozen times. Once I sharpened one of my planes within five minutes of a previous sharpening. Planing woods like oak are not too demanding. Some times you plane an oak board 8″ widen and the shavings peel off like super long and continuous onion skins two feet long. The board feels like glass and, well, no matter how often you do this in a lifetime, it is still exhilarating; and so it should be. It speaks of having put all things into order, the sharpening, the adjustment, the choice of direction in planing and so on.

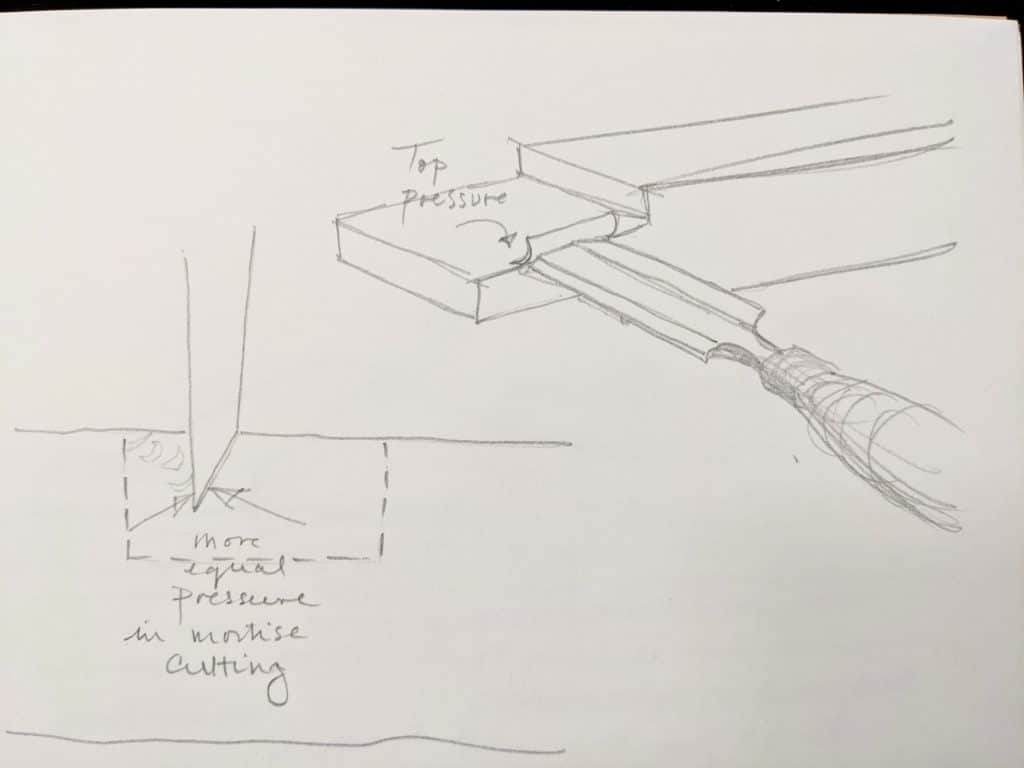

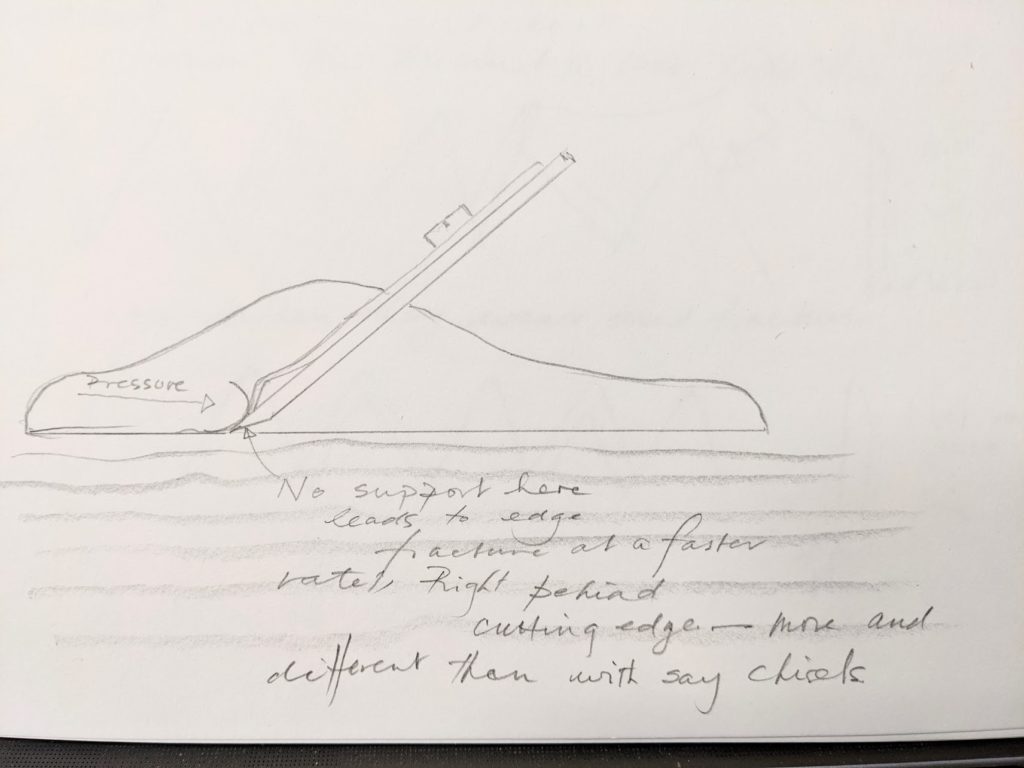

Even though I sharpen up very often, I am always conscious of how much the cutting edge dulls in planing. There is something in the planing action that is so very different than say chiseling, be that chop cutting or paring. In my view, planing dulls an edge far more quickly than chop cutting and paring. I believe it is something to do with the angle of presentation whereby the plane iron, at it’s fixed elevation of around 45-degrees, hits the wood with so very little back support directly behind the cutting edge but perpetually at the same angle every time in 90% of action except when a slight skew this way or that alters it. but then added to that there is a necessity to plane areas of wood that chisels might more rarely touch. Knots, difficult grain and so on. The plane generally makes successive passes a second or so apart and many times. On the other hand, perhaps 80% of chisel work is chopping and 20% is surface pare cutting. Either way, the chisel is usually approaching the wood very differently than the plane. Chopping is very near to 90-degrees, pare cutting across the grain sideways as in paring the face of a tenon from the side is again at 90% or slightly elevated a few degrees or so. When the chisel is presented to the wood there is often higher pressure to both sides of the cutting edge which equals out the pressure on the steel. So, in general, we must sharpen up regularly without prevarication or all too much reasoning if we want the surfaces to be in constant good order. These are just thoughts but good thoughts because when we see this we query less the need to sharpen our plane and get on with it. It is nothing for me to sharpen up ten times in a day and I don’t find it at all wearisome. Self-discipline is a positive thing.

In saws, there is a dynamic that happens we seldom consider in our early days working wood. We tend to think that a saw should stay sharp for months and indeed saws will often keep going for weeks and months depending oof course on how much usage they get. Here again, we tend to ask the question of how often should a saw need sharpening without considering the impact of materials on the saw and then too the work it will be used for. Woods high in silica will dull the saw and any cutting edge much more quickly. Woods with contrary growth rings of hard and then soft side by side can indeed be the very worst.

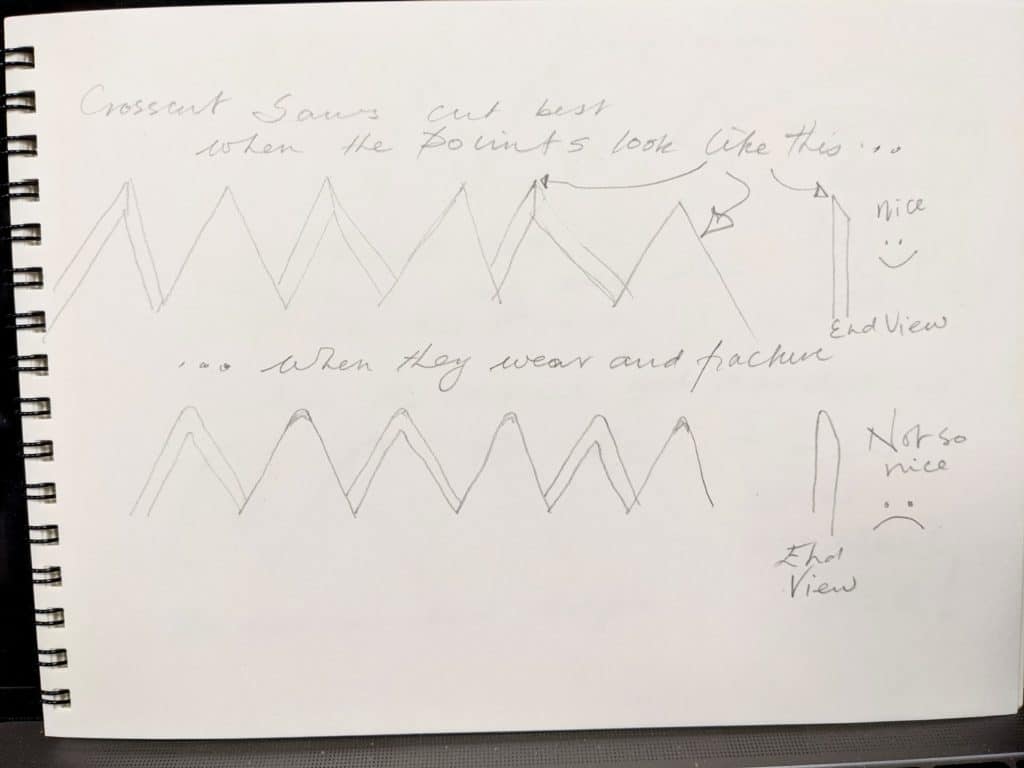

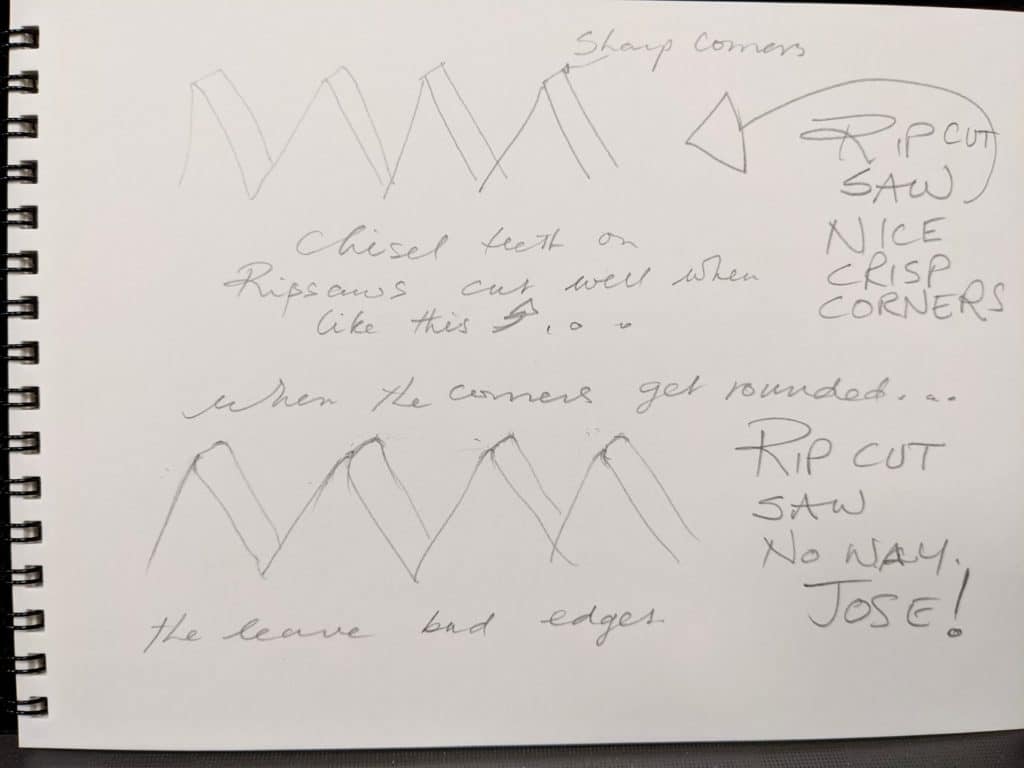

Some soft-grained woods seem to cling to the saw plate while other woods known for hardness and density seem to allow slicing like a hot knife through butter. There is no set answer for this but let me say yet again most if not all woodworkers tend to procrastinate when it comes to sharpening their saws and the reason is that they do not realise that the saw teeth do not wear as in water of a stone wearing but more a fracture and a fracture at particular points (no pun intended) The pinnacle points of crosscut teeth will not retain their sharpness as long as the wider chisel-points of a ripsaw teeth because, well, the very points themselves as so very fractious. These three-sided pinnacle points have very little to support them and it is the points that simply break off to a greater or lesser degree. And it needs only be a very small amount to make the saw less efficient. Both rip- and cross-cut saws need a regular touch up. A single half-length pass through the gullet of a saw strokes the surface and restores the cutting edges whichever the saw type. I use my rip tenon saw for the cheeks of tenons and then the gent’s saw for the shoulders. If I touch up both saws before the work begins, not only do I get the best surfaces and the crispest corners or shoulders, I am also less likely to need to do any remedial work of any substance. The knifewall and the freshly sharpened saw go hand in hand to perfect shoulder lines.

Regular sharpening during any project should be standard practice but not an obsessive-compulsive thing. Yes, I know there are those out there that just love to do that, but these are not the ones I am encouraging to sharpen. It’s seeing the need for sharpening on a regular basis without waiting until they don’t work well that’s so important and whereas it does make the work easier and more pleasant it’s more the result we want from the discipline. With saws, we tend to forget that it’s the sides of the plate that we are working on so that we get the shear-cut. If the corners of the teeth are worn, then the saw moves laterally away from the knifewall or cut line with each successive cut, making the shoulder-line or surface we are cutting rounded albeit on a small scale. This can lead to what looks like a shadow on the joint line

Great points (no pun intended!) and a great reminder! Well done article.

One aspect is also fear of wearing out tools and sharpening equipment if sharpening too often, and it will use up files and stones, but the time saved in the end is well worth that investment, I think.

Another one is the perceived waste of time. Especially for new woodworkers, sharpening takes often not only a minute or two, but a quarter hour or so. Again it’s not really valid, since the time “lost” will make subsequent sharpening go faster and then it will help work faster and also to a better quality or accuracy.

Paul,

A belated Happy Birthday to you.

I’ve seen you sharpen larger teeth like on panel saws and back saws but I’ve never seen you sharpen a fine toothed saw like a gents saw with 20+ tpi.

What size file do you use for these tiny teeth? I’m not sure I can see close enough to distinguish filed and unfiled teeth.

Thanks for your comments.

Bill Draper

In response to Bill Draper:

You can use what is called a “needle” file (still a triangular file) for small teeth. Here’s a rule of thumb I learned once – when the file rests in a gullet, the back side of the tooth should only come up about half way on one side of the file. That way, when you flip the file to another side, the file’s teeth are still sharp.

To distinguish between unfiled and filed teeth, use a sharpie marker to color the teeth before sharpening. Then as you sharpen, you’ll see the sharpie marks go away and you’ll know which teeth have been sharpened.

Thank you Bill, very kind. With regards to sight. If the saw is used sufficient to be dull then the gullet will be grey inside and so with each saw stroke the gullet will change colour from grey to bright steel. Use a Bahco 2-302-18-2-0 for the smaller teeth.

I learned my sharpening lesson making a 14″ x 20″ end grain cutting board of walnut and hard maple. Planed the end grain by make one pass rotate board 180 degrees make another pass then sharpen. It took a couple days of this to get the thing flat but in the end it wasn’t all that hard.

I probably need to sharpen saws more frequently and I still struggle with getting the right set on a saw but the more I mess up the better I get.

I do appreciate all of these good thoughts and sage advice.

Cheers,

Matt

As I’ve gained a little bit of experience over a few years, I’ve confirmed the importance of keeping sharp for all the reasons described. I’ve become pretty good at staying sharp with planes and chisels. I think this is because I have the most time invested with these tools compared to saws. With hand planes I find I’ve developed some intuition that tells me it is time to sharpen. I’m currently working on on a large set of built in bookcases which implies lots of shelves. Across a large project like this I’m able to experience how one shelf suddenly takes longer to get nice and flat and square because I put off sharpening too long. Across 36 shelves other factors tend to balance out and it sort of becomes clear that when the plan isn’t sharp it becomes harder to be fast and accurate with the outcome. I still have a lot of work to do with hand saws. Part of the challenge here is I’m simply not as good at sharpening these tools and this tends to make me push out the process (which ironically of course makes it even harder to get sharp again). When it comes to being obsessed with being sharp I think a lot of this has less to do with sharpening too often versus some feeling that there is a need to split atoms and have an absolutely perfect edge (which of course becomes imperfect almost immediately). I content myself with getting my plane irons and chisels very, very sharp with a quick session on diamond plates versus getting them very, very, very, very sharp with complicate guides, gear, setup, multiple bevel angles and similar. Sure, if I’m doing something special like the final smoothing pass on a really nice piece I shoot for very, very, very sharp. . . Seems to me there are diminishing returns on getting overly obsessive.

I agree that planes and saws seem to become dull much faster than chisels, which might also be the result of that long, long distance the cutting edge(s) travel over or through the materials they’re processing. When straightening boards with the plane i often feel on my fingers that the shavings actually heat op a little which tells me, that that good, old plane really works hard. And of course it all happens right on that microscopic edge of the blade. Thinking like that it’s no wonder to me, that its wears down quite rapidly. I don’t know how many meters a plane iron og the saw’s teeth travel through the wood on a productive day, but it’s quite – or surprisingly – many. So let’s sharpen…

I’m building my workbench and the construction grade lumber is really tough. The selections are horrible, but I got the best I could locate in 45 minutes of culling the racks. I have been stopping frequently during planing AND mortising to just make progress. At least if I don’t NEED to sharpen at that moment it will make the edge better.

I know in looking up wood characteristics on http://www.wood-database.com, i once saw that it mentions that doug fir has a blunting effect on cutters. And this made me realize why in the past it always seemed to be that my tools got dull faster on doug fir.

Also as far as chisels. Normally I tend to pick and choose where i am going to make joints on a board, so as to avoid knots or crazy grain etc. And I think this has an effect on why my chisels stay sharp longer than my planes.

Hi Paul,

Slightly off-topic,, but I have heard you mention the newer Spear & Jackson panel saw a number of times and how it’s a good all round saw for beginners, but that the handle could benefit from some reshaping (which i totally agree with).

I’d love to know if you have any videos on how to reshape such a handle so that it looks and feels nicer, and if not, do you plan on making one?

(Maybe it’ll give S&J the impetus to consider a re-shape in the manufacturing process itself)

Kind regards,

Thomas

Paul does have an older video where he reshapes a saw handle. I don’t have it handy. It came out nice from what I recall.

Sashimono apprentices, the Japanese art of building only with fittings, without glue or any mechanical fixation, spend their first semester of training exclusively on learning to sharpen their irons.

Hi Thomas,

Again I also don’t want to go off topic too far but I’m with you on your request for how best to reshape the modern S&J panel saws handles. I have quite small dainty hands and the as-supplied modern S&J handles are really too chunky and lack the finessed shape and very comfortable feel of the couple old traditional tenon saws I have. It seems to me that this is best done with the handle removed from the plate. Unfortunately the fixing of the handle to the plate is done via rivets (not screws/nuts) so it would be necessary to drill out the rivets. Thereafter replacement screws and nuts would need to be sourced to reattach the the handle to the plate.

I think this work would make an excellent “how to” video project as I am sure there have been thousands of new woodworkers who have purchased these value for money saws but could improve them by re-shaping the handle. I have bought three of these saws and have converted one of them from x-cut to rip. This was my first attempt at doing anything with saw teeth and I have to admit it took me the best part of a week (on and off in the evenings) using my newly purchased Bahco saw files before I was happy with the result. It takes some practice to get it right and that was following all of Paul’s advice. Once converted to rip cut I can see that maintaining its sharpness will be a bit easier than sharpening the other x-cut saws simply because there’s less critical filing angles to worry about and no need to file one, skip one before turning the plate around and working from the other side.

I’m sure Paul gets lots of suggestions/requests from people to do specific projects but I do feel this would be an excellent follow up project to Paul’s existing video’s relating to these modern S&J panel saws.

Thanks for replying. I’m in the exact same situation.

Would love for Paul to comment on it, if possible.

Interesting post, learned a few new things. Had never considered the difference in wear between chisels and plane-blades, but it makes sense when you think about it.

I postpone sharpening for too long simply because there’s a large fixed set-up time using the method I use, scary-sharp/sandpaper. Am slowly converting to using an old benchstone (no idea what particular type. It’s green and old.) but results are only acceptable, not nearly as good as with sandpaper. But much quicker than setting up my sandpaper rig. Past summer did a lot of woodworking without any possibility to sharpen, due to a move (I considered myself lucky to have 1 square foot of empy area for my feet to stand whilst working). It’s annoying to notice your tools are getting duller but not being able to remedy the situation. And no doubt by the time I start noticing dull-ness, they’re probably already pretty dull…

I’ve never had any issues with sharpening saws, that came very easy to me. Scissors the same. But planes and chisels… Perhaps diamond stones would help in bringing more joy to sharpening, but they’re not an option due to cost, besides being a tad overkill for a rank beginner as myself. Besides, if the older generations of woodworkers managed to sharpen with basic stones, then so should I be able to learn it that way. And so the struggle continues…

forgot to mention: the leather strop is the saving grace in my sharpenings. It turns a mediocre job in a tolerable end result.

@nemo: I was hesitating about diamond plates as well, because of the cost. Then I looked at Aliexpress and founs several suppliers that have diamond plates for just a few dollar each. they are approximately 170 x 75 mm and 1 mm thick. I took a gamble and have used them now for over 2 years and never regretted it.

I have a new video coming out soon on YouTube that should help you.

Mr. Sellers, that sounds very promising. I will be keeping an eye open for it.

Erik, thanks for the information, but it would be a last-resort solution for me, basically throwing in the towel and admitting to myself that I can’t sharpen the way as woodworkers in the past centuries did it, using exactly the same tools and sharpening stones as them. Hence, it’d be an admission of my own inadequacy. And please don’t consider that to be a negative judgment on anyone using diamonds. But for me it’d feel like cheating, that I chose the ‘spend $$’ route instead of investing time and effort and acquiring the skills required using the conventional stones that I already have and which were good enough for my father and grandfather.

Thanks, as ever, for the encouraging and useful posting.

Paul, when you sharpen your saws do you joint them every time? Do you set them every time?

No, jointing is only necessary to correct uneven heights of teeth but only then when it is particularly undulating or a series of teeth close together are broken off causing the saw to jar in each stroke taken. Setting too might be once every ten sharpenings, depending on how fierce or gentle the sharpenings have been. I think I tend to top (joint USA) the teeth fairly spaced out.

Thank you — very helpful.

Thanks Paul. I think the jointing and setting is where may become intimidated. If you watch videos on sharpening, every one does both the jointing and setting making a beginner like me think you must always do that. As such, I feel intimidated. Knowing jointing and setting happen infrequently makes me much more inclined to want to do it myself.

I have gotten quite comfortable sharpening chisels and plane blades. A saw, if anything should be easier.

I think we must recognise that many YouTubers create copied content only to make money and people think that having a youtube channel is because they are experts when you only need to watch for a minute or two to see that they are not. Many are mostly good and loquatious presenters who learned or copied from someone else the day before yet confident in their newfound knowledge to represent what they learned but have yet to master to an audience.

Paul, I’d like to think that you feel flattered that so much YouTube material springs from your material and experience. I see it so often. Funny though, that excepting you, there is not much out there on saw sharpening.

Sharpening is a funny thing, I love sharpening knives and plane blades and chisels, don’t mind doing router bits and planer blades, and yet despite spending most of my life woodworking for a living, at least half the time anyway. I have never got my head round saw sharpening, although I was very pleased with a rarely used tenon saw I did a couple of years ago ! I keep meaning to have a go on my Dad’s old Spear and Jacksons but never do somehow.

I’m afraid the speed of circular saws and jigsaws and the low cost of hardpoints has always stopped me, that is a work ethic from another era, remembering to take your saws home and spending an hour in the shed after dinner and remembering to take them back to work in the morning ( most bosses would kick up about sharpening saws on site during the working day).

Maybe now I’m nearly seventy I’ll have time when I stop work, ( whenever that is).

Having bought an tenon saw many years past it became blunt and I didn’t know how to sharpen (pre internet). it was put to one side only used to cut plaster board. All hail Paul sellers and UT video, heart in mouth I began, that cheap saw now is first to be used for those smaller cuts .

Now for the big saws.

Thank you Paul for your guidance and knowledge.