A Wonderfull Book For Your Library

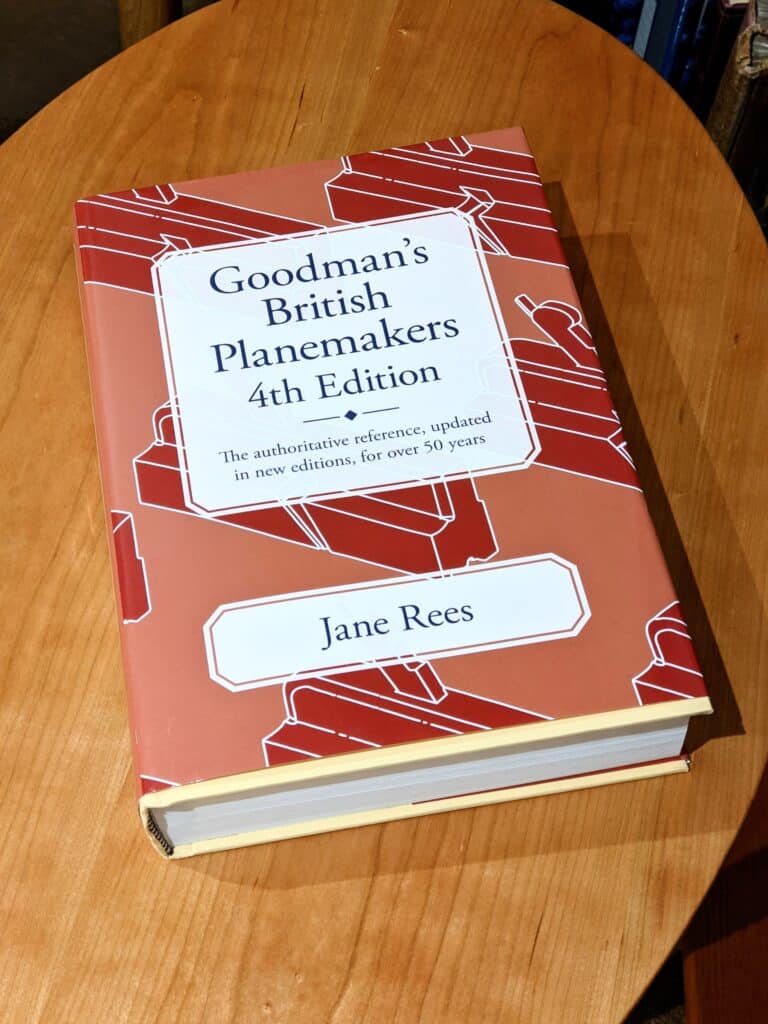

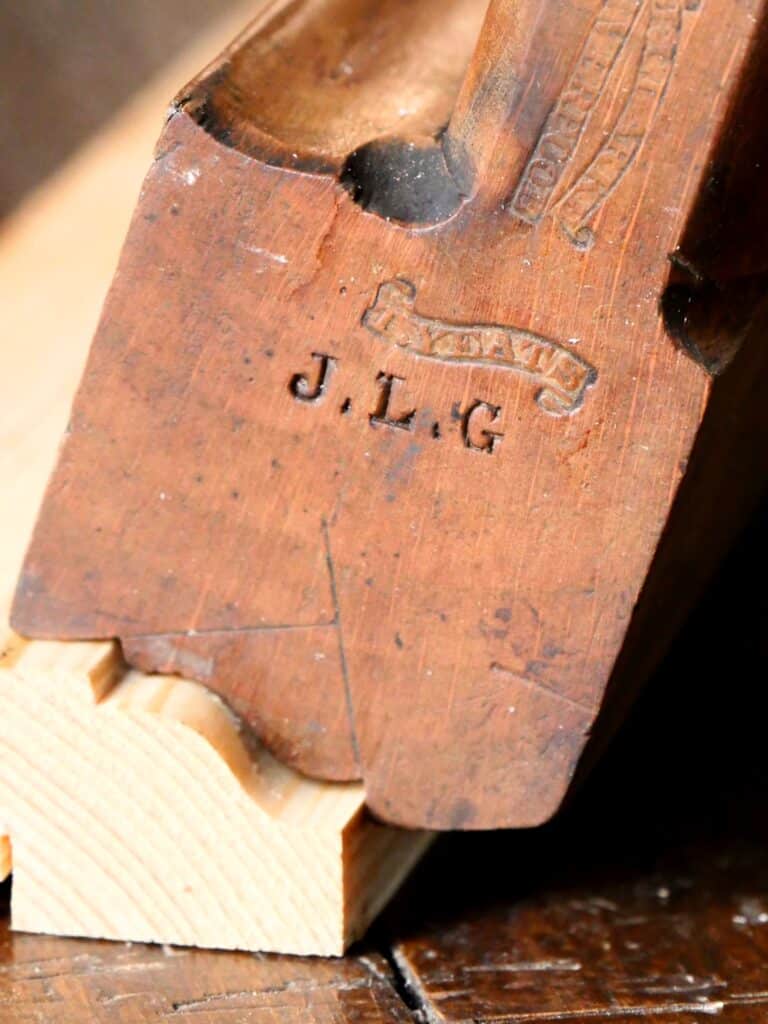

I was reading a comment in the most recent edition of Bill Goodman’s Plane Making from the 1700s book which is now the continued work taken over by Jane Rees under the title ‘Goodman’s British Planemakers 4th Edition’ that intrigued me but left me questioning. The book is a veritable tome of almost 700 pages, so not a good bedtime read as such unless you have strong arms. As it says on the cover, it is an “authoritative reference, updated in new editions, for over 50 years.” Bill Goodman’s first edition came out in 1968 with an updated version in 1978. With three and a half times the number of pages in the latest publication, very little seems to be left out, but, as with all historical reference works, new evidence yet to emerge often discloses new facts. When it comes to identifying, tracing and dating your woodworking planes made by the UK makers from wood, this book does it. The book offers even more than that. Tracing the path and passage of planemakers from throughout the UK provides insights to the industrial shifts leading to the development of societal changes, some collaborative efforts such as the workshop of thee carpenter aboard the now raised Mary Rose from the 1700s. I thoroughly, thoroughly recommend this book to you. I have enjoyed catching up on the missing makers now included in this volume. There is much information about the historical paths taken by makers and then there is the corroborative work of extensive new finds to support theories as new realities.

Though the names on the cover reflect a major investment of time and effort, this more comprehensive and extended work comes from the support of those who knew of or collected the work and examples of makers and users through three or so centuries. If you are even remotely interested in dating the wooden planes you own as users or collectables from mostly UK makers and distributors, this book is a must for you. Nostalgically, I will always pull down my 1978 edition for a quick thumb-through search, but the newest Jane Rees’ version is well worth adding to your library.

I prefaced what I did before this next section because I think what I noticed is important to consider. It’s a small criticism and not intended in any way to detract from the marvellous work exemplified in the book. Sometimes things are said in books that may not obviate a lack of actual working knowledge that sometimes comes more definitively through experiential working knowledge. By that I mean you can write about the history of many things but some things only come through the working of tools in the hands of experienced users. Whereas you can make many direct evaluations pertinent to a tool that are indeed very obvious, it’s in the actual working of the tools and equipment themselves, perhaps more on a daily basis and over a prolonged period, that things become critically seen, that impart realities not otherwise apparent. As a small example, the following anecdote might help. My perhaps irritating endeavour to question why we lay planes on their side comes from my never seeing or working with full-time plane users in user-realms lay their bench planes on their sides. It was a development from school use that children were trained to lay planes on their sides. Kids plonked their planes on top of other tools and the insistence of laying them down sideways made the kids more sensitive to being more careful, nothing more. The carryover to the benches of adult woodworking in domestic or hobby realms is, for me at least, plane silly. The only time I might have seen a plane laid on its side by daily users was in someone’s home, office or business where the plane itself could have damaged a non-work or furniture surface. This brings me to my reason for this blog post. Occasionally a writer will put something down in print that then becomes both sacrosanct and permanent. Sometimes it is simply a mistake, an assumption, naivety or simply a personal opinion. Other times it is meant to be smart-alecky. Either way, it is best to put something out there to correct a possible wrong and I submit the following to that end.

Reading through the Jane Rees’ edition her,e I came to this intriguing section where a couple of things jumped out to me as incorrect perspectives. “In general, British planemakers were astonishingly slow to react to Stanley’s Bailey-pattern planes that were ultimately to take over much of the market. The Stanley planes were about one-third of the price of an English dove-tailed steel equivalent.” The text goes on to say that in “1905 a Stanley No. 4 cost 7s 0d (shillings) whilst a 2″ dove-tailed steel, handled smoothing plane cost 21s 0d (21 shillings) – and the English plane had no adjuster.” We should indeed consider this more fully. Where it is said that “the English plane had no adjuster“, it did not mean that it could not be quickly, easily and readily adjusted with abject ease by any skilled craftsman user. Whereas we should remember that today’s dabbler into the use of moulding planes might well indeed struggle badly to set any wooden plane with a wedge-held cutting iron, users of the day were well-practised practitioners and they would indeed hammer-tap and bench-knock a plane in a split second, using methods most of us have never considered or known. These methods worked amazingly well and might well have been much quicker in most cases. It might be worth noting here that many all-metal, adjustable planes have cutting irons, that have the evidence of hammer-tap adjustment on the cutting irons be that for lateral adjustment or depth. Old habits die hard, especially when a former method was indeed quick and easy. These planes had both depth and lateral adjustment mechanisms, I hasten to say.

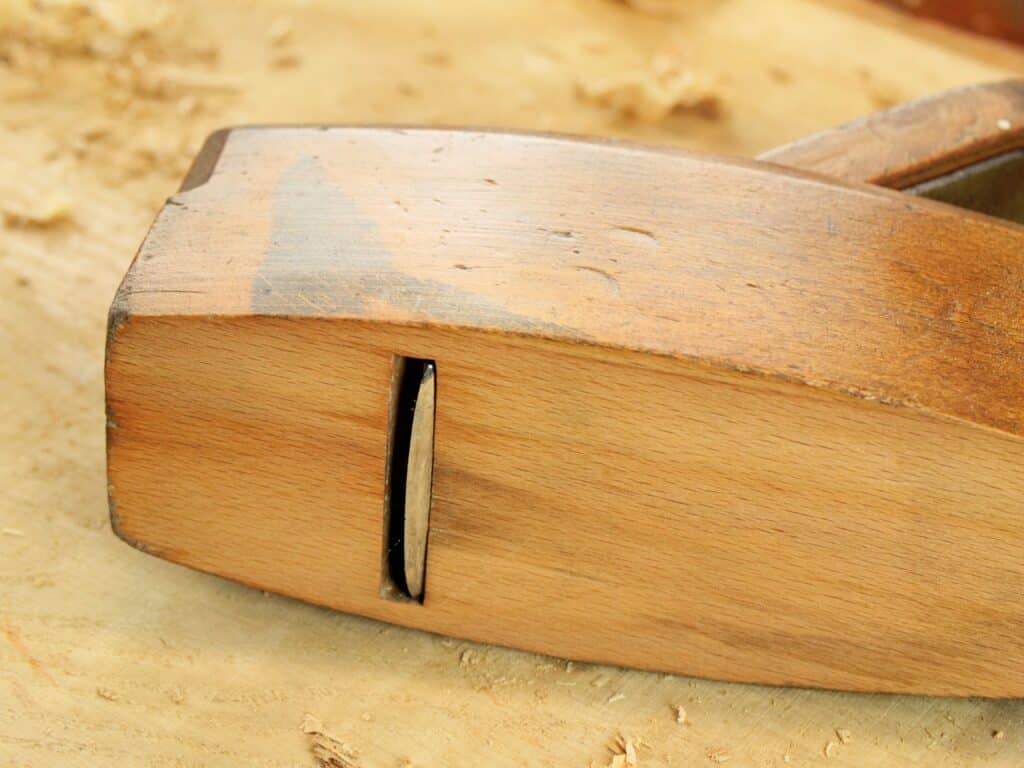

So, to compare the entities by cost alone is quite insufficient. Many cultures still make wooden planes with non-mechanical depth and alignment adjusters and use them with amazing alacrity and accuracy. It might seem to some from what’s written in the book that wooden planes are somehow outdated and that a non-entity is the reality that wooden planes glide beautifully over the wood with amazing ease, requiring a mere fraction of the energy of any and all all-metal plane versions. I doubt that we would say that Japanese craftsmen through many centuries and still in our present age, still using wedge-held wooden planes, to be “astonishingly slow to react” and this is almost a century and a half after the Stanely #4 was invented. So too many European makers and much of the whole of Asia also. I think this might explain why users of wooden planes would not give up their planes. Why, in that era, would a well-versed crafting artisan with many decades and years under his belt replace them with the new all-metal versions? The reasons were less to do with the Stanley giving a better option of a plane and neither was it a better mouse-trap option. They most certainly were not dullards nor Luddites standing in the path of progress, but more the considerate artisans respecting the efforts of entrepreneurs but finding no need to change at the time. It did take half a century for Stanley to persuade existing users to accept what was actually a sluggish plane when compared to wooden versions. This was more to do with each generation not recognising the value of wood on wood, the demise of the wooden planemaker on the high street and then the less expensive manufacturing costs of all-metal planes. Remember too that from tree to workbench as a user plane, a blank of plane wood would actually be several years.

Additionally, wooden planes were much lighter in weight at the workbench and in the zone of working. A wooden smoothing plane and its longer counterparts were a fraction of the weight of the Stanley range of bench planes and all the more so than the newer heavyweights introduced of late by so-called premium makers. Whereas we currently extol the virtues of special steel alloys used in planemaking these days, wooden planes lasted very well. Yes, of course, they did wear, but as the sole wore down through years and decades of use, and the plane mouth or throat widened and became too enlarged for the finer work they might have originally been fashioned for, they went on further to be used as the roughing planes we now call scrub planes. These were used to prepare the way for the other bench planes.

That wide, open throat would remove heavy shavings and masses of wood left by conversion in the milling of wood from trees to slabbed wood. No metal plane really equalled their functionality for removing saw kerf and in such wide swathes. These well-worn planes, having retained continued functionality in a slightly different sphere at the bench, were rarely completely abandoned. Only when they were worn down to the nub were they pensioned off. I should of course add here that they were often redeemed for further use by adding wooden inset throat closures to the forepart of the plane sole as often as necessary and sometimes several times too. They might also add a metal plate to the full coverage of the sole.

Whereas wooden planes were never designed nor intended to be thrown in the bottom of a toolbox or the back of a truck, the cheapening of planes by producing the Stanley type of plane seemed to somehow conjure up this kind of attitude with some carpenters. What Stanley offered in the Bailey-pattern bench plane really was a low-skilled version of plane making by deskilling the methods and types of production. The evolution of mass-making, as it so often does, reduced the care a craftsman might place on his and her tools. Especially does this become so, when the tool itself becomes disposable throughout its material construction. Handsaws are one of the best examples. Casting fifty planes all at one pour of molten iron and then bolting in place all of the components with no actual refinement needed, took a mere fraction of the time it took to make a wooden plane body replete with wedge and cutting-iron assembly; almost zero woodworking skill when compared to making wooden-bodied planes using traditional methods. Creating and fitting wooden planes, forming and shaping the throats, fitting the cutting iron assembly and then making, shaping and fitting wedges etc was highly focussed craftsmanship in a small area of woodworking, but nonetheless, it was skilled workmanship requiring extreme levels of dexterity and accuracy. Comparing the minutes it took to cast multiple all-metal-cast planes with the hours, days and weeks it took for their wooden counterparts is not comparing apples with apples. The outcome was very different too. The end result, whether we like to admit it or not, is that the English users were not at all “astonishingly slow“, as suggested, but that they simply favoured their own amazing planes and they did not pursue the ‘mighty dollar‘ saving because they had something that was actually well-suited to the work and superior in the first place.

Of course, Stanley did not leave it at that. It went back to the drawing board to design a plane with a wooden sole and all the mechanisms of its full Bailey model, ie, lateral adjuster, moving frog and a wheeled depth adjuster. This Stanley model #36 came out in the early part of the 20th century and became popular to bridge the gap between all-metal and all-wood versions. Stanley was undaunted by any and all rejection. The funny thing for me is that the wooden sole with cast iron framework works so beautifully, lightens the weight of a regular #4 by almost 30%, what is there not to like about it? Nonetheless, it was an intentional move to transition from one camp to another. The deed was done and Stanley’s success once again was secured.

The next paragraph too is a somewhat inaccurate evaluation of the time. I wonder that the author/s didn’t ask why multiplanes were often found with almost zero usage and with full-length, unrefined or minimally used cutters rusting in the neat packages in the boxes. I think that this question alone would have been greatly insightful and I say this because it is obvious that such planes were seldom used and for good reason. In the reality of real woodworking at the workbench, the combination planes worked abysmally poorly. I doubt that many experienced woodworkers can take more than a few strokes without the grain rising, jamming and tearing out the grain, no matter the wood type. The sentence, “They were even slower to respond to the Stanley Multi-planes, the 45 and 55. These combination planes were introduced in 1883 and 1897 respectively and were intended to replace a plough plane, a dado plane, a fillister and beads and sash planes all in one tool. The Record 405 Multiplane, a close copy of the Stanley 45, was not introduced until 1932!” Notice the exclamation mark. Again, other considerations should be considered here. In the British woodworking workshops of the day, the shelves and chests would be lined with a few hundred different moulding planes of every shape and size. These all had proven technology woven throughout their fibre fabric. The thought of the day would have been something like, “Why fix what ain’t broke?” I might suggest. Another truth is this. These multiplanes did not only not work well at all, but they were also quite awkward to use, awkward and unpredictable to set up and they tore grain up and out on a stick of moulding like no other plane ever invented. This is of course the cause of great frustration to any woodworker. Another consideration is how badly they perform on end-grain cutting too. Worth considering also, regarding the slow uptake of manufacture by Record, UK: I wonder, as the dates given show an almost 50-year difference, would existing patents by Stanley have prevented such manufacture by Record?

And then there was this, “Quite why the British trade should have made so little effort to develop and market this type of improvement is a reflection of the extreme conservatism of the joiners and carpenters of the time.” I hope that I have convinced everyone here that the multiplane was not the ‘power router’ of the day but without the electric motor. The handheld power router is of course a remarkable machine. In the industry of woodworking, it would be hard to replace for all of the tasks you can achieve with them. At about the same time that Stanley was inventing its combination planes, a foot-pedaled version of the shaper was patented and 1906 produced the first portable power router with an electric drive to power it. I think that then the writing was on the wall. It was only a question of time before the handheld, battery versions with plunge ability and soft-start power routers would come into full-time use in any carpenters hand. There is no way a joiner and carpenter will trim out a house in a day or two with hand planes such as moulding planes, rebate planes, plough planes and so on. Going back though, the joiners and carpenters of the time were the potential buyers. The planes offered were highly innovative, yes, and some metal planes offered were just fine, but they often were not superior or improved on and a master craftsman of the era would not be likely to advise his prodigy apprentice to buy something that was possibly inferior to what he used. I doubt that this was resistance to progress so much as the reality that what they had worked really well.

I will concede that we users are reluctant to change for the sake of change’s sake but we do consider tools for their functional merit. A point in case is the more modern Shinto saw rasp. Others had nudged me to adopt one for trial and I did. I found it ugly in appearance and wondered if it would be more like the Stanley Surform that came out somewhere near the mid-1960s. I strongly disliked almost everything about the surform but can see why it became popular. There was no adjustment needed and anyone can use a cheesegrater to shape wood with.

The Shinto on the other hand is a radical shaping tool altogether and outshines the Stanley Surform a million to one when it comes to woodworking. It is possibly the kind of tool I might take 4mm of the bottom of a door with, especially the end-grain of the stiles but then too I would shape a guitar neck with it too. How does it compare to a hand-stitched rasp from a premium maker stitching every barb by hand and catering to the sweep of an arm movement? Well, it’s not that far off but it is I would say a lesser tool. Whereas I would not use my rasps for the bottom of a door needing clearance over a rustic gravel path, I would use the Shinto but hesitatingly so. The wonderful thing about it is that it works extremely well, offers two levels of cutting in a single tool and it costs about a fifth of its hand-stitch counterpart. Does it replace the better one? Not for me, but yes for someone with kids or a budget limit or a dozen other reasons.

The multiplanes never offered what moulding planes did. To get any level of success you had to have the kind of wood available from harvesting virgin oaks and mahoganies beneath dense canopies that stood themselves for 200-300 years and more. Those days are mostly gone for us modern makers. Limbs spread in the lower density of today’s managed forests have more side limbs anchored to their root in the stems of the trees that result in many knotted areas. And it is the knots that cause the greatest deviations in our wood. These deviations cannot generally be shaped and planed by multiplanes of any type. You must also remember that massive mouldings in skirting boards, dado rails, panel frames and door architraves were made up from parallel grooves side by side and formed using plough planes followed by moulding planes. By first running some grooves, an artisan could broaden the offering by using moulding planes alongside or into the grooves. Hollows and rounds, complex moulders and such, established long runs of moulding at the workbench before going out to the building project. The all-metal plough planes never really encountered such work as this was the era many manufacturers never saw coming. The era of the combination plane was indeed short-lived. Machines were well underway by the mid to late 1800s all be that they were driven by water, wind, steam and water-driven turbines etc. All that was needed was the development of the soon-to-be electric motor to replace the take-off belts that then drove the waterwheel, or the wind-driven mills and animal power. In the sage words of the great Bob Dylan; The times they [were]-a-changing.

Salesmen try to persuade us that “new” equates “better” and “useful/necessary”. Sometimes while simultaneously making reference to tradition.

I am regularly buying some fresh cheese which branding has changed a few times in successive take-over while the general aspect of the package remained more or less the same.

The last time one could see simultaneously on the package : “new formula” and “since 1872” (translated from French).

I wander if the formula really changed as taste and texture remained the same.

Most business models nowadays need alleged and planned obsolescence.

I too like cheese, Sylvain. My grandmother used to take me to the local shops in Gent to buy some “délices au fromage” (cheese delights) for us to share, together with some bread from the local bakery. When she sent me alone to the bakery I would have practice my Flemish by asking for small loaf with the sentence, ‘Kleine betcher brood, alstublieft!‘ The baker answered, “Graag gedaan!”

Wonderful!

I’m from Ghent and my dad is an Englishman.

I wonder where in Gent little Paul bought his bread…

Louis Pastoor Bucker straat???

You do impress Paul. I wonder what those Americans thought of that? My first experience with an American from the South (by her accent) was quite comical – she was obviously impressed by my English, after I’d responded that I was from Australia. I know that it’s legendary the confusion between Austria and Australia.

Anyway, impressed as always.

Sufficiently impressed with a previous video on molding planes to I buy my first antique molding plane the other day on line. Looked OK, but we shall see if I can get any nice curves out of it when it arrives.

Paul, have you tried the Veritas Combination Plane?

I own their plough plane. I understand they followed the pattern of the Record 044. I’m not interested in combination planes except on a more limited level for ploughing grooves.

I get it! But the plough plane, because of the grain orientation, do you need to have two, left and right, or am I wrong, having only one hand does it?

And thanks for answering the previous question!

Now about the book, I’ll think about it. I’m Brazilian and here in Brazil it’s not always easy to get these books. But it looks too rich for historical knowledge.

William-

You only need one. There are 2 solutions, the first is simply flipping the fence tothe other side of the plane, this works well on the old Stanley and Record, I am not as sure about the Vertias. The second is pre-sliceing the edges of the grove, much like cross grain work, and taking shallower shorter cuts.

Being Brazil you are swapping book availablity for local access to amazing hardwoods.

Evan, thanks for the tips! I’ve even been thinking about having just one.

About books, when it’s a book that interests me a lot, I import from international stores.

About wood, we have a good variety. This is good!

Hi Paul, I’d really love to ask as I’m 27 and know few woodworkers those I do just use power routers. I recently got a 405 and lots of profile cutters and I am realising the common issues, but I can’t afford or find large mouldings for my projects like crown and base trim I can’t seem to find affordable wooden planes that aren’t badly damaged. I don’t know where to go from here I want mouldings but I don’t know how to proceed towards it. I just find myself using my #3 #4 and #5 on various angles but I was looking for something more elegant. Thank you for all your work.

Thanks for the update and comments on what sounds like a great, interesting book. I had considered purchasing it previously, but still hesitate as I don’t need any additional influence to jump down yet another rabbit hole and find that I now ‘need’ to purchase a whole slew of interesting and nice moulding planes, especially at my age (humor intended…) I would disagree with your evaluation of the Shinto rasp, as mine affords me 4 different levels of service – coarse and fine when pushed, less coarse and finer when pulled (or pushed handle first) for detail work. That provides a little more cleanup before switching to files, for me at least. Many thanks for the great videos and blog shares, always enjoy.

Hello Kerry. I want to understand more and I’m not sure what I said negatively about the Shinto saw rasp. I think it is a remarkable invention and the inventor deserves full credit.

I believe I misspoke when I said ‘I would disagree’, I should have said ‘add to’. I love the Shinto, and reach for it often, as my Sureform slowly rusts away in the corner. I merely wished to say that through not using the tool as originally designed, i get four levels of cutting from the rasp, as opposed to two. I often have been known to drag files backwards, also, for the same effect. My apologies, no criticism meant – I appreciate your shares way too much to do that.

I agree with your and Paul’s opinion of the Shurform by Stanley. However I have hundreds if not thousands of hours using them. They work great on plastic body fillet (Bondo) or faring compound on boats. But Never in a thousand days would I use them on wood.

Andy

The guys at home use them all the time for shaping surfboards – clearly just foam.

I did try to use one on timber for something, but it was hopeless (or perhaps the operator).

I am a decidedly amateur woodworker and love my wooden bench planes: 2 x try planes 3 x jack and 2 x coffin smoothers. I have put on new soles when needed. The smoothers are wonderfully versatile and allow you to push with the heel of your hand almost on the wood. All are easy to adjust once you know how: tap with hammer to increase depth or lateral adjustment or knock the top of the toe on the bench for less iron. All very quick.

Hi Paul

As always, an informative and thought provoking piece, thank you!

Below the 4th picture you mention “This is indeed one of my favourite planes to use” and I remember admiring it previously, several years ago. At one stage you tempted us with a “I’ll show you how to make this plane using the frog of a broken bailey” or similar words … that particular project apparently got overtaken by so many of your other excellent works, but I wonder if it is still in your future plans?

Thanks again for all you do to keep these skills alive.

Chris

I thought I had seen on YouTube Paul making a Marples style plane but maybe I’m mistaken. It may be that it was indeed the suggestion that there would be a video in the future?

Hi Paul,

Thanks very much for all this as I share your interest in the history of woodworking. I wondered if you had insights into Pollak’s A Guide to the Makers of American Wooden Planes, Fourth Edition.

I’ve been given half a dozen wooden planes. In France, the large ones are called « varlopes » and are very common but not sought after. Nevertheless they are extremely efficient tools.

On some of them, the sole shows a lot of wear and is not longer perpendicular to the sides of the plane. I imagine that the reason is the natural deviation from the vertical of the human hand/arm, exerting more pressure on one side of the plane than the other.

Wanting to restore the planes to use them, I was asking myself if it is necessary to plane the sole up to « perfect » perpendicularity with the sides (that would imply removing quite a lot of wood and perhaps re-sole the plane). Or just make it flat, remove enough of the angle to be able to align the cutting iron with the sole, close the throat with a small piece of wood … and live with that.

After all, the past owner of the plane has done so ! Was he a careless man or a skilled and productive woodworker who has adjusted to the wear of his tool ?

Thank you in advance for your thoughts and advices …

“remove enough of the angle to be able to align the cutting iron with the sole,”

One has always to have the cutting edge grinded/sharpened parallel to the sole (as an extreme case: like on a skew rebate plane). This means one might not be able to use a sharpening guide. Hand sharpening only then.

The only (maybe) annoying feature is that the handle is not anymore perpendicular to the sole.

Mo,

you might be interested by an old video from the RTS (Radio television suisse) in the “La Suisse au fil du temps” serie with the title

“Les outils de bois”.

One can see the making of a new “varlope”

At about 10’23” the guy place a new iron in the body to see how to grind it. He says they come square when new and have to be grinded to be adapted to the plane: “on l’affute de façon qu’il soit ajusté au rabot, de façon qu’il dépasse de chaque côté la même chose”. He then verify that the iron cutting edge is parallel to the sole.

Sorry web links are not allowed here You would have to use a search engine.

If they are that worn, the best answer maybe to simply re-sole them. The mouth will likely be a bit wider on one side than the other, probably open wider than ideal from usage. I would consider attaching a nice slightly oversized hard wood sole about 1/4 to 5/8 thick then square that up to the sides of the plane, then you can open the mouth matching original angles.

This kind of fix was common enough historically, no reason not to use the same solution.

Oh this post hits home on so many levels. I recently had an actual argument spending the day with a friend in his wood shop – over of all silly things whether to lay a bench plane on it’s side! I have spent the better part of this last year using 2 wood hand planes I picked up used a while back. I was so slow at setting them, I actually decided to put the metal planes away until I got better setting the wood planes with a mallet. It makes no earthly sense to lay these planes on their sides as it might actually change the setting – yes, a slight chance but one all the same. The people who have had that pounded into their heads all seem somehow to think this rule is set in stone. I give up – “their shop their rules” is how I look at that now.

I am so thrilled to have gained some insight, skill and a bit more history using these older wood planes and they do work amazingly well. Nothing glides over wood quite as well as a wood sole of a hand plane. Thank you for opening my eyes and mind to the older tools, we are missing out on something when the world thinks only a new tool works because that is what is available on the market. Keep up the good work!

I am a 74 year old retired carpenter. I still have most of my hand tools from when I worked, and a work van full of portable power tools, so essential back then, but now largely unused.

Once again, thank you for the Shinto rasp tip. It has replaced some old and tired wood rasps that were my favorites for years, even though they had long ago lost their cutting edges. And for your diamond plate sharpening system. I used to carry a two sided oil stone in my portable workbench to keep my chisels and block plane sharp. They are now retired and resting in a drawer. And lastly thank you for the leather strop. I used to strop my chisels and plane blades on the palm of my hand, because that is how the carpenters I learned from in the 1960’s did it. We worked on the jobsite, so everything we used had to be easily packed up and put away in our trucks every day. Maybe that’s why they didn’t carry a leather stop. I never had sharper chisels and planes irons than I do now.

I injured my right shoulder 2 years ago which caused me problems as a right-hander so I started using some Japanese saws and 2 Japanese planes. I also started using Wooden Western planes and found them to be great and very easy to adjust. In fact, getting the blade just right is much easier than a metal plane. I decided to avoid any and all surgery as at 72 years old I thought that too risky. Two years later my shoulder is working very well so I returned mostly to my Stanley # 5 for the rough stuff and some Western wood planes for smoothing and finishing. I am back to my Western saws as they are fast and efficient. Paul’s videos and emails have guided me along my path to recovery and to become a much more thoughtful and effective woodworker at 74. Thank you for everything.

Well I’m sharpening irons at the moment, I have recycled a large number of red cedar planks and Douglas fern timber from engine crates at work, no idea what to do with them? Just can’t see them go to waste!

Agreed and well said.

I think too many look for scapegoats when talking about the decline of the hand tool industry. Bad management if not cost cutting accountants typically cop the blame.

But as you say the times they were a changing and in reality no group of people can be blamed. Once machinery was developed and then products like metal windows (1930s?) demand for hand work and sales of hand tools was always going to fall off a cliff whatever the makers and manufacturers did.

And presumably (like today) manufacturers in the late 19th / early 20th century also had to compete with massive pools of no longer needed used hand tools. If your wages are falling and work is getting scarce then buying new tools is not going to be on your agenda.

The fall from huge, strategically important industry to niche by-water was outside the control of all involved in hand tool making. Even mighty Stanley are now a tiny fraction of their former size.

I too have a copy of Goodman’s 2nd edition – this now seems to have been a good investment financially as well as for the obvious reason! Is this another example of the Paul Sellers effect?

A quick glance at Amazon showed at least 5 different Shinto type rasps. I wonder if one is a better general purpose tool to add to ones armory and why.

I have used two of them to date. The longer 11″ version, which is almost 18″ including the handle, and the short version which is about 9″ plus the handle. Whereas they both work well, the longer version is my preference in daily use. That said, the short version will, I am certain, prove itself in tighter work where short turns and twists of the wrists require a shorter distance between hands. It will also work well for those of smaller stature as in the child range of child heights and weights. The contrast between the plumb coloured painted wooden version and the rubberised ergo version is mainly aesthetic, I think, at least. Sometimes you want a handle that slips and slides and glides between the hands and other times you want something that just grips. Hard to say which will work best for you but I suspect the one that will eventually be dropped is the wooden version, so maybe if you want one of these you should go for it now.

Paul,

I have used my 11″ Shinto rasp long enough now to share a modification I use that works. I wrap the non-handle end with two or three wraps of duct tape, and it is much more comfortable in two handed use. I used to do that with hacksaw blades and Sawzall blades on the jobsite when I needed to get into a small space or to do a more delicate job.

Part of the critical commentary on the Jane Rees’s “Goodman’s British Planemakers 4th Edition” reads:

“The text goes on to say that in ‘1905 a Stanley No. 4 cost 7s 0d (shillings) whilst a 2″ dove-tailed steel, handled smoothing plane cost 21s 0d (21 shillings) – and the English plane had no adjuster.’ We should indeed consider this more fully. Where it is said that ‘the English plane had no adjuster’, it did not mean that it could not be quickly, easily and readily adjusted with abject ease by any skilled craftsman user.”

This reference in the book to the English plane having no adjuster is one of the things characterized in the critical commentary as being amongst “a couple of things (that) jumped out to me as incorrect perspectives.”

However, given its plain English meaning, that passage of text may not be construed to say that the “English plane” had no method of adjustment. Its plain construction is that the “English plane” had no mechanical device for adjustment. There seems nothing of the “incorrect perspective” about that at all. The criticism merely seems to be an attempt to impute to the author of the book an ignorance of methods of plane adjustment where an adjustment mechanism is not present.

There then appears this puzzling passage of adverse criticism:

“The end result, whether we like to admit it or not, is that the English users were not at all “astonishingly slow“, as suggested”.

Again, however, the suggestion that the English users were “astonishingly slow” is not made in the book. Text from the book as quoted in the article reads:

“In general, British planemakers were astonishingly slow to react to Stanley’s Bailey-pattern planes that were ultimately to take over much of the market.”

The planemakers stand clearly suggested in the book as being “astonishingly slow”, not the plane users.

Notwithstanding this inaccurate criticism of the non-existent inaccuracies in the book I am pleased to have had its existence drawn to my attention and look forward to making up my own mind as to its merits.

I do not regard myself as a highly skilled woodworker but I have never had any real trouble with adjusting wooden planes, knocking the nose on the bench or tapping the iron to advance it, knocking the heel on the bench to retract the iron, tapping a side of the iron to adjust it laterally and always following up with a tap on the wedge to hold the position of the adjusted iron. Each of my wooden planes seems to respond to these ministrations in its own fashion in terms of degrees of amplitude of movement of the iron in the desired direction but one grows accustomed to their little idiosyncrasies. I think H.N.T. Gordon, a maker of wooden planes, has a video on the subject.

I have re-read both the original post and your comment. I think the problem may be in Jane Rees’ use of the word “astonishingly” in the phrase quoted. I agree with Paul that this implies that the new design was definitely and obviously better – some disagree.

As to the cost comparison, why buy new when you already have a perfectly good plane?

Oh and incidentally my grandfather (a shipwright and later cabinetmaker) was one of those men. He made his planes as an apprentice – why would you give them up?

Always love the plane posts. Friends are astounded by Paul’s beautiful drawings in them. I’m reminded (by the picture of one) that there were plans to video the conversion of an old Bailey to a wood sole plane. Some problems arose and the series never happened. Could that be revisited? I bought a cheap plane I was going to use in the effort from Home Depot or Lowes. It is a Kobalt. Very heavy, but otherwise really nice and adjusts well. Have you seen one of these? Best cheap one I ever found. A wooden sole would lighten it up. I could proceed on my own since Paul produced a drawing. But I love Paul’s tool making videos the best. Also very interested in a parts kit for the router plane. Thanks.

Paul produced a drawing for the wooden body “Bailey” plane? Can you share the link?

Ron

Two other things I love about wooden planes are they are warm in your hand (in a cold workshop) … and the noise. I love the sound of a wooden plane taking shavings!

The picture of the wooden Bailey pattern hyprid plane in the above blog post is fascinating. It appears that you replicated the body casting with wood, mounted the fog, and away you went. Was it that simple? Did you ever make a drawing or a pictorial of how you made it? If not, please do. I’ve done many searches and haven’t found a diy for that type of configuration yet.

YIC,

Ron

Repurposed is not just for planes. It’s common for cooks to use a heavy chopping blade for fine work for years; and then, when the blade is worn by hundreds of sharpenings, to repurpose it for a bone cutting heave cleaver.

Paul I’ve been using my 3/16″ edge bead wooden moulder, I have several going up in size.

I had selected a really nice knot free couple of 2×1″ at 3′-0″ long. Straight grained. Within three passes I had a superb edge bead.

BUT because I didn’t fully check grain, one piece had a tiny swirl of grain resulting in a very annoying tiny tear in moulding.

No amount of carefull sanding could correct tear.

Luckily I was able to carefully use my two lengths without this piece.

Looking back and now looking forward I will check grain direction and by carefully cutting fibres-before using my moulders.

Paul am I correct in saying that pitch pine did lend itself to easy use of moulders, as it can be straight grained and knot free.

I would really appreciate a reply please……..thank you John 2V

Hello John, Some moulding planes were made in pairs and could be ordered as pairs if relied on enough in particular elements of moulded work for that very reason, so one might be forgiven for thinking that they were handed for left-handed people when they were made in popular types so that when grain reverses the awkward grain can be intercepted by a change in direction.

Re pitch pine: Pitch pine derives its name from a variety of pine that was forested so vastly it covered the whole of the Eastern Seaboard of the USA. Millions up millions of acres of Longleaf pine, (Pinus palustris) commonly referred to as pitch pine, was reduced over a number of decades in volumes you would think could never happen yet less than 35,000 acres of that forested region from Maine to Florida is standing today as a protected species. Long-leaf pine is so called because of its superlong pine leaf. Until you have worked with the wood it is hard to imagine its incredible properties. Incredibly dense, strong, hard and much more, I count it a privilege to have known and worked with it over the many years that I did when I lived in Texas. Indeed, I still own a couple of pieces made from Longleaf pine. The trees grew to massive heights and girths and was used especially in large volumes to construct the frameworks and flooring in the pre concrete days of factories, offices and homes. Old virgin growth longleaf pine grew to 47 m (154 ft) with a diameter of 1.2 m (47 in). I acquired my stocks from demolition companies back in the 1990s for about a decade. The growth rings on some beams and joists could be 1/32″ apart which shows just how dense the canopy was. Once the canopy was gone and the open skies brought on second growth, that narrow band increased to 3/8″ and a fast growth where the wood itself, together with its properties resembled more the southern yellow version of pine much lighter in colour and density. The resin in the pine seemed to enhance the workability of the wood so, yes, pitch pine as it was often known “did lend itself to easy use of moulders and can be straight grained and knot free.” Absolutely!