Expect

I often wonder why we sometimes think the way we do. I’ve mentioned this somewhere before and should mention it again. In a class some years ago in the USA, an exasperated man said, “I’m an intelligent being, I have an advanced degree and I am a problem solver heading up a team in IT for IBM. How come planing wood with a hand plane and cutting square with a tenon saw seems so impossible to me? Every cut I make tilts away from the line and the square!” It’s not an unusual question. Whether it’s related to the kind of intelligence he excelled in I don’t know. Intelligence translates to work in many different ways. I saw a biophysicist dismantle a biro pen once and he couldn’t put it back: a seven-year-old took over, loaded the pen replete with spring and clicker and the pen worked fine. A consultant paediatrician was working with parents and their child for autism when the parents tried to stop the child from messing around with an examination bench in his office. The doctor, focussing on the parents, said he didn’t mind. After ten minutes, the consulting table went up and down having stopped working some years before. “Wow! Look at that,” the doctor said. “We’ve never been able to get that to work and he just did it.” We all have different gifts, you see. It’s not so much about how we perceive our own intelligence so much as how it manifests in our individual lives.

Since age thirteen I have always been able to use a plane and a handsaw. It was in school though that I was considered one of the “thicker kids.”. Of course, I wasn’t. Wherever I was at that time was mostly where I chose to invest my time, interests and abilities. When I place my plane on wood I expect smoothness to occur beneath the plane and I expect the wood to be flat and straight when the final stroke concludes the work. If I cut out of square with a saw or plane, it is simply because I was fully cognisant and allowed it.

Yesterday I made two doors using hand tools and that included planing the wood foursquare and straight using hand tools and a bandsaw for resawing. The doors comprised mortise and tenons throughout, some lamination work and also running grooves to receive the door panels. That was four hours of work. When the frames were tapped together they were exactly to size and with no twist in them. Reading the grain comes with time. We can talk about ‘cathedrals’ in the grain pattern but often we still cannot tell whether a layer of growth is over or under and when the plane hits the surface a tear a millimetre deep has ripped into what was reasonable good before. Sound familiar?

My work has trained me to look into the grain differently. Of course, experience makes a big difference. What helped me the most was the challenge of working with George. There the oak lay in silence on the bench between me and George. It needed planing and was still rough sawn. My job now was to tell George which direction to plane the wood in before he lowered the plane to task. I was to look at the wood, the grain, and tell George which direction the grain would plane best in. In general, I could pretty well get it after a few hours. Why? If I got it wrong, George made me plane out the torn areas and the whole board plus the next board whether I got it right or not.

What can you expect? Well, aside from the cathedral pattern and looking on an adjacent face for the growth ring layering, there are more compact and localised elements acting as tell-tale signs for us to look out for and follow that I have never seen mentioned and yet speak so loudly to sign our direction to plane in. Often the result from rough sawing on the bandsaw and with every kind of handsaw too gives us clues aplenty. These clues are often tiny, barely discernible and yet when we see them, they stand out like a neon sign saying, ‘Not this way!’ and ‘One-way only!’ What are these signs? It’s the tiny surface fuzz, the splintery corners and then some indescribables that defy naming when we trace our fingertips sensitively over the wood’s surface. And, if we have calloused hands, then pulling a soft and fluffy cloth lightly in one direction then the other will also tell us which way the grain runs and whether it is in favour or against us

I knew my wood had underlying issues as soon as I saw it. I can show you a couple of pointers but ultimately you will need to look more deeply to better understand your wood in your situation. Ripping through the area of concern confirmed it immediately. See how in the picture above the grain curves around what was once a knotted area.

.

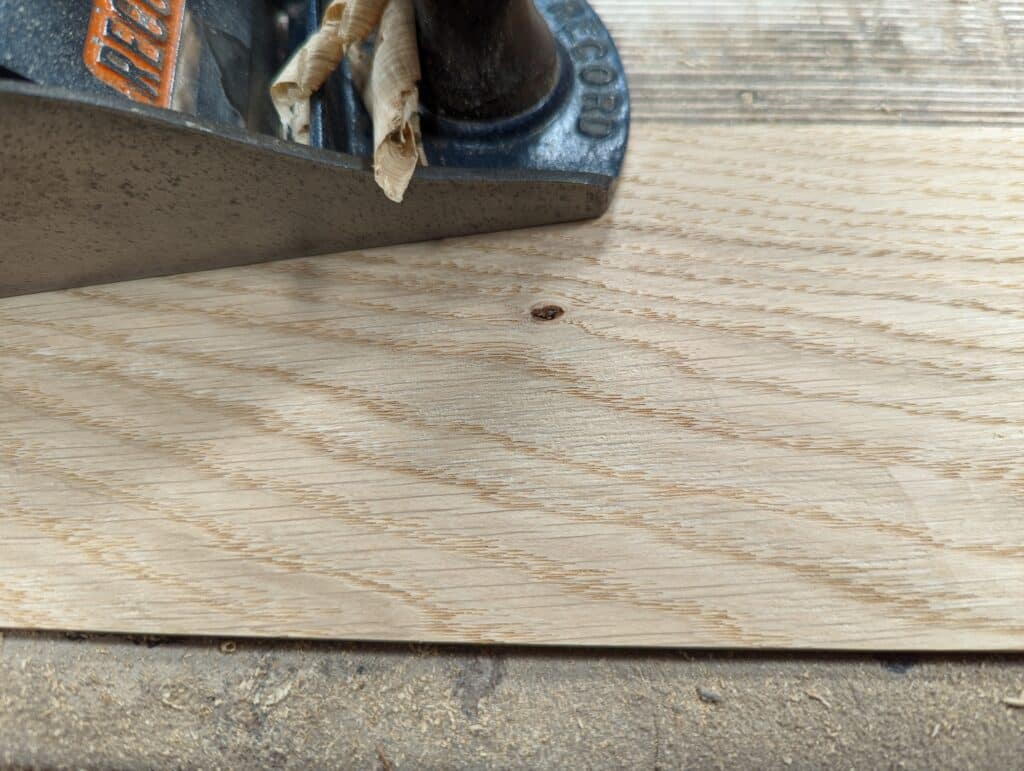

Planing into it immediately tore the grain a plane-swathe wide.

Planing from the opposite end corrected it on one side of the area but tore the wood in another.

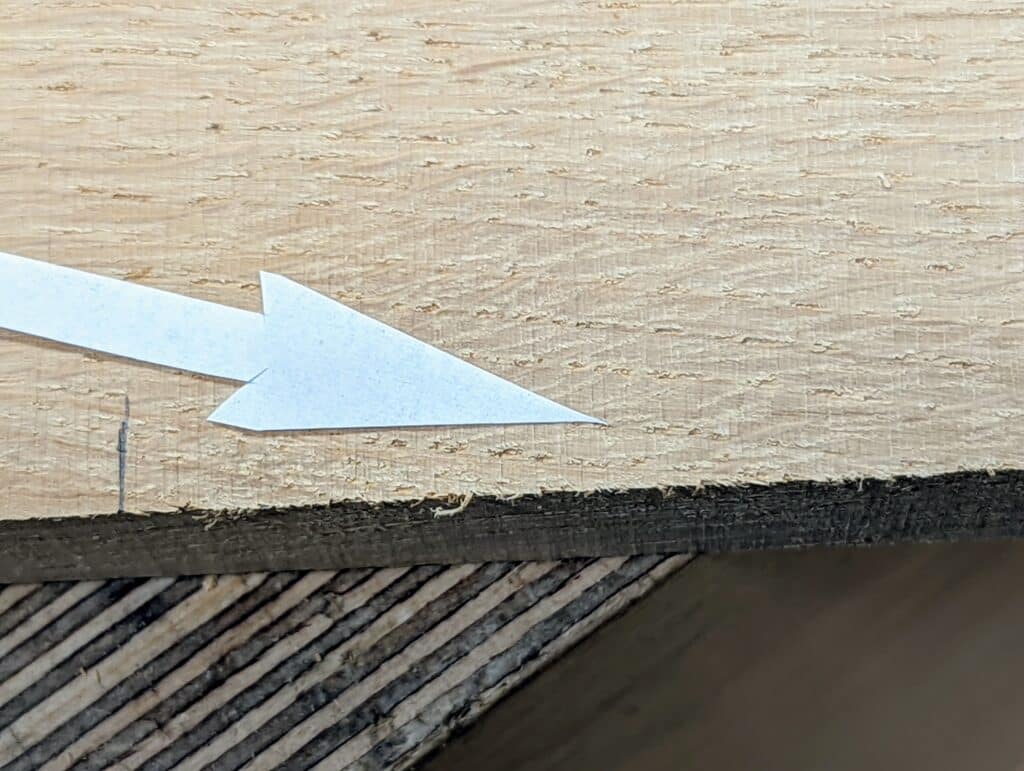

So having seen the surface difference did indeed tell me this would be difficult to plane, but there were other signs there too. Enlarging the image you can see beneath the arrow point tiny fractured fibres along the corner. These fibres tell me which direction to plane in; in the direction of the arrow. Then again . . .

. . . Planing from either end results in tear-out to both sides of the problem area in this case.

So, between the two pencil lines, I must plane in the direction of the two arrows but if the plane lands and starts cutting before that central knotty section the grain will tear out. . .

. . . this area must be planed the other way.

Notice the corner fraction and the direction of the fibres this time. it’s often very subtle but it is always there. Pull your fingers gently on the corner one way and the fur will be the same as stroking the cat backwards. Pull the other and the wood will purr. Look now in the surface above the corner, see how these fibres are raised in a certain direction. These

The intensity of planing into rising grain, against the grain is the term, can cause an equal level of intensity in staggered cutting as the plane stammers into its negotiation. Once the plane passes over the midway point the grain planes smoothly.

Not so easy to see or determine is the layering of the grain that also shows grain direction which tells us which way to plane. In the picture above I have marked the bottom or lower grain level and the upper or top layer. the arrow indicates that by the layering alone we can only plane one way, in the direction of the arrow. The picture below shows a smooth surface

In the next picture below I planed in the opposite `(wrong) direction and the grain tore.

From the opposite end of the board, the layers of growth rings are affected by the awkward grain area centred. I have pencilled in the high and low layering which in this picture is more obvious. the wood must be planed in the direction of the arrow.

Below we see the conundrum. Plane one way and one section is smooth, while beyond the midpoint it is roughened by the plane cutting into and against the grain. Plane the other and the exact opposite takes place.

In this picture I planed almost up to the midpoint indicated by the pencil line and at the end of the stroke, I lifted the heel of the plane before it went into the rising grain that would tear had I continued into a through-stroke. So the wood is smooth to there.

In this picture above I planed from the opposite end and direction into but just shy of the midpoint indicated by the pencil and again lifted the heel of the plane off before it went into the rising grain.

Now, to negotiate that unplayable section, I switch to the #80 cabinet scraper.

And the end result is a level and smooth surface all the way through.

Had I not been always looking for potential in wood, there would have been many a time when I would have missed what could have become. Above is the result of persevering with the wood as you see in my considerations above steps to reach a finished piece. Whether a panel for a door or a clock, the end result takes the very ordinary and plain to be extraordinary and great gain, potentially resulting in a higher price but without much if any extra work.

As with everything practice, practice, practice and practice again. I have done this since subscribing to your informative page with bad, bad , bad until I got it right right right using snippets of advice on all things wood. I feel so confident now with using hand tools I feel like a pro, well semi pro.

Excellent article as usual Paul. I can’t count the times my #80 got me out of trouble.

Dear friends

As usual, these wonderful article about shared experiences of life and craft leads us towards the questions of our own abilities to deal with handwork, it’s a real pleasure in spite of my mistakes.

Nevertheless beyond the philosophy of furniture making from different kind of woods, I would like to send my best gratitude to Paul because I received his fantastic book.

Essential woodworking hand tools.

Great help!

Thank you so much for the book, YouTube, and what you write on your website.

My only deep regret is not to have attended your courses.

All the best.

Matthieu

Wow, is that joined board (last image) is gorgeous! I’m curious if you’ll fill the knot hole or leave it. (Personally, I’d leave it if it were a cabinet door, it’s so interesting.)

I’m thinking some kind of clock with a swinger of some kind, wall-mounted, other wood in it too maybe. Just need a great movement for it, not a cheapo.

A semi-related question.

How has the water borne sealer on your plywood benchtop held up so far?

Brilliantly. Perfect.

Almost insane. Use the cap iron on the plane and disregard grain direction in sizing and finishing until the very last stroke. Its free to use and far more efficient and effective.

Hi David. What do you mean by “use the cap iron on the plane”?

I think he means any grain difficulty can be addressed by setting the cap iron as close as possible to the cutting edge which can help in some grain patterns but not all and not always; and of course, additionally, that my suggested solution is, “Almost insane” which of course, it’s not. It’s much faster and easier to do than resetting the cap iron that’s for sure. It takes only a minute to do.

That seems so dismissive it makes me almost dismissive of the comment.

Paul do you expect perfection in your work? Or do you have allowances and tolerances in your work? Would you say there is a balance between being too pedantic and precise that is slows production and that you need to Instill an element of balance to this idea between getting the job done but also caring for quality but not being too pedantic and perfectionist of?

Perfection is often the illusion of the proud and those that say “I am too much of a perfectionist.” As a maker selling, life is very different than a maker who has a lifetime to make one thing. I recall a critic saying how his dovetailing was better than the man who made a very nice cabinet in a stately home because his saw ran past the lines. I pointed out that the maker in this case the maker probably had to dovetail six drawers and fit them into the openings in a day or two or another maker would soon be found to replace him. I then asked him how long he took. I see some flaw in something I made but often, once the saw cut is made it is irreparable and I usually let it go unless it is a focal point. One small gap on six dovetails in a corner of a drawer is of minimal consequence beyond a minor disappointment. I just get on with the job. I think you phrased it perfectly, “caring for quality but not being too pedantic and perfectionist”

I have one of those cabinet scraper things and for the life of me I can’t raise a burr on it’s blade. I can raise a burr on other scrapers though. Get the hook raised. So I’m not sure what’s going on there. I need to give it another go.

Here is a link to our free common woodworking that will give you the core information first. And then my video showing the best way to file and hone the cutting edges before turning the edge. I think reading and watching these should help.

How to saw straight? Start by writing out the instructions for riding a bicycle. Be sure to provide details on keeping balance, gyro effect, and inner ear.

Then just saw another half inch off the end of the board. I can do it now, and it sure seems easy. For about four years, it wasn’t.

I forgot the single most important and effective thing I learned. I made Paul’s oiler can, filled it up with 3-In-One, and set it on the bench. At first I only oiled the teeth. Bad idea. Then I oiled up the whole saw. All over both surfaces. The change was immediate and amazing. It also “taught” me the sweet spot for feeling the movement of the saw.

Perfect explanation. I have met this problem some times (havent done so much of woodworking yet, but watched many of your videos) and wondered how do you solve this. Thank you Paul for sharing this.

I appreciate this blog; it is where my reality of planning lie: dealing with multi directional wood grains in on board or boards I’ve laminated together (making planning even more difficult). Tear-outs are becoming smaller, but I’m still shooting for smooth, like glass, boards.

When I watch your videos, you make it look so easy, due to your experieance and the boards you’ve selected. It would be nice to see you dealing with multidirectional planning some time.

I appreciate you influence and encouragement. It has helped me slowdown and focuse on each step of my projects and see where I’ve improved, all be it, minor but rewarding. “Progress not Perfection” as they say. Thank you.

Over the years a number of people have said to me ” I wish I could saw straight or square like you do” My own skills developed working with the men at work who expected that I would saw streight/Square. My single best tip is to ensure you have a nice sharp saw. When I look at some of the saws I see people trying to cut with I’m not at all surprised they can’t saw a straight line.

On the other hand . . . I don’t really see this as a general issue as almost everyone I know and have known for three decades to date uses throwaway saws with non-resharpenable teeth. That being so, the main issue is that push stroke saws have too wide a kerf giving excess allowance in the cut that then leads to swerves and curves away from the line.

Lightbulb moment here with your answer, Paul:

when using a non-throwaway saw, keep the saw teeth set just ‘opened’ enough to scarcely ease the plate down the cut, but not wide enough to let said plate wallow from side to side, thus allowing it to get away from the line.

So gently set first, then sharpen, maybe?