Tweaking life at the workbench

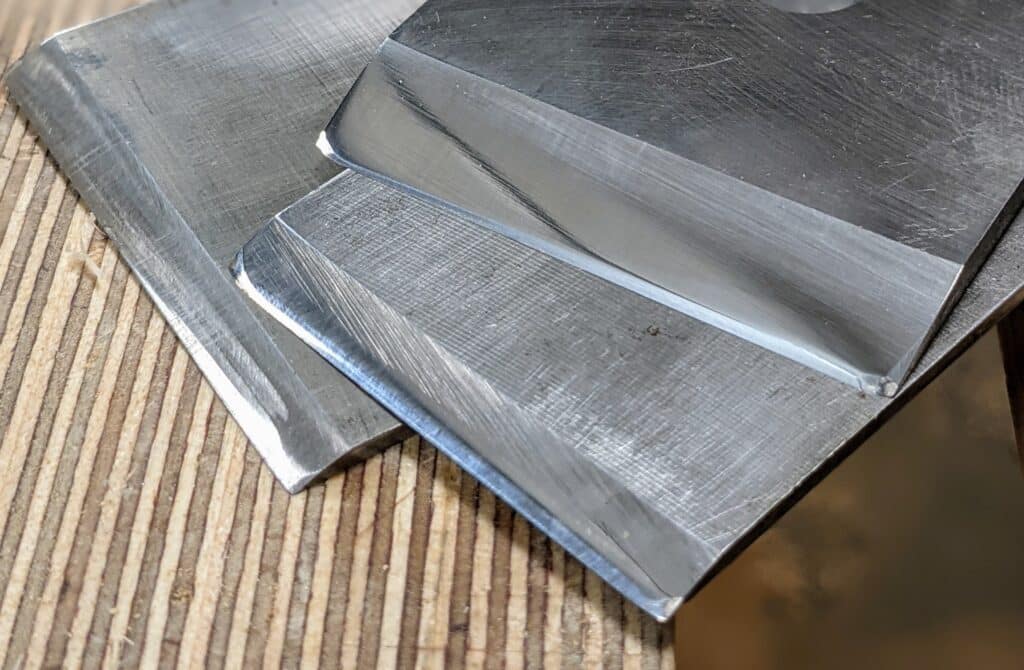

I plane wood flat most days. It’s inevitable and I enjoy it. And I use just a hand plane or two. I often work with two or three plane types I freshly sharpen before I begin. With my planes sharp first, I know I will be sharpening at least one of them within a very short time, that’s inevitable. What’s remarkable to me is the reality that nothing created in the last hundred years has really improved on this reality and that’s more likely in many centuries — cutting edges dull by use just as easily as they ever did. We may have more advanced steel types that give greater wear resistance and better edge retention, but that too comes at a cost. Harder steels make sharpening harder and longer to do. One way or the other, there is a compromise. Here at the workbench, where the real testing takes place on a day-to-day basis, nothing changes except that we become more discerning as to when we need to sharpen and hopefully we change our reluctant attitude to do it in just the right time too. Just as thick plane irons can take two to three times longer to sharpen, extra hard cutting irons do the same, and especially is this so if you choose no mechanical methods to do it. I do use a grinding wheel for grinding bevels once in a rare while, but 98% of my bevel work is just hand pressure on diamond plates.

I always aim to resharpen again before the cutting edge dulls too much so time-wise it’s not so very long between sharpenings. I cannot possibly say how long it will be before I ‘feel’ the need to sharpen up but I have learned through experience what is just the right time to do it. I am often asked how long it is before I sharpen my plane again as though it’s a distance and time-led thing — a bit like it’s an mpg (miles per gallon) thing, but in feet or metres squared and calculable. In other words, a 1″ x 6″ board two feet long would be roughly one square foot per wide face and with edges and end grain that might be somewhere around 2.5 sq ft of surface planing. I think that some might think it would be great to get out the app and punch in 2.5/ft/oak/english and see how many boards could be planed or how long it would take to do such a task and then how many miles before I need to resharpen. I digress.

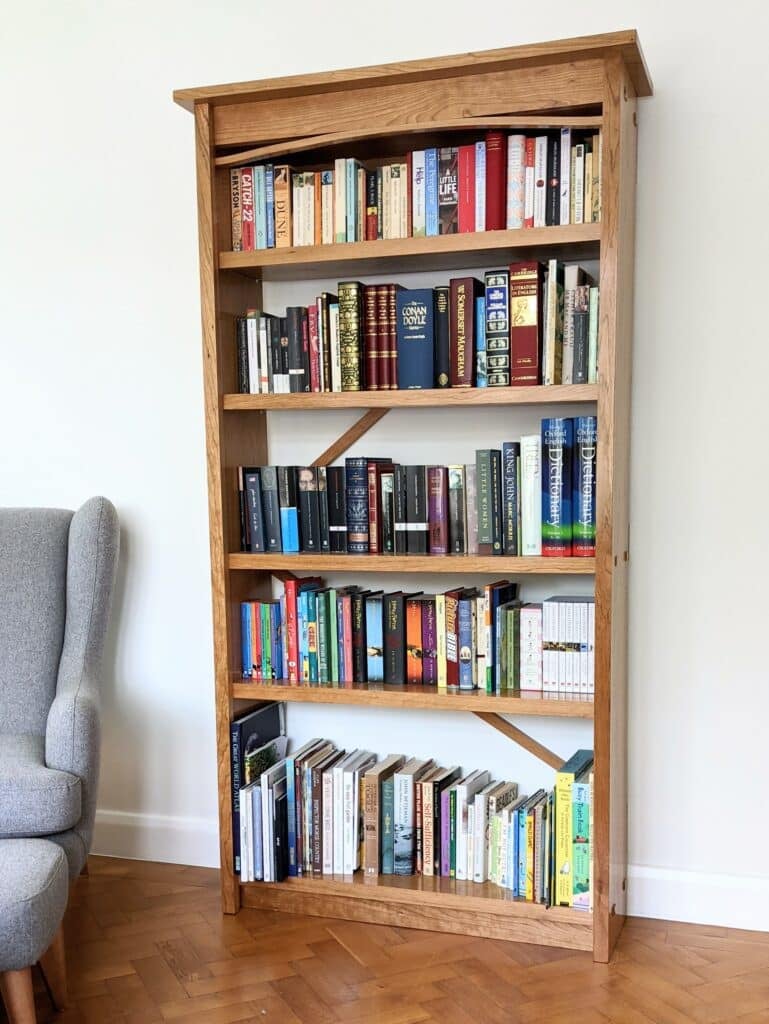

The bookcase I made below in cherry with seven shelves plus a spare, two sides and many other bits, might total 100 square feet. It would be handy if I could divide that hundred square feet by a set amount to calculate my miles per inch surface area and say I will need to sharpen up nine times to true-up and smooth and size all of the components to complete the job. Where I hit the bumps and forks in the road is that no two pieces of wood, even within the species and even in the same board, will wear down the cutting edge of my plane irons at the same rate. This, I am confident, is invariably incalculable, thank goodness!

So I say to myself, wood is just like life, it comes with knots in it. Knots, silica in the grain, wiry, awkward grain patterns to contend with minute on minute, all take their toll. Even with the best cryogenics in the world, and thick, cryogenic irons offer no real benefit over a standard blade*, a single knot in many if not most wood types, including most softwoods, can take out any fresh sharpening in a heartbeat . . . and I mean even a single pass! Compare hand planing teak to cherry and teak will dull your plane irons 4 times faster, even if it has no knots to contend with.

So asking me how often you should sharpen your plane is the same as asking how long is a piece of string? It takes what it takes. When I used machines to level and true my wood I was less concerned about such things. I used high-speed steel cutters in my planers and they held up for weeks at a time with no problem. Pass a board over a jointer bed and then into the open jaws of such machines and the twist was gone in two passes because, well, that’s what planers do well and do deeply. A single-pass can take out an eighth of an inch of twist and two passes a quarter-inch no problem. The same operation with hand planes, depending on the board width and length, could be half an hour’s work easy. Since I stopped using what industry uses a few years ago, I have been far more considerate and judicious in my working. My reasons for not resorting back to power planers? Shop space, health and safety, dust and mess and the fact that most amateur woodworkers around the world cannot (for a dozen reasons) own or use such power equipment. I use what they can use and get hold of and I don’t want anyone to think a shopful of machines with the necessary dedicated floor space is at all necessary to be a good and functioning woodworker. I have personally proven more than any other that they are not — we’ve produced many dozens of beautiful pieces, large and small, ranging from dining tables to baby cots and large cupboards. Oh, and then of course, there is the physical exercise I favour in my woodworking too. I see no reason to push boards into a machine and then go to a very boring gym to get the exercise I need throughout the day. Think two birds one stone!

I hand planed many square feet of oak for my prototype TV unit over the last few days. This includes an experiment using 10″ wide, 36″ long veneers of 1/8″ thick oak stock for laminating. I ended up abandoning this thought because of the time consumed in doing it and it is quite a trick to do with hand planes anyway. What I have come to notice over this decade of hand planing almost every stick and stem I have used, is just how much wood moves to points of distortion. Even when you go to great lengths to get the moisture levels in the wood down to a perfectly matched level to the surrounding atmosphere, wood will usually move to some degree. What was true and trued one day can be different the next. Leave it a week and it could be back to true again or it could be worse still. This is wood at the workbench and not the discussion in the textbook although they give insights too, of course.

In circumstances like this, a sharp hand plane is critically essential with a double emphasis on its essentiality. In my understanding of people as a whole, procrastination is almost always the issue in just about everything we do. Bins overflow, apologies come too late and dishes fill the draining board to toppling levels. It’s funny how we will push that plane to its absolute limit of our laziness rather than pop that lever cap, take out the plane iron and reestablish a sharp cutting edge. We humans will beat that wood and our bodies into submission with a dull cutting iron for an hour before we will take it out and sharpen it, yet when we do what we were supposed to do an hour ago we feel blissfully happy until we do the same again. My oak sections, boards and panels did move even after my curing of wood was down to around 7% and acclimatised to and by the surrounding atmosphere of my garage workshop by airconditioning to equal perfection. How can this be? The books all say blah, blah, blah! Well, it’s wood. It moves, it changes its mood and its mind and its memory! Wood is not always compliant and neither is it always predictable.

I remember when MDF came into being and how magazines of the age extolled its virtues as the new wood that could be nailed, screwed, stained and made to look like any wood you wanted it to look like. 50 years on we have firmly established its limitations. We no longer make chair rails from it and thankfully we never made ladder rungs from it, but some entities did come close. What MDF offers the industry of woodworking is stability. In general, whatever you cut MDF to stays. Unlike wood, expansion and contraction doesn’t happen to any discernible level. Inert to the level that it is, it usually works perfectly as a substrate for facing with veneers of all kinds including wood, plastic and fabrics. IKEA loves the stuff as do most furniture industry giants making tabletops and desks and case goods. For me, the stuff is as soulless as it gets. As hand toolists, we seek that which has proven longevity and we choose what can be best worked with our hand tools because we value the efforts of our physical and creative input. MDF, chipboards, pressed fibreboard and such, were designed for mass-making of all kinds using mass-making methods and equipment and then with little concern for longevity beyond the one-year warranties given. In that world we want product to become obsolete by design and by build quality. Built-in obsolescence is not just by wear alone but by fashion outmode too. In my world, MDF has no place at all. So I must resign myself to the reality that my wood will almost always move, even when I have done all to reduce that likelihood and, indeed, to allow for it. I resign myself to the reality that I will need to occasionally tweak it as I work it and that people will occasionally do stupid things with water after they have bought it from me. I know too that I might just get blamed for some distortion and even cracking when they place a table end grain up against a primary source of home heating such as radiators in winter.

Conclusion: Be prepared. Sharpen up more regularly than you want to, perhaps twice as much. Allow time for acclimation. Recheck yourself by casting your eye along a corner to see if what you had yesterday, last week or last month is still as good. Be ready to tweak things, especially your attitude and unbelief that this or that happened when you only turned your back for a minute.

*Retrofitting your plane with a Cryogenic cutting iron is simply a matter of choice and not an essential or even a necessity. These cutting irons cost twice the price of buying a complete secondhand Stanley plane on eBay, so up to four times that of a replacement iron provided new by Stanley. At £40 a pop for the new retrofit cryogenic version, plus shipping and handling, it’s not a low-cost upgrade and the advantage if any is at best negligable. The standard Stanley is just under 2mm thick and the ones being offered at 3.5mm simply mean you must spend about two to three times the time sharpening them. What difference does this make with regards to functionality? Well, none, really! A sharp iron is a sharp iron. The boast of longevity of a cutting edge is there but it is more fractional and not anywhere near say twice as long; I’d guess maybe 20%, extra, but of course, it is unmeasurable in the actual zone of woodworking, really. But whatever gain you have there is quickly lost in the extra time the hardness and extra thickness the iron takes to sharpen it. Effectively, you’re better off staying with the regular iron your plane came with. You must also watch out for the hidden salesmen who tout plane chatter as the result of using standard thinner irons. That is simply untrue.

I often have trouble to keep all parts square when doing a project. My schedule only allows for an hour or two of continues work. This means that the board that was square the week before isn’t anymore, and I guess it never will be. It would be great if you could show us how you tweak a warped board before beginning the joinery phase.

A lot depends on the type of wood used. Some will warp, twist, bend, bow like a coiled spring after being milled. What I usually do is cut to rough dimensions then let the pieces set for a few days to a week. This gives the boards time to release tension in the fibers before milling to final size.

Oh Albin, you keep all your parts square, I do ever so envy you. If ever you need cheering up during our present time, just ask for a photo of my “square” or my “tight” fit with “crisp” lines. It will keep you laughing for days. 🙂 I wish I could gift you my spare hours, nay days so you could enjoy more of your fun time.

I wish you well with your project. 👍

I think I’ve finally learned the lesson on sharpening. Recently, I prepared a scrap slab of white oak – you know, the D shaped ones one discard when making lumber from timber – into a garden bench seat, live edge and all. After removing the bark with an axe, I used a spokeshave (I do not own a draw knife, nor do I have much use for one) to clean the surface and make it somewhat uniform and smooth.

As soon as I felt the edge going dull on me, I popped the blade and honed it on the strop. 30 seconds to a minute at most, and I was back to work. I did this perhaps 2 or 3 times per hour. The difference in performance? Dramatic! I could just let the spokeshave glide over the surface, and it cut whisper thin shavings that left the surface pristine. As soon as the blade got dull, it started “chattering” – skidding and a jagged motion with a bad texture finish as a result.

Having my sharpening station set up on a support table makes the honing and sharpening bit a breeze. Love it!

I learned the hard way with the thick plane irons, they just took too long to sharpen. I also found it much more difficult to create and break off the wire edge. I switched back to the original irons and gave the thick irons away. My top of the line chisels took awhile to get to the “good steel” the edges kept fracturing until I wore them down, very frustrating process especially when your learning to sharpen. It was something called carburization during the heat treating process I was to find out later.

Having said all that I have found that the regular steels are more predictable today. I have some very old chisels that vary in hardness from one chisel to another which surprised me at the time.

I love the smooth mirror finish produced by hand grinding and stropping on leathers with two grades of polishing wax. But I also use a grinding wheel occasionally when re-shaping the cutting profile. The big danger of burning the edge and drawing the temper is always there. I combat this by very light pressure. I find that aluminium oxide wheels are cooler-cutting than the more common silicon carbide type. A spot of car engine oil on the steel will coat the outer surfaces of the cutting wheel grains and keep the steel cooler. It sticks to the steel better than water. Overheating is unlikely with all these precautions. But if it should occur, the oil will smoke, giving a warning. That is more than you will get when dipping in water as the cooling fluid. I suppose high speed steel is much less susceptible to damage from overheating, but agree that it’s too dear for many of us.

Great tip about the oil, Andrew. Might have to try that someday soon. I bought a so-called supersteel knife made by a famous Italian knifemaker, yadda yadda. More curiosity than anything and being gullible to sales pitches I guess. I can’t sharpen it for a darn. It makes a great paperweight though.

Jeff D: See Paul’s video on You tube, where he takes an old butter knife and sharpens it to produce transparent slices of an apple using a set of his diamond paddles. Here it is: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bailuQUh2mY

I work in my city forest with axes, a slick, chisels and a buck saw. Timber frame stuff, mostly. I see a lot more sharpening in my future when I transition back to fussier work with the smaller pieces I have drying in my apt. I’m 63 and going strong and I enjoy the rough work. I like a smooth, perfect surface as much as the next guy but it seems less important when dealing with whole trees that would rot unused unless I harvest them.

That sounds like brilliant work Thomas, good for you!

I have a novice question. I have been woodworking for many years but something has stumped me. How do you setup your platform on your bench grinder to 25 or 30 degs with accuracy and repeatability? Of course I would never use a coarse 36 grit wheel to sharpen, but I prefer the old Stanley/Bailey planes. Many of them I have are so faceted a jewelry store would be impressed. I am asking how to get the angle reset to the appropriate bevel then take it to my stones. If you have a video or blog on this already please let me know.

Thank you in advance

I don’t use wheels. I use hand files. But I have seen others use protractor and angle fingers to set up the platform on their grinding for this task.

I recently “reground” a 1 1/2″ framing chisel using a cheap diamond plate and a honing guide to remove a multitude of different “bevels”. took about a 1000 strokes, not quick, I did it as a sort of experiment. You could make yourself a wooden adjustable guide for your grinder. But course sandpaper on a flat plate and a honing guide will quickly regrind a plane blade. I think Paul has a video of this.

It is actually rather simple. I’d recommend cutting the desired angle on a stick of wood, not too thick or wide. Place it flat on the platform and adjust until you have the angle correct-ish. The wheel should ideally touch in the middle of the bevel, but it is not critical: ()\.

Set this angle at 25 degrees. Any flat piece of steel you place on the platform and advance into the wheel, will be grind at 30 degrees – be it a chisel, a three foot flat bar or what have you.

To aid in getting the bevel square, just color the tip of it with a sharpie, then place the square across and make a line in the sharpie with a screw or something, a few mm from the edge. Don’t grind to the line, use it as reference. Hold the blade like you would hold a turning tool on the lathe, one finger up against the platform to guide you when traversing the blade from side to side. Remember to cool the iron thoroughly during the process.

Create the secondary 30 degree bevel on diamond plates or stones.

A small correction: if you set the platform in accordance with a 25 degree reference, anything placed flat on the platform will be ground at 25 degrees (not 30). 🙂

And as Adam says: the angle is really not important. You create the 30 degrees on the diamond plates. And as Paul, I highly recommend diamond plates! I have used water stones and a Tormek knock-off in the past. Although they do work very well they are no match for diamond plates.

As for free-handed sharpening. I absolutely agree with Paul that one should train to learn to sharpen free-handed. However, I myself find it very difficult to maintain a consistent angle. I am getting better at it, but for now I go freehand on the strop only and use a honing guide when ever I use the diamond plates. I have started doing minor maintenance on the finest plate then the strop, when just stropping isn’t sufficient to get a good edge.

I have to find a balance between learning free-handed sharpening and getting a good edge so that I can work. This is a bit like dipping the toe in the water first, but perhaps it could help a bit on a task that otherwise can feel a bit daunting at first.

I’ll get there in the end, but for now I do use walking sticks from time to time. 🙂

If you’re ginding, I guess you’re essentially creating a brand new bevel and, as such, would be removing all the facets. Therefore, I don’t think it really matters about the accuracy and repeatability of setting the angle. 30, 32, 38, 35… whatever… it won’t matter.

I personally find sharpening to be a cathartic as the woodworking itself. Producing a sharp edge and using that edge to make another thing. It keeps me in the shop, all of it does.

I’ve only had trouble with chatter twice, both times the planes were Record, but I doubt the brand really had much to do with the trouble. The plane, a No. 5, had problems with chatter getting the blade square in the mouth. Close inspection by eye and touch discovered a small spur on the bed for the frog that prevented it from sitting firmly or square. A small fine file and less than 30 seconds and the plane is fine. The second plane was a No. 10 Carriage makers rabbet (rebate) plane. The plane would plane very thin shaving without trouble other than an odd singing tone. But the cut could not be deepened without the plane jamming in the cut. The thin successful cuts were not precisely smooth. There was a very fine ripple perpendicular to the line of the cut that resembled a very fine machine planning cut surface. After testing the frog bed, and the frog for flatness, I saw that the blade itself was very slightly flexed or bent across the width about where the lever cap attached. For that I bought a new blade, one of the Hock made thick blades. It’s hard to find N0. 10 blades, but Hock makes one. Works fine now.

“Design your life to minimize reliance on willpower.” — BJ Fogg.

My takeaways from this: Have your sharpening setup looking at U in the face, and as Paul says have an expectation of sharpness and accuracy always in mind.

I try to avoid buying wood and spend time sourcing old furniture to up-cycle. It is always disappointing to find a nice piece only to discover it is veneered chipboard or MDF. Although I am sometimes able save large flat pieces in good condition by cutting them to size and re-edging the material.

My favorite plane is always the last one I sharpened 🙂

I love flattening boards with a hand plane. The snick, snick sound is better than doing yoga. Recently I found some oddly shaped off cuts of Claro walnut in a bin at my local wood supplier. Getting them four square with a plane was very satisfying. Learning to sharpen them properly was a big breakthrough. Thank you.

Couldn’t agree more about the soullessness of MDF. And that really highlights what handcrafted real wood creations are all about – soul.

Thirty years ago my kitchen project went right off course when the whole budget was blown on a double width cooker when we were going to reuse the old one… A friend suggested that I make some cabinets from cheap MDF and rebuild them later when they started to fall apart. They may be the only dovetailed MDF kitchen drawers on the planet and a three foot wide full depth full extension drawer still carries a full load of cast iron kitchen pots, I must repaint the draw fronts one day…

I am not too sure what wood I could have, should have used to survive that long in an unheated kitchen but now that I am trying to work to a higher standard I would love to try.

“Much ado about nothing” takes on a whole new meaning when it comes to reaching that 0º point where the two surfaces of the blade you’re trying to sharpen meet.

Interesting that you have no Architecture texts. Not even a Nicholas Psvener or a Pugin.

Agree on how much wood moves, I’m the editor that glued beech worktop to strip of sapele, to the detriment of the beech worktop.

I think David Charlesworth has the best furniture with regard to precision and accuracy but no one has the time to copy him, your joinery is so much more real.