Times Change Craft

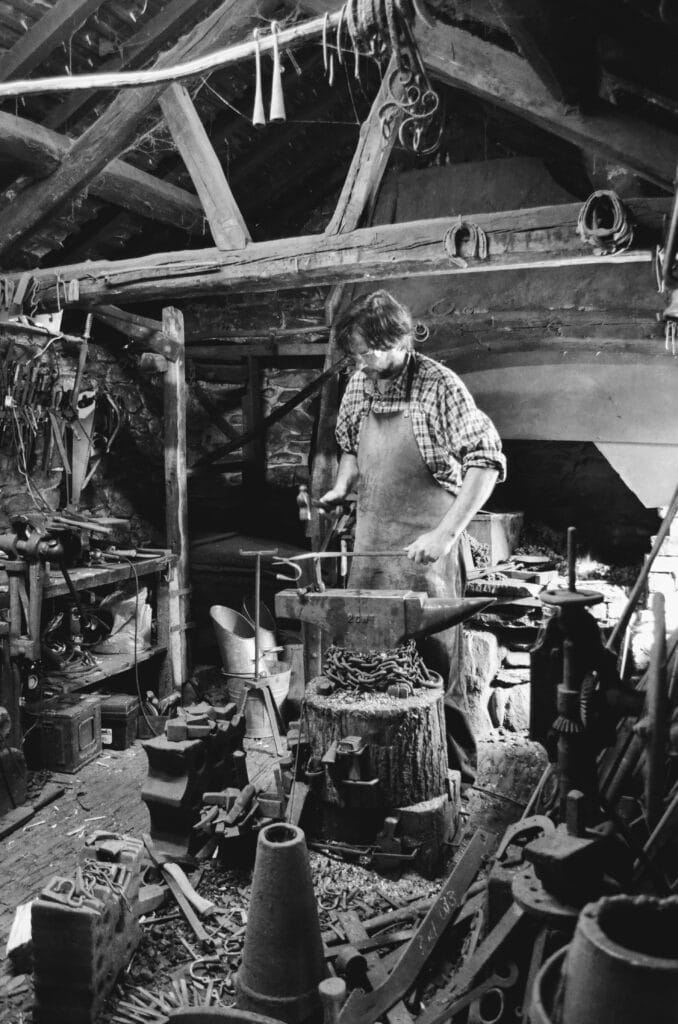

I think we undervalue crafts, now, together with their once-regarded significance in supporting all areas of life. in every quarter of our humanity. If indeed we ever really understood and valued crafts at all in the recent century and more is truly doubtful for most. Why do I say that? Well, I think that people born after a certain date will most likely never have really associated craftworking with the support of agrarian life. But more than that, they never had the opportunity to see or try any real craftworking of any kind beyond perhaps some kind of reenactment. If this is the case, and it is, then they have never been exposed to it in any true and living form. I count myself fortunate. I have! I have lived and worked alongside many practicing artisans and watched them as they worked with me in the same shop or nearby, next door, across the way and such. The art of the blacksmith, the potter, those in my own craft areas of furniture making, joinery, carpentry and general woodworking — those who adzed and axed beams, formed massive tenons day in and day out, that sort of thing.

I can’t really describe what it’s like to design a table leg in iron and watch as a blacksmith hammer-sculpts it and then the entire table over the next two weeks or so. I mean, I designed these things to be made for customers from raw steel to hold my woodwork. To see the faces of those buying the commissioned work as a joint endeavour of two diversely different artisans is pure joy! There’s the table, the bed, the lamp and leaf, I mean. If you’ve ever made a dining table to sell for $48,000 you begin to understand that skilled work commands a certain measure of support, yes, but that the art of crafting can be a difficult path to pursue until you catch someone’s eye that sees your true worth as a maker and designer. Another I designed in mesquite and steel, a coffee table, I undersold for $5,500. It was stunningly made with hand-cut joinery in steel, peened-over tenons, drawn-out tapers taking a thousand hammer blows.

The art of craftwork is dying out, not being saved, of course. Who is it that can compete with mass-making? If we say it’s not dying out we live blinkered by our own ignorance. Historical organisations only express what was and never what is. In my 70 years, each decade has shown me that crafts are significantly diminishing year on year, that we see less of crafting work by each decade’s passing. It is indeed unstoppable simply because there is a massive gap now between those that can afford handwork and those that cannot. But it is much more than that. Another gap has gradually caused the great divide and that is the reality of a new generation that has never seen or known the art of it, recognised it for what it is. The generation I speak of never heard the ring of the hammer striking steel, the anvil’s ring that followed the strike by a man’s arm and hand. By that I mean we fail to see and understand the fuller value in the physicality of manual working as today’s microcosm of what once universally supported all areas of life throughout the world.

Through the decades we have seen handwork projected into a mini industrial world as a supplant of an industrial process: think something along the lines of a knitting machine, slip-casting clay mouldings into an inner and outer latex mould for slip-cast pots and castings, or copy-lathe turning for woodturning, and then of course, in my own field, the complete takeover of woodworking by, albeit downsized, industrial machine methods where handwork is literally minimised or even eliminated altogether. This being so, we see deskilling as a more advanced societal improvement whereas the skilled work we once knew and recognised as such, respected, depended on, was the truly skilled work of the masses instead of the now isolated skilled work of the very, very few. Translating craftwork into industrial work using mass-making methods should be recognised for what it is in relation to what it once was and that is simply a means of producing cheap, disposable products to generally at least feed the consumerism as the evolved pandemic in all of us. It also made even more money for the owners of wage-slave workers.

I’m often told by media watchers — exponents and such like — you know, the informed, and then too those influenced by entertainment makers and presenters, that “They’re bringing crafts back!” The sentence always has a cheery, affirming sort of smile warranting the exclamation mark, italics and bold text too. “They’re”, means the government, education departments and so on of course, and not really individuals training on a one-to-one basis. They’re kindly trying to encourage me and think if we just say it and believe this to be the case then it will happen. Of course, “they’re” not. The ‘They’re’ is not that kind of entity. The ‘they’re‘ is more about their bums-on-seats economy only. The other one I hear, after asking me what I “do?” is to say, “Oh, I love craft shows and I love living history museums where they show the ‘old school’ ways of doing things.” I think people sort of hope crafts don’t die out altogether and comfort themselves by somehow being convinced that the crafts are being restored, kept alive. But saying it doesn’t really mean much along those lines at all. It’s surprising how many associate woodworking with the recent so-called green woodworking movement of the latter couple or three decades. It’s nice to sit with friends by a wood fire and carve wooden spoons with a purpose-made knife, an art if you will, very beautiful sometimes, or even set up a spring pole lathe to turn a bowl or a few chair legs, it’s another thing to do it as a way to make a living and especially long term. Reenactment too can be interesting and if well done might even feel more real in the field, so to speak. It does not bring back the reality of artisans making to live by their hands as in say chair bodging or spinning and weaving. Yes, there can and will be some vestige of what once was, perhaps, but crafts can never return as a way of life without a total collapse of globalism, economy, and its bed-partner, consumerism simply because handwork can never keep pace with consumerists and their ever-exhausting demands.

. . . his hammer lay flat

to the anvil’s table where no more

steel formed the art of his hand

for no man came to replace him . . .’

Except for those occasional small pockets of individualism by some less compliant individuals and tiny groups, crafting of every type is mainly supported as a hobby or a highly specialised art form — think remnant, skilled blacksmith replicating authentic ironwork, stonemason and woodcarver restoring buildings and no longer at the beginning of a new cathedral taking centuries yet to build and amongst a hundred more in each craft on the one building. Even then, today, you must recognise that much of this work can at least be roughed out by machines driven by a computer system somewhere along the line and even on a different continent. Perhaps me too, making my rocking chair and other such individual and special pieces. We, crafting artisans, are a dying breed. Very few can work effectively fast and efficiently enough by hand to make a living simply because the drive that drives us changed. In recent years I watched several furniture makers making that spent 50% of their day perched atop a barstool staring at a device. “Fraid this doesn’t get the project from the bench to the customer and the customer rarely likes to pay for a Googler. Even the bijou studio manufacturers of hand tools, woven ware, pottery and so on, rely heavily on production methods and ultra-high prices to make it a way of life. So why lean in the direction of mastering a skill?

Just as cultures around the world have died to the support of skilled craft by buying into mass-made and in most cases disposable goods, so too has the culture of making become obsolete enough to be actually lost. As the art of handwork continues to decline in and of itself, it is most likely that you will not know anyone that makes by using their more long-term, established skill in handwork. Therefore, we will indeed see the finality of artisan making even in those areas of unique communities that might retain some vestige of an ancient tradition. Any craft area that we might see some kind of craft revival, wooden spoon making with bent knives, froes for splitting and axes, will be the result of an individual self-studying an art form for personal interest, self-improvement, etc. As a way of making a living, most to make anywhere near a living wage and those that do are the ones that persuade others to learn from them on a course in the woodlands somewhere. Most are very unlikely to find a market for their treenware, even if one or two of them cand do sell a wooden spoon for £50. The retentive value will be in that personal interest the individuals have for making using raw wood for free from the woodland, spending time there in earthy environs, nature, and not because the public sees what is made as a convenient resource from a local crafting artisan. As long as IKEA sells a solid beech spoon and spatula for £1 and 12 of their meatball lunches and coffee for a fiver, people will keep going to the great cathedral of consumerism. In most cases, I see crafts now continuing on a far lesser level if they are developed as a hobby as a personal interest. People with some level of additional support from family members as main earners and those with disposable income and disposable time to invest in support of their chosen craft. Beyond that, craft has indeed become a lost means by which we make and live. For me, I am just thankful that woodworking, furniture designing and making, woodturning, carpentry and such, have always been my chosen way of life. I do see furniture designing and making alongside those other individual crafting artisans where it is still viable to make and sell pieces of distinctive design and flair to be of creative interest to buyers. Those of us who consider woodworking as a lifestyle rather than anything that could be called conventional as with work that has replaced and displaced craft and handwork. Across from me is a man that makes many types of components for cars. It’s a small compact business with different machines he operates from his computer. He loads the machine with metal blanks every few hours and when he comes back an hour or two later there are the multidimensional components pristinely shiny and ready to ship. He loves the work he does in the same way we woodworkers do. We do it only because we love it and then we can also make income from what we make too.

The important things I see and feel more now is to see crafts as a way out. Woodworking is especially good and doable for this and hand tools have been the most inclusive of all ways simply because you need so little to do it and you can accumulate the few tools you need over a period and end up with a way of easing the pressures of life without a garage full of machines or even one. In its new and fascinating multidimensionality, hand tool woodworking has an appeal that stretches around the globe. Yes, some are highly privileged and assume everyone else either has the same or they just need to work smarter to get them. But the differences across borders are often chalk and cheese. For me, hand tool woodworking is healing for the majority who do it, it’s therapy for others and then recovery from many different types of abuses. For some, maybe with carpal tunnel syndrome, those with autism, its alternative way of working that gives a measure of pure relief and so too for those with jobs that bore them to tears and are filled with tedium. Listing the changed reasons is massive, massive. It caters to shifts in our ever-shifting culture to pave a way to betterment. My reasons too have changed. As a perpetual maker, I began to shift, not from making but to expand in my making to teaching and training, writing, drawing and designing. I never abandoned making to teach and make videos alone, I simply added work I believed in to expand my vision and to make my craft as inclusive as possible to men, women and children with and without struggles of a million kinds.

I lived my early life on a farm. in the village there was still a village blacksmith and carpenter. The latter was semi retired. But te blacksmith made his living from local farms in the main . He was an interesting character as he had a false hand. He did ask me as a teenager to become his apprentice, often wondered if I would have made a living, but took another path. The person who eventually replaced him spent too log in bed and didn’t last long. I guess I was witnessing the “death” of local craftsmen, but at the time I didn’t realise it.

That’s interesting. I feel blessed to have been trained as a journalist and editor before new technology was introduced by Eddie Shah and Rupert Murdoch, when the typewriter ruled and shorthand was enforced. I am one of a small cohort well trained in the old and the new. As I result I have the ingrained disciplines of punctuality (in all ways), deadlines and consistency, yet can embrace the opportunities of elaborating faster with better reader interaction.

The problem is over population. As I get older I see more and more people, with those people comes a dwindling of resources, and increase in consumerism, increase costs, and above all else competition to make a meager living. It is unfortunate that the profession that I love will not support my family the way sitting behind a desk producing nothing will do. I wish for things to be different, I do not wish to be merely a hobbyist but to allow my creativity and feeling of accomplishment rule my day. Looking back over my career I feel a sense of emptiness, the only pride in accomplishment being that carved out of my free time. Slave of the masses.

I doubt your right to say overpopulation is the issue. You would better say the Industrial Revolution was the most key factor ever in history and that technology takes the whole a thousand times faster while developing nuclear fusion as the perfect answer to cheap energy. How amazing is that? The plastic bag was an amazing development of a Swedish engineer Sten Gustaf Thulin in 1959. Supposedly they would save the planet by reducing the need for paper carrier bags.I don’t really know. Being a maker is mostly a decision to do it. Just not everyone can be a maker because if they were we would swamp the world with makers. Maybe it would be better to place higher demands on industrial makers to have ethics and pay living wages plus some to their workers rather than espousing their cheap tables and chairs that last an average of seven years. Maybe curtail imports and exports to dismantle globalism, throwaway goods and such. If someone chooses to not sit behind a desk and make then they could do it. They might be down to a smaller house outside a big, overpopulated city, using a bike more and a car less, maybe own just one car too, and then eating less rich diets and such. Lots of options all around, I think.

I agree Paul. I think over-population is an easy target. We’ve created a system that is fueled by growth – both economic and human resource – and fueled by fossils.

If you look at the trajectory of fossil fuel energy use versus population growth, the two correlate strongly. I don’t see us ever replacing the energy density that fossil fuels have provided, and predict a contraction of population as fossil fuel use declines. Together with the effects of climate change, I don’t think we’ll ever have the political and social conditions to effect nuclear fusion before we collapse under the weight of our own hubris. I predict that in a few centuries, we will see the makers of old rearing their heads again. The skills that we nearly lost, re-learned. It’s not just woodworking, its our very senses. Identifying plants, smelling danger, feeling the grain direction etc. The things that used to make us humans, that have been replaced by an illusion of progress (surely these losses are dumbing down?) as we’ve become a domesticated species. I think it’ll be a difficult next century either way.

Twice recently I have been tempted to watch TV programmes allegedly based on mainly hand woodworking. Both have instantly shown that the producers and workers have completely lost the concept of real craft and distorted the understanding of any viewers who unlike me continued to watch.

I am old enough to have been at school when there was still an attempt at teaching wood and metalwork. Sadly for me I was bold enough to point out the horrendous design and waste of exotic wood for the table lamp I could never have taken home to show my parents. I was banned from the woodwork shop for the next seven years!

Even with a low income I have never bought a single piece of throw away furniture but know that few will even value those hand crafted pieces made over a two hundred year time span as fashion dictates an ever changing look after another trip to landfill…

The rebuild of the Cathedral of Notre Dame is an interesting exception – which certainly doesn’t disprove anything Paul is saying. But a horrific fire has led to the need to rebuild a large timber structure and they elected, after a fight about it, to rebuild in timber in the “original way”. The devil is no doubt in the details, but they are rare in having a timber framing organization committed to hand tools only and skilled in the old ways of building with timber: Charpentiers sans frontières (Carpenters without Borders). If we’re lucky, the world will get an amazing timber roof structure similar the old one which due to its massive size was known as The Forest. A timber structure to impress over the next few centuries. I really hope someone captures this work in video. Thanks

The French have some very sensible attitudes in many things. I only lived there for a year, but found that – bureaucracy aside – they have a sense of heritage.

And to check out some old timber frames and see it being done – check out this tv show: shows you round them, does lovely drawings of how they were put together and shows some newer ones being built. Lovely stuff.

Fred Dibnah’s Building Of Britain

S01E03 The Age of the Carpenter

I believe in what Paul is saying about the decline in the desire to do hands on artisty. The element missing is the desire of the parents to engage in an activity that they really enjoy apart from the demands of the every day demands of the work place. For example, if mom works, she’s too tired to bake. If she doesn’t bake her children don’t reap the benefits that result. Eating fresh bread and knowing how to measure the ingredients. The same holds true for the father. After dinner, there is no activity that would stimulate the art forms. Too many distraction. After living that kind of life style, retirement has left me with time to do things with my hands that my mind would have in reality. A turned bowl, repaired furniture to a stronger fix. The down side, my children are not working with me and learning new and exciting things this life has to offer with hands on activities.

This is some of your finest writing. I love the indignation of this.

When the pandemic was in full swing I walked past groups of young people on the hiking trails talking about cooking for the first time. These people evidently never cooked a meal in their life, all they did for sustenance was fast food take out. Someday I suppose food will be printed out and people won’t know the difference. I’m guessing they probably didn’t like what they cooked because it didn’t have all the yummy chemicals like the other food had.

It’s not cost efficient for someone to go through an apprenticeship anymore. The way things are made keeps changing as technology improves. I had five or more careers in my life, all of them are obsolete now and my four year apprenticeship expensive as it was is not much use today.

So yeah, we will never see groups of tradesmen bashing out mortises by hand again. It will be left to the artists. Having said that I wonder how the rebuilding of Notre Dame is going, there has to be some skilled artist/ craftsman working on that!

Indeed, Tom. No doubt. But that knowledge is of little consequence and even less consolation if we are realistic. Another cathedral to look up at and into will impress the tourists in the coming decades I am sure, and of course, that will bring in revenues lost maybe. What’s more lamentable to me than the loss of a building for a few seasons is the very permanent loss of our crafting cultures worldwide. I mean, we are talking extinction levels here and that in my mind is as tragic as other extinction types. Despite the rebuilding of a cathedral, and whereas there may be an odd cluster group in different trades here and there, remember that there were hundreds of thousands of artisans a mere century ago and where are they now? Well, they’re all gone, dead and buried, along with the hidden skills. Oh well, that’s progress I suppose. You just can’t stop progress, it’s said.

Oh, and my post was a bit more than, “So yeah, we will never see groups of tradesmen bashing out mortises by hand again.” It was to get people to think more deeply about what we’ve lost and to perhaps counter people saying, “They are bringing back crafts again.” as though that’s really happening.

A pair of monts ago I showed a friend (he worked as woodworker some time ago) the pics of a wooden box that I made for my Record #778. That box had my first hand-cut dovetails (really not bad to be the first ones, I must say). This was his comment: “very good, but you know that dovetails are made by router today, don’t you?”

I buy my wood in a woodshop that makes work for clients and sells lumber too. A shop full of machines, of course. Good people, but only one of them knows how to work by hand; the rest of them are men who uses machines for everything. I bought some big scraps of beech that were behind the gigant bandsaw and showed the pics of my PS router plane to another employee. He didn’t recognize the tool nor knew what its utility is. If you look around on that shop, you cannot see handtools, only machines. Chopsaws, planer-thicknessers, drum sanders and a really big vertical disc saw. They know of my amateur handtool woodworking. Some of them see my “work” with good eyes, buy they always end saying the same: you cannot achieve the quality and precission of the machines with handtools; you cannot be in the market with handtools; that kind of woodworking is lost forever.

Anyway, I think that almost nobody would pay the value of that kind of woodworking. Part of them cannot pay it, part of them don’t want to pay it. People want speed, inmediateless, changes, and some of those who would pay the handwork by its value cannot pay it. Quality, durability and things like that no are things that mind people, unfortunately.

(Sorry for the errors in the text, if they are. English is not my first language).

Hi Paul, interesting thoughts. I recently built my own forge from scratch, mostly recycled scrap metal I have collected. I will fire it for the first time in the next couple of weeks, your welcome to come and try it out as your not that far away from us? I’m sure you could easily turn your hand to black smithing.

That’s a very kind offer, Elliot. I would that Sellers’ home had a space for a home forge but not sure my neighbours would appreciate the anvil’s ring like I do.

I stuck some magnets on my anvil and they dampened the ringing some. The one stuck under the tail seems to have the most impact to me.

This is a very poignant and insightful article. It takes an excellent sense of perspective to see one’s endeavours in the bigger context of historical trends. I suspect it makes a lot of us reflect on our own path in life.

I have become interested in the Social History of work and industry, and have read a couple of interesting historical woodwork books lately. One particular book, “The Joiner and Cabinet Maker” details the apprenticeship of a 19th century apprentice Joiner. It’s a very interesting read. I would be absolutely fascinated if Paul wrote the equivalent for a 20th century woodworking apprentice, having first hand experience of earning a living from his skills, and then experiencing the tectonic shifts towards consumerism and the decline of traditional hand skills. The skills, the relationship between the (presumably) men, the small things that stick in mind, etc. There’s at least 2 books in there.

I would love to compare and contrast, and I suspect in a hundred years there will be a few people like me who would do the same. I think the historical record would be grateful, and it’s as necessary to capture the human aspect, the social and industrial history, as it is the skills and knowledge.

Paul – I presume this has been suggested to you already? Is it something you would consider? There’s clearly an audience out there, both now and (presumably) in the future, who would very much appreciate the voice of a participant at this transitional point in history. I imagine you have a much bigger list of things you’d like to do than time to do them in!

Thanks.

I have three manuscripts well underway. One is my life’s path to where I am today, the good and bad of it, and the other is a working man’s perspective on why we work rather than the vacationist-reporter’s perspective after dipping one’s toe in and writing an expert’s experience on why we work with our hands after spending a few weeks or even a privileged year privilegely working manually (for a change) but ultimately going back to writing and editing as some kind of self-appointed person in-the-know of it. So, yes, I am hoping that these will be of some value for those going beyond the dipping of toes in. BTW I do not consider amateur woodworkers to be such people. They have set themselves the task of becoming masters just as I did and that, I think, has become my emerging audience. I would most likely trust those continuing my work to the hands of amateurs and never the so-called professionals.

Great to hear, thanks very much for responding. I look forward to seeing their release, as I expect others will.

I am intrigued between the similarities in your life and the transition the author experienced in “The Joiner in Cabinet Maker” (a working joiner), as the country entered the Industrial Revolution. The change we are seeing with modern manufacturing and technology is similarly as profound.

PS I’m not a salesman for that book, although it may read like it!

Just transitioning to hand tool woodworking from accounting job. Feeling doubts along the way but trying to stay motivated. Making and fixing many errors when doing cabinet for first commissioned piece. It already taking a lot of days and hours which is bit diacouraging. What helps are Paul’a old stories about the hard time he had when he was selling some of his work. Also, big difference and learning curve to do things for demanding customer and not myself. Had to watch some Paul’s videos once again and pay atrention to the details. Just sharing…

I’m currently doing exactly that, building a timber frame workshop with hand tools. Sawing, chiseling and planing a scarf joint in an 8 x 8 piece of douglas takes me a while but the work is as rewarding as the result. It’s almost like a dovetail, needs the same TLC to get it right.

A mate of mine (proffessional builder) helped out a couple of times. Last time he talked about bringing a chainsaw next time to speed things up. He used a circle saw on some tenons, the shoulders of which now need to be squared properly. He didn’t really see the need as ‘it would fit anyway’. I guess he’s used to working to the clock while I’m just an amateur who learned that it’s not what you make, it’s how you make it that counts. Don’t care if it takes me two years.

I showed him how I work and he was amazed by the sharpness of my chisel (that needed sharpening) and how quick I sharpened it on 3 diamond stones and a strop. Some saws, chisels, a plane, a mallet, bit and brace an some measuring/scribing tools is all you need to build a timber frame. And some sharpening tools of course. I have yet to meet someone who appreciates what I’m doing. In the mean time I enjoy being in my bubble, knowing there’s others like me out there, somewhere.

Mic

I think craft evolves, but will never die. Stonecarving became extinct as a craft before woodworking, because people didn’t value the product as much as they used to. It’s a sad reality. But with the decline of those comes an increase in other crafts – specifically I’m thinking of electronics, programming, and the “maker” movement. It’s apples-to-oranges, for sure; “makers” do not use the same skills, tools, mindsets as a stonecarver or woodworker. But I still think the term “craft” applies. The tools and materials are accessible to everyone, the products are arguably very useful, and some will continue to hone their skills and reach a level of proficiency that they can make a solid living. And someday, they too will fall victim to industrialization – auto-coding, automated manufacturing – and become quaint reminders of how things used to be. And then something will take their place.

I think every area of industry adopts archaic terms like craft, crafting apprenticing and so on, mostly to give the illusion a more complete and acceptable face. Hence the switch from the long-used and accepted term woodworking machines to power tools, coffee crafters in chain franchise cafes and so on. Reality is that someone working at Starbucks and Costa coffee learns their so-called but not really ‘craft‘ skills in about half an hour and becomes a ‘barista‘ when they can twist a couple of steam valves and can press a button or two. The skills in EVERY field will always be dumbed down at some point to replace skills and craftwork. We can indeed delude ourselves by using the terms but an orange is not nor will it ever be a banana. So, my question remains the same: do crafts continue to gradually develop in a bettering way, as in evolve, as you say, or do they more likely degenerate along with the culture surrounding them. Woodworking reached its zenith 200 years ago and I have yet to see the skilled work exemplary in millions of pieces paralleled anywhere in our world today. I mean, I have not seen much to come close to matching what was once common on every continent in today’s craft world except once in ten years in an isolated case. We will soon need to accept AI replicating by copying what a man skilled with his hands does, and instead of admiring the creator of the machine, no doubt a noble developer, we will admire the outcome of the machine work. Oh, and crafts will die. They have to you see. It doesn’t take too much brain power to look at what we have now and compare it to 100 years ago. Just take a saw handle alone.

“ or do they more likely degenerate along with the culture surrounding them”

Well put. That statement is very succinct, very cutting, and hard to argue. Makes me appreciate even more the time and effort to (poorly) build something with these methods. I hope I can pass at least some of it on to my kids.

One of your best and most inspiring ‘philosophical’ posts, though the ones I enjoy the most are the wonderful examples of the master/apprentice relationship in your stories about George. ‘Inspiring’ yes but a very real, necessary and dire warning. We seem to have forgotten that the purpose of any tool, machine, computerized or whatever, is to make the work easier, which requires skilled usage, rather than to do the work for us, which is how it seems everyone views machines. And with skilled usage, to realize that so many machines are actually designed to do the work for us, and so the use of them should be rejected in favor of skilled hand usage.

However, I was minded by your comments on the skilled (or otherwise) usage of coffee machines of a conversation at one of my favorite independent cafes many years ago. I noticed that there was a new young person there and found out that he had recently started after working at one of the chains. His comment was that he had realized that he had to completely forget everything that he had been ‘taught’ at the chain and to start again under a properly skilled barista. They say that it can take six months to fully get to know your coffee machine and so be able to pull a consistent and perfect espresso every time.

A similar story from here in Sheffield was to be told by retired highly skilled workers that the worse thing that happened to the industry was the introduction of six month training schemes back in the 1970s, instead of proper time-served apprenticeships.

Another area that dismays me is in artistic expression, where an otherwise fine study is spoiled by the craftlessness of application, and worse still that some ‘artists’ seem to glory in the fact that their work lacks craft.

Our society has indeed forgotten just what ‘skill’ is.

Here in the US, a contributing factor may be the class divide between blue-collar (practical/physical) and white-collar (office/lab) occupations. Emphasis on the latter soared over the past few generations as the image of the tech mogul soared, the economy shifted, and building/repairing mechanical and structural items became something the upper class only wanted their kids doing as a fallback if college was clearly not a good fit. There are probably a lit of kids being pushed into –and dropping out of– higher education who would be well served by the “technical high school” path, but that gets looked down upon as a poor second choice.

We have to respect craftsman if we’re going to recognize, understand, and respect craft. And we need to be more open to the idea that people’s interests change and do so at different rates, and find a better way to let people move between these two domains without as much social penalty.

Tangentially related: It may be worth noting that the computing industry is actually starting to look more toward a craft and apprenticeship model; programming is something kids have been learning earlier and is no longer considered so esoteric a skill. There’s still value in advanced study, but it’s starting to look like the idea of there being a technical high school path for programmers — with later opportunities to get the deeper background — might be entirely viable. Though of course part of the reason companies are looking at this is the hope that employees without college debt might accept lower wages. Still, that might cause some societal shift back toward better respecting those who don’t have formal degrees.

Hi Paul. I met you a few years ago in Eastleigh bus station when you were tracking down a manual pillar drill. Despite having a father who built his own house and a step-father who was a skilled carpenter/joiner/cabinet-maker, I was always encouraged to use my books and brains, not my hands. Apart from putting up a few shelves and assembling some flat-pack furniture (which have never fallen down or apart) it was not until I approached retirement that I discovered the joys of working with wood by hand.

At the age of 73 and in not so good health, I am unlikely to achieve the standards of quality of you and other craftsmen but, as long as everything I do is a little better than my previous attempt, I am content.

Possibly the most rewarding was making three matching wooden bowls before I bought a lathe. I do use machines when I do work for a friend’s business but there is much more satisfaction in producing something with saws, chisels and rasps where you can feel it taking shape under your hands.

I should know by now not to have a glass of wine before reading your blogs. The piece about the blacksmith had tears rolling down my cheeks.

Myk

“For me, hand tool woodworking is healing for the majority who do it, it’s therapy for others and then recovery from many different types of abuses.”

Healing. Therapy. Recovery. These words are what resonated with me the most from this blog post. This is how I view hand tool woodworking. I have machines and power tools. I can’t use my machines right now and the power tools I have access to are modest at best. I live in an apartment where the walls are so thin that you can hear people’s conversations. This means that even my power tool usage is limited. Therefore, I am relegated to using my hand tools as my primary means of woodworking. This is both relaxing and frustrating at the same time. I want to make things faster so that I can get on to the next thing. This is frustrating. I could use my power tools and make all kinds of dust and noise. That would frustrate my neighbors. I figure it this way though, what’s the big hurry? Why not take your time and do thing with care and thought. This is the relaxing part. It still gets intense, but not like it used to when I was first learning.

With the decline of industrial civilization, hand tools are going to make a comeback. But, yes, the perishable knowledge that we crafters have, needs to remain alive.

Hi Paul,

It’s a sad story your telling. I’ve been a blacksmith here in the U.S. for fifty years and now semi retired spend much of my time teaching the younger generation the craft. Many of them of course won’t pursue it as a means to make a living but I find that enough do.

They may not always be forging the objects of time past but they are using the same tools and methods from centuries ago to reach their chosen end. Perhaps they not making for the local cathedral or carpenter but they are still making. In their work I still can see the drive and dedication to do the finest work possible. I only see that what they make is made to answer the demands of what the customer wants and can also still be crafted at a profit by hand.

Over the course of my career I made reproduction hardware for museums and private homes. When that work waned I forged tools for the machine tool trades, then on to fine railings and estate gates and on and on as the times and the market changed.

I see my new younger smiths doing the same. They not be making what I made but they are making. Using and learning the skills that have been used since the beginning of smithing and they are keeping the craft alive.

When I started smithing it truly was a dying craft. Today there are more full time smiths than have existed here in a hundred years. Many of them more knowledgeable than the remnant smiths of a lost craft that existed when I stared.

I’ve watched you now since your beginnings here on the internet, mostly because of your efficient and skilled way of working. A workmen like manner that only from dedication too and love of the craft and the work. But I’m afraid this time I’ll have to disagree with you. I can’t from my perspective on this side of the pond throw away the hope of craft surviving.

I’m not sure that you got the point, Dick. Being a realist is not always easy, I know. Sad though it may seem, crafts have and will continue to die in the true identity of makers making a living from working with their hands. I take nothing back. I was discussing all crafts on a worldwide scale and not just blacksmithing in the US. You have to think from a personal perspective on a local level to begin with, yes, I accept that, but then you must think nationally. I lived in Texas for 23 years and traveled its length and breadth extensively and blacksmiths were simply not anywhere to be found in almost any town and city. Of course, there is farrier work still around for horse work, that will always be, but most farrier work, skilled though it is, is not blacksmithing whereas blacksmithing often included farrier work. Horses will always need showing and there is no robot yet to replace that human touch working with a horse that doesn’t want a set of new shoes. The days of the blacksmith are indeed numbered in that case. Also, I was addressing craft diminishment as more a global issue on whole continents and not just the USA.

Interesting you should say that Mr. Paul.

Some 40 years ago I was completing my higher education. The

Professor asked our class of about 40 students who knew what a farrier did. About half the class raised their hand. Then we were asked what was a blacksmith, two of us raised their hand. Then he asked what the difference was, I was the only one who knew. The Professor told us to go into the trades – plumber, carpenter, electrician as these were dying out and to forego our higher education.

In the ‘70’s, I owned a mare who could not be fitted with the pre made shoes and had to have them made. Our farrier, who was also a blacksmith, would come at dawn, start his coal fired forge and the beautiful ringing would start. Even back then, it was a skill hard to find. Someone who could take a bar of metal and turn it to a custom shoe, rather than trying to force fit a shoe made by machine. Though a young man in his 30’s I suppose, he worked quickly and efficiently. His calm demeanor kept the horses calm. My hot blooded mare would rest her head on the poles that made up our arena and be mesmerized by his working. After all the horses were shod, Mom would serve him up a nice lunch as his forge cooled down.

On another note, we went to a large craft show back in October. Several of the custom furniture makers were bragging shall we say on their handiwork, save one. I like to talk to custom furniture makers and see what they’ve used to complete their product. All but the one used either polyurethane or a urethane finish and most were spotty at best. They also used power sanders of some sort and they didn’t get all the dust off before they applied the finish. The one artisan who didn’t, used hand tools for the majority of his work down to finishing with a hand plane and card scraper to get the beautiful to feel finish with shellac. His desire is that in 100 years or so, when and if the finish needs to be repaired, someone will have an easier time and not destroy that which only years can provide.

I don’t mean to be flippant but perhaps you weren’t looking in the right places.

Check out this link, a late friend of mine was a professor there. https://acba.edu/. I do realize you weren’t just talking about the USA but if in the world of craft it is growing somewhere then it is not dyeing.

Is our teaching this next generation just for our entertainment or is it to perpetuate the crafts?

I’m not really sure how to answer your question, Dick. Again, on a global scale a lone college will do well to cater to the need for skilled artisans on a localised scale such as within the pockets of countries like the USA. To say that what’s being offered in an odd college course here and there in different countries compares to a hundred and two hundred years ago with bona fide apprenticeships in every craft trade in every town, city and even the very smallest of villages as was the case in Britain for sure is just unrealistic. It’s a question of opening our hearts to the simple reality here. Maybe this will help: in the 50,000 towns, cities and villages throughout the United Kingdom of Great Britain a village would have at one time had a blacksmith, a couple of carpenters, perhaps a furniture maker and then too a dozen or more other crafting artisans such as basket makers, a couple of spinners and a weaver. In these pre-plastic days these crafts would have been essential to the support of life and baskets were used for every area of country life for harvesting, transportation, storage, etc. Even at this minimal level, that means that there would have been 500,000 apprentices learning from a few million masters of their crafts across Britain alone. Of course, in a city like London, Manchester, Glasgow, and many a dozen other sizeable cities, the number of skilled artisans and businesses would be many a hundred times greater. I might suggest that London alone had thousands of skilled artisans in and surrounding its city. Each artisan or group of three or four of them would have had several apprentices at different levels or stages in their training. In my apprenticeship, alongside six skilled joiners, there were six apprentices at various stages in their training one on one. So we see, even a century ago crafts tied to income would have been thousands upon thousands of times greater than a college here and there providing a college course which in no way can ever compare to an apprenticeship working and making alongside a gifted crafting artisan eight hours a day. My article was purely to highlight that crafts are indeed dying and indeed they are. Very few college graduates will continue in the trade if indeed they even get a job at the end of their three years. I know graduates from a local furniture college in the centre of Oxford where most of the graduates, having spent £30,000 on their course, are now pumping MDF panels into and through machines most of the day. College courses have never nor can they ever replace the structure of an apprenticeship working alongside a skilled master craftsman and woman. I realise my opinion disappoints you but if I believe any different I would do the next generation an injustice. Currently, I have three apprentices at different levels and then too of course many hundreds of thousands online who might never be able to apprentice any other way.

Also, I do think that apprentices would do very well if they were to take college fees and pay for their education with an artisan. They would gain twenty times the knowledge, get full training on the job and could dispense with the piece of paper called a diploma or an NVQ. It would reduce the cost on the taxpayer too and the teachers of courses could increase their skills in their craft to become truly competent artisans. Just an added thought. Oh, and I have a friend in California who applied for woodworking course at Colleg of the Redwoods and the instructor told her she would be better applying for a “more appropriate course”. I think we can guess what that means. So she has been distance learning with me for the past eight years.

many thanks for these thoughts. they’ve got me thinking of my own working life as a woodworker, which I took up after a career in IT

There’s a saying I heard: “you can make anything with hand tools except a profit” – which, sadly, is true for many people

I’m lucky in that I don’t need that much money to meet my basic needs, and as I’m happy at work (barring the occasional ‘difficult’ customer!) I don’t need expensive distractions – I have a life rather than a ‘work-life balance’ and that suits me

I’ve been lucky in that I have a couple of good customers who buy and sell furniture which they pick up cheaply at auctions and often needs repairs or refurbishment – and you simply couldn’t do that without skill in hand tools. the chap I share a workshop with has also realised that he can whack a groove into a piece far faster with his Stanley #45 than going through the rigmarole of setting up his router table, so there’s now a place for hand tools in his work

another job I get on a regular basis is refurbishing tabletops. this is a cinch with a combination of card scraper, scraper plane, my trusty Record 4 1/2 (set up for very fine smoothing with your youtube guidance) and a bit of elbow grease. other chippies would use a belt or orbital sander but my experience is that customers don’t want their old table to look completely flat and new, just more usable and this isn’t really possible with machines alone. I can sort one in an hour or so (often in the customer’s home, which cuts down on ‘faff’ and the possibility of damage during transport) and people like both the result and the process

(I also make bespoke storage solutions and design them in 3d: the last means the customer is involved in the design process as the drawings are much easier for the lay person to understand than a standard technical drawing)

people are definitely getting tired of the ‘throwaway’ culture and the poor quality products it favours. maybe it’s a niche and made possible by my own circumstances, but I can do ok and not price myself out of the market by using hand tools. I think the service aspect plays an important role – crafts is not just a product industry and I always invite my customers to my workshop, which many enjoy – in particular because of my hand tools and the quiet atmosphere. I have a bandsaw and table saw but it’s not a ‘machine shop’

anyway, that was a far longer post than I’d anticipated, but I think that with the right approach it’s possible to ‘deindustrialise’ your working life to an extent

My take on this is different. “you can make anything with hand tools except a profit” will be said by someone who can’t hack it and doesn’t want you to either. I can make a rocking chair in five days that sells for £2200, that’s enough. I have made a profit enough to support a family of four children on my single-income wage. I did not get rich but I was content and all of my work was woodworking and making furniture.Oh, and I am talking 57 years of woodworking to date, by the way. Customers are out there, you just have to pitch to that audience.

I’d love to be able to sell a rocking chair for £2200 but I’m neither Paul Sellers or Sam Maloof – your brands help you find a market at that level, and while I could make something comparable in a week or so (perhaps not quite at your standard or his, but not bad either) I operate in a different market and I don’t have the name recognition you enjoy (and, in my opinion, fully deserve)

and an example: the local auction house recently sold a beautiful handmade traditional carver for £20 to a friend because there were no other bidders. while people can get bargains like that, or similar old pieces for less than £100, in the area I live in (rural West Country) then even a £500 rocking chair would struggle to sell

don’t get me wrong: I use hand tools all the time because they’re simply better. you can’t get the finish a well-tuned smoothing plane gives using a machine approach. it’s simply not possible and my customers know and appreciate that

When I sold my first rocking chair for $6,500 25 years ago no one knew me or who I was. They sold regularly as did everything I made at that time. I think this was America. generally, they are highly respectful of craftsmanship of any type as long as it is good. The Brits are less so, in my experience. When I came back to the UK in 2009 a man walked into my workshop, saw a rocking chair and said, “How much is the rocking chair?” I said, “£2,200” and he left. I carried on working. I had built that and my other pieces speculatively, to sell if someone saw them and wanted to buy them. An hour went by and the man who asked the price of the rocking chair came back and asked if it could be delivered and how much, I said, “About £200. He said, “I’ll take it.” and he gave me a check. This man and 90% of my customers throughout the years of my working had never heard of me before walking into my workshop. I think it is all too easy to have a reason not to do something but I understand that it does take courage to put a week’s work into something that might not sell straight off. No one I ever knew had an already-established “brand” so it’s not good for anyone to hide behind that one either. College tutors focus on rubbish like that, telling students they must become a brand. Nonsense. That comes when you do good work. I have made and sold all through my life without a “brand”and it does get easier. The important thing is to let your work speak for itself. It will.

As a child I visited the local blacksmith to see him shoe horses, repair gates and make car springs. I did fancy the job but my slight frame would not have been up to it. As it was I spent my working life repairing aircraft, so metal work of a kind. In retirement I took up woodworking, having done it at school.

I’m very conflicted reading this post. I agree the craft world you describe is indeed dead. I grew up in a neighborhood where we had bakers, taylors, butchers, plumbers even doctors and dentists plying their trades to the locals who made up their clientele.

Most of those trades still exist in a different form now, the bakery I went to as a kid and into adulthood is no longer in existence now it’s the supermarket who supplies my bread unless I decide to make it myself. There are plenty of plumbers but they don’t solder copper pipe now they connect plastic pex pipes instead. I’m not about to debate the relative merits of copper over pex that’s not the point, things change we decide for ourselves if the change is for the better or not.

In my professional life I was a skilled optical machinist (engineer I think you would say) and I saw things change dramatically in the 40 or so years I worked. In my first job we had all “manual” machines lathes, milling machines, grinders, drill presses etc… . The tool makers would design and make fixtures which were setup on the machines and the less skilled workers would produce parts using milling/drilling fixtures. I spent one winter standing at a drill press 8 hours every day drilling and tapping holes in the lens box assemblies used in photo printers.

I eventually started working at a different shop where I became the supervisor. We started with a fully manual shop and eventually added digital readouts then CNC machines. Before the CNC machines I couldn’t understand how our venders could produce parts and sell them for less than we could make them! Eventually we bought a CNC lathe and milling machine and I understood. The first piece took as long or longer than making it on manual machines but subsequent parts were much faster.

Eventually even programming the machines was “automated” with software such as MasterCam or Fusion 360. I started using MasterCam to program instead of writing the programs in Notepad and uploading them to the machines. For multi axis work it was much easier and more accurate than developing fixtures for secondary operations.

The last 10 years of my working life I taught at a community college level in an Engineering program for Deaf students who wanted a job in the machine trades. It was my opinion that a solid foundation in manual machining was necessary if one were to be successful with automated processes. After all tool makers are still the most skilled machine workers and there is still a very high demand for their skills. Still if I’m honest I have to say anything that can be done on a manual machine can be done on a computer controlled machine so even tool makers must have modern skills to be employable. Hence I steered the program I taught in towards more not less CNC work with much more hands on in that area with less emphasis on skills with hand files. If I were still teaching I would recommend adding multi axis machines, live tooling, 3D printing and so on to make the students more employable.

All those changes over 40 or so years were driven by the design engineers who had access to sophisticated engineering programs which made it possible to design things which would not have been easy or even possible with pencil and paper.

It is absolutely untrue that an automated machine requires little or no skill to operate. The idea that modern machines require no skills is not true and is in fact insulting to the many people doing that for a living. It is true that there is a hierarchy of skills but that has been the case forever. I am sure that in the times Notre Dame was constructed there were the skilled stone masons and carpenters and those who moved, held and hoisted the stones and timbers but never became masters themselves. Just as I drilled and tapped holes for a very boring winter I’m sure there were some during your apprenticeship who simply didn’t or couldn’t advance in their trade.

The trades were never something everyone did but the very selective few did. You are a very highly skilled individual who I respect and admire. You like me have lived long enough to see your world change better, worse I can’t answer that it’s personal. I think people our age have been seeing major changes since the time of flintknapping and I doubt we all liked what we saw.

Since retiring I have moved in the direction of hand tool use rather than machine use in my woodworking. I can’t imagine why anyone would want a CNC router yet I see them advertised in every catalogue I come across. As a hobbyist I have no use for a programmable machine, if I never program a machine again that’s fine with me but I’m not trying to compete with someone selling things made on a CNC machine.

You may be right craft work as a living might just be dead but people will always be interested in baking their own bread, sewing their own clothes, growing their own vegetables and making their own furniture. I can certainly make an $8000, dining table but I cannot afford to buy one from a skilled maker. I know people who are skilled artisans, woodworkers, blacksmiths, painters but I can’t afford their work.

“You can make anything with hand tools except a profit” will be said by someone who can’t hack it and doesn’t want you to either” seems really harsh to me. You may be among those exceptional people who can indeed make a living with only hand tools, but how many of those 57 years of wood working were exclusively hand tool only? The written word is easy to misinterpret without face to face communication. I do not mean anything negative by my last statement. I think there’s room for everyone and that the skills we develop be they hand or machine are all equally valid.

Blah, blah, blah.

It is true, the only way for craft to return is to remove the complete system of things we now live in. Period. But replace it with what?

I’m not sure why so ill-mannered. Where and when did I say bring crafts back? Who suggested replacing it with anything more than we have. I have no issue with everything as is. You made it blah, blah, blah by stating I said something I didn’t. I wonder why you did that?

One issue that gets ignored is how quick craftmen of the past were. A chair spindle turner would produce a gross of turning in a 10hr day using a pole lathe, about one every 4 min. Admittedly, probably the end of a mini production line (I assume) with timber billets being cleaved with a froe, then trimmed to an approximate shape using a drawknife. I doubt few could match that level of production, but when paid by the item, speed becomes an essential part of the skill.

Hi Paul,

I recently discovered a love for hand tool woodworking but the biggest challenge for me right now is lack of space in my London flat to set up a permanent bench.

Have you thought about covering the topic of portable benches? Something strong and stable for hand planing but can be folded up and put away afterwards?

Putting it in writing it almost sounds like a contradiction but I am working on v3 of such a workbench, having learnt some very important and expensive lessons from v1 and v2!

Would love to hear your thoughts as I’ve not seen this challenging situation covered much.

Cheers

Most of my early workbenches were recycled chests of drawers – would that be possible? The prototype workmate was designed to fulfill your requirements, but are not great for heavy planing, you really need weight to keep it firm, I guess that one hinged to a wall is not possible. What about a cover that makes one look like a piece of furniture, or isn’t there space for that?

I don’t have a chest of drawers and as you say, workmate is not great for planing. Too many compromises involved with it so I am trying to make something I can put away when not needed. This is something I am working on after my regular job and would rather not leave something dusty and messy out all the time

Hello, Not an easy fix. I can see how hinges could be used to anchor the parts to my standard bench and then bols through with wing nuts and such. Not too instant but not too bad if you get a day or two’s work from an assembly and then stow it. I have had workbenches hinged to walls where two leg frames swing out from a fixed position on a wall and then the top drops down from its hinged position on the wall too and locked the legs in place. Very stable and consuming very little space. Not pretty but reallynquite tidy.