I remember

I remember Mr Cheapy arriving in his blue minivan, and I mean the true Mini minivan–two seats in the front, touching both door windows with your shoulders, and the meter behind being a flat-floored, tin-sided van with no frills, padding or anything else. It was always loaded with tools, many seconds quality with minor defects and I’d ordered my first Stanley #4 the week before for this Tuesday delivery, the day he always came each week. I watched as he checked down his list and lifted the orange box from several others stacked and ready for delivery. He slipped the box into my hands along with a Spear & Jackson tenon saw, a Stanley marking gauge and a Stanley combination gauge, all Sheffield made. Mr Cheapy had a pickup Mondays where he visited different Sheffield makers and suppliers and bought tools for him to sell to different trades, mainly woodworking. Tools were generally a third cheaper than shop prices and you could get what you wanted even if you had to wait a week or two to get them. I couldn’t wait to try them. These were my first ever tool purchases. George had directed me. He stood smiling as I approached the bench. “Go on then, try them!” He rolled a two-by-four towards me and I tightened it in the vise.

Eye-balling the set for depth of cut was new to me. I’d done it some but was far from an expert at it. George watched me but left me to it. The plane jagged and jarred into the wood and left a perfect washboard finish on the wood. The wood staggered, the plane staggered and I staggered and George just laughed. It was then that the best lesson of my life ever began. In under an hour, my plane worked like his but minus skill. In his hands, the handles were dwarfed. He owned a #4 1/2 Woden, less common than Stanleys and Records, maybe a touch heavier in the casting. Until this time I had been borrowing his Stanley #4 and I’d got used to that as it was well broken in and had the smooth action of a well-used tool. It’s not at all unusual for us to cling to our first tools . . . and our seconds and thirds too.

George told me to take the whole plane apart and then put it back together. “Every screw, nut and bolt off first!” he said.

The parts were all somewhat greased and the whole plane had been wrapped in a greaseproof wrapper with the name Stanley printed all over it in the brand logo. I used steel wool and oil to cut the grease and wiped all of the surfaces with a rag. It’s hard to find the words for how I felt that morning as I lay the bits onto the rough benchtop. Sawdust soaked off the newly oiled surfaces and stuck to the plane iron and the cap iron, the plane sole, frog and screws. This reductive approach consumed my whole being and my confidence waned markedly. It’s an approach I have used throughout my life, dismantling and reducing, its how we best learn about how things function, how to set things and such. Machines too. Living in near wilderness places (exaggeration) in pre-online days, dismantling a bandsaw or a planer was most essential. Realigning mechanisms, replacing parts, bearings and such, was essential– it all started with a #4 Stanley bench plane.

To dismantle a plane is not particularly complicated but it does take something to believe in yourself. No cell phones to take pictures with, no Googling, just a pamphlet with a schematic and a low-grade print job. In my case, I had a George. All I needed.

When I began to teach others some 30 years later, I used the same system. I told 15 students to take their (my) planes completely apart and then reassemble them or sometimes they arrived to dismantled planes, I gave a demonstration on dismantling, assembling and setting up the plane and they followed suit. These planes were already fully settled and functional. It wasn’t a restoration class but a familiarisation class. When I learned about various firearms it was the same. The best way to understand guns is to take them apart., clean them, oil them and put them back together There is more to owning guns than shooting them.

It was surprising how much the students knew and got things right in these hands-on workshops but then how many just got things wrong too. The most common mistake for planes was fitting the cutting iron to the cap iron the wrong way around. Some also tried installing the whole cutting iron assembly upside down. With spokeshave blades, it was the same. But I understand it. If you’ve never seen it, how would you know and why wouldn’t it work?. Same with planes.

The obvious things are easy to remember. When George showed me the distance the cutting edge needed to be in relation to the cap iron (chip breaker USA, for some unknown reason), he wasn’t showing me one thing but two. First, the distance, but then without words, the way the cutting iron faced the cap iron. Holding two parts in your hands switches on all of the synapses for most people. Tripping the switches that link everything together is mostly a one-shot lesson requiring no more reinforcement. “Anywhere between 1/32″ and 1/16” George said. “On a wooden plane it’s more.” he went on.

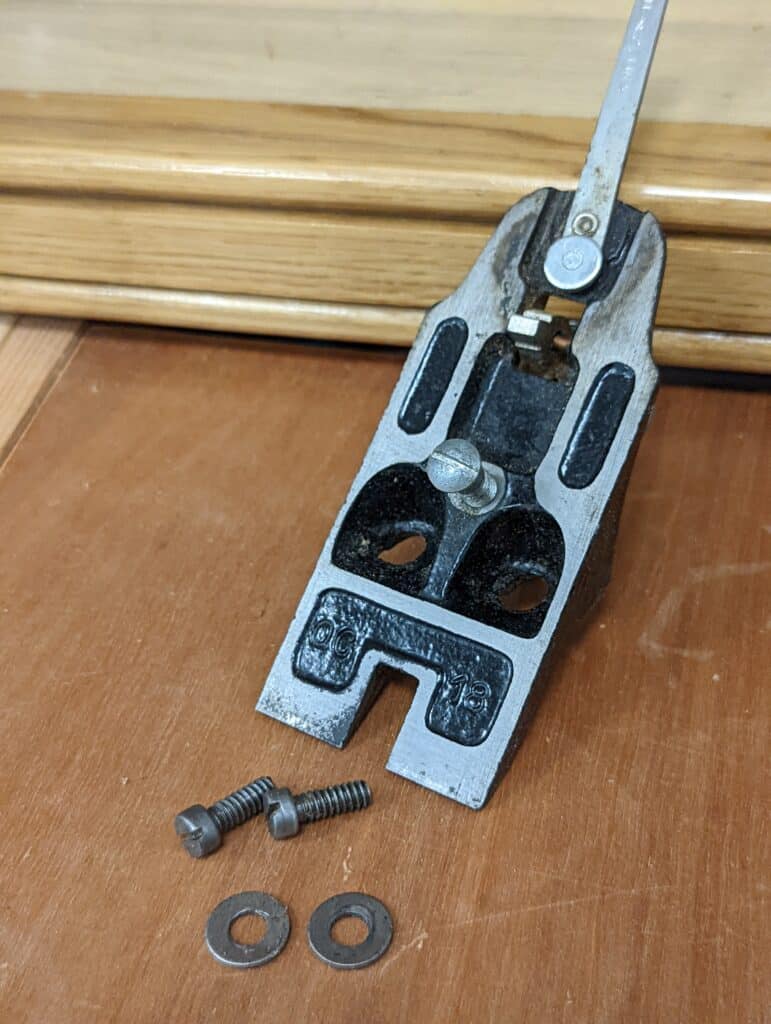

Reassembling the components was pretty obvious in that there was but one frog (the cast angled block that hosts the cutting iron assembly and lever cap and central hub from which all of the adjustments for the blade alignment and set take place) that could only fit one way into and onto the sole and the only component that has two identical setscrews with two washers for securing to the inside of the plane sole. Then there is the ‘U’ shaped slot for adjusting and setting the frog distance controlling the throat opening which had its single setscrew through into the frog and one into the sole for adjustment back and forth, so, once again, an obvious placement. Once these parts are bolted on the only other attachments are the plane handles fore and aft. George had me remove both of these too. Any other components revolved around the cutting iron assembly, which were all bolt-on components allowing for immediate quick-release for sharpening.

I should point out the absolute flawed thinking people have about BedRock bench plane soles and the main reason for users rejecting the BedRocks both when the design was released to the market and throughout the ensuing decades to follow. You see, the BedRock plane was less successful and for good reason. Whereas some say it was primarily the cost that put craftsmen off buying it, that was not the case at all. Four main reasons defeated Stanley in selling this plane over its Bailey-pattern cousin. One, the weight of the plane was heavier and especially was this so over wooden ones. We tend to believe that all metal plane versions were superior in several ways to the wooden ones commonly used for centuries but they were not at all. The fact is, woodworkers at the highest levels of craftsmanship produced some of the finest work ever produced using wooden planes. Two, and the main reason, was that when you adjust the frog on the BedRock plane you automatically changed the depth of the cut one way or the other. This is because the frog is set on an inclined plane. Two opposing inclines allowed the frog to slide up or down to open or close the throat opening for an ultrafine distance setting no one needs. The main advantage supposedly is that you can set the throat opening without loosening the frog from within the body of the plane but that alters the depth of cut and so markedly diminishes any and all advantage this feature might offer because we change the throat opening so rarely, and I’m talking possibly once every five years if that, there is no advantage at all. In actuality, you can set the frog of the Bailey-pattern planes without removing or loosening the frog of the plane anyway and it will not alter the depth of cut, you just need to know how. The third reason was of course the added cost over and above the Bailey-pattern plane. The very best of basic planes from the Stanley stable of the day remained the basic #4 plane by Stanley or Record which outsold the BedRock many times to one. It is still the best all-metal plane out there bar none really. so no one should ever feel that buying the less expensive lightweight model without the fancier frog produces any lesser quality of workmanship. It does not.

There was and still is much snobbery surrounding metal cast planes. I knew men in my youth enjoying a post-war period of more plenty in peace who from newfound wealth spent on planes more for status than functionality. They just enjoyed owning a Norris or a Spiers, a Mathieson or such that they rarely if ever used just for the joy of owning the greater scarcity rather than this or that being a better tool. Today’s snobbery might be more from ignorance and false belief and it can be from simply owning something that is just well-engineered. My tackling these issues more vocally and from a platform that influences is to counter the false information that this or that £300 plane performs better than their less expensive counterparts. We should never confuse less expensive with cheap and neither should we confuse a lower level of engineering with poorly engineered leading to lesser functionality. I like the minor take-up of a couple of turns on my depth adjustment wheel and I have owned planes with lateral adjustment levers that flopped from side to side like a happy dog’s tail. neither affected the plane’s performance and I used them for years. So in our present age, we generally find marketers dissing one tool purely to sell another. Every maker of fine planes tells its buyers that this nor that doesn’t happen to their planes because of something they did to prevent it when in fact the this or that never happened in the first place. This is a basic tenet of sales and marketing. I’ve met them at every show I ever went to and seen the blurbs in every catalogue. Please remember that ALL online sales outlets are good at selling and most selling is about being confident about knowledge. It does not mean they have anything more than head knowledge. Experiential knowledge is radically different and it doesn’t happen by just using a tool for an hour or two.

I see nothing wrong with wanting a nice-to-look-at, well-made woodworking plane. As I have illustrated, the men I worked with kept their better planes under wraps and mostly out of sight year in and year out. The one plane-type hundreds of thousands of full-time makers relied on for a full century and more was the Bailey-pattern bench plane with the internal mechanics to each plane line being identically interchangeable so that one or two central control units could fit into planes of different lengths. `very innovative for its time and good for manufacturing costs, mass-making, etc. But people owning a better-looking anything is often to be more status conscious and not much deeper than that, that will never end, and if anything it is getting worse today than it was in times past. People involved in manufacturing and selling planes are excellent marketers and of course feeds the supply and demand needs of any consumerist society. With the minimalisation fo and in some cases the elimination of true craftsmanship in furniture making and woodworking generally, there is only historic works of reference to draw any comparison to. We’ve lost the middle generations of almost a century that stood testimony to true artisanry and we have been left with untruths standing in truths stead that lead to greater confusion rather than clarity. Owning a fancier plane with tighter tolerances does not automatically produce higher levels of artisan quality but it can be inferred that and dare I suggested by manufacturers that their heavyweight plane can give the results you wasn’t for superb artisanry. It is mainly an artificial impression when you compare the work of two furniture makers making the same project with a Stanley and a Norris, Spiers, Mathiseon, Lie Nielsen, Juumma or whatever. The outcomes will likely be identical.

The way to test out our preference for a particular tool is try them out side by side for a period of a few days or even longer. Making sure that they are well adjusted, sharpened and set well, simply use them as much as possible and see which one or ones you lean towards as you work.. The one you reach for the most will likely be the one your body and mind are telling you you feel the best about. This is a good test for any tool. Anyone purchasing a half-decent Stanley or Record plane secondhand can fettle it in an hour and own a plane for under £30 that will outlive them if they use it every day throughout the day for a hundred years. So much was the humble Stanley plane disregarded 12 years ago that you could pick one up on eBay (as I did) for around £1 with a shipping cost of £2. We have reversed that directly through our output simply by telling the world, “Hey, hang on there just a minute!” and then showing people why we got what we did with the cheapest plane on the block. Subsequently, the price has levelled out at somewhere between £20-30 today on e`Bay and elsewhere. I just bought a very nice Record #4 for a lowly £28.50 with free shipping. The plane looks as though it was sharpened just the once in its lifetime once and used until it dulled, I expect. It’s a seventy-year-old model with no issues apart from some very mild smattering of surface rust.

My ‘George’ was my dad, an apprenticed trained carpenter and joiner. I can remember when I was in my young teens ( I’m now 68) dad was working on various sites and joinery shops . When the question about what I’d like to do after school came along it was always ‘ be a carpenter. ’ ( my younger sister wanted to be a carpenters apprentice as she like the curly shavings when my dad was working at home) . Dad would reply I’d rather you have a job in an office or something where you weren’t sent home if the brickies hadn’t got on far enough for the carpenters to be needed , or the timber was covered in snow etc etc

I didn’t think much about what tools he took to work but now when everybody can afford to buy more or less what they want , and when , it comes back to me and I realise how little he needed to do his job, very well. He had a brown canvas bag with rope handles the beauty of which was that when put down it laid flat and you could see everything that it contained. No searching for bits in the bottom of a plastic tool box. I can remember him carrying a hand saw, tenon saw, a roll of chisels ( half dozen at the most) , a brace , roll of bits and an awl and few other bits and bobs, claw hammer, pin hammer, a Stanley No 4 , coping saw, sliding bevel, combination square , one Norton oil stone , various rawl plugs, plugging chisel etc . His father had bought him the plane when he started his apprenticeship along with the combination square, Stanley chisels and what ever else was on the ‘ needed’ list , he used most of those tools , plane included, until he retired and then until he passed away at 80. Coming home after each day the plane and chisels were sharpened , and the saw touched up as needed , this before he sat down to tea. it was second nature so no big deal. Everything then wiped over with an oily rag .

It had the frog replaced ( the threaded hole to take the adjustment wheel rod had stripped) and I don’t know how many irons he’d gone through. I don’t think I ever saw him adjust the mouth ( probably did but very rarely) . He worked all his life with those minimal tools earning money to support a family of 6 . He couldn’t understand why I wanted, or needed a shelf full of various planes , rolls of different chisels, etc

I now have his tools and that plane feels so much nicer to use than any other of my much more expensive planes . He never had exotic steel irons just the standard Stanley one, which he always got to a super sharp edge with his one oil stone. Whilst I’m not saying that there’s no need or it’s not nice to have shiny new tools , it’s far better, at least initially to have a decent plane and understand properly how it works.

Regards, Steve.

Steve, thanks for these thoughts, very grounding, and reminded me of the wonderful uncle who gave me my first bag of basic tools, almost identical to your father’s, when I was fourteen. Priceless. I owe my current wealth and skills to that kind, unassuming man and had the privilege of speaking at his funeral and telling the family what his action meant to me now in my retirement. There are often giants walking amongst us that we just don’t see…

Thanks, dear Paul for that in depth discussion on planes and surrounding issues. I bought a used Record Nr. 4, did the treatment you show in the video and it works perfect. And totally true, after doing that you know the plane by heart Also bought a Hock blade to prevent chattering (just kidding but these as the Ray Iles work very well). However, I also bought a Lie Nielsen bronze Nr. 4 as a present to myself for successfully finishing a large-scale project. And indeed, I use it less than the Nr. 4. However, still I would disagree on some points you made RE new planes, marketing.

If you go e.g. to the Veritas Nr. 4 site, they plainly list the features. No marketing whatsoever. Lie Nielsen claims “Our Standard Bench Planes are based on the Stanley Bedrock design, last produced in 1943. In their golden years, the Bedrocks were the top of the line. They featured a fully machined mating fit between the frog and body, and the ability to adjust the mouth opening from the rear without removing the cap and blade. Lie-Nielsen Bench Planes include these features as well as a Bronze cam lever cap, lateral adjustment, and spinwheel blade adjuster.” They do not claim to be any better but in a good tradition while your comment RE the basic design still hits the nail.

My principal disagreement however would be the following. What I all bought vintage planes only? We would have no producers anymore. Furthermore, Nr. 4 may be the bread and butter one that generates surplus for designing new stuff e. g. the low angle Veritas smoother you use. Often you rightly complain that good toolmakers got out of business. I fear woodworking handtools is not a mass-market anymore and will never be again. They have to sell lower amounts at higher prices. So, I do not mind if people grab a LN or similar and have a high quality tool that also lasts a lifetime. It adds that we still have a couple of small high-quality suppliers. But I would definitively concur that an old Record or similar will yield the same results, probably also less resource intensive.

Best

Christian

Leaving for the lumber yard for getting pine for making the Shaker bookshelf you introduced some 8 years ago.

{“Anywhere between 1/32″ and 1/16” George said. “On a wooden plane it’s more.” he went on.}

The extra little gem in the text.

Could you explain why more on a wooden plane?

Because of the geometry of the shaving escapement?

Dismantling the tool to understand how everything works together. Great advice. (usual practice though for some of us with a technical background).

I read a lot on line about reasonably priced old Stanley and Record planes but my experience is that these prices are about as likely to be had as is seeing a unicorn in my yard. I recently moved across the country and the movers “lost” or stole many of my tools that I have had for decades, some that were handed down a generation or two. The heart break of losing the irreplaceable connection to the past coupled with unavailability of reasonably priced old tools really sucks. Pardon my French.

I assume from your use of the word yard that you are in the USA. Yes, some people there do ask silly money as they do here but here in the UK there are about 150 for sale daily that will sell for well under £30, I just saw a very nice clean #4 for £20. Shipping will cost the same or a little more to the USA so if you can buy a decent Stanley of around £60-70 that’s still a decent price for a lifetime tool. Watch for equally silly terms used like ‘Unmarked Stanley’ or wrong blades etc.

I’m sorry to hear about the loss of your tools. Reasonably priced older tools can be found but I find it takes patience and being vigilant when searching on eBay etc. I picked up a decent old record no.4 for £10 plus postage on a late night ending auction on eBay, most sell for £20-30 as Paul says. I just happened to be only bidder which doesn’t happen very often in my experience. I’m not a huge fan of auctions as I find it too easy to pay too much, but finding decent lower priced buy-it-now listings are scarce.

Kind regards,

David.

Hi Paul.

Can I ask, when replacing the frog, to the body of the plane, what is the measurement from the opening in the sole of the plane. I was a bit like yourself, as a youngster I would dismantle things to see how they worked, had a lot of things taken away, as I was thought to be distrutive, may be it’s because I couldn’t get them back together. Really appreciate your blogs.

Kindest regards Geoff Maddison

I didn’t have anything taken away, Geoff. Not sure where that came from. Parents totally encouraged me to be creative. There is no measurement, Geoff. The throat opening can only be as wide as the fore-edge of the frog aligning with the fore-edge of the plane sole throat opening’s back edge. This is the best position for the frog in general and rarely if ever will this need to change. Because the back of the cutting iron hits the foreedge of the sole of the plane, moving the frog back to gain a wider opening does not work. Going further forward closes down the throay=t but this then restricts the shaving exit so best is as said.

I too was discouraged by parents from taking things apart for fear I would break something or didn’t know what I was doing. I always felt a need to find out how things work.

Back in elementary school, I did a book report on Walter Chrysler. The thing I still remember was that when he bought his first car, he towed it home with a team of horses, put it in the barn, then proceeded to take every piece of it apart and put it back together. Upon final assembly it ran, but he had no experience driving, and promptly drove it into the ditch. Then he proceeded to found a car company.

I have three No.4 planes, two Stanleys and a Record, all bought for next to nothing at car boot sales a few years ago. After fettling all work well and have been used regularly. You’d think they’d all feel the same, but they don’t. I’ve got used to the way each of them feels and invariably choose one of them over the others to use. It’s them same with saws, of which I also have a selection mostly sourced from car boot sales. I tend to reach for the same ones over others, just because they feel right. I should add that it is only through use over a period of time that the differences in feel have become apparent. It is amazing how the body and mind can sense such minor differences in tools that on the face of it should all be the same – and I do love the fact that it is so!

Please continue to recount your relationship with George in future posts. He is a treasure. Your reminiscing is a tribute to his legacy. I longed for a mentor like George when I was in the apprenticeship “stage” of my career. In the years to come your former students will write their blogs and recount their tutelage by you on their YouTube channels with the same respect and affection. In fact, some already are. Well done Paul Sellers.

Well done again sir. Love the stories that include George. He sounds like he was a good man.

Also loved your comment about the lateral adjuster wagging like a happy dog’s tail. I still have my Dad’s old No.4 with a broken lateral adjuster. All sharpened up and has worked well for me for years. And yes, it is almost purely sentimental as I have a better No.4 that is set for very fine work.

And no apologies for my sentimentality either. My Dad’s tools for me are a real connection to him as he has been gone for so long.

Thank you for you blog posts. I really appreciate them.

tx, Ed

Thanks, as ever, for sharing your thoughts.

It strikes me, Paul, that as George was your mentor, we all have much to thank him for!

I particularly like your description of a lateral adjustment lever that “flopped from side to side like a happy dog’s tail” because my old #5 (1899-1902 vintage) does just that. It makes no difference at all, and the plane still performs beautifully. I have (and will continue ) to resist the temptation to hit the rivet in an attempt to tighten it.

Great article – thanks.

Regards

Chris

Why do you need more distance between the cutting edge and the cut iron on a wooden plane?

Wasn’t the two piece cap iron part of the Record design? Since it is awkward or even impossible to strop with just the bottom half of the two-piece cap removed, I find it makes sharpening harder, not easier.

“Owning a fancier plane with tighter tolerances does not automatically produce higher levels of artisan quality….” Indeed, and that, I fear is partly because “artisan” begins with “art,” not with tool. There are so many technically-good pieces that needed more time in the mind and have too much focus on joints and joinery rather than emphasis on the overall artistic merit of the work. On the other hand, when the art is good, the piece can stop us in our tracks, capture our attention, shift our mood, and we don’t even notice the technical faults or wear of time.

The two-piece cap iron doesn’t get in the way as the back of the cutting iron does not need perpetual stropping once it’s initialised. In other words, the cap iron is stropped on the flat face and because this face never wears it can be flattened and polished out to the same matching standard we require of the bevel and once done all future abrading to attain a cutting edge is done on the bevel alone so we abrade and polish out the bevel to get down to a fresh cutting edge and then a single pull on the flat face away from the cutting edge snaps off the burr and we are back in action by simply replacing the clip in part to the Stay-Set cap iron again and installing the assembly.

I let AN Other use my Stanley no 4 over a weekend once. It came back with a broken rear handle. Not able to be glued.

One of the other chippies on the site, gave me a ‘Rapier’ brand plastic handle.

Now, 46 years on it is still in place being comfortable, and nothing wrong with it.

I own a Record no 4, and a Stanley 4 1/2 (low bob front handle from my grandad) using them for selected tasks. All are great.

Take care.

Make a poor man’s best plane in the world…out of wood please. All ur wisdom poured into it.

Paul. Thank you for this, such a sensible view and appreciation of life, skills, and tools, born of effort and quiet diligence. Thank you for showing that it’s not what we have but how we care for it and use it! This frantic, name-driven world needs to slow down and get real, maybe then we will heal the troubled minds we see so often. Never has there been such a need for quietly spoken care and advice such as you give, to show that we can make, build, grow etc with such basic items, and then thrive when we see the results unfold… Keep at it!

Mr. Sellers,

I know its been a week since this was published and I and several others have commented on various and sundry things, but (yes, “There’s always a ‘But'”) something you said: “In actuality, you can set the frog of the Bailey-pattern planes without removing or loosening the frog of the plane anyway and it will not alter the depth of cut, you just need to know how.” , has piqued my curiosity.Now I happened to be blessed with a mechanical mind. As a child I could take Mattel wind-up toys (the ones made of stamped metal bodies held together with tabs and slots – remember those?) and put them back together with fewer parts but they still worked. My parents were always wondering “How did he do that?”. Anyway, your statement that the frog screws don’t need to be loosened in order to “Set” the frog at first got me to wondering if instead of cinching the frog screws as tightly as possible, you left them just snug enough to keep the assembly from normal planning pressure, but still movable with the adjustment screw. However, that goes against all advice I’ve ever seen written and/or heard, which is to cinch them down tight. Of course, most people who want to move the frog want to move it forward to close the gap and it occurred to me that that could also be accomplished by adding a metal shim of proper shape and thickness between the blade and the frog. Any glimmers of enlightenment to cast on this conundrum?