Buying Your Future

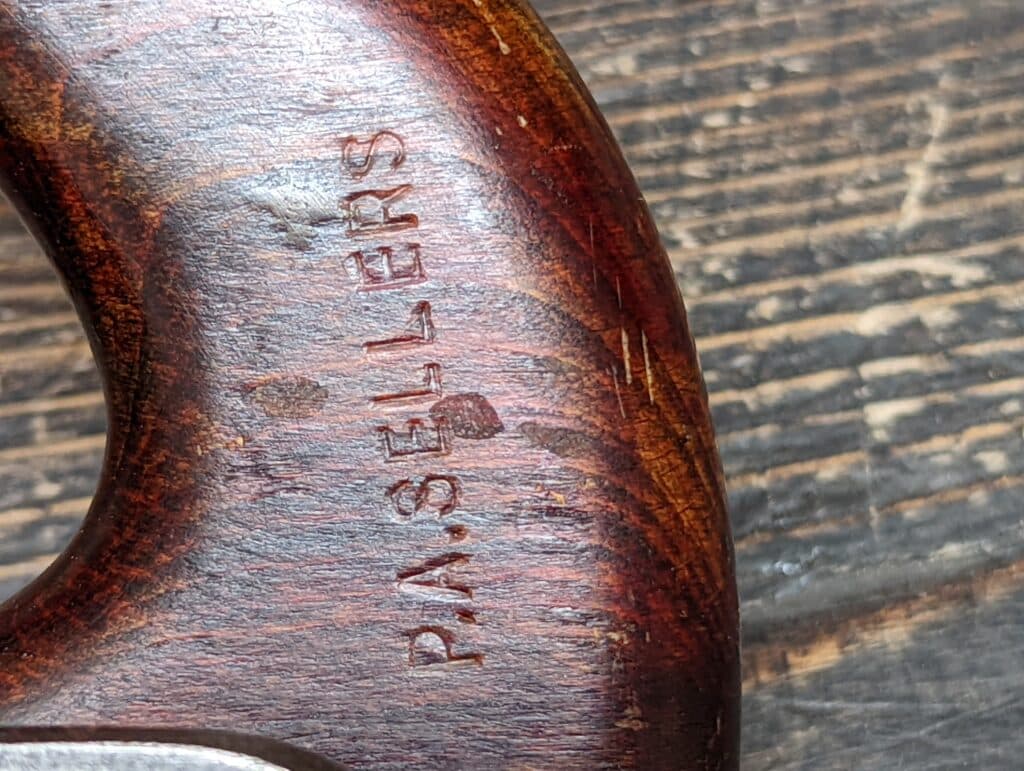

It seems such a small thing, a simple thing.

Not worth too much, even, but it’s yours.

You bought it with a whole week’s wage.

It cost you something, you see, that plane.

I was 15 back in 1965 and it cost me a week’s working in a wage.

When you buy your first hammer, a bench plane, a square and a spokeshave,

aged 15, you don’t know that you’ll be using them, day in, day out,

every day of the week for 57 years.

You took a whole week’s wage to buy each one of them,

think you spent a lot. Too much!

And then you look back, see the beginning, recall the days you spent that week’s wage

and you just swell inside and say, just quietly, to yourself, alone,

Thank you!

You see the mallet you made, cast your mind back to the day

you made it from scraps of wood with your own hands fifty years ago

and something floods into your very soul as tears of joy, of gratitude,

of humility bring you to raise your hands high.

And here it is, another day you left hunger at the door, another day you fed the kids good food,

and that from the work of your own hands.

It’s more than just another plane, another hammer, a saw,

a spokeshave, a rule and a wooden pencil or knife even.

It’s a way of living life as a maker woodworker and struggling against

all temptation when another says, “When are you going to get a real job?”

Being a lifestyle woodworker making furniture for life is to

follow a vocational calling that doesn’t tick all the boxes

in our modern world.

Guess what?

I did it!

Hence the old adage, “Buy once, cry once”. My miter saw and table saw have laid for themselves multiple times over and have helped me in the acquisition of new tools, whether hand or motor driven. I know that with each tool, comes new possibilities, challenges I can face, techniques I can learn. I hope to have a very full and broad collection of woodworking tools and be skilled in each one by the time I start to grow gray, and that I could make whatever I envision through the years of collecting both tools and experience with them.

I hope all who read this, especially Mr. Sellers, dont take this the wrong way. I admire the hard work and congratulate everyone who has managed to navigate life, doubt, fear, etc, etc to now look in the mirror and say, I did it. I hear so often, from long experienced and dedicated crafts people, about how they got started some 60 years ago and they toted their tool box up hill both ways to the job site and on and on and on. Fact is, the world you long experienced makers lived and worked in and through no longer exists. We can’t do what you did any more. Period. It was a very different time back then even if it was 1965. $37,000 a year to work as a dedicated cabinetmaker for a decent firm can’t cut it unless your spouse or significant other also works a decent job. That pay was half that 60 years ago and that pay went a lot further. It is extremely difficult to make a decent living as a woodworker these days and anyone who suggests that it isnt is sniffing something harder than super glue. Now, I understand you’re saying it still requires hard work and sacrifice and dedication and devotion and an adjustment regarding what you feel is important and what isnt. I get it. You want something bad enough, you do what it takes. But I see very few institutions that “train and teach” the crafts people of today for careers tomorrow that open their eyes to the day to day reality. Being successful crafts person today is a flat out grind and trying to sell it based on what life was like way back when does an injustice. I’ve worked at furniture making for over thirty years. Its hard work and it wont make you rich. But we go into this profession knowing this. We like to say it isnt about the money but money is what pays the bills, for the shop and for the home and for those kids who want to do things and go to school later on. I dont mean to be a downer on our profession, but there is a reality. Work wood for a living if you cant imagine doing anything else and you truly believe this is your life’s path. But understand, this career path is hard. Very hard and if you run your own business, you’d better be as skillful with your balance sheet as you are with your hand planes and spoke shaves and hammers. I’m thrilled Mr. Sellers that you have attained a level of success and self satisfaction that makes you smile in the mirror every day. We should all be so fortunate. But no one reading this is going to be making pieces for presidents and museums. You were and are highly skilled but you have to admit that there are plenty of times in that melancholy of your memory where you were just plain lucky too. Just sayin.

It was diligence, hard work and doing no unhealthy thing to my body and mind for the better part of my life mostly. Luck is not really in my vocabulary and “plain lucky” is far from it. If someone walked through my door today and said they wanted to be a furniture craftsman or woman I would likely tell them a lesser amount about what you said and leave the negativity out the door simply because as they progress they will have to face many battles but it won’t be listening to naysayers: I have had those each decade of my working life. If they have the desire and the drive and someone to believe in them, I believe that they will make it just fine, as I have. Oh, and I didn’t just live back in 1965 and stay there, I continued on through almost six decades on two continents to date. If I started over tomorrow, I would do exactly the same as I have done but with the added advantage that the internet has brought to us, still making it on a single income wage most likely, I believe. Self-belief is 95% of everything we makers do as long as we are realistic. Can everybody do that? Not everybody wants to so why should they?

Please do not let my comment start a political debate over what should and should not be done, but the discussion here between Paul and Drew must consider where a person lives. In the US, people fending for themselves have a huge price tag to pay for health insurance while in other countries, it is different. There are other costs that differ country to country and different levels of social network and community support. There are differences even state to state in the US that affect costs. It is a complicated issue and I won’t pretend to know the answer, but it affects things.

At the risk of going further towards starting a political debate, I will say that I believe that we in the US have been foolish in our sense of independence and privacy. In my opinion, have have gone so far with the notion of independence that we have cut the threads of the social fabric that previously connected us to each other and that supported each other. As a result, we become weaker and dependent upon the corporations that employ us to be our sole source of security against disease and feeding ourselves.

Superb points Ed.

Drew:

I respect your viewpoint and i believe most of what you say is based in truth. The problem I have with your comments is that you 1) make too many generalizations and absolute statements and 2) you fail to realize that very few career paths one can choose today offer any brighter prospects. Our world over the past two years has gone from a slow, “managed decline” to a rapid, in your face destruction of prosperity for the working masses of people. I guess my point is that youngsters today are going to be serfs, no matter what career entices them.

One more thing I will add is attitude and mindset do matter and when you ooze negativity and doom, success becomes harder to attain.

Since roughly a 3rd of the cost is raw materials, you could shave off a lot of money needed to be earned by owning a few acres of woodland that you managed by coppicing. Put in a wood burning fireplace at your house, and you also reduce winter heating costs because you will have firewood. If you’re the adventurous type, you could also plant some fruit trees in your woodland so you can get some free food. Don’t forget to look at the plants growing in the undergrowth, because some of the medicinal plants can be lucrative too.

I live in Florida, and have my bench in the garage facing out onto the residential street. Whenever I am working, I have the garage door open. It’s wonderful. Sunshine and a breeze off the ocean.

What has surprised me is the number of people who walk or drive by and stop to ask if I can build them this or that. They are willing to pay. They have seen me for months or years in the garage with handsaws, planes, and chisels, and I suspect they find it odd. Can I make a table like the one pictured on their phone? How about a garden bench? A new rocker for the broken one on great grandfather’s old rocking chair? Coat rack like the one they saw somewhere? A coffee table that doesn’t look like the ones from China?

I don’t need the income, but I always ask them why they don’t get something at Home Depot or Ikea. The answer is always the same. They just can’t get what they really want.

So, I detect a market out there. I’m not sure how one would reach it, and I’m not sure how big it is. But it’s there.

Everyone has luck, both good and bad. For most it balances out in the duration of a lifetime. The best aspiration is feeling that life has been worth it when you get to the end.

Drew,

Luck has nothing to do with it.

It is all just plain hard work, determination and most of all self belief.

I started out in 1989 as a Luthier after I finished my Boilermaking apprenticeship.

Everyone said I was crazy and that I would never make it, especially with the recession that was beginning at that time.

I refused to listen and I plugged away and during the years that followed I have travelled, worked with some very talented and famous Musicians, bought a house or two and rrtired at the grand old age of Fifty…

If a muppet like me can do it, there is absolutely no reason why anyone else can’t do it.

Why would retiring at 50 from something you chose and supposedly love doing be a positive thing? I wonder what that looks like?

You did it indeed,and hats off to you. Just goes to show what determination and strength can do no matter what obsticles and all the other stuff that gets in the way. Long may you continue to teach people like me. Many regards

Hi Paul,

Thanks for all the information you share here! I came across your website, watched a few videos, and was instantly hooked!

I’m not sure if this is the right place to ask a question, but I’m new to wood working and I just finished building your workbench and could use some advice. It was a great project, however I am now concerned that I did something wrong as I am noticing the top will vibrate side to side when tapped on at the end with a fist or even sometimes while planing using the vice even though the legs remain in place on the floor. It’s almost like a sway side to side, maybe not more than a 1/16” or 1/8” of deflection.

The top is a bit thicker than your recommended dimensions (~3 1/4” as opposed to 2 3/8”) and the legs ended up being a bit thinner (3” x 2 3/4” and opposed to 3 3/4” x 2 3/4”). I made the aprons a bit wider to accommodate the extra inch or so of bench top thickness and the bench is maybe 7/8” taller than your recommended dimension.

I’m worried that I just wasted a lot of time and material! Is what I’m observing normal? If not, is it easily repaired?

Any help would be greatly appreciated! Thanks again for all the information you share!

-Keith

If I understand you correctly, the bench moves from side to side when you stand facing it at the work position? If so, check where the racking occurs. Are the legs secured to the top well? Are the wedges loose?

I made my bench 2 metres long and 80 cm wide – a wee bit bigger than the plans. I don’t have any racking going on, and I haven’t added lag bolts through the aprons yet. The wedges and a few screws is all that holds the top to the legs. No problems so far. This really shows how well the design works. I can’t remember now, but I think my legs are about 3 5/8” square. I used 48x98mm material for the lamination, but some of the material was lost to jointing and planing/squaring.

You can clamp a board diagonally (at 45° -ish) from 2” off the bottom of a leg and to the apron and see what happens. The design should not need this, but it is a well known way to construct a work bench – I think it is called a planing brace.

You haven’t wasted anything, but you might have to do some things a bit differently. I highly doubt that you can “bend” the legs, so there must be something else at play here.

My first thought was “check your wedges and drive them in!”. When mine came loose, the bench moved a lot. 🙂

I made my version of it with no wedges, but never had any movement. Mine is just held by coach screws into the top and coach bolts into the aprons.

Keith, You can probably get more detailed help by joining the Master Classes. If I recall correctly, you would be able to participate in the discussion forums and ask questions there, including posting photos, even with the free membership that doesn’t have access to all of the videos. There might be info at Common Woodworking, too. Look at the top of the page for links from Paul’s header. I’m not affiliated with them in any way….just a former student.

I’ve taken my time to answer here on this Keith simply because it’s impossible to give a definitive answer or suggest what could be wrong. It’s the first time in what is likely to be thousands of benches having been made around the world that someone has mentioned what you do. I have worked and still do work from this very bench as between me and everyone else here we currently have a half a dozen such benches that are either fairly new or roughly 10 years plus old. I have also been using them in schools for 25 years. My thought was did the aprons get glued to the benchtops, something like that? It feels like a linkage problem somewhere, a gap of some kind.

Thank you for you response, Paul, Ed, and Vidar! My apologies for my post being off topic.

Paul, are you saying it would be problematic if the aprons were glued to the bench top? They were not in my case, but the wellboard is fit in VERY tight – I really had to hammer it through the groove. Perhaps this tightness is creating an undesirable linkage?

I checked the wedges and hammered them in – they seem secure. The legs are vertically level.

Maybe I have an unrealistic expectation that there should be absolutely zero movement in the bench?

The apron should be glued to the fore edge of the benchtop, yes. None of the dozens of benches I have ever made had the flex you speak of so something did go wrong. What wood did you use?

Hi Paul and Everyone,

I used regular old pine dimensional lumber from big box stores. I did glue the front apron the the bench top as was done in Paul’s video. I had adjusted the size of the wedges for the thicker bench top as well.

I removed the carriage bolts, levered the wedges in a bit more if I could (two of them moved maybe 1/16” further in.) Even without the bolts in place and just using the wedges to keep it all together the bench seems to vibrate similarly.

After reading a bit more about racking, this seems like vibration as opposed to a racking (unless vibration is a type of racking). The bench feels like one solid mass and it doesn’t feel like any part isn’t connected to another. It almost behaves as if the top is too heavy for the legs (again, I deviated from the plans as I have a thicker top and thinner legs since I used US 2x4s for the bench top, my inexperience with planing led to me taking off a bit more on the legs than I should have, and the bench is 1” taller.)

I measured the distance between the legs in the front and back of the bench – all are the same and they do not seem to be out of square.

What I observed is when I plane and say hit a knot, that’s really when the vibration kicks in. With a sharp plane going with the grain, everything feels great.

Maybe I’ll see if I can drive the wedges further, bore the carriage bolt holes a bit wider, and maybe take 1/2” off the leg.

The wedges should have been tightened before boring the holes for the carriage bolts.

The holes for the carriage bolts in the leg must be of a slightly greater diameter than the carriage bolt diameter; otherwise, if the leg has shrunk, the wedge will push the leg against the carriage bolt instead of pushing the leg against the dado side (making a pivot). In other words, the carriage bolt should not hinder the left-right movement of the leg.

Try making the hole in the leg a bit larger (or elongate it horizontally) and use a washer of sufficient diameter under the nut.

I hope this will cure the problem.

Problem solved above. apron not glued to bench surface, hence can rack.

As I said above, i omitted any wedges, but my bench has never moved, it is now over a decade old. So my legs are either held firm by yja carriage bolts or the groves on the back of the apron, which were very tight against the legs, when I assembled the bench.

Sounds like the wedges aren’t doing their job? I don’t think the changes in dimensions will matter too much, but did you make the corresponding change to the dimensions of the wedges?

Not the Paul!

Interesting thoughts. I don’t think you spark a political debate by making these comments. If one does even a simple search online for thoughts on whether a craftsperson can make a decent living in the US, its interesting to see how many comments there are about the necessity of knowing the business end of going professional. Make no mistake, I am in awe of Mr. Sellers well earned success. I have every book Paul has written! LOL I have learned a ton watching him work. He is an artist, not “just” a woodworking professional. I don’t know many pros who can/do make a good living using predominately hand tools. Many accomplished craftspeople have turned to making their living through youtube channels. Online instruction. The familiar brick and mortar shop isn’t a norm any more. I agree with you about how we have become weaker and dependent upon corporations. Here is the reality from which I speak: I have had a side business for years. I’m a criminal prosecutor and have been for nearly 40 years. I’d love to leave that stress and trade it for the stress of trying to make a woodworking business go. But. I have kidney disease. I survived colon cancer. My medical bills since 2014 total more than two million dollars. I am insulin dependent diabetic. I simply cannot survive without the tether I have to the county health insurance. Every day I resent it but I have to tell myself things could be much worse. There are others like me. you may know them. I’ve made a point of following the progress of exceptional woodworker Nancy Hiller and her fight with pancreatic cancer. I agree with Paul when he says if someone walks through the door and wants to work wood professionally, why would we discourage that? I derive the same satisfaction that he talks about from my shop and my tools when I stand back and look at my work and see that I “did it” with my own two hands. But I do believe we can’t deny or ignore that at least here in the US, its tough to make a business work. Especially fine woodworking. Most of us are simply not going to replicate Sam Maloof and get paid mid five figures for a rocking chair. And maybe that, in a way, is what Paul is trying to tell me. Sure, we want to be paid for our work. But most professional woodworkers don’t do it just for the money. I believe they do it because they simply can’t see themselves doing anything else. They may have tried the 9-5 career, but it leaves them empty. Using their hands is their calling. Their vocation. And the sheer satisfaction of creating with your hands is enough to overcome the lack of many other material things that they might otherwise earn. It comes down to having what you want vs wanting what you have.

You have hit the US nail on the head. The main argument from so-called American libertarians against a single-payer healthcare system similar to that in nearly every other first-world country is that it would impinge on our “freedoms.” I contend that is utter nonsense. The bulk of our national financial servitude can be tied directly to debt–most of it medical-related, either due to the ever-increasing cost of health insurance (borne by our employers as well as us as individuals) or due to the cost of out-of-pocket medical costs, pre-deductible or otherwise. Now image the actual FREEDOM we would experience if we as both employers and individuals were not constrained by that financial yoke around our necks. There is a very real reason no one is clamoring to reproduce our healthcare “model.”

My daughter lives in a very nice area in Long Island. The houses all look like mansions compared to where I live. I noticed was the type of vehicles in the driveways at night. They weren’t sports cars and limos. They were work trucks mostly. I saw that there were plumbers, electricians, and tradesmen of all types. People who are very good at their trade seem to earn much more than others. My father told me this years ago, and I didn’t listen.

i feel for you drew. medical costs in the us are 3 times more expensive than they are here in nz. most of this is down to the fact that insurance is so expensive to cover the costs of drs and prescriptions. in nz we buy our medications in bulk at a fraction of the cost of the us, who usually have made the drugs. that is down to the pharmaceutical companies paying the us legislators to ban a single entity buying for the entire country. hence each hospital. chemist shop etc having to pay extortionate prices. always follow the money. i was lucky here in nz. i was able to make a living making individual commission pieces for clients who wanted something the big box stores could not provide. i admit freely that i used machinery to do all the rough dimensioning as i was unable to ask a client to pay for those hours. but finished everything else by hand. 99% of my work came by word of mouth. breaking into the circles who have the money for this is not simple. but once in, a living is possible. also i work from my garage at home so no overheads for buildings, and my list of tools is small as i refuse to buy a tool that will sit on the shelf and gather dust to save myself 5 minutes in 10 years.

Pricing of US drugs domestically and internationally is a complex economic situation. It’s not due to anyone simply allowing or prohibiting something.

US developers spend a fortune bringing a drug to market. They can sell it in the US at whatever the market will bear, but they are constrained in most foreign countries by those countries’ government health care programs. Those programs dictate what they will pay. And they are perfectly willing to go without the drug if it won’t fit into the appropriated funding. (There are no national healthcare systems that do not use rationing of one type or another to curtail costs.)

So, the drug maker is confronted with a classical marginal costing problem. Since he is already making the drug, and development costs are all behind him, marginal costs of incremental production are X. If he can sell to a nation’s health system at X+Y, his profit is Y. Or, he cannot sell and lose the opportunity to make Y.

So, the US consumer subsidizes the foreign health systems.

But, then, let’s limit the price in the US! Show them foreigners we won’t take it! OK. Do that and new drug development stalls. The people who have drugs for their conditions are happy. The people whose conditions do not yet have a drug can die.

Various US administrations have toyed with fixes. Trump wanted to tie US prices to foreign prices, forcing the foreign health systems to pay more, and pushing the manufacturers to hold out for more. It’s a classic economic problem, not at all easily laid at the door of corrupt legislators. But, I agree. Follow the money. But always follow it to where it leads.

And our aspiring woodworker? If his spouse has employer provided insurance, he’s OK. If he’s young, he accepts the risk. If not, he does indeed have a problem. Before 2010, the young guy could buy a cheap plan based on his age. No more.

I am barely approaching a few years into the profession of “woodworking”. I started off as an installer, particularly residential cabinetry. I soon found that I caught “Krenov Syndrome”,finding a love for the material of wood, the tools involved, and the idea that I could make things that could suit a variety of purposes that are just as endless as the intricacies of the craft itself.

There have been some comments made about the practicality of making a living as a woodworker that I have an ambivalent view on.

Being as young as I am in this craft, I am still in the honeymoon phase with it, and hope to be for many more years. I am of the conviction that if I am to be successful as a woodworker, I should use evey tool at my disposal, not only as a woodworker, but as one who seeks to eventually start a business. This means learning about the intricacies of balance sheets, understanding how to market myself online and locally, making wise use of my resources. But I also have to develop myself in my chosen craft, understanding the nature of my tools. The art of business can actually blend quite beautifully with the craft of woodworking, if you have a clear vision that you relentlessly pursue. It will be a journey, but I see myself being well versed and skilled in a variety of technical areas of woodworking, enabling me to eventually create truly unique, well designed pieces, which will increase their value, which increases capital, which will increase the potential for the acquisition of machines that have the capability to produce in mass quantities. With the advent of new technologies, social media, and other new information available for free from people like Mr.Sellers, there’s no reason why one can’t find a way, with hard work and grit, in making a profitable woodworking business. These are my thoughts. Take them for what they are.

Very interesting Joel, I wish you the best of luck!

I’m interested in your goal to acquire machines that produce in mass quantities and how it relates to creating truly unique pieces that will increase in value? Seems a little paradoxical. For example, my in-laws bought some well-made, nice looking furniture from Oak furnitureland (in the UK). They bought it because it was inexpensive, and a glance at any second hand site shows that it doesn’t retain value (but does sell well). They fit comfortably into the mass production space, producing good furniture at low cost.

Or is it similar to the band that produces an edgy, raw record with meaningful lyrics that makes its way on the small venue circuit before releasing a pop tune that sees them sell out stadiums within years? I’m not being critical, it’s out of pure curiosity that I ask your goals, as they seem to be competing slightly! Perhaps you have an idea as to how you can do both, which would be great. I’m intrigued to see the direction of the industry with the advent of CNC (at a medium size workshop level), and whether that brings more players to the game, or whether it’ll be the case of the biggest company with the biggest machine(s) wins. I can see a space for the maker that can perhaps hybridise the system of machine production, with the effort of wood sourcing, book-matching, hand cut joinery etc to create limited runs of furniture. I’m sure there’s a sweet spot there somewhere. I really hope you find that spot!

It’s funny that people are adopting terms like hybrid and minimalist when for centuries to date most woodworkers like myself have indeed run hand tools alongside their machines very successfully just being, well, ordinary people making. Personally, I think it was a calculated term as was calling machines power tools by woodworking machine manufacturers and magazines. Somehow they had to bridge the gap between traditional terms as in hand tools to somehow legitimise the downsizing of machines for the domestic home market, which in the mid 1990s was an untapped and emerging sales field yet to be harvested. Hybrid of course, has a built-in obsolescence in creating seeds that guaranteed people couldn’t then grow their own any more. The hybrid had on the one hand a good purpose that produced a bigger and better yield, things like that, but then it led to a control that made growers return to the engineer producing the seeds. The idea is to now produce a seed that can be sold and controlled. No one can rely on the seeds for long-term reproductive reasons and seasons. As it is with disposables of anything, knife blades, handsaws, etc, the purchaser must constantly return for the rest of their lives, thus ensuring a return for purchase via built-in obsolescence. Minimalist too is a little silly. Most of us rely on a small amount of woodworking hand tools and mostly those we pull near too for our minute-by-minute use. Thankfully, skilled and creative makers rely on their skilled workmanship to develop their reputation over a number of years. It’s a buildup of internal support. Keeping simple books and marketing is easier today than ever. Be honest, open and transparent and simply be diligent in what you do. It hasn’t changed in centuries you just do what you need to do to be honest and you don’t need to rely on gimmicky output and razmataz.

I do agree with your sentiments towards the marketing aspect manufacturers have employed with normalizing home machines. Not everyone owns a CNC, nor necessarily wants to. For a beginner like me who operates on a tight budget, using reclaimed materials, and slowly building a collection of both hand tools and machines, the purposes come down to matters of practically and ambition. I want to do this as a living and as a way of life. By your judgement, the term “hybrid” must be a more recent phenomenon, but it always implied to me the use of machines for hogging out the big work (like maybe deep, wide mortises with a mortising machine) then fine-tuning the cuts with chisels. I’m very much an amateur in my own estimation, but as one who discovered a craft he loves and wants to excel at, I find that machines are grand things for helping one to acquire more tools. Most of my money goes to living expenses. But as I acquired my first electric miter and table saw, I was soon collecting planes with the profits, since I had people like you to inspire me to take my skills to the next level. So with that, the power tools in my little shop are a means to an end. The work horses that help me to obtain the hand tools I desire to build other skills and pay homage to the craftsman of the past. But even with cast iron planes, they were still a recent phenomenon, following the marketed transitional plane that helped craftsman to adopt the idea of a metal plane. I wish to do big things with this craft, but I’ll always acknowledge those who have come before me and paved the way, as well as provided and recorded the knowledge, to help me obtain my goals.

Hey Rico!,

To clarify my sentiments, my goals and thoughts with incorporating machines have multi-pronged inferences in regards to what product could be made, or what market would be served. There are multiple uses for a variety of machines. You can use them to make IKEA quality affairs that won’t last the passing of time, which to me doesn’t seem attractive to a passionate woodworker. You also have people like Wendell Castle and John Makepeace, whom have an eye for design and find ways in which the programmable machine can still do wonderful things that result in unique, valuable pieces (depending on how you value it). William Morris had a disdain for the industrialization of the craft, while other constituents of the Arts & Crafts movement, like Gustav Stockley, preached his sermons but were not afraid to capitalize and profit upon repeatable yet eye catching design (as I think they should). Even with modern commercial markets, heavily reliant on MDF and particle board cores, veneered with plastics (or in some cases, wooden veneers), though not the epitomy of craftsmanship with the machined modular, frameless designs, are still profitable ventures. It depends heavily upon your goals. For me personally, a simple CNC at home to produce templates and cut repeatable products have possibilities for increasing profit margin, given that I have a ready clientele or market willing to buy my products. This can lead to an increase in retained earnings that get help you to acquire space and more complex machines (these are long term goals of course). With a hybrid method of woodworking, one could very possibly run programs to machine out sets of arts and crafts furniture, and have them touched up with capable hands further down the line in the production process. If a company is big enough, this type of production responsibility can be handed off to a trustworthy member of the company, while the leader opens another department that requires more time for truly custom made pieces, depending on the client. Perhaps a custom desk or table. Maybe trim will need to be shaped to match with the design elements of the piece, so a shaping table with customized blades cuts trim to match. Or maybe it’s done with moulding planes…It would rely heavily on the client and what story they want their woodwork to tell. The possibilities are endless. “The craft so long to learn, and the lyfe, so short”, yet this is part of the inherent beauty of woodworking. You will never master every aspect and you will always keep learning or improving, whether in the craft or in business. It would be a lot to manage, and the cultural ethic of the company would have to be demanding, yet rewarding. It’s possible. My goal is simply one step at a time, to keep learning the craft while building my knowledge in other areas as well. That’s where my mind is on the matter at the moment.

Once something is mass produced it is no longer unique!

I always read Paul’s blog with utter amazement at the path he he gone down over a great many years. I’d like to close my eyes and pretend I am him in 1965 just getting started. But then the vision turns to reality. While there are opportunities in a big city like mine for commercial work, work in the private sector is hit or miss. I’m sure a few are following there dream once established (Key word), however many are not. One must have talent, one must have both administrative and sales experience also. And finally one must have a sufficient amount of money in the bank to keep them financially stable. At 61 my woodworking is a hobby. My exterior home business pays the bills and has allowed me to outfit and fully stocked shop of all tools small and large. There are few folks left like Paul in my world today. I’m just thankful he allows me to dream through his many years of woodworking.

Got to admit this one left me a little weepy in a good way. I also have perused my set of tools collected over time but certainly not from age 15. What a lovely legacy.

Another plug for the Poor Man’s Tools! Now you don’t have to spend a week’s wages if you are handy! Build your own bespoke hand tools!

Can someone make a living using PMTs? I believe they can.

I knew a fella who was a handyman. He worked with hand tools and a cordless drill. He was able to make a lot of (tax free hehe) money because a GOOD handy man is hard to find. Many of his customers were single mothers and needed help with everything from gutters to wooden baby gates. He built fences of wood and wire, built bedframes by hand, decking, on and on it went. He could have sold bespoke furniture to them at a modest, reasonable price. Maybe a Sellers rocking chair? Maybe a Sellers baby crib?

Is a woodworker only a furnituremaker? Cabinetry maker? Or are they a jack of all trades? Paul did some blacksmithing in a few videos as I recall…none of us are one trick ponies…we can generalize and make a great living doing so.

30-35 years ago my wife and I went to a craft village. An artist in residence was making stained glass pieces. He was grinding out “mass produced” suncatchers that could be sold from the showcase at a “reasonable” price. There were not a lot of folks there, so we were able to talk to him for a while and asked about a much larger piece in progress on a table toward the back of the shop. It was restoration of a large stained glass window. His joy and satisfaction talking about it was evident, although it was followed by the comment they had to make the mass produced items cheap, easy and quick to pay the bills so they were able to stay in business to be available to work on the once a year or so projects like the restoration or a request to make a custom order for a new piece. That was 30 years ago and it feels like there are even fewer of those able to afford the prices needed to recoup the time, materials and experience to make a Sellers rocker or any other maker’s unique item; even with eBay, Etsy and other electronic means to reach the buyers. They make it easier to advertise, yet you are buried in amongst the hundreds of others trying to do the same. I’m glad Paul has been able to support his family over all these years, but need to ask, wasn’t the income from sale of made items supplemented by salary from teaching and book sales and video income? Not all makers can do those things or become so well known to demand high enough prices for their pieces to make ends meet. I hope to get out in my shop much more once I retire from my IT position of 44 years, but have no expectation to be able to match my salary, even if I were able to match Paul’s craftsmanship. It will, for me, have to be due to a love of wood and the joy of creating, not that it will be able to support me and mine. I would not discourage anyone that has a fire to create from following that path, and do wish them luck to find that particular niche where they will be able to support themselves using their craft.

Whether one goes into woodworking early in life to earn a living or whether one goes into woodworking late in life to continue living seem to me to be one in the same but only at different times in ones life. I chose the latter and my workshop is filled with old hand tools that I either inherited from my father, purchased from junk yards, or were donated to me by friends and definitely in need of some kind of restoration, tuning and using! Paul, you have given me the confidence to use these tools and the skills/knowledge as to put them into a useful condition. That itself was as important as using them. My children and grand children have reaped the rewards of this “hobby” that has made my last 15 years feel useful and a joy to my heart when the grandchildren come to me and say “Grandpa – let’s make something!” I still use and remember when I bought my first block plane and handsaw – a Stanley 9 1/2 and Disston D7 and still use them today although I know now how to respect them, sharpen, clean and oil them and have given these skills to the grandkids. I am also glad that I took High School shop where I learned just enough to know that some day I would use these skills. SO, I didn’t earn a living with these tools and skills, but I have earned a longer life by using hand tools and the few power tools that help doing this simple woodworking.

For my 18th birthday in 1973 I asked my parents for a set of tools – a Record plane, a mallet and a couple of cabinet makers screwdrivers. I still have and use them along with many others that I have acquired along the way. For a long time I used them for DIY work as my career was laboratory-based. However, at the age of 50 I resigned my academic position and set up a business building and restoring traditional pipe organs. Among my tools are two sets of Record moulding planes (ca 1940) as I hate using machine like spindle moulders. I make all my mouldings by hand. Of course, I say to people that if I was a young man with a family and a mortgage, I would do a lot of worrying as my second career has never brought in much money. The real compensation is restoring a mute musical instrument back to life using the same, or as near as I can achieve to the same, techniques employed by the late 18C or 19C craftsmen who did the original work.