My finished plane story

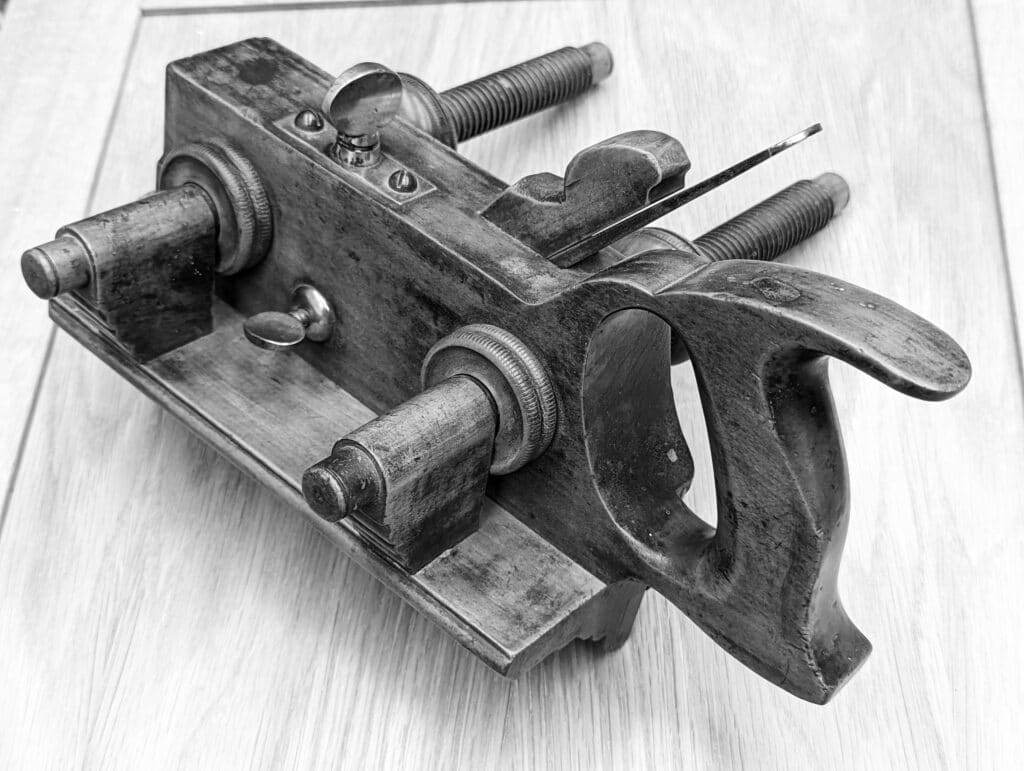

The rounded parts shine as a silvered smile wide-spread from the light shed evenly through the window. It seems to greet my own smile as I stop to take in the sight. I doubt whether others know it to be a remarkable thing for a wooden plane’s handle to wear smooth like that from just a man’s hands. I mean, it takes years upon years of handling, spinning, swivelling, turning, pulling and pushing for that to happen and with no varnish or some kind of oil; it takes decades, a century or so. I look more until the whole of the plough plane registers its different parts as images to be fixed, indelibly recorded, in my mind because I don’t want to lose the warmth of its loveliness.

And what of the saw too? I have many old saws beginning life ten and fifteen decades past, yes, a century or a century and a half, I’m quite sure, with the smoothness I speak of that draws the hand so and the fingertips to lightly touch where the shine bends, and light is the touch for fear of disturbing something almost holy, and rightly so, for to a man who makes, his work is honour and becomes his form of worship to respect his own maker.

The metals glisten as hard metal in its glinting often will in contrast to the softness of a wooden tool’s worn places to speak of ages gone that we’ll never know again and most never knew. Odd, that, if you think about it, dwell on it for a minute or two. There seemed to me, at least, always to be the certainty of a certain kind of honesty about the tools made by a man’s hand, according to his name I mean, I suppose, you know, his reputation. Yes, his reputation was reflected as the shine from the smoothness of the surfaces he worked and wore down for decades by his sweat and the roughness of his hands.

And then, I see more exquisiteness just when I thought I was done, in the thin line of registration of the cutting iron along the simplest vee groove chiselled in the back that located in the fore-edge of the rear sole of the plane. How do you explain the beauty of such simple yet complex forethought as this, the blacksmith’s chisel cut that forged the fine detail along the back edge of that long tapered iron? Is it not a lovely detail yet without excess? No one really knows of such things nor the reason for them, let alone sees them, I think. You know, it’s that single strike with the heavy hammer that draws my eye the most, and the blow that sets the chisel edge dead centre along the thinnest of narrow edges like that. I can hear it now as I heard the blacksmith’s hammer blows for 20 years every day in a treasured era past. Watched him too, I might say. It’s a wonderful thing to see the work of a man who made in the work created a hundred and fifty years ago too.

I’m not really sure when the threaded stems for adjusting the fence distance became so finely made and included in the better-made plough planes made of wood. That’s really of no interest to me.

Replacing the wedges for locking the distance with something so infinitely variable yet accurate and positive took a major investment of the maker’s precious time and skill but, again, don’t you think that this is worth acknowledging in the remarkableness of things?

He, the man maker of plough planes, was halted in the comfort of what was common to him, accepted ways, you see, a sort of knowing of a comfortable of doing it, if you will, and discomforted himself by taking his commoner work into new realms with little more than an idea, a thought of inventiveness to better what was with an innovative new. Again, additionally, this was in the face of an onslaught yet to come from a new breed of maker; makers pursuing mass-making methods and systems where makers of metal-bodied planes would soon ensue — Mr Stanley of Stanley fame was yet to become. It was a decade or two to the demise of men called Marples or Sandusky, where the beauty of wood and its idiosyncrasies, personalities that wood alone has, would become outdated, outmoded, big, clunky and, slowly or not, untenable even.

But the screw stems with their beauty formed so in regulating wooden threads of box were really a very fine addition, don’t you think? And when I look at the wornness through so many decades of use I wonder that these makers ever saw (or witnessed) the end in sight as industrialism first crept slowly over their working and then, in a great upsurging tsunami, swept over the worlds of all crafts as a great and destructive tidal wave named progress.

These threaded rods are very lovely in their wornness. Softer now than then, the nuts rotate perfectly as long as you are in a dry place.

They will spin many revolutions to take up slack, perhaps as many as ten. I think too that we might miss something here and fail to see. The infinitely adjustable screw thread for adjustability in the wooden plane was never carried over into the all-metal versions. The one thing about the screw-threaded adjustable stems that no one discusses was how they never ever moved whereas all wedge stemmed ploughs did and so did and still do the Stanley, Record and modern-maker versions too.

The bulk of beechwood grew less in the plane, the low handle, in-line so to now align the hand and the forearm with the elbow in a direct push and pull back, the solidity of a corbelled fence. Someone thought, in the making of the plough plane, of the man who would be using in the making of a future those grooved frames of doors and of drawers for drawer bottoms, of deep skirting boards where the grooves always prefaced the following thrusts with a half dozen moulding planes in hollows and rounds, in astragals, ovolos, ogees and such. You’ll recall, with me, perhaps, a day before the router screamed out for hours on end and working men knew nothing of ear defence, or face masks to keep machine dust from causing cancers in the throat and nose or emphysema in the lungs. You know, when every stroke was paced, measured if you will by the length of a man’s arm reach and the spread, no, more, the stretch and the stride of his legs. When exercise was your work and you exercised throughout the day’s doings.

When you first lift the plane to the wood, now that the plane is broken in after a century and more, if you’re not yet used to it, it will feel a tad awkward. Keep it sharp and use wax or a thin smear of oil to free the sole and the fence from sticking. You’ll thank me for that. I’m waiting for the look and the raising of the eyebrows, the release of the chemistry and such. It’s indescribable. There is no vibration and no grabbing or sticking.

The rights of passage.

Good morning Paul,

I sense the same when I use my early hand saws and hand planes. They are a work of art; appreciated by very few. It makes working in wood very special! God bless.

I have always loved the versatility of threads, although I have only ever cut them in brass or steel.

I much prefer tools to show their history rather than being restored to be better than new as seem to want to do now. Luckily this seems to be restricted to metal planes rather than wooden ones. Many of my tools belonged to relative who have passed away. Using them makes me think of them.

I remember a time when I thought that I was held back by the lack of many electric motor driven tools. Common sense should have told me that the quality of hand made furniture from the past counters this. I had to buy a cheap router to realise that I didn’t really need it, can’t remember the last time I used it.

I am fortunate to have inherited saws and planes from my grandfather and great grandfather, and think of them (channel them even?) whenever I grasp and use them.

I also feel an obligation to look after them and keep them sharp.

Not crazy sharp, but at least as sharp as an oilstone could achieve 110 years ago when the tools were used to make fine joinery.

You are suggesting that for some reason 110 years ago they would have been less sharp? I mean are you saying an oilstone could not achieve surgical levels of sharpness even though the finest work that ever existed in the western world at least is over 150 years old?

Hello Paul,

No, far from it: what I am observing is that craftsmen 150+ years ago obtained exquisite sharpness with oilstones and palm-of-hand strop (I do now use your leather and buffing compound strop design -thankyou) in order to produce their crisp, smooth and beautiful joinery.

They did not need the expensive sharpening ‘systems’ spruiked at woodworking shows and in magazines that seem to be more about shaving one’s arm than about working wood. This was my ‘crazy-sharp’ reference.

I am In fact in awe of what was crafted by hand in the centuries prior to the early 1900s, the last of which I suppose was the Arts and Crafts movement in the western world and the Shaker movement in the USA.

Although more Arts and Crafts than Shaker, the joinery work in the US West Coast architects Charles and Henry Greene’s interiors is just a knockout. There are but a few references in the various books about their work that mention the craftsman’s names.

An architect can design almost anything, but without collaboration with properly skilled trades/crafts, the design will either remain on paper (or computer!) or be compromised.

I am distressed at the de-skilling (total dumbing down) of trades here in Oz: I learned recently that plumbing apprentices are no longer taught to solder.

I suspect this maybe a worldwide trend.

As a cheer-me-up I just love your yew plane handles – they’re alive!

Best regards

Mark Burns

“[…] use wax or a thin smear of oil to free the sole and the fence from sticking.”

I have found it also valid for a Veritas plough plane and a #78 rebate plane.

The oiled rag in the can to the rescue…

Good evening, Mr. sellers,

I mentioned earlier that I had made a Razee style smoother plane, it is a young pup compared to my other, 50/50 split metal and wooden, planes. It is becoming my favourite (perhaps because as made it was far from ideal). Every time that I use it I find something new to fettle, the fit of the tote to the hand, the fact that the wear area angle was wrong , the blade (a very old laminated one)was 2 1/4 and should have been 2 1/2 but that is the fun the, joy of handcraft with natural materials worked with organic tools. Will I recycle my metal planes, only if workshop space crowds them out .

I have just passed our 51st wedding anniversary and my 79th birthday, the candle may be burning down but my brain is still seeking out thing to challenge it.

Wonderful story Paul. I have the exact same plane, a legacy from my grandfather. As I near retirement I hope to master the use of this beautiful tool. All blades have been lovingly honed abd I have a large supply of beautiful Australian north coast seasoned cedar to play with. Keep up your wonderful tutorials as sadly so many great crafts and skills have been allowed to disappear.

I have a collection of maybe 400ish wooden planes that I was incredibly fortunate to be able to acquire while living in the UK. Nothing fancy like collectors would want just simple basic ones. I’ve handled all of them and something that always seems to catch me off guard is how absolutely wonderful and welcoming; even inviting, some of the planes are when you pick them up. Sometimes, I can’t really identify (visually) why; it just is. Each time that happens, I can’t help but smile and wonder how many strokes it took to become like that.

Great story, Paul and some wonderful photography. The black and white images evoke thoughts and feelings of a time passed. Kudos to the photographer and thanks to you, Paul, for your expressive writing.

I used to hate my Stanley 45, but since I paid a good price for it I forced myself to use it and learn how it works. I like it now. Once I figured out that a sharp cutter isn’t sharp out of the box and with a bit of practice the fence no longer moves when I use the plane and if I set things up right (which doesn’t take that much time) things go well.

I once purchased a bricklayers trowel based on the impression left in the handle from the craftsman’s thumb. I knew by looking at the thumbprint in the handle that it was a proper tool. I wonder how many bricks may have been laid by the skilled worker using this well loved and cared for tool.

I wonder if the v-grove indicates the part of the blade that’s heat treated. if your edge goes past that, after many, many sharpenings, it’s time for a new one!

No, that’s not the case at all. The leading edge of the rear part of the skate sole, in the incline, is beveled on both sides and corresponds to the vee in the underside of the cutting iron. This ensures that every time the blade is installed and wedged it is perfectly aligned every time and then too has lateral stability.

The best tools extend humanity’s ability to pursue the ancient Greek notion of arete. Arete roughly means a lifetime in the pursuit of ideals of virtue or excellence. What is it about a tool that turns the force of the closed hand into power to get the job done right? Not just ham fisting and bulling through the work, but doing it with laser precision?

Paul if you could only have one plane for all your work for the rest of your days, which form of plane would you choose?

It would be the #4 Stanley.

I have a similar Sandusky plow that unfortunately has a fairly deep crack running from the nose and into the wedge gap. It seems stable but I’m hesitant to use the plane as sometimes plowing gets a bit rough and I’d hate to be the person who ruins this plane after 120+ years. I enjoy having the tool, but if I’m not going to use it I should probably let someone else enjoy it for a while.

Paul, thank you for keeping the craftsman traditions alive. This article is so appreciated as it helps me keep perspective on what is really important!

And it was a lot of fun to read!

Bill Porter

Bozeman, MT