It’s All Gone

I looked inside the wooden box where his tools were always placed in an interlocking pattern that allowed each tool to fit into or beside another but only one way. I knew to look only for a short second, barely a glance, any longer and I’d get a cuff around the head and a harsh word accusing me of ‘casing the joint ready to steal something’ when his back was turned. Of course, I wouldn’t, but such was the culture of the day. Ten benches with a four-foot spacing between and set in a rectangle would be the rarity today as it was then. Wood and the working of it from beam to chairs and tables by hand with an odd trip to a machine in between are all but gone in most shops these days. Here, I am talking about toolboxes and chests laden with ebony and rosewood infil planes, wooden squares, sliding bevels and much more. Wooden plough planes, filletsters were fading out as tools of use, Jack planes in beech and then some vintage tools we would most likely have no knowledge of any more lined the insides of the boxes and perched on the benches nearby. I was in those transitional years when these chests and toolboxes would go with the man when he left for final retirement and they would never be replaced; no one would bring such things to their workplace to work from them or use them again in any ensuing generations. I saw it then and it did indeed come to pass.

I watched as the first powered router guided by special fence guides routed out recesses for hinges, and electric drills were replaced by battery-driven versions, in the same way I saw the first pocket calculator add subtract and multiply in a salesman’s hand for the first time. It cost almost a week’s wage. We look to the past with reverence as a sort of mysterious period when men made to levels of excellence we see in the mansions of the rich and powerful past. Such work is no longer made and those tools exist mostly in the realms of collectors, museums and associations. Tools and trades history societies do little if anything to keep craft alive except in the most artificial of ways by somehow perpetuating historical obsolescence; instead of encouraging the true art and craft of craftworking, most colleges give a nod to the past by using teachers who have little if any mastery of handwork and craft by teaching a one-day class on how it ‘used’ to be done ‘in the past’.

In my world of making nothing really changed much. I’d made up my mind and made hand tools work through the half-century of making and selling everything I ever made. A made-up mind is the key to everything. Whereas I was raised with machines, it was also in parallel to the daily hour-by-hour use of hand tools too. In my workplace, what one man didn’t know another man did. There was a healthy exchange of ideas, thoughts and skills that passed between woodworkers within the region as they came to trust one another by working together. I am not too sure that that really exists today simply because most never develop that sense of coequality and trust and then too, with the demise of truly skilled handwork and the need of it, there is no need for skilled work anyway. The natural progression is therefore that skills die a little bit year on year. In my early years, when one left a company and transferred to another the cross-pollination was remarkable, I thought. Conditions, work type, coworkers and geographic locations all influenced and facilitated this exchange of not just labour but thoughts, ideas, helps and supports alongside the reality that it was healthy for the craft simply because with it came the exchange of knowledge to perpetuate diverse skills within the trade. Unfortunately, in my view alone, it seems, it wasn’t enough. Skills were tragically lost and mostly because of lack of self-belief. Until they see it done, carpenters don’t believe that I can chop a recess for a hinge accurately and at speed in a minute or two with just a chisel, a gauge and a mallet. The difference for me is that I can dip the back edge of the hinge in a perfect plain and ‘Scotch’ the hinge in the traditional way that no powered router can.

As the skills diminished and global mass making created its own self-diminishment of skilled workmanship, my craft was to go. It went to the point that it is really all but gone as a way of industry. It really hadn’t needed to, just that industry believed it needed to and I get that. Business people buy and sell companies as an investment and want a high-profit yield to fill their bank accounts. They are just investors for the making of money and little else. `They can’t really buy people with a moral ethic for art, hence the demoralisation of style and skill where every interior looks identical, just about. I am amazed at the low cost of wooden furniture produced for use in commerce and domestic places. I pay £300 for enough oak for a dining table yet industry makes, supplies and distributes an oak table from China for just a couple of hundred pounds more and it’s really quite well made too. Indeed, it may not be heirloom quality but it will last a growing family until the kids leave home. How to compete with that?

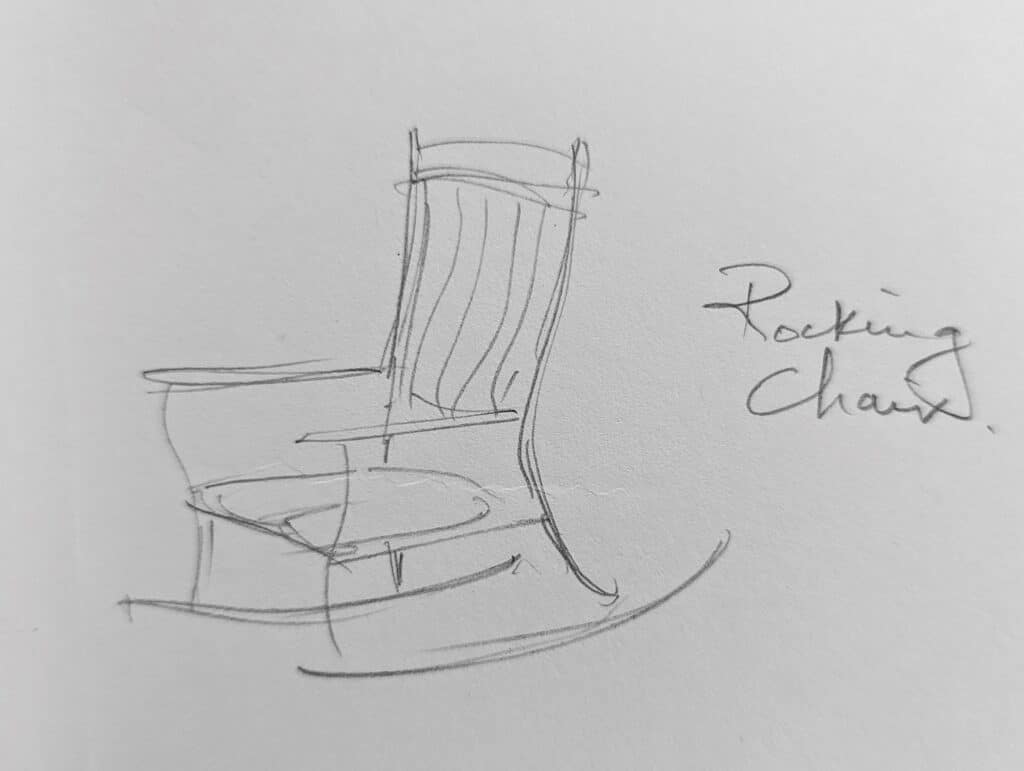

Well, the truth is, I did and I still could even at or especially at my age. You see there is still a customer base that looks for other ingredients when they are looking for a piece to buy. Can they find something to make do or can they buy something customised to fit and of a quality and style matching their expectations. Someone asked me how I can justify the price of $6,500 for a single rocking chair when they mostly sell for a few hundred at most. I think that most woodworkers sell what they make based on some kind of hourly rate. I recall one of my own customers balking at a price for a piece and trying to beat me down on price. I stopped him at the hourly rate thing. “If three independent carpenters come to your house and they are given an identical set of plans to build you whatever deck is on the drawing or even the specs for a whole house, you might expect the prices of all three to be closely comparable,” I said. When you come to me and ask me to design a piece of furniture like a rocking chair, something like that, you are not just paying an hourly rate, you are paying for my design, my design ability plus my ability and skill to make it. History has changed from the days when a man in the 1700s, 1800s tipped his cap or tugged on his forelock and said, Thank ‘e’ kindly ma’am!”

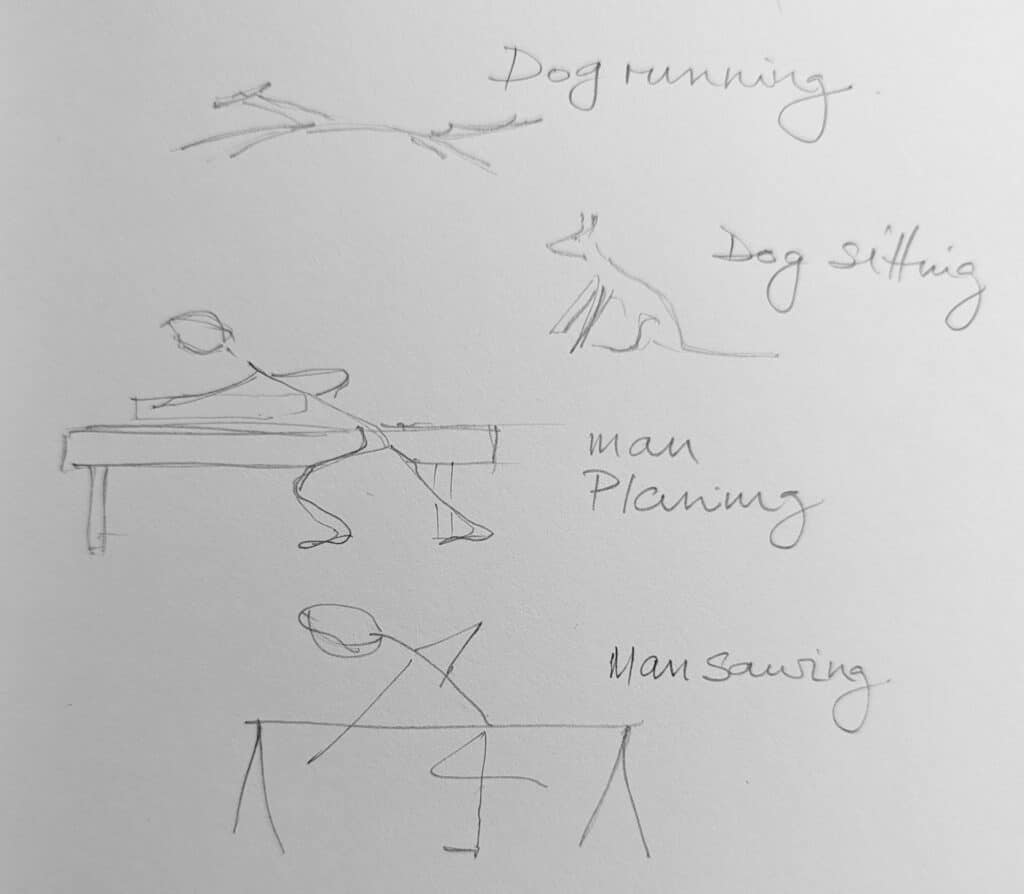

My ability to sketch out a drawing in front of customers and then make the piece according to the drawing is the scarcity and such skills should be mastered for the immediacy they give a craftsman for the customer. I chose this path with drawing when I was in my mid-teens. It paid off. It wasn’t so much that I was good at sketching but that I saw how people could not visualise things and so how could communication of an idea become the bridge we both needed without a drawing, and even the most basic sketch can communicate that you and they are on the same page. Of course, we automatically believe that we must be good at sketching and drawing before we do such a thing but the brain fills in the gaps, in the same way, cutting off the top half of a line in a sentence does not mean we cannot still quite adequately read the line. I found that with the most basic sketch, customers felt more confident that they would indeed get what they expected. Combine that with a portfolio of finished pieces and people felt it was less of a risk giving the go-ahead. These were the days when no one owned a cell phone or much of a camera and of course, social media wasn’t a possibility at that time.

I think that it is true that many if not most people don’t believe that they are able to be or capable of being creative and perhaps this can be attributed to the reality that many teachers never leave education to become especially skilled enough in particular areas of creativity to go beyond a textbook and manual and therefore equally incapable of talent-spotting creative people when they see them. In my sphere of making as a maker, photography, technical drawing and then sketch drawing too, I automatically project myself into the doing of most things. But, that said, I know my limitations when it comes to car mechanics, some plumbing work and electrics. otherwise, my creativity has translated into my using digital energies to be creative there to some level too. I have worked through elements of PageMaker, photoshop, social media in tandem to art too. necessity is indeed the mother of invention so inventing has become important to my life. All in all, I find that mastering one area of creativity often equips us mentally and physically, emotionally. Rarely if ever will this be reversed in the sense of people taking software engineering into the manual working realms though, of course, I have seen significant changes there in recent decades as all the more people seek other ways to express themselves creatively. This shift in recent years is coupled with people seeing the internet as a way of extending their ability to both make and even earn. Additionally, dumbing down making to a machine operation where shooting staples and nails, pocket-hole screws and so on give you the wham-bam effect for mesmerising an audience looking more to be entertained than skilled.

Becoming any kind of a creative takes the acknowledgment that gaining any kind of mastery takes dedication and practice. It’s an ongoing commitment not to cut corners but to learn how to become as highly efficient as possible and then economical with various elements ranging from time to money to materials and more. This was drummed into me as an apprentice when I thought time didn’t matter so much or that a miscut resulting in the need of a replacement piece could just be taken from the wood stacks. Nuh uh! No, no, no! So much to learn!

For what it’s worth… I received a “Casio” calculator on Christmas, in the mid 70s, when such things were new. I was then and still am, pretty good at mental arithmetic, but if I need a calculator, even though there is one on my phone, I still use the Casio.

I suspect it’s older than a few, (very few!), of the tools used by folk on here!

Regards,

Matt

Haha! I’m still using my slide rule, although it’s getting a bit “approximate” with wear these days!

Went from log tables to calculators. never used a slide rule.

I recall doing logs of logs by hand, nightmare, much easier with a slide rule. Still have mine.

When my mom sold the family home a few years ago and moved in with me and my wife, I cleared out the old home to get it ready to put on the market. Up in the attic I came across a log, thin black leather case that I recognized immediately. I opened it up and there was my old, trusty, well-used Pickett slide rule. Had to show my wife how it worked as she had never seen one before. Hardly believed that I still remembered how to use it, but it came back very naturally as it had been pretty much attached to me for many years. It brought back many, many memories of Pre-electronics days.

I recently dug out my K&E slide rule that I was gifted when I started engineering school. Never really learned to use it as I moved on to other things, but I am gifting it to my grandson (soon to graduate from engineering school) as a curiosity for his office. I’m including a copy of the book than came with it back then in 1966.

I remember using a slide rule in the university math and physics classes. I always had trouble deciding where to put the decimal. Your comment brings back quite fond memories of the past.

Oh yes, I had the same “decimal dilemma” with my slide rule way back in my college math and science days in the early 1960’s. Glad to know I was not alone.

Even in the university business and economics curriculum, I used a slide rule, keeping a small one clipped to my shirt pocket got me through on most things. We had no calculators in the early ’60s, except those grunting electro-mechanical things in the Statitistics Lab made by Friden and Monroe. Yes, I still have a couple of slide rules and I use them when they are closer to hand than my smart phone.

I was taught to have an idea of the answer before you start so that when the slip stick is finished you know if you have gone wrong.

Time and technology are constantly changing things. As we all reminisce the times before pocket calculators their were plenty of people from times past who could have reminisced the use of the lead pencil for calculating and before that perhaps charcoal on a board.

Of course man always falls pre to his own advances. Always trying to make things easier and quicker he doesn’t often comprehend that what he’s doing is taking his brain out of the equation. Using an electric calculator or slide rule instead of your head although easier in it self chews at the roots of creativity.

I still have and use my slide rule from when I was in college in very early 1960’s. Most people have never seen one !

David

OK guys. In the Navy, I was a Fire Control Tech. One of my tasks was to compute the initial velocity . Lots of “goes into’s” went into that final number. This number was dialed into the Mark1Able Gunnery Computer. One of the tools we used was a Nomogram.

It was a sheet of paper that had three vertical scales on it. I would line up a ruler on two of the scales (known values) and read the result on the third scale. This was a dedicated slide rule. It would only compute one result. If any of you have ever used a Nomogram I’d like to hear about it.

I am similar to you. I teach college chemistry one night a week for fun. I teach the teaching assistants who then go and run problem sets with the larger set of students. The teaching assistants are typically the ones who did well in the class. In chemistry there are a lot of exponents, square roots, and squares in the mathematical operations they must do. At the beginning of the year, I tell them that the should be able to rapidly get an approximate answer manually so that way when they use their calculator they can double check to make sure they didn’t punch something in wrong on the calculator. I’ve been doing this for a decade now and every year, the look is the same. At first they think I am crazy. I show them how. By the middle of the year they can easily do it. They were always capable, they just didn’t know how or believe it could be done.

My kids are now in their early twenties and grew up with calculators at an early age.

With a maths problem I would always tell them when they immediately reached for a calculator to solve a problem that the calculator is only the last step. All the other parts of the equation have to be moved around first before you need to touch any buttons.

I was taking Engineering classes in college (1977), but we were required to take a one credit course on calculators before being able to use one in class. The required calculator cost about $150, was twice the size of current cell phones and did only +,-,*, and divide.

I still have my Casio FX39 in its original box. 4 functions and a count button! Its older than the model on display in the London Science Museum.

Thanks for this Paul. Quite a few years ago, my professional job went very quiet for about a year. So I cleaned up my hand tools and went back to my old trade as a carpenter. When I went on site, there was a lot of criticism because I only had hand tools. they were all using power tools. It cost me quite a lot to update my kit to keep them quiet and keep up to them. Now as I am retired, I have gone back to hand tools and my power tools just gather dust. This is mainly thanks to you and your videos.

This is an exceptional post Paul. Thank you. I think your statement of “A made-up mind is the key to everything” is spot on. We are all going to live life. You either choose the life you want to live or you live some sort of life chosen by society. Personally, I’d rather choose my own life. I am absolutely convinced one can make a living as you have stated. One just needs to be a bit clever on how to make it happen.

I took architectural drafting when I was in high school and it turned out I had a knack for it, so much so that I had completed the 9 week course in 3 weeks. I did another project and for the last 3 weeks was asked by the teacher to help other students that were struggling. I can see the project I want to make in my mind and at that point I can draw it and cut it out. Apparently a lot of folks are unable to do this. I was unable to pursue this as my father passed away and left my mom and siblings without cash so I went to work but I have always kept that and use it all the time. At the time I thought everyone could do that. Apparently not so much.

Paul, you have a very special talent that few have.

I am an architect that went back to school in architecture at age 32 and graduated near age 36 and luckily began a practice at 38, now 40 years ago. You have no idea how many of my classmates could not do as you do. Sadly, there are a lot of two-dimensional architects (and more engineers) is why the profession has such ugly duckling buildings. You’ve heard the expression “”A” students, work for “B” students and “C” students get all the work”” is sadly very true. I hope in some way you are using that very rare ability.

Oddly I have found it to come in quite handy in my woodwork shop. I am able to just look at a picture or see a project in my mind and can do a full drawing. I am no artist but I am killer with a straight edge. I was saddened that almost all the classmates struggled with what was simple to me. If my father had lived I would have attended college but I had to go into the work force. My very first job was at the Royal Canadian Mint in Ottawa. If you run across any Canadian coinage dated1971 or 72, I made it, either the pressing, assaying, etc. They moved us around and I ran an open crucible melting pot among many other jobs. I thought that I was just a normal teen at the time of my doing the drafting but what I learned stayed with me and I use it a lot. Oddly so did my use of fractions now that I had a use for it.

Paul , I don’t understand the following sentence in the ‘It’s All Gone’ post .

‘I can dip the back edge of the hinge in a perfect plain and ‘Scotch’ the hinge in the traditional way’ . Could you please explain what this sentence means ?

Sure. A machine router will not generally create anything but a recess parallel to the surface the machine registers to. We often if not always recess the hinge out of parallel for a couple of reasons. Scotching a hinge allows the hinge to be recessed at an angle rather than level and this allows additional options for those who need the option. These are tricks of the trade long gone and lost. It works where a hinge cannot be recessed fully into both elements, ie, door and frame. Recessing the back edge of the hinge into a sloped recess from zero to the thickness of a hinge flap means it registers and has the benefit of the recess for support. Scotching a hinge means that both are marginally recessed in opposite direction.

Dear Paul, this is video material! I would love to see a video from you where you discuss this. I don’t see why it would be advantageous to not have a parallell recess no matter how I think about it. I would love to learn about this, because I am certain my lack of understanding will be replaced with an eureka moment and “of course! So simple!”.

There has been quite a lot of moments like that. In no small parts thanks to you. 🙂

I hope you could elaborate over the topic, if you have time in your schedule.

It is shown in a “Lost Art Press” blog post:

“How to Hinge a Door, by Robert Wearing” dated September 7, 2021.

Although, I would also like more explanation.

Totally agree! I sort of understand this, but seeing it done would be very helpful!

Hi, I recently picked up an 1890’s tool chest needing some serious repair work. The hinge recesses on the lid were angled as Paul described. The angle allows the use of full length screws, but because the recess is angled the screws do not poke through the top!

If the recess was parallel you would need shorter screws and the holding ability would be greatly reduced. Hope this helps!

Around the turn of this century I was a friend of Ron Goldman, who published Woodworker West, a bi-monthly magazine of woodworking and furniture making.

He invited me to meet Sam Maloof at a showing of Sam’s woodworking in Brentwood, CA.

I was able to talk to Sam a little, and I asked Sam how he made such intricate and light appearing joints in his rocking chairs.

I’ve never forgotten my surprise when he said drywall screws and wood plugs, without any hesitation.

Paul, do you think the very active of being creative requires practice? I don’t mean practicing joinery or finishing or other physical aspects of making nor the technical skills of drawing. I mean the act of generating an idea, of creating and conceptualizing something.

I think back to the days when I couldn’t really pull a sentence together even in my mid-20s. It was really about ten years later that I began to write sentences that actually made sense to others. That was out of necessity really. It was a discovery for me that writing was quite simply another art form like woodworking and drawing. I basically taught myself but I had a friend who was a copywriter who volunteered some basic input. Drawing classes in an evening art college course were for me a waste of space taught by a graduate who was actually learning from me so I quit that class and progressed my own unique style. Again, as with the writing, I needed drawing so I just kept going. Technical drawing came naturally to me and with two or three basic technical drawing books I soon picked it up. By these different elements that any crafting artisan working with furniture making should have, I presented work that people could comprehend easily. My customers got an ‘artist’s rendering’ by way of perspective sketches alongside technical drawings. I found that with drawings I always got the jobs I estimated for and never lost even one. I would say that for me it came naturally by way of the fact that it was interesting and thereby stimulating.

Ed, this is really the core idea behind LEGO bricks. I have very fond memories of all the creations I made when I was a kid almost four decades ago. I was lucky enough to have quite a lot of Lego bricks, although perhaps by today’s standards I had few. As I grew older, my parents gave me Technic Lego. I remember when I made a crude 3-speed transmission based on an image just barely hinting about the idea.

I have the ability to “see” solutions to problems and to imagine how something will look. For example, I am in the process of splitting bed rock (with feathers and wedges) to make a walkway from one level of our garden down to another. On each side I’ll erect a concrete wall from formwork concrete blocks, that follows the terrain down a slope. A lot like building with Lego, really.

Somehow, I can sort of envision how that wall is going to look when it’s finished. I “see” it in place when I’m planning where to remove bed rock and where I need to pour some concrete to form a foundation.

I think that this “gift” of being able to envision things comes from practice. From building with Lego blocks. You start out building basic stuff, and one day you discover a new way to put Lego bricks together. Perhaps you get a new set with a different kind of brick, and all of a sudden those things you wanted to do but couldn’t, becomes easy to do.

Of course I recognize having a good imagination helps. But isn’t our imagination just the ability to put together Lego blocks from different sets – different experiences and ideas? Perhaps all one needs to do is to practice imagining things.

To some it comes naturally, others need more practice.

Funny though – I can draw a decent sketch of an object. A chest of drawers, a car, a bolt – I could even sketch out my idea for our garden and how the wall would look, complete with the terrain profiles and all.

But I cannot for the life of me draw a face or a hand – not if I want to stay away from my inner Picasso…

Perhaps if the Lego blocks of my childhood was more organic in form, not generally just square?

Vidar, I think the ability to draw more organic forms is in you as well as you have “conquered” the ability to draw square-ish objects. The eye-hand coordination is important and then seeing something and replicating it comes with practice. A chest of drawers are stationary and you can take your time to draw it and after some practice from your “minds eye”, a person is less stationary and you have to be quick so to “copy” a picture is easier initially.

I had a friend in high school who was great at sketching and drawing both imaginary people and portraits so I said to him that I was impressed with his ability and that I would have liked to have his talent and how good he was at drawing eyes and hands.

His response was that “the first 1000 eyes wasn’t so good but after that they became better”. What he really was saying was that “if you practice you’ll learn too”. Regretfully I wasn’t keen enough to be able to draw as well as him so I gave up after the first hundred or so… 🙂

I’m not saying that some people aren’t more gifted than others or that everyone can be a Picasso (who was very good at “natural” painting before creating his own style) but with enough practice most people are able to draw quite well. Question is if we are willing to out in the work to get there.

It’s a bit like cutting a dovetail. The first might not be pretty but after a few (dozens really) they start looking acceptable. The old adage, “practice makes perfect”, really is true and then we have to be less critical to ourselves and keep trying to make it “good enough” – in all aspects of life.

Cheers!

Thanks for the encouragement, Jim! And you are probably correct – everything can be learned, but I think I am in the same boat as you – the ability to draw is not one i covet enough to invest the necessary time to “master”.

But I will say this: my “organic” drawing skills could certainly give Picasso a run for his money. But not because I am _trying_ to do that…. 😀

‘The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.’

Are the illustrations in Essential Woodworking Hand Tools your own? If so, you greatly underplayed your abilities at sketching.

They are all mine, Stephen, and thank you for the compliment.

Paul, could you please do a blog on your blue shop stool? You’ve mentioned it a couple times, I’d like to hear “the rest of the story” and make one of my own. Can sit on when I’m figuring at the bench and perch on the front of at times as well.

Thanks Paul. Almost Passiontide, so an early Happy Easter to you and family…

The great English innovator Henry Maudslay (1771-1831), who started off as an apprentice to a lock maker, said a similar thing: “First get a clear notion of what you desire to accomplish and then in all probability you will succeed in doing it.”

I like to think it’s not all gone. I woodwork in my garage shop and use the methods and techniques taught by you Paul. I’m finishing a stool soon and planning to make a lectern-style desk as well. I want to make chairs too. The chairs in my dining room loosen a lot (poor joinery). They are joined together with screws, nuts, and washers which is some cases work but not for a chair as far as I’m concerned. Why weren’t they made using mortise and tenon joinery? This is what started my quest in woodworking around 2011. I wanted well made, custom furniture that fit my home. I could not buy what I wanted in local stores. I bought some power tools to make what I wanted but didn’t like them, too noisy and I didn’t feel safe using them. So, I talked about it with my father and father-in-law. At that time, I was very green about hand tools. Of course, I knew a little about hand planes but I had no idea of how to chop a mortise (“Bevel in the direction you are chopping.”) I wanted to know how things were made before machines and I learned enough from my father and father-in-law (conversations only) that motivated me to learn for myself. They told me about a long standing American TV show that highlighted a woodworker who only used hand tools. I saw one episode and was fascinated. I decided that I was going to make furniture using hand tools I wanted. I struggled for awhile because I didn’t know how to sharpen the chisels and hand planes I bought at Woodcraft and eventually Ebay, but then I found Paul’s sharpening videos on youtube. I subscribed to Paul’s Masterclasses and started my journey. Woodworking by hand using so called old hand tools and lost methods are actively alive in Allentown, PA within the US.

Your making me shed a tear paul. I am only 31 but am trying to claw my way into learning more wood working via hand tools I just did my first bowtie inlays using nothing but a backed saw to cut the bowties and chisels. Your videos on YouTube have been a big help . Don’t ask what the floor those inlays looked like. Let’s say I am ecstatic to have placed an order for your router plane kit. The metal/iron casted ones are very costly.

I’m waiting for my router kit too. I’m thinking we ought to have our own web/blog/etc to post our experiences. So far I’ve ordered some timber (enough for 6, surely one will work?) and am waiting for the overseas post to deliver the one kit I ordered.

I like the action siyck figures especially of the person sawing

I second that Samuel, Paul’s comparisons of a dynamic dog vs dynamic person are delightful to my eyes. I felt tempted to print it and frame it (no copyright infringement coming, I won’t 😋)… but this may very well be the sketch which pushed me towards learning to sketch.

I’m capable of some, and find pleasure at technical drawing… move away from straight lines though and I feel the pencil alive and unfriendly in my hand.

Thank you for your mind’s images, Mr. Sellers.

Ka nui te mihi,

Paulo

You speak of visualizing and sketching, and for me, those are two difficult if not impossible things. I took drawing classes in school, but barely eked out a passing grade with more than triple the work that others did. It wasn’t until recently that I discovered the condition called Aphantasia, which I have. People with it cannot see anything in their minds eye. Only black. Occasionally a picture will flash in my mind, but it is never one that was called upon, and just a random image that is fleeting, and gone within a few seconds.

The good news is that I have been able to make many things over the years, but, in order to do so, I need detailed plans (drawn by someone else) in front of me at all times.

Yes, I realise that. I think you may be more the smaller group in not visualising things and your Aphantasia makes that more so. I am sorry if I generalised too much. I do and have known people who said that they just do not have a ‘mind’s eye’ to see with so they must have a picture shown.

Greetings from central Texas, Paul! We miss you!

I hope you or Joseph or someone in your group is collecting all these essays with the intent to publish them in a book. There are so many life lessons shared here that it would be a shame to lose them just as it would be a shame to lose your instruction in working wood. Posterity needs this more than they know! :>

My dad was a printer starting in the second decade of the 20th Century. I remember a pamphlet he brought home titled “The Tramp Printer.” It expressed for the printer’s trade much the same things about how journeymen moving from shop to shop helped spread knowledge of the craft and skill in its execution.

We have lost much. Please don’t your blog among those things.

“Someone asked me how I can justify the price of $6,500 for a single rocking chair when they mostly sell for a few hundred at most.”

Price never has to be justified. The buyer makes a choice. Pay it, or do something else with the money. Nobody is forcing him into the rocking chair.

Thank you for this post, it brings back forgotten memories.

I am less than a decade younger than you. My first industrial job was for a small start up company that was trying to develop and market a dye laser. I was about 15-16 years old and was a go-for (go get this, file this, find me a X…) The company had a small machine shop that made the parts for the various prototypes. The head of the shop was a tool and die maker. I remember the lead engineer coming to him with a design that required an elipitcal hole inside a aluminum block with some crazy precision. He didn’t bat an eye, figured out how to build the part, made the tools that were necessary, and had the part available the next morning. This is long before CNC machines, when drafting was done on a drafting table (yes I still have my lettering set), and computers were something that occupied the basements of univeristy buildings. I will date myself by stating that I went through univeristy using a slide rule. I can still picture that eliptical cutter cutting the eliptical cavity that became the first prototype of the dye laser. I stood in awe of his ability.

Years later, I was a young chief engineer and our firm got its first CNC machine. I convinced them that it was premature to scrap the machine shop. I had a design that we needed to prototype. So I said, lets have a contest. I gave the design to our tool and die maker and the CNC programmer. Lets see who gets the job done first. It will not suprise you that the old fashioned tool and die route got the job done first. Of course the CNC folks told me that they could now make hundreds much faster than the machine shop could make 10.

To which I applied, “but I only need one.”

A decade plus later I was teaching physics at a University. My students had almost no pratical experience building anything, they had a hard time understanding the concepts. So we created a machine shop and had them buiding stuff (like electric remotely controlled aircraft, before the drones were a thing in the press)! Suddently the curriculum became real. They learned patience, concentration, attention to detail, the joy of a job well done, and when to stop and take a break. They learned that one mistake could require them to start over. I would make something and then ask them how I did it. They delighted in trying to figure it out. The physics curriculum came along for the ride! Perhaps the greatest part of their experience was coming to value the experience and expertise of the craftsman along with the understanding of what that meant.

So I look back at the first experience of the craftsman in metal, the tool and die machinist, and the impression he made upon me, and thank him for the lessons in life he taught me. I think (hope?) some of my students share the awe of the craftsman on which we engineers rely. I hope and pray they pass it along to the next generation. I trust and think they will.

Is it lost? I think not, it just becomes less common. Perhaps the detailed skills become the subject of academic works of history. But the role of the craftsman, in whatever the medium, will remain forever. What I hope and pray never becomes lost is the idea of devoting ones life to a craft, whatever that craft may be. I know a few of my students have taken the challenge to devote themselves to a profession/craft.

All is not lost! The future will be different, but the role of the craftperson will always be present. Keep the faith!

Thank you for your work and thank you for lost memories recovered.

David Larrabee

Well I am not sure if it applies here but I do own a cell phone. It is my only phone. However, I do not use it for “data’, I simply make calls and receive them. I have an email for anything else. And I do love using hand tools for all else. I am so glad they haven’t digitized cooking it still relies on a good sharp knife and basic skills.