Ordinary Things …

…are mostly taken for granted!

Inventing new things, many things come to us in the midst of designing the things we need or design for others. Introducing them then benefits the many and usually leads to a developed invention of one kind or another. Being accepted across a broader platform makes it common and often leads as a sort of entitled possession whereas at the time of invention, the idea likely cost that person a great deal in risk, anxiety, finance and more. That’s why I have spent some of my writing and teaching time defending the brilliance of Leonard Bailey in his invention and development of the now highly ubiquitous bench planes he designed and perfected. His was no overnight development. Coming up with moulds for casting metals in the pre-plastic, pre-3D printer era meant carving and shaping wooden moulds by the dozen, trials of components all the way down to the weight of the plane, the thickness of the cutting irons, the type of steel alloys and much more. Engineering’s changed of course, just by the use of CAD alone where incremental changes can fine-tune any design by the merest tap of a key or two. Not so 150 years ago. I may well have invented a few things in the old-fashioned way and without computers. I do that every day even now in designing my furniture with pen and paper.

The nearest I get to a computer is the calculator on my phone to convert awkward imperial fractions to more uniform metric and back, multiply and divide less standard figures, things like that. In some cases, I’ve changed the intended function of one tool from one purpose to perform another. Today, I see that almost all of what I have, enabled me to achieve amazing results in my designs and work and what was freely given to me by another could so easily be taken for granted.

This morning I found myself marvelling at simple things that transformed my work and my working. I’d been struggling with the last 1″ of my quick-release vise that disengaged just when I needed it. I’d worked on it three times to free what seemed obvious. Each work improved performance in many ways but that last unclick to lock the threads in place just did not come. Truth is, my Woden bench vise, quick release, is my absolute favourite. I also love the Record QR vises too. Don’t let anyone persuade you differently. These are amazing vises. Quick to adjust and they have often held an overhanging tabletop six feet and more beyond the vise jaws with no problem. This Woden 189B No3 is my second one, having replaced my previous ancient one that stood the test of time through 80 years of daily use but I pensioned off and will keep it safe as I do with some other tools and equipment. To give you some idea of what a bench vise means to me, try to imagine tying your left hand behind your back and working with hand tools. With machines, you can mostly do this but with hand tools, you would need some prosthetic solution.

As I opened up my bench vise in search of anything that could jam at the closing point I could see no evidence of conflict. When I slid it closed with the lever pressed for a slide rather than engaging the threads to the half nut something hit me.

Extending from the QR lever is a 1″ mild steel flat bar that engages a cast metal rod with a notch in the side. In the near-closed position, you cannot see this element working because it is so enclosed. My gut feeling was that the bar was slightly wider at this point so I disengaged the bar via the split pin from the spring housed in the vise. I then ground off a millimetre from each side of the bar along the length for about three inches and then filed it to round again. It worked. I adjusted the spring in the process and once everything was back in place the vise was a true joy to use again.

Appreciation is a small thing and small things are seldom appreciated because, well, they are so taken for granted.

So there you have my first appreciation of a valued support — my third hand that simply needed a minor action on my part but that was undetectable and without my gut feeling it might have gone unchallenged for many more years. Who said never to trust your gut feeling? Possibly a scientist who most likely has gut feelings leading to good outcomes all the time and then claims science as the answer to all things.

Planing 30 pieces of oak can sometimes seem daunting. There is no question that it’s quite a lot of work to engage in and it does take time. Anyway that you can minimise output here is always welcomed but machines are out of the question for a large percentage of woodworkers on an international scale, but then too even for those living in the USA and Europe too.

The thoughts and feelings came as I prepared the wood for my upcoming projects. The first amazing tool was the system I use all the time for preparing my wood. With three planes costing almost pennies when compared to some so-called premium, all-metal planes replenishing the market, I take rough-sawn wood to a dead-flat surface in a matter of two or three minutes per face and a minute or less per edge. Even so, that’s still four hours of rigorous working out for upper body, heart and lungs, etc. I didn’t invent the planes nor did I invent the system and sequence for using them. They came from men working in an age when only wooden planes were used. The sequence was common knowledge for 300 years as far as I know, but it was carrying over the methodology into the world where all-metal planes had replaced all-wooden ones. So it began somewhere in the late 1860s. I simply saw the same potential and adapted unlikely planes from smoothing planes to scrub planes and then rebate planes to deeper-cut narrower scrub planes. The end result gave me an astonishing speed of wood reduction to take my boards at a faster more productive pace and with enlightened ease of working at that. Necessity might be “the mother of invention” but adaptation might in that case be the father of adoption. By adapting and adopting I simply meant converting them or adapting them to perform other tasks that might currently be relegated to machining processes more than ever before. It’s all too easy to dismiss hand working to a bygone age and not realise that it is the answer for many woodworkers if they would only understand that it doesn’t take that much to master the processes and then too realise that the cost pricewise can be a fraction of the power router and the router bits needed for machining.

Most of the tools I use could be something like the way I often saw down the sides of groove walls to make for easier ploughing with a plough plane in wiry-grained wood. Sometimes when the wood is really awkward I will chisel-chop the bottom of the groove at half-inch intervals so that the cutting iron engages with greater bite, pulling itself to task so to speak. I didn’t invent the strategy going from scrub through different levels to a finished surface from the initial rough wood.

I did take the #78 plane and make a mesmerising scrub plane that is more effective than any I know of. I actually trued up and thicknessed 30 pieces of oak. I think the strategy saves about fifty per cent of my time. No small amount in the grand scheme of hand-working my wood. lots of people think I switch to machines when off-camera. Things like tablesaws, jointers and thickness planers. I don’t. I don’t even own such equipment and no one mills wood for me generally. I say generally because one time in the last three years I had a piece of oak ripped and planed because I made a mistake on the wood I had and ran out of time for an episode we needed to conclude.

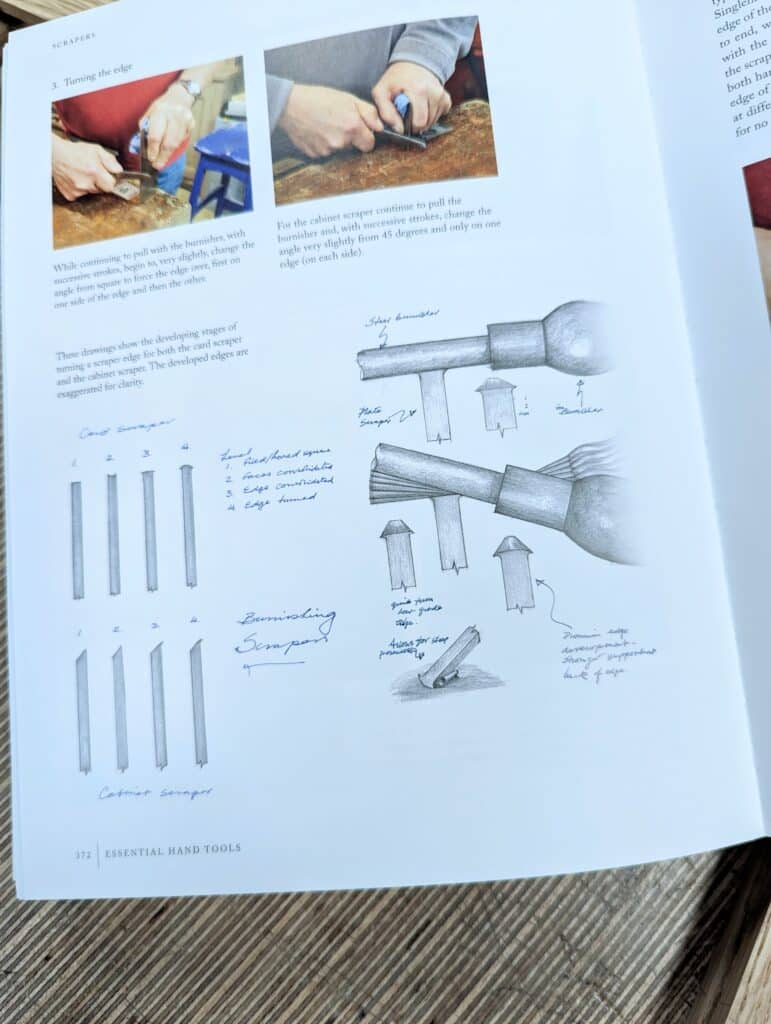

The scraper is a most remarkable work of art and remarkably misunderstood and underestimated too. I write about this in my boo Essential `woodworking Hand Tools extensively simply because people think scrape and burr as crude efforts like scrubbing of dirt and rough, filed edges when neither is true at all. It would take too long to write about here so you will have to read the book one day to fully understand the total dynamic of developing the most sophisticated cutting edges used in woodworking. There is no grain type that these two tools cannot create superbly smooth surfaces too. Think slice cutting rather than scraping and turned edge and not burr and you enter the work of refinement ahead with new understanding.

We all come up against grain that can never be planes regardless of the plane type, the direction of planing or the techniques we use. Sellers of planes give the impression that no grain can defy their planes, the cutting irons and so on. It’s not true and it’s not practical. The #80 scraper is the very fastest answer to any and all awkward grain no matter the wood type. You MUST learn to sharpen both types of scraper which might take less than an hour to master and once you have it you feel like you have entered heavenly realms in woodworking as the surface is cleared of its torn-ness and you see the reflection of success beneath your hands.

So I conclude my full appreciation for some remarkable people who unknown gave us the quick release vise, the woodworking planes and the scrapers we so rely on.

I purchased my first Stanley 78 plane on eBay along with a spare blade.

The first reason I bought it was for fielding panels for a 6 panel door I’m making which the fields on each side are 1 1/2 wide. These are double sided panels, I couldn’t think of any other way to make them. The second iron will be to make a scrub plane out of it when needed.

I got a good deal on the plane by the looks of things, it’s complete and not pitted with rust. I should have that on Monday next week. I really enjoy learning how to use new to me tools.

This door project is one of many firsts for me from hand chopped mortise and tenons, moldings and of course hand planed panels. I have five more to make and I know they will go much faster than the first one.

I’m sure I’m not the only one who would love to see your notebooks published one day. No annotations or footnotes or editing, just copies of each page. The amount of knowledge, experience, and creativity concentrated in those volumes would be astounding to read, and very nearly priceless.

I totally agree.

I’ll third the motion! Yes, please … but all in good time.

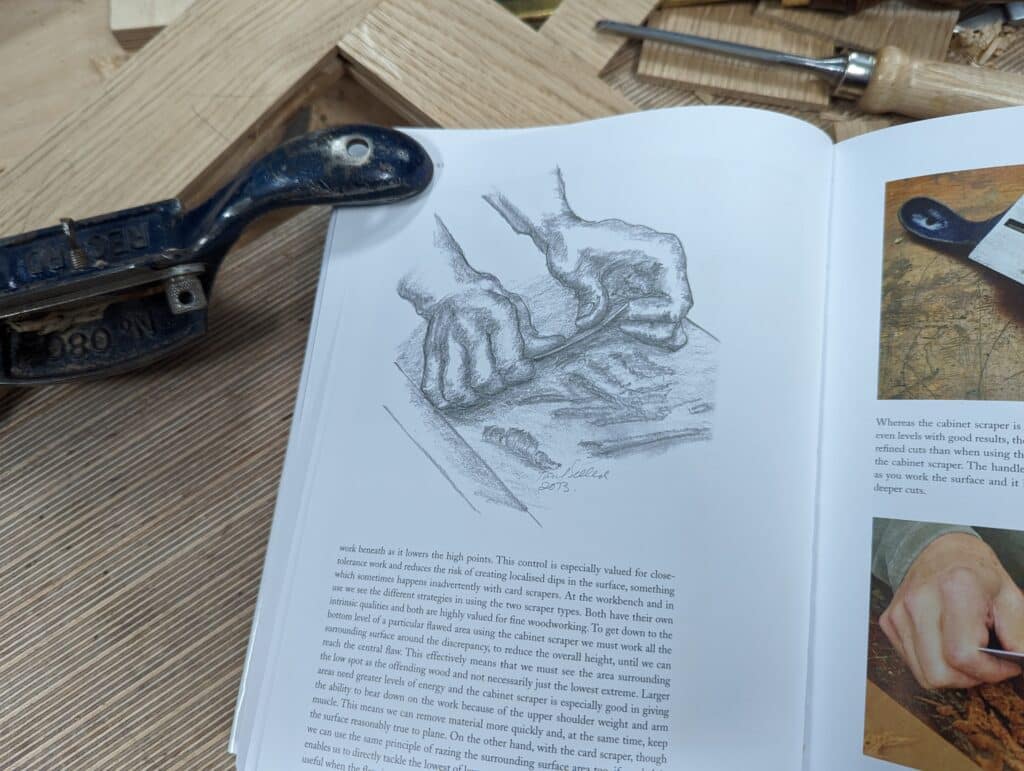

Paul, the last picture which is the close-up of you using the card scraper, shows you using the heel of your hand to help bend and push the scraper. I love using the card scraper. It’s one of my favorite tools to use. But I’m having a hard time now due to arthritis at the base of the thumbs (I’m your age). It hurts. I’ve tried using the scraper as you show in the picture but I have a hard time doing it that way. Any suggestions? Thanks.

I think the lightly curved scrapers help a great deal because with the curved edge they need much less thumb and hand flexing/pressure if indeed they need any. I just make my own by grinding and filing a radius. Sharpening is otherwise the same.

Update: I have now posted a blog on how to make my card scraper holder.

Greg, alternative to Paul’s suggestion, you can also buy holders for card scrapers which can be set to bend the card via a central thumb screw. I’ve never used one so can’t say how effective they are and I imagine you lose some feedback and ability for quick fine adjustments during use, but it might be an option for you. I know Veritas make one, but expect cheaper versions are also available.

use the search button (little magnifier on top of the page) to find the blog post “More than a scrape” dated 12 April 2022.

It can be shaped with a file but it will be a little more tedious than with a grinder.

I have a Parkinson vise, restored from eBay. Was about £30 I think. It works so much better than anything I’d previously experienced. The grip that it gives is just amazing. It’s probably the best purchase I’ve made, although it was very rusty and needed a lot of work! The genius mechanism that you describe so well was new to me, so taking the vise apart to clean and re-install was incredibly valuable and enjoyable. I’m quite a hands on person, but I’m not one that can just look at something and immediately see how it works, so the simplicity of the design really helps. If anyone is looking to take something apart and put it back together, the vise is a great project, with an unbeatable end result.

Thank you Paul for this nice post, instructive and entertaining in equal measures.

Cheers,

Michael O’Brien

Is there any reason that a number 4 with the same radius as your 78 wouldn’t perform as well? I realise that the front of the blade opening would need attacking with a file.

My reason for asking is that I really miss a front handle on my 78. I have debated making one (similar to the Woden version) to fit in the front blade position.

My present scub is an Acorn, which is fine for this purpose. i can pick up another for less than the price of a second 78 blade, so it seems financially viable. It is a question of the unused width of the body being a hindrance as you work across a board, resulting in tilt?

Hi Keith,

I know this is an older post, but to your question about grinding a tight radius on the iron of a number 4 bench plane to make it into a scrub plane; the answer is that there are limits to how much you can do that. A mildly cambered iron is fine on standard bench plane but if the grind has too much curve you can no longer retract the iron to a usable setting. The iron adjustment-wheel/lever acts on the chipbreaker (rectangular hole) not on the iron itself. The chipbreaker can not overhang the curve of the iron’s cutting edge or it will jamb with shavings. So with a tight curve, the chipbreaker must be set back on the iron so far that the iron sticks out the mouth of the plane even when fully retracted. I’ve seen some folks also grind the chipbreaker to a curve to account for this problem, but that ruins it for normal use and can still leave gaps that will jamb with shavings. A much better solution is to install a standard chipbreaker and lever-cap from the next plane size down (so a no.3 chipbreaker/lever-cap in a no.4 plane) so it can sit farther forward into the curve. I’ve used planes set up this way for years and it’s a good solution. Hope this helps.

– John V