A follow-up

The steeper the bevel is on a plane or chisel the more resilient the cutting edge will be but depending on how you use the blade will affect how it feels in the wood. Bevel down and with the blade elevated as in a bevel-down plane will make no difference. Bevel up, as in bevel-up planes, can make a marked difference depending on the steepness of the bevel at the cutting edge. Chisels are different. Chisels interplay throughout the day to be used bevel up and bevel down. Used with the bevel up is the paring cut used at the very lowest angle of presentation possible and an angle no plane can really work at. I doubt anyone would really notice much difference with steeper bevels on the chisel when used this way. An advantage of bevel-up planes is that it is easy to change the bevel by steepening the fore-edge with a micro-bevel topside; you might do this to plane potentially awkward grains such as figured or wavy-grained woods but, all too often, your bevel-up plane has already torn the grain irreconcilably by then so not always of benefit. Whether it is worth buying such a plane is a matter of pure choice. In other words, it depends on how often you need to change the dynamic because of the regularity you face in planing an area of wood that needs it. Personally, bevel-up planes work well on non-contradictory wood which is primarily end-grain planing only and that’s why they are popular. On most low-angle bevel-up planes it is mainly the added weight that helps bolster end-grain planing. End-grain planing is always approached with a predictability that face-grain planing does not have at all. Bolting your thick iron to a mass of weighty steel with no frog linkage and no cap iron solidifies the coupling. No gaps between the cutting iron right at the mouth of the plane, as there is at the bevel of the bevel-down plane, even though quite small, then eliminate that minute flex at this critical juncture and that’s why it feels and sounds different. Is it enough of a difference in planing the end grain of wood to justify spending £360 then? In my view no, not really. It’s purely a matter of choice and preference. You will get excellent results with a well-sharpened bevel-down plane. Makers, demonstrators and sellers of planes (ultimately salespeople anyway) and plane irons even suggest that there is a “trick” and that, ‘the trick is buying two or three extra cutting irons with different bevel angles, etc’ that cost a mere £60-100 a pop. I think that that’s quite a luxury for most woodworkers so I really do not want anyone to think that this will make anyone a better woodworker. I never saw a man use a bevel-up plane in my apprentice days even though they were planing end grain often enough most days. I say all of this only to put things in a bit better perspective! if you have disposable income spend what you like on what you like. If you don’t then be discerning and put your money in the essentials. No one should ever think that a bevel-up plane does as much as a bevel-down one. it only does a small fraction of what the bevel-down plane will do but a bevel-down plane does everything a bevel-up version will do.

With a well-sharpened and correctly set plane, bevel-up or bevel-down, end grain readily planes no matter which way the plane is pushed from simply because the plane sole is perpendicular to the long axis of the grain. This effectively makes the cutting iron cut as directly as possible across the fibres because the wood has zero continuous grain that in face-grain planing can dip and dive in any multi-directional way it chooses according to its grain growth. The unpredictability is because in 90% of cases you cannot see these dips and dives and switches; we generally hazard our best guess at it. Hit rising grain and it’s as if you took the switch-back too fast. The grain is ripped from its rootedness in the main body of wood beneath and a repair is most likely too deep to fix. How would you fix it? Funnily enough, always with the bevel-down plane you should have used in the first place. A bevel-down plane rarely tears anywhere as deep as a bevel-up plane will unless it’s badly set and not sharp at all.

I am always surprised (and humoured) by woodworking lovers of bevel-up planes who tell me to change out the cutting iron for a steeper-pitched one. They never stop to think that these things are almost always unpredictable and the damage has already been done. They don’t live in my world of real making where the bevel-up plane is so very restricted in its functionality. Do I own bevel-up planes? I do. I own two modern ones and then the most beautiful vintage mitre plane from somewhere in the 1800s. Do I like them? I do. The reason I share these things is not at all to be ugly or discredit fine people making planes but because mostly they are unsaid by authors and makers of fine furniture and if I don’t I am guilty by default.

Most router planes are low-angle bevel-up planes with dedicated and limited use. Because these bevel-up versions work with the blade suspended and therefore without a bed to sit on at an angle, the blade presented to the wood needs only the smallest relief angle beneath the blade. Their main function is to level the bottoms of different types of recesses to ensure evenness and then too parallelity to the upper surface. They are ideal for recessing hardware such as hinges, catches and so on. In use, they work more like a chiselling pare-cut.

Though we refer to surface trimming with chisels as paring cuts, and we can use just about any chisel to pare with, we also have very specific chisels that are called paring chisels. These chisels are long-reach chisels designed to reach into inner surfaces such as long dado-housings or pare cutting a few more inches into the centre of a board and the like. A paring chisel is long and thin and comes in various sizes for the different widths of dadoes, etc. A couple of other tools will work well for paring but are is seldom spoken of.

On an open surface, both the bullnose plane and the hand router will usually take care of levelling the excesses of a protrusion. So-called chisel planes are also available but hardly worth the money at all. Better to go for a bullnose with a removable front if you think you need one, that way you have two planes in one with the highly essential bullnose plane to boot. Can’t lose! Then you also have the cabinet scraper and the card scraper to follow up with after any chisel work.

Also, remember that it is good to practice trimming protrusions with a bevel-down ordinary bevel-edged chisel. It comes in handy to own this skill when in a bind. Mostly we lock the chisel to a rigid contortion of hands, arms and upper body and shoulders and jab at the protrusion in short repeated stabbing actions. We can also use a chisel hammer. Watch for grain direction and work from the best side so that the split cuts rise from the surface of the wood and don’t nose dive deeper than the surface.

Bevel-edged paring chisels are about twice as long as a regular bevel-edged chisel: about 9-10″ long is standard. In the days of pattern making, paring chisels and paring gouges were used extensively by pattern makers for making moulds of every kind used for sand casting molten metals. Plastics shaped and moulded by CNC machines and now 3D printers have replaced this craft completely. Paring chisels are very thin and can be moderately bent to sit flat to the wood for highly refined paring cuts near to the protrusion but many inches from the handle. I would suggest you never resort to using mallets on paring chisels except for the most gentle of taps. They can buckle and crack or even snap.

Surface trimming tenons with paring cuts from a chisel allows for very variable depths of cut and is especially well-suited to cutting across the grain as shown. Pare cutting gives you a very high degree of control because of the length of the flat face of the chisel where you can incline ever so slightly to reduce the height of protrusion very gradually down to the final levelling stroke. If you have a lot to do it works well but you can combine this with the use of the bullnose plane level with the face of the sole to take that final pass. I do this when I have many plugs to trim. Another trick is to use a regular bevel-edged chisel bevel down with the cutting edge a millimetre or two above the final surface, pop it with the chisel hammer to check for grain run and then final trim with the bullnose working according to the grain.

Abrading to different angles to establish a primary bevel is best done with a honing guide. They usually keep the tool square and allow good control for applying even pressure to the abrasive through the honing guide. Of course, it is faster to establish the skills of freehand sharpening and honing but that comes with time. the honing guide helps you to develop muscle memory for honing and today I always hit the mark without using the assistance of a guide. Does that mean I don’t use a guide? Most of the time I don’t, no, but if I have a lot of correcting to do, say after a longer class of 15 students, I will use a guide and even a grinder if they are far out.

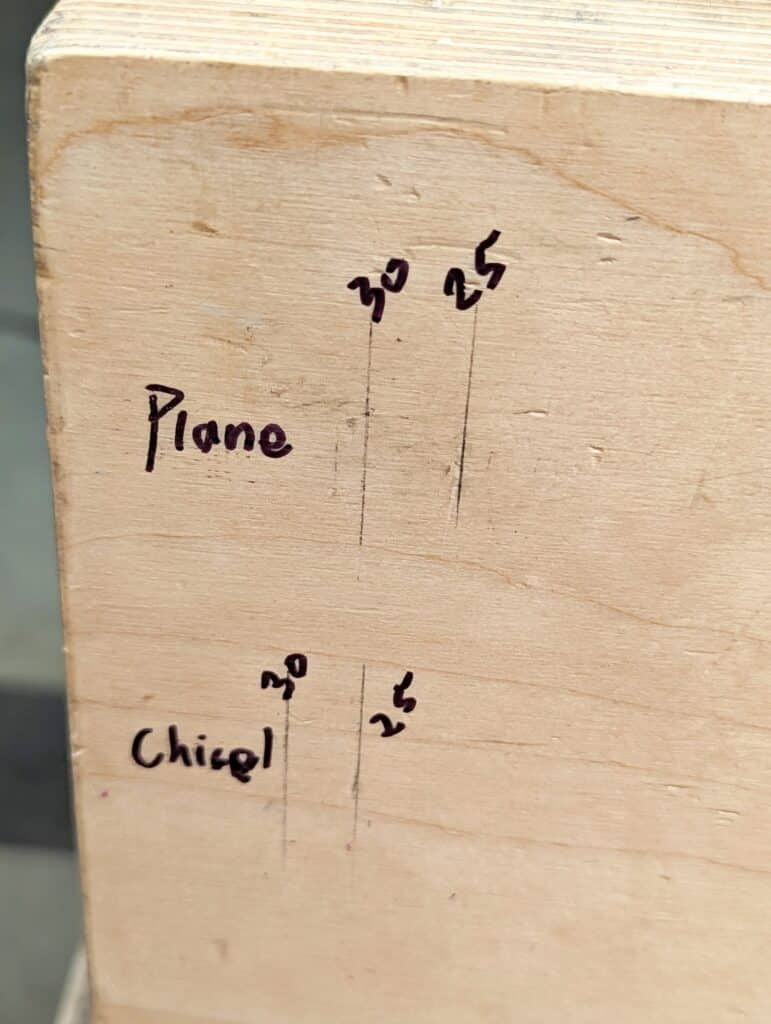

In the day-to-day of my work I have four marks on my workbench even though I do not advocate double bevel sharpening as in primary and secondary bevel or so-called micro-bevel sharpening. The marks are a quick reference for setting the chisels and plane irons to specific angles. By bumping the edge of the honing guide up against the edge of the bench apron I can slide the blade to the correct distance, cinch tight and go straight to the appropriate abrasive. I have yet to find anything quicker.

To set up this system, install the tool at the appropriate level in the guide (this Eclipse guide has two steps, one for plane irons the other for chisels. That’s because of the different widths needed) and slide the tool along with a protractor set to the appropriate angle; see below. Lock the blade in the guide and place the honing guide against the end of the apron. Mark that distance on the apron and all you have to do in future is set the plane in the guide according to the mark on the apron. It is generally accepted that chisels, planes and spokeshaves are first abraded on a coarser paper to establish the 25º angle the full width of the bevel. By using a protractor angle finder you can set the distances of 25º and 30º on the bench.

Because chisels are narrower than plane irons, the honing guide has a narrower holding part beneath the plane iron recess on the guide. Because of this, you need one setting for chisels and another for plane irons. Hence the two holding areas that can seem confusing as to reasoning.

Paul,

you say “We can also use a chisel hammer.”…

Is “chisel hammer” a tool, or is that a typo and it’s a technique, just using a hammer on a chisel?

Matt

Yep it just means tapping the butt of the chisel with the kind of mallet or other soft-faced hammer you’d typically use for this purpose. I’d hesitate to use the word ‘chop’ in the context of trimming a plug, as it just requires a gentle tap, but more force than paring/pushing by hand.

Paul I’m a long time reader and have read many of your posts about bullnose planes. So I bought one and do enjoy it. But I have a hard time using it where a shoulder plane might be better due to the small registration infront of the blade. Like when I’m adjusting a tenon cheek or should. Could you help me out and elaborate so I don’t go out and buy a shoulder plane. Thanks!

Paul – and other well-known woodworkers plus myself (not well-known at all) – recommends the Thorex 712R as a wonderful all-purpose hammer around the shop.

I have one with one rubber and one nylon head. I use it as a chisel hammer, where gripping it differently and/or using the heads to suit the task at hand varies the “punch” so to speak.

I tend to describe it as “the nylon head moves A Thing(tm) 10 mm. The rubber head moves said Thing(tm) 1mm”.

You can use a claw hammer as a chisel hammer if you want to, but don’t expect the best experience or results from it. 🙂

Some folks like the round mallet, which are used by wood- and stone carvers. Personally, I feel more in control with a flat faced hammer. It’s a personal thing, really – as for example round, straight handle on a gents saw versus the “pistol grip” type.

Look for Paul’s article about the Thor / Thorex 712R. I highly recommend it myself, and I would urge you to go for the wooden handled version. I bought the nylon handle version first. It has now been demoted to the all-round beat’em up thingamabob I use for anything and everything besides woodworking. 🙂 So not a total waste of money, really. Again, personal taste here.

This is a great article. I bump into all these long articles other places about setup minutia and myriad types of plane irons and devices. In a sense, it is great. I enjoy learning details and I have, in fact, learned useful things. Nevertheless, I can’t imagine how I could get any real work done (let alone enjoy getting it done) if I were constantly worrying over secondary bevel angles, swapping out plane irons, switching between a dozen different planes, etc. My own experience is nothing compared to a lifelong professional like Mr. Sellers, but my more limited experience over the last half dozen years aligns with everything shared in this article. A sharp bevel down plane works wonderfully for me almost all of the time. Likewise, chisels sharpened by hand to a bevel in the range of 25 to 30ish degrees also work perfectly almost all of the time. I am able indulge in luxury items, and I do find specialty planes are nice to have on hand for odd tasks. I have a three-quarter inch shoulder plan that is great when I really need to finely tune a thin edges. It easier to balance and the weight is useful some times. Now and then it is helpful with end grain, and it is also great for cleaning up inside corners in long recesses. I have a bullnose that is likewise helpful in many odd jobs. Still, these are tools that generally sit on the shelf and I go to them infrequently in special circumstances. The tools that inevitably find their way onto my bench within hands reach when working are a couple of baily planes (#4 and #5), a straight edge rule, a regular combo square, a small combo square (convenient for checking depths and other things), a marking knife, a pencil. Often a marking gauge or two ends up on the bench, along with a chisel or three, and a card scraper. The specialty planes come out from time to time, but are the exception to the rule. I mostly free hand sharpen, but a simple and inexpensive honing guide is totally worth having for occasionally truing up an edge to a known angle or very occasionally adding a secondary bevel for something. Even my limited kit ads up to a dozen or so tools in frequent use. If I added multiple plan irons and constantly shifting bevels and super precise non-freehand sharpening to the mix I can’t imagine how I’d ever achieve the happy complacency (uncritical satisfaction) from flow of work that is so rewarding. Note, that complacency here doesn’t mean not paying attention to outcomes- it, in fact, means quite the opposite and amounts to allowing the mechanical process of work to flow easily so that one can truly focus on outcome and effect while in motion!

Thanks Paul. A bevel up plane hasn’t tempted me. When money was tighter, I had no choice but to use my bevel down planes for everything and they work quite well. As such, I don’t see the point in adding another plane.

I would like a long paring chisel in which I would hone it to 20 degrees for those rare times I would use it but I am in no rush to buy one. If you had to pick just one size, what would you go with? I’m thinking 3/8 or 1/2″ might be a good choice.

Only this past summer, after 6 or 7 years of woodworking did I buy a block plane. I don’t dislike it, but I could easily do without. Over the years, I’ve tried a few other “non-essential” tools. For the most part, I am underwhelmed with them. Many of them get used once a year max which seems like a waste of money. I could always sell them if need be but haven’t been a rush to do so. I would rather have a second set of bevel down hand planes than almost all of these non-essential tools. What you teach and have put in your book is spot on.

Hi Paul. A comment only vaguely related to your latest article but relevant to sharpness and blade angles. Of all the tools I’ve found the cabinet scraper the hardest to get properly sharp. I would have put the router in a similar bracket, but I think I’m getting better at this one. But the cabinet scraper remains something that eludes me.

I’ve used your video guide of a 45’ groove in a block. I’ve got a proper burnisher and diamond paddles. I’ve tried pressing hard and pressing lightly with the burnish, putting a heavier and lighter curl on the turned edge. And I can get some shavings from the end product, but they are flaky rather than clean, and the surface left isn’t like a planed surface, more one that’s had medium sandpaper over it. It’s frustrating as I so often need to use this tool – it’s hard work using a card scraper over larger areas!

Any suggestions as to what the common errors are with getting to grips with these tools? Thanks as ever for your guidance to so many who follow your work. Alan

Same here.

For me the trick was to really lower the burnisher only to a very slight degree from pass to pass. I found no need to press hard, no need to run quickly but to lower at very tiny increments. Best Christian

BTW found the iron of the veritas scraper was not flat. veritas service was helpful and said it should be flat and offered substitute. thought makes no sense to send from Canada so initialised as a plane iron according to video of Paul.

PS. actually usually make a couple of strokes then lower ever so slightly and so on. I am also using the small guide paul shows.

I had various success sharpening my cabinet scraper too, but last time I had to use it I had quite amazing results, finaly up to what I expected from the tool, that is continuous and thick enough shavings in many pieces of cherry with akward grain that I had to refine to make picture frames. I found out to things, that will have to be confirmed next time I sharpen again, but that may already be useful. First is that I went down almost to horizontal with the burnisher, using light and successive passes as said above. Second is that I set up the blade quite shy above the sole surface, and tightened the knob enough to achieve a good camber. Often times I had issues with shavings coming more from the side of the blade than the center and some chatter, this times after setting the blade flush with the sole on a piece of flat wood, I pushed it back just a bit from both sides with my thumb before tightening and setting the camber. On my woodriver scraper this requires a screwdriver as it is not well designed and doesn’t have a “winged” knob to set the camber…

Thanks to you both. I will try what you have suggested.

“CNC machines and now 3D printers have replaced this craft completely.” I knew a pattern maker when I was a teen. When the steel industry in my area died, all those guys lost their careers. I helped him put an addition on a house (work he was doing to keep the family fed) and later he was doing landscaping. Imagine being a pattern maker one day and then being on a shovel the next. Quite a change in type of work. I knew a couple other guys who made molds for thermo-forming plastic laminates. I never realized it at the time, but everything considered, those guys probably came out of the steel industry pattern making trade.

I have both bevel-up and bevel-down planes and haven’t experienced any differences in cuts that have not been down to sharpness of the blade or to the chosen angle of the bevel-up plane blade. If a plane has done damage to the surface through tear-out, it has always been up to my not having checked the wood properly first. The only two differences I have found for me personally is that I personally find my bevel-up planes somewhat more easy to adjust and that I like their lower centre of gravity. I am also in the process of procuring a japanese plane. It’s mostly out of curiosity to get to know different techniques, which I often feel triggers my thoughts on how I can improve my own personal work.

May I digress …when I was younger and even more naive [about a year ago] I procured one of those Bedrock pattern planes [Luban]. Now I grasp better what I’ve done wish I hadn’t, but pragmatism means Put up with it for now…that means from time to time, removing blade, sharpening then replacing it. Despite trying not to upset its equilibrium, every third or fourth take-down, [rotary adjuster settings perhaps] must go awry and I waste much frustrating time ‘fluking’ that plane’s one and only workable position – an application of ‘moving target effect’ I guess, as Paul has pointed out. Writers have flirted with Bedrock in various posts within paulsellers.com and elsewhere but I can find no detailed method anywhere re how to subdue these crudely-made, difficultly-adjusted pieces. Has anyone any advice apart from “sell” please? First ever tear down I tried non-Bedrock plane parameters however realized the error of my ways eventually.