BedRock or Bailey-Pattern throat openings

My task in reviewing issues woodworking is mostly met very favourably. There is more to my reviewing things than simply looking at things critically, that’s less than helpful, searching through texts for truth though often reveals the attitudes of makers as much by what they miss out as what they say. I think it’s true to say that manufacturers on a global scale mostly make tools and equipment to sell and never to use. An engineer stumbles across something that could be made better, gives it some thought and, hey, he makes the thing better. Equally so, many a good maker has been put out of business by a manufacturer cutting costs and offering something lesser but looking the same at a lower price. Vises would be a good example. Record vises of old, quick-release ones, could never be beaten. The company was taken over, the vises were dropped and Indian and Chinese imports were brought into the market to replace them. The quality has never been the same since. A mix of manufacturing/marketing strategies came into play. Distributors would pay only this or that price and the makers made accordingly. Vises have never been the same since.

My advantage through the decades has been that I not only used but used as a full-time furniture maker and woodworker earning my living and supporting a family from a single income. That’s what I’ve done through a complete lifetime to date though my kids have long since flown the coup. This alone gives me a different perspective than others. Additionally, I don’t sell tools, take tools or equipment as a kickback and neither do I take any sponsorship. I’m my own man. Doubling or tripling my income for almost no extra effort is of no interest to me. I want clean output.

In my work, I frequently encounter ambiguous statements, untruths, and meaningless statements further cloud the truth with confusion and many an imposter counters truth on many levels; even reputable makers toss out statements. One famed sawmaker in Sheffield once told me that the Philadelphia Disston saws were made in Sheffield. In a culture of increasing falsity, we face the output of opinions that are nothing more than that. Opinions tell us that pull-strokes are better than push-strokes, bevel-ups are better than bevel-downs and harder steels are better than marginally softer ones for longevity but then not for resharpening. Such opinions, mostly non-factual, usually cause many to never determine for themselves what they prefer even though they may never have given both the same fair period of trial over a number of weeks and months. When we have more open minds, consider all things as possible, practical and practicable, we find that creative people in both realms can make most tools work and get used to them anyway. They can ultimately be used to give exemplary levels of workmanship and we should all remember that the finest work in the history of world woodworking was achieved centuries and even millennia before our present age except in the most exceptional of individuals. Thirty years ago, a Spear & Jackson catalogue advertised two classes of saw with descriptions I had never seen before. One description said, “Lasts five times longer than conventional saws.” This was in reference to their plastic-handled impulse-hardened handsaws. The second description described a wooden-handled handsaw as, “Resharpenable.” a term never used before that date because everyone assumed the saw would need resharpening periodically as part of general saw maintenance. In the first description, it did not tell you that that saw could not be resharpened; that it was indeed a throwaway saw. Within a couple of years, the resharpenable saw was no longer sold and for a couple of decades, it was abandoned as a marketable product. I’m not sure what made the difference. I do think I had a major part to play in restoring the use of handsaws to woodworkers by filling in the knowledge gap, of sharpening, setting, profiling teeth to task and so on, yes, but also my advocacy for lifestyle woodworking and the restoration of hand tools and techniques to woodworkers on a worldwide scale. My advocacy for the way we work being more significant when skills are pursued as a way of life has become all the more important. I plan to spend my remaining years researching and teaching as much as I can, as well as videoing and writing more books, manuals and of course my articles too. I want to leave the legacy I began working on 30 years ago. I have an amazing group of people around me every day testing out theories, writing, drawing, photographing and collating all the information. We have a massive archive to back up what we do and to challenge our theories too. What cannot be challenged is the validity of physical work with your hands, mind and body. Without working with my hands and my hand tools I would be amongst the most depressed and the most redundant. My output reaches hundreds of thousands of creative minds and keeps expanding when 30 years ago hand tool woodworking was all but gone. Imagine!

The Narrowing Down of Plane Throats

Some introductions are necessarily longer and I make no apologies for this one being so. The following article is also partially covered in my book Essential Woodworking Hand Tools, but my research, use of and concern for the all-metal, metal-cast planes have taken me deeper. Having spoken of it and demonstrated it for many years, some things are worth saying and even saying twice and thrice. Perhaps planes with narrowable throat openings have improved our lot. I doubt it for the main part and so `i find it more questionable than practical. Other gurus through the years have given the impression that we professionals are always adjusting the throat openings of our bench planes. We’re not, we never were and most likely we never will be. Looking at it practically from my personal long-time exposure in different woodworking trades and then through my own research into past centuries, nothing has changed except the sources of information. Adjustable throat opening adjustability seems to be more unneeded than advocated, for the main part. Its benefit option really affects our plane work in the most minimal of ways and yet so many these days espouse the benefit as more essential to good plane work (especially from tool salespeople looking for extra spin to confuse with). Vintage wooden planes used in bygone eras throughout a variety of woodworking crafts had no such option. I suggest that one in a thousand or ten thousand of crafting artisans might well have owned a plane with a special setting of a narrowed-down throat opening but in the day-to-day, it was more practical and useful to have 2-3mm openings. In other words, not closed down at all, ever. Take any new old stock wooden plane and the throat opening will be at its narrowest. Gradually, through use and an occasional truing of the plane sole itself, etc the opening naturally gets larger year on year. In many cases, the throat is narrowed down again by adding a wooden insert to the sole in front of the mouth opening. In practical ways, the throat opening on most planes can remain the same for decades and your work will always come good.

As it has become with all things woodworking, what was always really quite simple has now become more confusingly complex by information overload. Why do I say that? Mostly it has become so because trades handed down from crafting artisan to apprentice no longer exists and ceased decades ago. Standing at the bench, sharpening a saw or a chisel, setting up a plane or learning to saw straight was monitored by an experienced man or indeed many men. That mentoring capacity preserved the art of many crafts for millennia. It has never been replaced. Now we face opposition from many opinions that serve mostly to confuse. Sharpening does not need micro-bevels and bevel-up planes can cause many, many more issues than they resolve there at the workbench. It’s possibly nice to own an alternative type, but far from essential. These are simple facts you get to know through experience and not merely an opinion of picking up a plane and using it for a short time. I’ve said it before and I will say it now, the tool you end up preferring will be the one you pick out and pick up the most when you need it. That said, there is nothing wrong with owning a nice this or an adjustable that.

Do We Need an Adjustable Plane Throat?

Basically, this question only came into being when the option was offered with the introduction of the Bailey-pattern bench planes in the latter part of the 1860s. But the question has come up again in more recent history with the reintroduction of the once generally rejected Bedrock version of Stanley planes. Before then, in metal and wood versions, all planes had fixed throat openings and any that were indeed changeable were rarely changed if ever anyway. Stanley Rule & Level ended up owning and manufacturing the Leonard Bailey-pattern bench plane types and subsequent to that the Stanley BedRock-pattern bench planes, which have gained modest popularity and favour over the last three decades but not because of the adjustability of the throat but for the quality of engineering standards. Both plane types have been produced as knock-offs of the Stanley makes by entities such as Clifton, Quang Sheng, Juumma, Lie Nielsen and Woodriver, all of which acknowledge these planes as original Stanley BedRock designs somewhere in their information. Makers in the USA, Mexico, Asia, England and Germany have all had production facilities copying both Stanley versions of the plane under various names when Stanley’s patents ran out. No maker in any of those countries came up with anything new and significant much beyond a changed alloy. But all of them did offer tighter engineering tolerances and thicker, heavier metals resulting in heavier planes. I say this solely to say that that is just how good the Leonard Bailey designs were in giving us one of the most formidable hand plane designs in the Bailey-pattern planes ever invented.

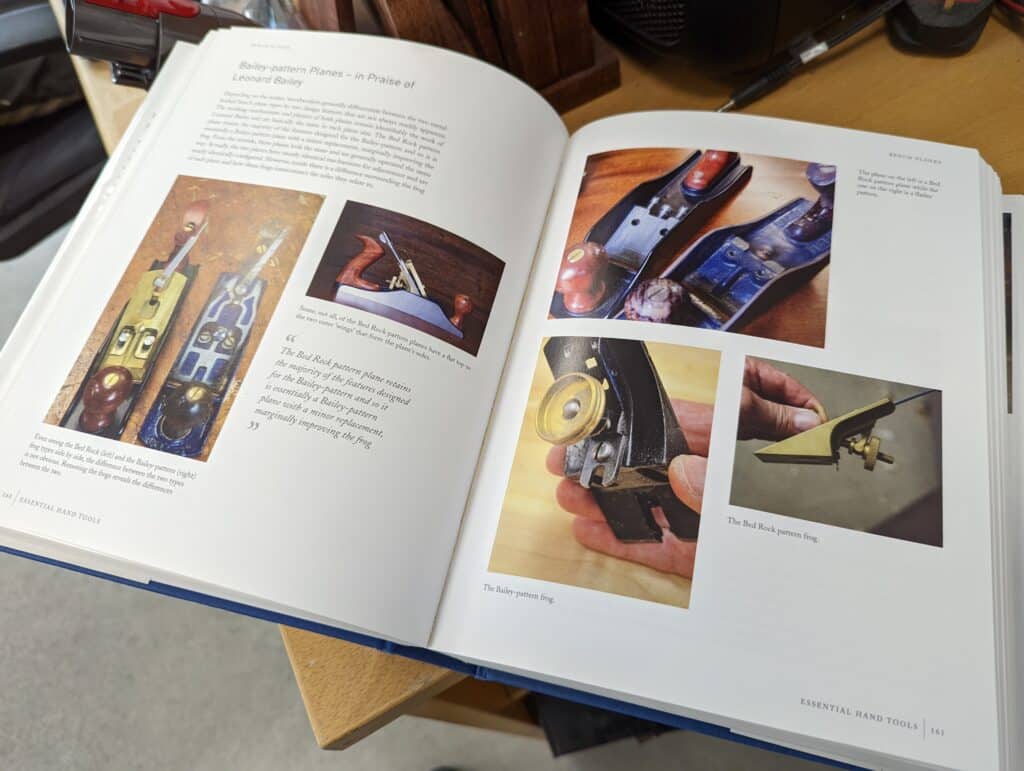

The difference between the Leonard Bailey-pattern plane and the BedRock version lies only in the way the frog is designed, installed and retained. The frog in these two plane types is an angled block of metal designed to elevate the cutting iron to an angle (the bed angle) of around 45º and which is anchored by twin setscrews to the main body and sole of the plane sole. That said, the two plane types have two different systems of anchorage. The BedRock version is cleverly devised to remove any possibility of slippage, hence the name BedRock. By installing three setscrews, counterpoised two against one, the frog sits immovably in the sole permanently. The Bailey pattern frog is also anchored to the sole with two setscrews through the frog directly to the sole. This too works perfectly well, is simpler and, in general, never moves. Some makers have attempted to cast the sole with a built-in or cast-in incline as a single-piece casting. I never queried why it didn’t work well and seems always to have been abandoned, but perhaps the combination of metal mass in one concentrated centre reacted negatively with any thinner areas around it and resulted in periodic distortion through different exchanges of temperature. No matter. It still seems remarkable that the plane adjustment mechanisms, the sizing of components, and other detailing, have all remained exactly the same for around a hundred years. Looking at the BedRock, we again see that the minimal difference to the overall Bailey-pattern remains testament to the quality of Leonard-Bailey’s investment of energy to invent a totally adjustable plane by the tweaking of a lever and the turning of a rotary wheel singlehandedly with the dominant hand. Norris and several British makers came up with a threaded-rod adjuster that could also lever left and right to align the cutting iron to the sole and then turn for depth adjustment too. This was copied by the Lee Valley Veritas range of planes. Compared to the Bailey model, it was slow, needed two hands, and was less precise than Bailey’s system in the bench plane range of bevel-down planes and in my view never an equal to Leonard Bailey’s endeavour for quick efficiency.

The Main Differences Between the Two Frogs.

If you are a seasoned hand tool user or enthusiast, you will already know that the key differences between these two frogs are in the shape and types of frog. We tend to think that this alone is the difference, but there is more to it than that. It’s as much to do with how the frog sits, adds to or reduces weight to the plane, the clunkiness weight often gives and how it feels in the hand, in the work and in the working of it. I have worked substantially with all plane types through almost six decades including every BedRock the makers of which always introduce it as a superior product for a range of exclusive reasons. My quest now is to give my point of view so that people can rethink if they indeed think that planes thus made will make them the better woodworker or that accepting the plainest of Stanley’s the lesser man- and woman-maker. I can make any Stanley create as well as the highest of high-end maker planes and give me even more; it’s my belief that you can too. I pass on any working knowledge I have from using them for half a century most days. It’s not an advocacy for nostalgia in any way. The pure reality of using them make things crystal clear and you too will be able to create wonderful work with any £15-30 plane for the rest of your working life.

On To the Frog in Your Throat

These points of contact can vary in precision and quality but generally, I have found them to be good and in need of no refining. That said, they can be readily refined if needed. If, however, there is any variance in these levels, tightening them down is not the answer as this can flex the sole into a twist which therefore will twist the outcome of your plane work. It is not likely that this will happen. I only saw it once in hundreds of planes. A quick file with a mill file, abrasive or diamond hone readily takes one or the other down, and any rocking will be easily detected.

What modern-day exponents for the BedRocks inevitably do, disingenuously in my view, and to sell something in most cases, is tell you first of all that it is regularly necessary to alter the throat opening to deal with plane chatter and difficult grain and how easy it is to adjust that throat opening of the BedRocks over the Bailey-pattern version. This is something most woodworkers rarely if ever challenge because, well, they simply don’t know. What you do need to know is that in 99.9% of all woodworking tasks with plane work need the throat opening to be wide open, somewhere between 2-3mm. At this more open setting, nothing will generally go wrong. At this opening, shavings are regularly emitted from the plane stroke on stroke, day in and day out and throughout the life of the plane. I have used the same Bailey-pattern plane for 58 years to date. It’s been at the same setting for almost 58 years to date. I have only closed it tighter half a dozen times if that and I could have managed perfectly well without it. It’s been the same throughout the ages for 150 years of Stanley planes and it’s no different for any maker that copied the Stanely planes when Stanley stopped making, whether that be the Bailey-pattern or the BedRock pattern. The most critically important thing to understand though is not the ease of changing the BedRock over the Bailey but that which they never tell you — when you do change the throat opening of any BedRock plane, no matter the maker, you always automatically and unintentionally reset the plane’s cutting depth to a deeper-cut setting when you close down the throat even by any amount whatsoever. On some, if not all work, this will be devastating if you forget to also readjust the depth of cut to compensate for the downward slide of the BedRock frog. Why is it that no one making or selling BedRock planes ever mentions this up front? Why do you think?

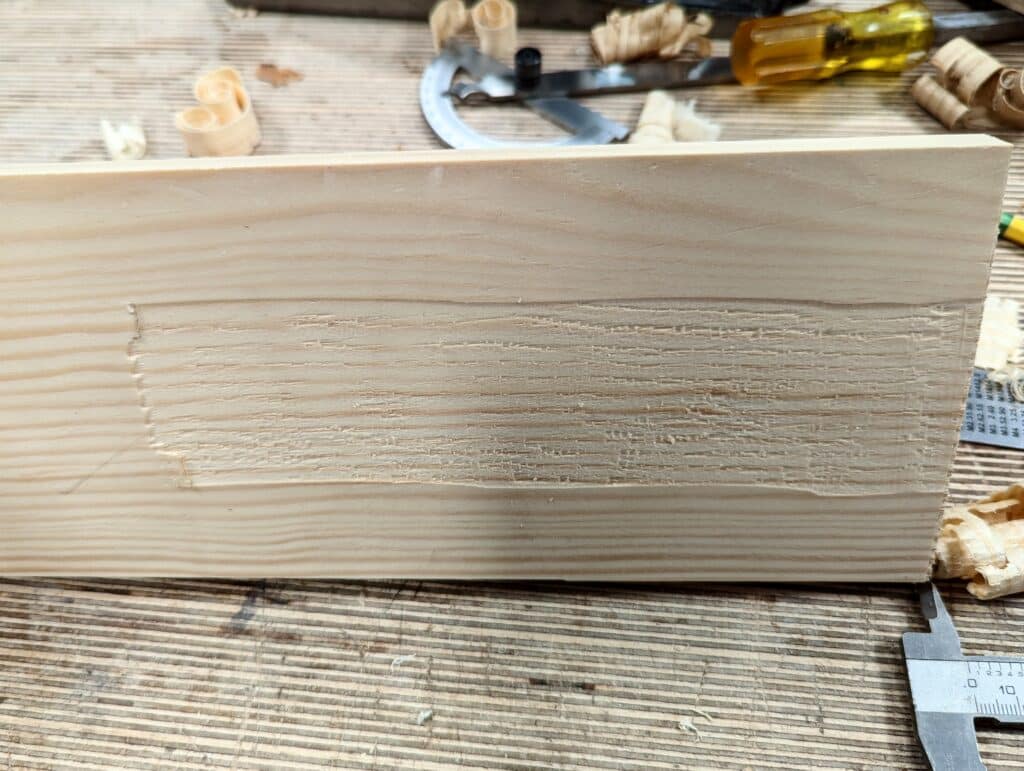

In my tests on the BedRock high-end planes, the shavings went from a near and, for me, immeasurable thinness to an impossible stroke because of the vastly increased depth of cut resulting in excessively thick shavings. This is without changing the setting of the depth via the usual way using the adjustment wheel. We should perhaps talk about this first. I initially recognised this at a US travelling woodworking show where a demonstrator showcased the ease with which he changed the setting of the throat opening to an audience of a half a dozen men. This feature seemed to fascinate the cluster of people surrounding the planing demonstrator yet he never told the audience that you rarely and in many cases never actually use the feature at all. They smiled and marvelled at the efficiency and the engineering, the weight of the plane and its fine feel and combined with an explanation of how this had improved over “ordinary planes such as the Bailey-planes” I became more interested. Just what was this about it being easy to change the throat opening?

All through my career of woodworking, the men I worked under and with never relieved the setscrews holding the frog to the sole in Bailey-pattern planes. They simply turned the adjustment setscrew beneath the depth adjustment wheel, placed their planes to the wood and continued working with them. That didn’t happen with the demonstrator there in the US show. Why? Asking myself this question I remembered that BedRock planes were the rarity and scarcity and no one I ever knew in Britain owned anything but the Baileys. I picked up the demonstrator’s plane and felt for the cutting edge. There was my answer. The blade protrusion was suddenly way, way too deep to function. I moved along knowing then that the plane was indeed automatically reset to a new and significant depth simply by closing down the throat a little; I felt this to be a fairly useless improvement and understood why the plane was so rejected by working craftsmen. The feature espoused as advantageous actually resulted in a disadvantage. This for me was a major issue of counterproductiveness. Any advantage was suddenly negated even though the advantage was indeed questionable. The quick change of the unneeded throat change resulted in a slow set of the plane’s depth of cut and thereby the immediacy of functionality.

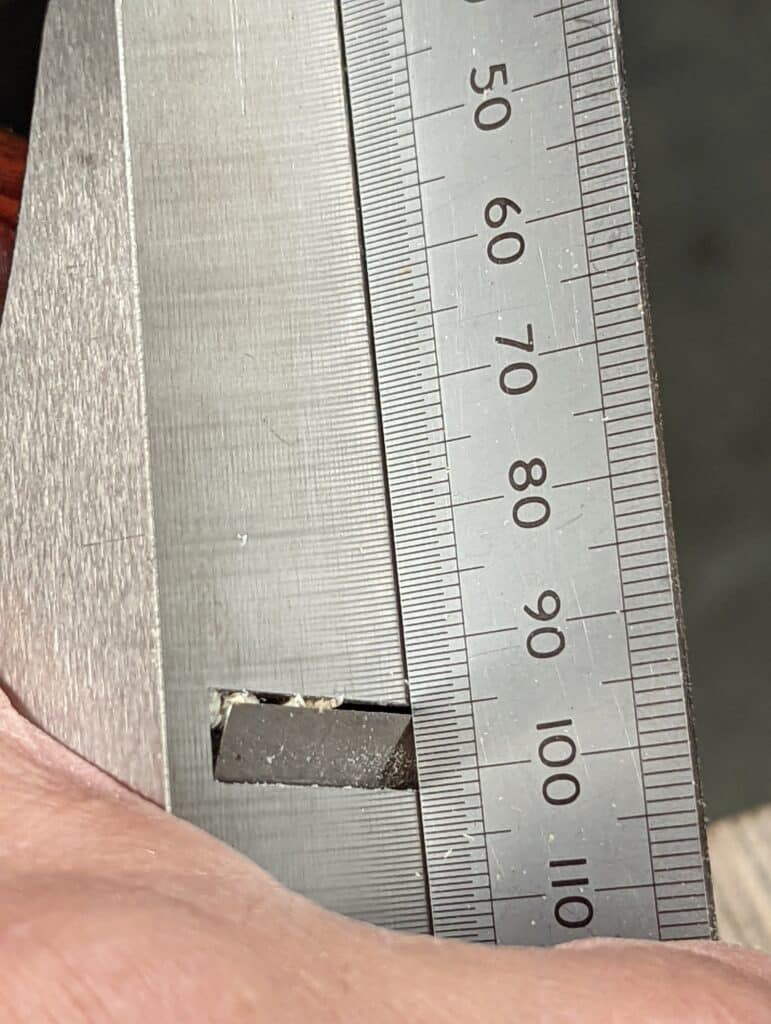

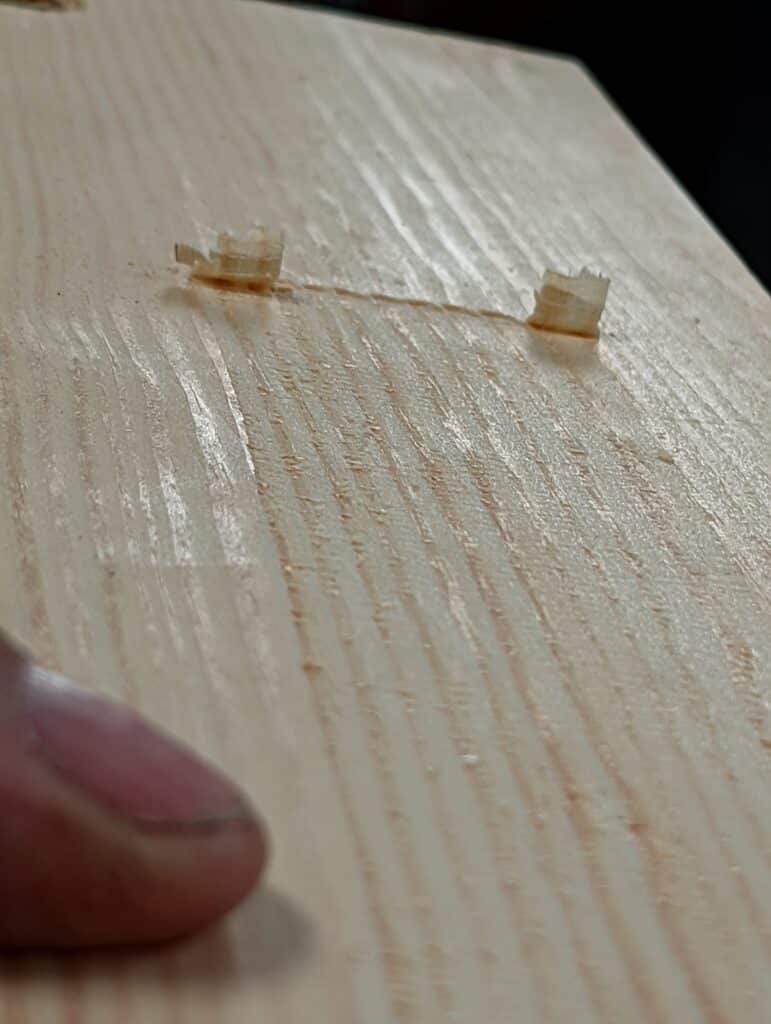

Turning the centre setscrew that shunts the frog up or down its inclined platform on the insides of the soles of any and all BedRock planes one full revolution from the zero point, the point of taking the most minutely thin shaving off the wood, closes down the mouth opening from about 2mm to somewhere close to give or take 1mm. It’s a small but necessary gap, not much of an opening at all, but one you might go to to tackle something really wild and difficult on a special hardwood you needed for something you are making. But here is the real issue. The depth of cut achieved by any turn large or small to close down the throat some also markedly alters the depth of cut and takes the blade down through the throat of the sole by about as deep as you can set the plane depth to using the wheel depth adjuster. In other words, the cutter will not take a shaving so much as gouge deeply into the wood and most likely scar it irreparably as shown above. The chief and significant point in this is that this change always happens and cannot not happen. On standard Leonard Bailey pattern planes, on the other hand, this never happens with changing the position of the frog on the much-dissed Bailey-pattern plane because it cannot happen. Why? The frog is set paraplanar to the face of the sole on two levels but without any incline so moving the frog backwards and forward is a parallel motion along fixed-height points.

On BedRock Planes

Taking the plane with its frog shunted forward to close down the throat from zero-thickness shaving both narrows down the throat opening but at the same time, in tandem and unintentionally, automatically changes the depth of cut to a massive .62mm — so thick the shaving is not a shaving but a staggered fractured coil that then leaves a skudded surface like you have never seen before. This means the supposed benefit the BedRock plane pattern might possibly offer is sorely negated by having to majorly adjust the depth of cut to a safe level. Even in experienced hands, this is no minor inconvenience to anyone planing wood.

Conclusion:

This has been an interesting consideration. I think covering off the major concern has identified several different issues. The major danger here might be throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Why would you? Identifying the fact that you do automatically misset the depth of cut of your plane iron will also ensure that if you adjust the depth of cut back to zero via the depth-adjustment wheel you eliminate or at least minimise the risk of damaging your work. If indeed you become practised in automatically considering the depth of set after closing the throat down before you apply the plane to the wood you should have no problems. You already own a good plane. If you listen to what I say about the unlikelihood of needing to change the throat opening then your plane will always be ready for action. Just use it. If on the other hand, you are perpetually working with wiry- and awkward-grained woods then you will get used to resetting the depth of cut. It’s just important to know that BedRock planes come with a built-in problem and that they did not nor do they resolve any real-life issues.

The Bailey pattern frog, even when cinched tight, can still be moved forwards or backwards with the whole assembly in place, clamped down and solid on every `bailey pattern plane I have used. But cinching the two setscrews tight and then backing the screws just the smallest fraction of a turn will not render the holding capacity of the frog to the sole by any noticeable and negative amount. The frog will always hold its place just fine. The main advantage in this is that you can readily move the frog back and forth with a simple turn of the setscrew at the back of and lower part of the frog. Doing this in no way changes the depth of cut. Simply put, alter the throat opening by any amount you like, apply the plane to the wood and the depth setting remains just as it was before the change of throat opening size. You just might never need to ever change the tightness of the two setscrews for the rest of your working life. Just like me!

I’ve heard some pretty prominent ‘woodworking personalities’ say that ‘you should not waste your time and money on a vintage Bailey-pattern plane and ‘spend the money once and buy a modern Woodriver plane with a thick iron’. According to these people, if I were to try a vintage plane, I would be doomed to a life of frustration with the inferior equipment and constant plane chatter.

Luckily for me, I ‘found’ those personalities AFTER I had already learned my techniques from your videos, Paul. I had also built quite a few items by this point and I was puzzled.

Puzzled by the fact that I had (apparently) made the mistake of buying vintage Stanley planes and used them without any frustration in setup or noticing any chatter. In fact, I started looking for chatter. Why wasn’t I experiencing this plague that could only be solved with a thick blade and high-value modern tools?

Turns out that learning from your videos, Paul, had armed me with techniques on using and sharpening my tools. That, in turn, allowed me to never experience any these issues. When I do encounter something strange, I usually know how to fix it, because (as you mention in an earlier post) I have taken apart every plane that’s come into my hands and learned how to optimize it and put it back together. I have now restored several planes for friends, and I have yet to have one of them come back to me and say it didn’t work well.

Thanks for giving us the benefit of your experience. Without your videos and posts, I would likely not have enjoyed woodworking over the last few years like I have.

I went off on a tangent in the above post (sorry about that).

What I wanted to say is: Because of the online hype about the Bedrock clones, I bought a Woodriver #4. It was nice. It still needed initial setup, just like a vintage Stanley. It planed the same as my $5 Stanley, and it was heavier, so I got rid of it. Luckily, I was able to make my money back.

The thicker casting was a noticeable annoyance. The frog was no more stable than my Stanley #4 and I never adjusted the mouth after the initial setup (so I did not encounter either the advantages or drawbacks of the Bedrock design).

I doubt anyone who does hand tool woodworking spends much time adjusting the mouth of the plane back and forth. I have a low-angle jack with an adjustable mouth and even with that simple mechanism, I can only remember one occasion when I wanted to close the mouth down (on some wild grain wood) and even then it was only to try it, and I don’t think it was that helpful.

Personally, I prefer wooden planes, but that’s another story. 🙂

I’m terribly interested in who those personalities were.

All the hand-tool focused YouTubers I’ve been watching are pretty gung ho about classic Bailey planes (Rex Kreuger, Matt Estlea, Will Wright, and of course Paul here.)

They seem to really love a good Veritas or Lee Nielson as well, but haven’t had anything bad to say about the classic Stanleys.

Hey Eric,

I am reluctant to come out and name them for two reasons:

1) After reading my first post, I realized it was not very polite. I couldn’t delete it by that point. My mistake.

Since I had spent the money on one of those planes after their recommendations and was disappointed by my overall experience (not worth the money, basically), I guess I still am nursing a bit of a grudge. 🙁

2) They’re otherwise very useful channels. I like their work, and have learned from their videos. I just don’t pay any attention to any their reviews anymore. That’s not just based on their plane reviews, but other things as well.

Basically, if you see a woodworking channel where they have sponsors, or worse – where they are vendors themselves, then I’d suggest being a little wary of their reviews as they are necessarily biased. Rex and James Wright are great guys with unfettered channels, so I also pay attention to them. As Paul points out, he doesn’t have sponsors so he doesn’t feel the need to recommend their stuff.

Fair enough.

I definitely pay attention to whether or not the channel is being sponsored. I do appreciate when I know there’s no money changing hands with the manufacturer of whatever’s being recommended.

Try Garrett Hack for instance. He has a book out for years now called “The Handplane Book” he’s a Big proponent of bedrock planes, thick irons, Lie Nielsen, and expensive sharpening stones. He’s been a contributing editor for fine woodworking for years. Before I had ever heard of Paul I had read his stuff and watched his videos. Nowhere near to being helpful like Paul’s instruction. That’s just my opinion though.

After reading most of this article I can agree with it in its entirety: This man is obviously time served and like myself has had a thorough grounding as an apprentice I too am an avid tool collector and plane freak it makes a pleasant change to read sensible comments made by someone who has the knowledge and is not afraid to say so

Thanks for the detailed blog Paul.

I have been using ‘classic’ Stanley Bailey planes (and a few Records) for my projects for a few years now – the ‘usual suspects’, i.e. Stanley Baily #4, 4.5 and 6. All bought second hand and ‘tuned’ up to work optimal again.

One day I saw a #4 Bedrock plane being sold in my country of residence for a reasonable price. Since I also read the internet hype on these planes and how they are supposedly better than the ‘normal’ Stanley baily planes, I decided to buy it.

After restoring/tuning it, I tried it for a while for a few projects. Long story short, at the end of the day I sold it off and went back to my normal #4.

Main reason was the weight difference – every time after I used the bedrock and switched back to the baily, it just felt so light and ease of doing the work (especially if one had to prepare a lot of planks).

I also couldn’t really see/observe a difference in the work being done by the two planes – both did the job at the end of the day, but the lighter plane won out for me.

That’s good to hear since I’m “too broke for Bedrocks.” Sounds like a title for a depressing country song, huh? 🙄

I enjoy restoring tools much more than the actual woodwork and what wows me is finding derelicts cheap so I can do the restore. Like a #4 type 13 for $8.00 in beat shape but I saved her life… got good at it! That said, all of my users are Baileys and they just… work. Goal is to make everything in the hangar prewar, patina required. 😁

The only exotic thing where resistance is futile are Sargent autosets, I love the rakish looks.

Wooden planes, I’d ratchet jaw all day on those, I love mine to death!

Interesting. The only Stanley Bailey’s I have are a No. 6 Foreplane made in England and bought new in the mid ’90’s along with a Record No. 4, and a No. 5 Jack plane bought within the last year that was made in Mexico. What a difference in the casting and finish. I happened to pick up a Sargent No. 409 from a couple of trucker friends in need of beer money ($10.00) in the mid ’90’s as well and am just now getting around to “Fettling” it, as Mr. Sellers would say. I must ask, what is a Sargent “Autoset” and how are they different?

I have fallen for many of the supposed advantages of new tools.

This includes power tools, there was a time for instance where every woodworker started to use biscuit joiners. It was a fad in the 1980s and I bought one. I used it a couple of times and then tried to give it away because the tool had a way of moving and making sloppy joints. I finally threw it out when I couldn’t even give it away. I fell for the thicker hard plane blades only to find I was spending a lot more time sharpening and trying to break the wire edge negating the 10 or so strokes it might have stayed sharper. Now there are very expensive fastening “systems” and I have finally learned my lesson and will never buy them. Sometimes you have to learn the hard way I think. I wish I had practical advice when starting out, thanks for the explanations Paul.

Thicker plane irons were going to shut the chatter down. So too were the Bedrock planes because the blade was totally supported from behind when you narrowed the throat opening, which apparently those proponents of such were doing multiple times a day even though we have a lifelong woodworker writing and telling us you don’t do that. Marketing.

Once again, Paul, you’ve hit the nail squarely upon its head! I was one of those you’ve described, readily buying the sales pitch, too inexperienced to know the difference…though my experience has taught the same lesson it taught you. My Bailey #4 leaves the same, finish-ready surface my Lie-Nielsen #4 ½ delivers…$40 vs $350. I will not deny the joy/satisfaction yielded by the Lie-Nielsen, but the “necessity” of the higher priced tool is clearly challenged.

Thanks again, Paul, for bringing truth to the fore.

Doesn’t this apply mostly to bevel-down planes? I have some Lee Valley bevel-up planes where the adjustment of the throat is done by moving the front of the sole. While I am not experienced enough to have an opinion on how frequent the need of adjustment might be, I can’t see that the depth of cut is affected by this technical solution.

The planes you mention, also like block planes with a movable sole, do not affect the depth of cut because they move an adjustable portion of the sole, not the cutting iron/blade assembly. On the Bailey Pattern hand planes, the frog, while holding the entire cutting iron/blade assembly may be moved back and forth to open or close the gap between the blade’s edge and the front of the mouth opening. It does so while traveling on four flat, level “pads”, or “bosses” without changing elevation – so nothing goes up or down. On Bedrock Pattern planes, the frog is adjusted the came way, but the frog is mated to the plane body on an inclined plane, which raises the cutting iron assembly when moved back to open the gap and, conversely, moves the entire assembly down when moved forward to close the gap between the mouth of the plane and the cutting edge of the cutting iron/blade.

One of the very best articles you have written Paul.

What you have again shown is that any claimed benefit of change, in any tool is the “Sprat to catch a Mackerel” i.e the buyer.

Thank you for your clear demonstration of your viewpoint ! Excellent.

Hi Paul I saw a discussion between you and a reader on the post “garage upgrade and more” where the subject of quality was addressed. Would you say you seek perfection in your work? Or consider yourself a perfectionist? When you worked on projects such as the collection for the white house was it or had it got to be perfect?. Or would you say you work to the best of your ability and expect that their will be minor imperfections in your work and you have to just accept it?.

Wife gave me a Veritas plane for Christmas a few years back. It has adjustable opening. Easy to adjust. Blade depth does not change when opening or narrowing. A bit heavy and expensive but also an excellent plane. It is my go to plane when worried about tear out.

Whereas Veritas and other bevel-up planes work nicely you may well have just been favoured not to meet adverse grain with it. When a bevel-up plane tears it tears magnificently. Be ready!

True. Not just little chunks but whole bands of adverse grain! If you like massive tear out ‘bevel up’ is what you need. I like mine on the shooting board for end grain and joining soundboards and backs (the Dictum planes are really perfect for that, with their higher sides, and recessed cap iron, which gives you a plave for your fingers… ) but it certainly is NOT the first plane to buy.

It doesn’t replace a regular 5 (or 4) as most advocates of the ’62’ hype try to tell you. I like the feel of the ‘low angle’ plane, but it’s not as versatile as they say. And if you sharpen your blades with a secondary bevel it no longer is a ‘low angle plane’.

Hi Paul, Really appreciate the articles. The Veritas I have is a bevel down, #4 Smooth Plane. It is definitely the one I use for difficult grain. I keep it at a relatively narrow opening. My other Bailey planes #4 & #5 (various mfgs) are used more frequently and when grain pattern is not a big concern.

Paul. Accepting for the moment that there are occasions, with certain types of grain, when a very narrow mouth is desirable, why have none of the manufacturers produced a bench plane where the front part of the sole slides backwards and forwards, as is common with block planes? This adjusts the mouth without moving the frog.

Veritas have done an excellent job on this in several of their planes.

I got an ece wooden plane used with a moveable mouth. I really like it but it needs some work. Wooden planes are the bee’s knees.

One advantage of the big hulky planes and tools is you get biceps like Hulk Hogan!

Possibly difficult, expensive, to manufacture to provide a quality product. I often wonder why they haven’t made ones with replaceable blades to enhance our throwaway society. I do seem to remember that the Stanley SB10 did have them. Perhaps, like me, no one really wants this feature. Although I have bought second hand planes that appear to have had no / very little sharpening.

Ivor, the Veritas bench plane I have does this. The whole frog slides. Try to find a youtube on how it works. I like mine, it works very well and rock solid. However, like Paul has noted, most of the time adjusting the opening is not needed.

Hello Paul `Relatively new to the guild, except my grandfather tried 50 years ago to install his knowledge and “love” for a his trait, I now start slowly to get into wood working with hand tools. (wood always fascinated me but sadly was blinded by the instant “satisfaction” of power tools.

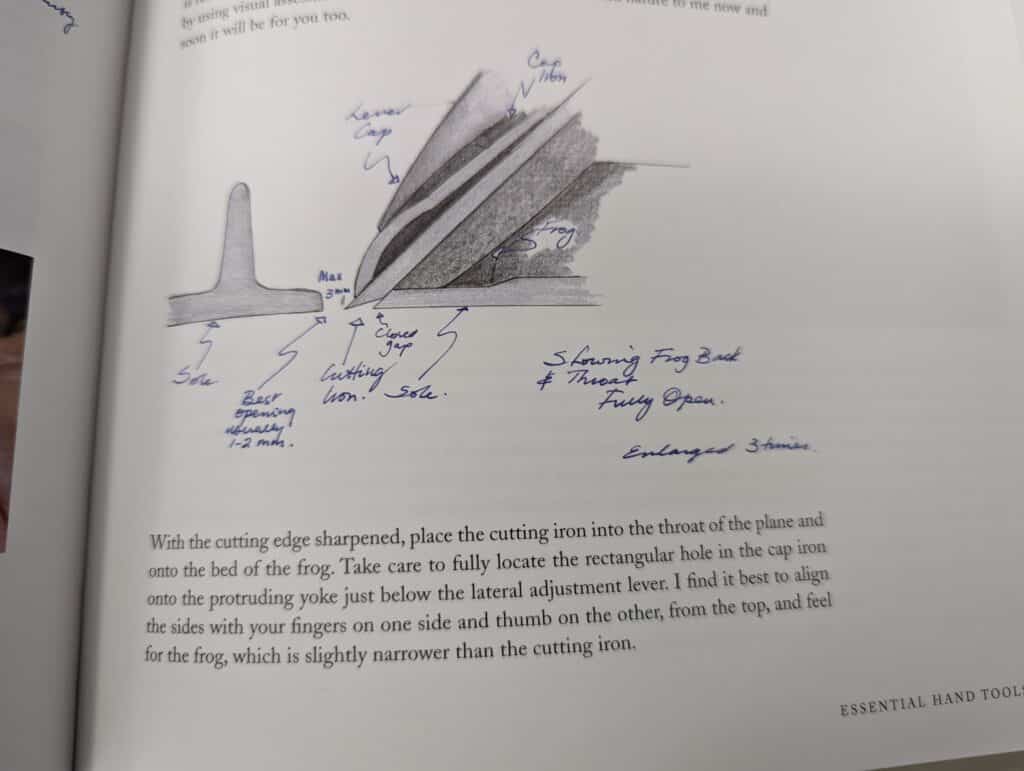

I think I can remember that I read in one of the articles the mouth should always be as close as possible. You mentioned it should be 1-2mm, in your drawing you say “max3mm”

Could you please elaborate WHY the throat opening has such an effect on the outcome of the surface.

If you have explained this already, my apology for not having discovered it, and please could you point me in the right direction.

With deepest gratitude and a huge thank you

Guido

Guido,

It has to do with how the plane cuts. If you’re going with the grain at all times, the mouth of the plane can be pretty wide before you notice anything amiss.

If you have rising grain, or varied grain, the plane iron tends to lift the wood a bit and it will start to split along the grain ahead of the iron. The sole at the front of the plane presses down on the wood ahead of the iron and holds the splitting back. If the mouth is set very fine, then the wood is held down until almost the moment when the iron will cut it, making for a nicer surface.

The mouth adjustment may help but in most cases, if the wood has really wild grain, you’re going to have to resort to a higher-angle plane or a card scraper. Even with the mouth closed up a lot, the surface will still need refinement.

Generally, if you’re planing with the grain with a fine cut and a sharp iron, the mouth gap is not as important.

Hello Johann

Thank you so much for your explanation. Yes it makes total sense now.

I bought a 604 recently at a antique store. The plane iron says Bedrock but it has the Bailey type frog. I’m a bit confused as I’ve seen it written that the Bedrock uses a three screws to the rear on the frog, whilst a Bailey has only one to the rear and the hold down screws are vertical.

Do I have a FrankenPlane???

You can tell from the pictures in this blog post if it’s a brick or a Bailey. Just check out the frog. The irons could be interchangeable.

If your Bedrock has round sides it will only have one screw in the back. The frog attaches in the same direction as a Bailey.

Flat top Bedrocks have the special pins and the tensioning screws are accessed from the back.

If you remove the frog it should have a single mounting surface on the bottom and look like a wedge from the side.

Sometimes you will find planes put together with various parts not original to the plane. Recently at an antique barn I found 2 planes of interest. I was just about to pull the trigger until I disassembled and found the frogs to be a replacement that didn’t quite line up to the opening.

Hi Paul. I have a Stanley 4 and antique wooden block planes. They give good results generally but often I struggle with on cheap wood that varies wildly in hardness and grain direction. No doubt this is largely a lack of skill in sharpening and use. At this point I reach for an electric plane. Miraculously they produce a very good finish with no skill at all. The thickness planer especially. One significant point of difference is that hand planes have flat beds and protruding blades whereas electric planes, jointers and thicknessers have the blade level with the rear sole and a front sole raised by the depth of cut. Has a hand plane ever been devised on this pattern? It seems a better approach.

Not as far as I know and that’s because we don’t need it for our type of woodworking. There is no real comparison between an electric planer and a hand plane. Two different animals really. The main difference is machines take off thousands of chips per inch and the hand plane a single 10″ or so long shaving per 1″ or so width. I doubt anyone would expect good results from the kind of wood you describe. A hand plane will not do well regardless of skill levels or plane type, so it’s not you but the nature of the wood standard and hand planing. That said, it was you that chose to plane the impossible so it your were the one responsible in the end. Yes, we pick out our wood, choose plane direction, plane type type and technique to get the glass smooth finish we strive for with hand tools. Most of those of us who have chosen the path of hand tools did it consciously and willingly to avoid machine methods and for good reasons so we use hand planes with no regrets. Having worked with machines throughout much of my 57 years of daily woodworking full time, I made decision so it isn’t that I just missed something and didn’t know any better. I chose it because it gives me the greatest level of fulfilment not turning to power equipment to true up and make my wood ready. I wouldn’t really describe using a machine to be some “miraculous” event, Ian, perhaps developing hand skills is more along that line. I mean, when you see your wood being transformed by the skills you’e developed, the whole game changes.

[quote]electric planes, jointers and thicknessers have the blade level with the rear sole and a front sole raised by the depth of cut. Has a hand plane ever been devised on this pattern? [/quote]

Yes. Several, e.g. Hardt’s patent in the late 1800’s.

Nice looking planes, too, with the toe on a wedge bed just like a machine jointer. The idea seems to have been an unnecessary complication, though. (No clear advantage). Something nags at my mind regarding a shoulder plane, but it could just be a past memory of something to try, should opportunity present. (not a factual memory of an existing example)

Radically different planing strategies for shoulder/rebate/rabbet planes. Face planing allows the plane to move in just about any direction, from left to right on extremely wide surfaces,etc. Shoulder/rabate/rabbet planing is always inline, parallel to an adjacent face, extremely controlled and of course measured as in controlled as much as you want it to be.

[quote] shoulder/rebate/rabbet planes….[/quote]

Thanks, that jogged my memory.

it was a Stanley #11 bullnose rabbet. The frame swings. There were others sliding or swinging, but point taken.

The Hardt patent, however, was applied to cast iron jointers, smoothing planes….and a block plane. Ironically the patent considered wooden body. All the (few) extant versions are cast iron & nicely built. However, they clearly never found a market.

Hi Paul, what is the point of an adjustable throat on a hand plane and what exactly does it achieve if adjusted wide or narrow. Hope this isn’t a stupid question of I’ve misinterpreted some thing.

It’s a great question, Paul. Just excellent. Why? After 58 years using a plane with a moveable frog to adjust the throat opening I might possibly have used it half a dozen times three of which made no difference to the result at all. Basically this extravagant addition offers only two options. One we keep at its wide opening at about 2.5mm and then the other down to usually about .5mm or possibly a bit wider at 1mm depending on almost nothing except the thickness of the shaving you might want to take which is usually the thinnest if you are worried about grain tear. To be honest, I might suggest 98% of serious woodworkers never use the feature and new woodworkers fiddle with it because, well, the plane’s not doing well and anything might help make things better, in which case it won’t. If I did have a situation needing extra care because of some grain that I know before hand would not plane I would just not waste my time. I would pull out the #80 cabinet scraper and deal with the problem area with that or a card scraper. I might even reach for a belt sander if it was really needed but do not usually. The theory behind narrowing the throat opening, and it does help if you don’t have access to any alternative, is that you tighten the distance between the back edge of the fore part of the plane sole and the cutting edge. Because the fore part of the plane is bearing down on the wood, the wood is prevented from lifting up before the cutter has the opportunity to engage the fibres and cut them. So having said all of that, I know some woodworkers using certain woods will benefit from a closed down throat and they keep a plane set tight for those woods. Think luthier, for instance, working figured Maple for the bouts of a cello or a violin, guitar front or back.

Feels like a lot of “get off my lawn” here.

I have had all types described above: Bailey, Bedrock, Lie Nielsen, Veritas. Bevel up and bevel down. They will all do the job. I will say that the newer, high quality planes really are a joy to work with compared to their ancestors. Take a great design and put very high end modern machining to it. It seems like a win – win, albeit with a price tag attached. Also, supporting US/Canadian businesses who are keeping handwork alive.

Also, most people who are using hand planes on a regular basis these days are hobbyists, and I don’t know about you, but I’d rather spend my time making things than restoring/fiddling with old planes. But as with all things, YMMV.

That’s just plane silly and perhaps a tad inconsiderate, but it’s also expected from one or two. There are, you are right, the “US/Canada businesses” to think of, but then there is the rest of this great big beautiful world filled with great, big, beautiful woodworkers on another four continents. I’m not sure why you left out the whole of Asia and the whole of Europe, the whole of South America and your southern neighbours who make the US Stanley planes these days. My article was of course not only for a few hundred thousand on one continent but the other 7 billion inhabitants of the planet. Of course, I was mainly addressing several more important issues really, not the least of which was to simply counter the disinformation re BedRock versus Bailey where people might be misled or even deceived into believing that BedRock planes gave better results when a Bailey. A Bailey, well proven by hundreds of thousand of more users than a BedRock, will always hit the spot and may even prove better and especially more affordable for the global world of woodworkers. You accusing others of being on their turf does not make it so but it is easy to throw out the odd straw man here and there and have people all the more confused rather than just present the truth for them to learn from. Most unhelpful, I’d say. You missed the whole point of the article in your quest to somehow declare such businesses as keeping handwork alive. That’s not the case at all. I would venture to say that thousands and thousands of eBay suppliers are the ones helping woodworkers to keep the craft alive because if the businesses you speak of stopped producing the craft would always continue simply because of who we the woodworkers are. Most woodworkers cannot spen hundreds of dollars on very expensive planes and other tools and I would not want anyone to think the Stanley to be in anyway only capable of lesser quality work when I can support them with the truth. Let me just say it here and now. Spend an hour on a sendhand Stanley one in a lifetime and you will have a plane for life that will never fail you. No need to reply to this James. Your contribution was unhelpful really, so I think we’re good now.

Dear Paul,

to my surprise my comment posted here is not available anymore. Was it deleted? And if so why?

Best,

Christian

I very occasionally take a comment down to consider its validity, give it some thought, see if it takes things off course, things like that. Sometimes I put them up again and sometimes not. I think mostly about the original intent of what I wrote, what it means to my audience and what I wanted to convey. If it goes off track I feel that that is the best thing to do.

I believe this gentleman would’ve described your reply in this manner: “Tact is the ability to tell someone to go to Hell in such a way that they look forward to the trip.” -Winston Churchill

Well said Paul !!!

Good afternoon Mr. Sellers.

My father was a great furniture maker, he was also mentor taught, and made many items for our family home. Unfortunately I never saw him do any of this as most items were made before I was born (mid war). no power tools available.

Fast forward to the 70,s. newly married(and skint!) I set to and built some wall cabinets and work tops, various bits and pieces for the house and garage, hand tools all; they were okay,ish!. Onto the second house and my expectations had risen so, using better wood and knowledge(I flatter myself!)I did the same again. Still no power tools. Now some moves later we arrive at our present abode, a skin-deep makeover of a welsh miners cottage, with, YES! a double garage in which I could practise my art. By this time I had amassed a small collection of wooden planes and Stanley/Bailey metal equivalents, I had also made a router table, table saw cabinet, with storage for my unused/unsharpened hand saws and two of three routers, powered saws Etc. Etc. All of these power tools made a hell of mess when used.

The wooden planes had all been machined on the sole, wide mouthed, with good old wrought iron blades but with no way of knowing if originally paired or a marriage. they work fine but will get better now that you have explained how the oldens would have dealt with this problem.

Mr. Sellers, is the reason that the blades on these planes are thicker at the sharp end is to impart resistance to the upward force generated when cutting the shaving, not to cure chatter?

My gathering of metal planes have all been sweetened, using your methods. The Stanley 4 1/5 was my go to but a Bailey No 36 has usurped it.

My journey into woodworking will continue, hopefully you teachings will overlap my need to know gaps, but for now I will keep them sharp, listen to the wood and enjoy the labour.

John Kenlock.

.

Can’t offer any insight myself, John, but I’m excited for you and your new start. I just struggle with planing full stop – my joints are getting better, even my dovetails, but I suppose I just need to keep getting the practice in on the planing. And it seems to be the basis of everything: if you haven’t trued up your stock properly nothing else works as it should.

[quote]is the reason that the blades on these planes are thicker at the sharp end is to impart resistance to the upward force generated when cutting the shaving, not to cure chatter?[/quote]

No. Primary reason – a wedge held iron will push up if it is not tapered thicker on the working end. Aggravating, if you’ve ever tried it.

secondary reason – most (all?) traditional tapered irons are laminated. Observe how much of the iron is left after the blade section is used up? No reason to add extra material then. There are also vibration issues, but i have not explored them.

Faint tertiary reason (speculative): running the steel back out on the iron backer uses less of it, eliminates a stress area; & is easier to forge weld with the thicker components in that area because they don’t chill as fast . The reason it is not then not forged out thinner? See primary reason.

Sorry, i just re-read your post,

Had initially misunderstood your force comment as relating to strenght (vs bending, perhaps)

You are of course right as in my response, the primary issue is preventing the entire iron from pushing up.

Apologies=

smt

i use stanley planes i have had for over 40 odd years. i have never opened or closed the throat on them. if i have difficult grain, i simply use it at an angle so as to slice the wood. money spent on expensive ego tools is money not put on the table for your family.

You don’t say how often or how long you physically used them for here. No one can really evaluate what you are saying.

Paul,

Sargent invented & patented the adjustable mouth before Stanley came up with

the Bedrock brand. In the Sargent design, the frog is parallel to the sole, whereas

the Bedrock is on an incline in order to get around the competitor’s patent.

Because of the Sargent design, the depth of cut doesn’t change when the mouth

does. One more example of something lost due to better marketing.

oh yes, the Sargent models can be found now & then, guess the owners tend to

keep them.

best regards.

Oh, dear. As I mentioned in a previous comment (to someone who touts Sargent “Autosets”), I have a Sargent No. 409. Now it looks like I may have to start looking for their models with adjustable mouths too? I suppose budgetary constraints will determine just how much of this rabbit will fit into that hole. 🙂

As novice planer and new owner of Luban Bedrock style plane purchased here in Oz some time ago, I passed a frustrating few weeks off and on, trying to re assemble my #4 once it required blade sharpening – not having discovered paulsellers.com.

Scant practical information for use or adjustment is offered by re sellers. Planers ipso facto, were all trained by our grandfathers. So next up was to wade through You Tube videos of Good ‘Ol Boys trucking their planes, not much use and mostly not meant to be. That’s why I spend well, next to no time on ‘socials’ or You Tube.

No explanations given of style differences such as Bailey v Bailey Bedrock or why to do this or that technique is sound, or should prevail. So, it was easy to apply totally incorrect solutions to my problem.

One day I decided to measure each component, check it for ‘truth’ and so on.

I had realized earlier chip breaker iron leading edge was machine bevelled at slight angle +/- 1mm across the edge – so what, that’s how it came, lets just keep it out of the way. Then I realized that trying to adjust it’s warp out of that narrow throat by shifting frog back had achieved what Paul describes in this post – changed the blade depth [in this case] to a position adjuster wheel could not deal with. McJing kindly supplied new chip breaker f.o.c. Some progress made at last, and now I stick with Paul’s versions of How To Do Stuff.

Why the post is missing since two weeks?

Hope Paul is well!

Until recently I owned 2 planes; a Wood River 5 1/2 and a 1937 Stanley #4 corrugated bottom. The #4 I got on ebay after watching one of Paul’s videos. I’ve recent acquired a smooth #4, a #3 to smooth small projects, a #5 Bedrock, a 607 bedrock ( as I only have a 4.5 in jointer that was my grandfather’s), and a #78 fillister/rabbet plane. It was a joy to tune each one and expand my ability to work on my projects. I’ve been woodworking for 59 years, starting when my grandfather brought me a tabletop jig saw, and I learn things from every video Paul puts out. Using the planes makes the craft more sensorial and gives me a greater connection to the wood. The one question I would ask Paul is about the claim of narrowing the throat reducing tear out in highly figured wood. Is that reasonable or do you do something else to plane those woods? Thank you.