Considering Screws

In my recent faux pas screwing a dovetail together on a Facebook post my goal was to prove a variety of things we woodworkers supposedly ‘know‘. What was greatly evident, and I knew this to be so, was how judgemental humanity tends to be and worse still just how self-righteousness manifests itself in the criticism of others in words such as “you should never . . .” Of course, when it’s our work we can screw, nail, dowel, plug and use any secondary fastener we want to if indeed we see fit to. It’s up to us.

I wanted to tackle the idea that we should never screw woodscrews into end grain when I venture to guess that 50% of the screws we drive or indeed I drive go into end grain. My early experiences of driving screws was in the pre-battery-driven drill-driver days of the early 1960s when all we had was flat-head screws. We mostly used the Stanley ‘Yankee’ screwdrivers to drive screws in quick succession but not generally on high-quality work for fear of slipping. If the bit slipped out of the slotted screwhead the work could easily be ruined in a single push. It wasn’t too much later before the cordless drill-drivers we know today came into being and of course, everyone liked the progression they made from 12V to 14, 16, 18V and then the ever-more compact 20V versions we rely on now. The main advantage of single-handed use, combined with magnetic bit holders and posidrive screws gives even greater advantage when we assemble different projects with lots of screws to drive. Of course, the main advantage of power at the elbow has led to a certain loss of sensitivity when we drive the screws deep into the wood. We tend to set the beast at maximum speed and torque. But it’s this that mostly leads to stripping out the wood thread when we drive the screws home. As soon as the head hits and seats or full-power setting does one of two things; the head snaps off and leaves the threaded shaft in place but not pulling or the thread strips out of the wood itself and there is no ‘bite’ left in the wood. Another development in screw-making further exacerbates the problems we face.

Self-drilling screws with hardened shafts are indeed harder but also more brittle. They may not buckle under the pressures of being driven but they do snap more easily. Added to the self-drilling aspect of the centre point is the serrated edge to the thread itself. Each advancement may be an improvement but only under ideal circumstances. There can be no question about it. Unlike one commenter saying, “They don’t make’em like they used to.” Screws are highly developed sophisticated versions to what they once were. They are cheaper now than they have ever been and just about everybody you or I know has a pretty decent cordless drill driver hiding somewhere in their shop.

I think woodscrews are absolutely amazing inventions and they are better than they ever were. By saying all of this I am explaining that it is not the screw going into end grain that is so much the problem but the user with so much power at the elbow displacing the sensitivity we had when we indeed relied purely on our own strength.

I think it is twelve years ago since I made this bench stool. Though I never actually intended to use it, I have indeed used it every day since it came together purely as a prototype to test for angle, stability, height, etc. It became one of those ‘cobbler’s children‘ things. This stool version was made from two two-by-four spruce studs so very soft and not particularly good wood for resilience. Had I listened to the naysayers I would not have had twelve years of use from the stool. I’m guessing that this stool could just about see me out if I do indeed I live using it until I am 100. Who knows?

I painted the stool blue with a white undercoat for appearance. I used two screws to each rail and predrilled every hole with stepped holes so that nothing was forced, over-drilled or oversized. I can drill slightly undersized by a fraction so that the screw employs an additional friction hold as well as the threads. I hasten to add here that I m not saying the end-grain screwing is as strong as the side-grain screwing, I am not, but I am saying we should not shun this as a viable option in some if not much of our work. It will depend mostly on what we plan to use the project for. And remember that we can compensate further by using longer screws where the wood allows for it.

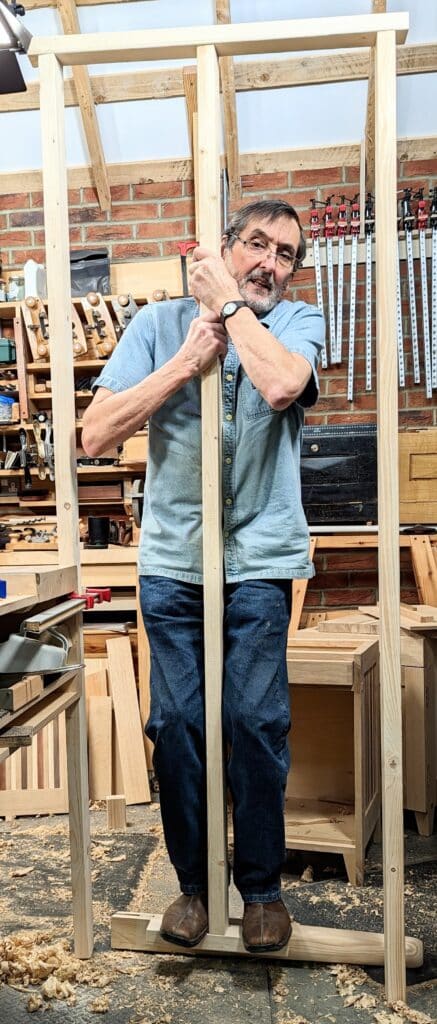

Above is a more recent stool we use in the classes for students to use. That’s a day or so a month if that. It should last for a hundred years at this rate of use compared to my blue version. I am in no way suggesting pocket hole screws for furniture making nor am I saying screwed-together pieces are a good substitute for proper joinery. I hate even the term pocket hole joinery; that’s the exact opposite of what it is. But there are times when time disallows the full monty. Many of my prototypes are simply screwed together to express a concept and to save time, energy and money. There is nothing wrong with that.

The extremes in woodworking often remind me of the extremes in religions through the ages, even into our present age. The word legalism comes too regularly to mind much of the time. We do tend to want something of a religious demand on precepts and concepts like the angles for sharpening bevels on edge tools or dovetails. In my world, I work somewhere between 20º and 45º depending not on mood but wood type, pressure applicable to task, angle of presentation and much more. The law of thirds seems just silly to me in the same way never screwing screws into end grain is silly or believing that a dowel is stronger than a screw when I want the pulling power of a woodscrew.

Here was my experiment today. It took me ten minutes and I felt it was worth the doing. I made a mock door frame, hung a two-by-three spruce stud from the opening two inches above the floor by a single screw into end grain and stood on a step piece I had screwed into the end and into the end grain. I tried it three times stepping off a two-inch high board so I could get even pressure to each side of the stud. I weigh 75 kilos (165 lbs) `and the screws top and bottom held fine even in ultra-soft spruce. There was no glue. These interesting experiments bring enjoyment to my work with you. In the Facebook post on screwing the dovetail, it was the legalism that I know we are all capable of. Questioning authority, the concept, likely originated with Socrates, but there was much questioning taking place in the 1960s when government used manipulations and machinations to control people into thinking bigger numbers of people suggested the right path would always be taken by the majority. In the few comments countering my desire to use a screw in the middle of my dovetail, there were 12,000 likes and a couple of hundred criticising the use of the screw.

My wooden bench stool prototype has 32 x 3″ screws holding the angled butt joints together. How that translates into the applied pressure to each screw with 75 kilos (165 lbs) I’m not sure. The pressure on the stool screws are never direct pull as in my experiments on the dangling stud. Maybe in this article, I am asking other questions such as why go to the trouble of good joinery when screws will be good enough. Why take so much time hand-cutting joints that take days when in an hour or two you can have a stool together and in use? None of this really, more that there is a place for prototyping pieces and skimming off the top to get something together. End-grain screwing is good in my book as long as we are responsible for where we will; use it. We must consider one thing that screws really don’t take care of and that is the constancy of expansion and contraction. I will never be an advocate for screwed-together furniture. That’s just lazy and never a good substitute for good joinery in well-made pieces.

In all of this, I in no way want to discount the reality that screwing wood screws of the correct and appropriate type through and into face grain is not much stronger than screwing into end grain. It is considerably stronger in 95% of woods and wood types and that difference is not in any way questioned. So many things become legalistically imposed on others as do’s and don’ts rather than to consider more the appropriateness. In the case of my dovetail and the reasoning behind it was a perfect solution.

A decade or so ago the wind pulled out the hook fastner holding our wooden garage door ajar. The sudden shock on the tenons broke them. I fixed them by driving 6″ screws through the tenons and into the frame after drilling suitable pilot holes, to pull the broken joint back together.. This “bodge” is still holding strong even though the screws were entirely in end grain.

For some reason I still remember a conversation I had nearly 50 years ago about the merits of coach screws. The person I had the discussion with rejected coach screws in favour of coach bolts arguing that unlike woodscrews they had a parallel shank. At the time I wasn’t convinced. Modern woodscrews, like coach screws tend to have parallel shanks. The traditional ones would not break at the head, and I assume that the tapered unthreaded shank would give extra holding power when joining two pieces of timber, I assume. I presume the lack of taper is to assist driving and is thus a compromise, as well as being cheaper to make.

However, I do prefer using modern torx head screws.

I left a comment on (Making a router plane from a kit – ( YouTube) video)), you asked that I contact you. This is the only way I know how. I hope this helps. Karol’s Kakes

Mark,

If Paul doesn’t notice your comment here, I suggest you go to the Websites link in the header of this page. Go to the woodworking masterclasses page and there is a “contact us” option there. I think that the Rokesmith company is responsible for both masterclasses and router kits, so you should get someone that can help you or point you in the right direction from there. Paul, please delete if I’m wrong or unhelpful in my attempt at helpfulness, I’m only responding as I know you’re a busy man who receives a lot of comments!

So much fun learning to work with wood. You, Paul, are such an inspiration. I have just finished, essentially, a Moravian workbench. Many errors yet much learned, had never chopped a mortis, nor cut a tendon or made a stretcher to strengthen a table leg. I now use your clamping methods for planing boards. On the subject of using screws, I pre drill for each fitted part using Torkshead fasteners driven by a DeWalt battery powered drill, set first below a seating torque level. Then increase torque until proper seating is achieved. If the fastener needs to be below the surface, I drill a countersink hole first. I keep several pounds of fasteners always on hand in many different lengths. Thank you again for all you do.

Two words that always prompt suspicion when I read an article on woodworking (among other topics): ‘always’, and ‘never’.

Your article is quite thorough, but perhaps too apologetic. You do what you do, the way you do it, because experience. Those who insist that one ‘always’, or ‘never’, convey more about who they are as individuals than they realize.

We’ve all had quite enough of ‘mandatory’ this, that and the other during the past three years; time for us all to appreciate variation in life and work, and once again learn to beware the man who is absolutely certain.

Thank you for your work, guidance, and influence.

Ignore the nay sayers Paul, it’s their lack of appreciation and knowledge that leads their lives.

Focus on the positive always!

My thoughts exactly.

Thanks Paul.

I wonder how much bigger/better both woodworking and world religions might be, if “The extremes in woodworking often remind me of the extremes in religions through the ages, even into our present age.” were not true, or so joyfully deployed by many…..

Years ago when I saw a photo of Tag Frid driving a 3″ drywall screw into one his rocking chairs, I kiddingly suggested calling the screw a “helical steel driven dowel.” Perhaps that’s away to not “offend” the righteous. I also tell people I’m a “woodbutcher” which takes the wind out of most “blowhard’s” sails.

The screw failures I have seen have been after a half century or more of use. The wood between the screw threads eventually gives way and the screw can no longer hold. Have seen it a lot on door hinges of a house. I think a lot of it happens to screws that are subject to seasonal temperature changes. The screw gets cold and moisture condenses on it and causes the wood to rot. Sometimes enough humidity will cause the screw to rust away substantially. I live in a relatively humid climate, so my experience may differ from someone in an arid region.

But a screw should hold a long, long time in furniture protected indoors, unless subject to undo strain or abuse

“I will never use dowels in my work”. Really? Could you perhaps provide an explanation? Is it because they have no pulling power?

Mainly because it is a skilless method to connect wooden parts developed for mass-making utilising butt joints which are not joints. I say the same for biscuit joints which are not joints and also dominoes. but this is my preference. People can do what they like.

Paul…ok I see that. But that type of dowelling is different than using a dowel to anchor a tenon within a mortise offset or not, no? Personally I like look and the added confidence in the joint. But then I’m just a hobbyist.

Nomenclature is everything! A draw-bore pin is not dowelled construction and neither is it a dowel. Huge, huge difference. Not at all one and the same animal, Jeff. I have no problem ‘pegging‘ or ‘pinning‘ a tenon as in draw boring.

I love learning from you. Do you have a video on making that stool? I would like to make one (using screws) but I didn’t see a tutorial video.

Look in Woodworking masterclasses: workbench stool

While searching for something else, I stumbled on the post titled “Why plywood” dated 6 October 2017.

Look at the first picture 😉

I always enjoy your wonderful writings as well as your amazing skills. A quick question: why are you opposed to the use of dowels? Personal preference or a mechanical reason? I know there are certain situations where a doweled joint is stronger than a mortise and tenon. Although the M & T is faster in those situations.

Isn’t a dowel joint a form of mortise and tenon joint? A loose tenon that is round rather than rectangular?

No. Not in any way. There is no such thing as a loose tenon in my world. If you and others like the term then use it. We often compromise beliefs which is always a weakening of conviction and we know where that leads to. we invent IKEA strategies and incorporate a mini conveyor belt factory in a small workspace like a garage. we are in different worlds, that’s all.

Perhaps I used the wrong term with loose tenon, when you talked about what I was meaning you called it an inserted tenon, when referring to repairing a broken tenon this way in 2017.

I have used this method to repair a broken tenon in the past.

My work in joinery and furniture making is about the art of work. I see craft as that art and it encompasses what we do and then too, equally important how we do it. Drilling holes and inserting dowels is a skillless pursuit as is driving screws and plugging them. That said, in some circumstances, screws will be unsurpassed because of the pulling power they afford the work alongside their offering temporary or permanent clamp replacement while the glue cures or dries. Take screws in hinges as an instance. Nothing does this better hence there has never been a substantive replacement although I do think pop rivets do a pretty good job. I make time happen for my joinery to give me both the peace of mind and the integrity I strive for.

I believe you hit the screw on the head; the right tool (fastener) for the job and balancing speed of assembly/strength/aesthetics and all other aspects of working with wood. You continue to eloquently explain to us how to do it. Many thanks. Pray maintain speed and course.

I would like plans to some of your builds, how can I acquire them? Always appreciate your skillset and gift to teach.

The pieces I make are made for woodworkingmasterclasses.com and sellershome.com. The plans are available to paying members. You pay a monthly membership fee and have access to watch all of the videos series showing how to make the pieces and so too the PDF plans for the pieces.

hi paul (or others),

i am experimenting with your milking stool. i want to make a very neat cylindrical mortise and tenon joint (not conical) for the end of the leg to go into the stool. i know this wont be as strong as usual. the bit i am struggling with is i dont want to have any bevel/curve between the base of the cylindrical mortise and the rest of the leg. i can do this with a jig and a gents saw to cut down to the circumference of the tenon where it joins the leg, but i am wondering if there is a better way (seems there must be?!).

easy on a lathe but hard with hand tools to get this really neat base on the tenon – how might you do this?

thanks a heap, paul g

I don’t think I have enough information from you but it would be too complicated for me to spend time on it, Paul. Seems as though you want something complex and of course, with that goes working it out.

sorry should have said i dont have a lathe and would love to know how to do this with hand tools if there is a good way cheers paul g

If you simply mean cutting a round tenon you can get tools that fit in a brace to do it.

Thanks Keith and Paul. Keith that is what I mean, just not great at explaining it! Will have a look for the tool and price. And actually Paul’s next article on the router plane I just read made me think I can almost certainly tidy up the base of the round tenon with the router plane if I use the round leg as a reference surface before doing any tapering. . Feel a bit silly for asking now – but I was a bit stumped and have got two great solutions to move forward now so thanks!!

Excellent blog Paul. I mean another excellent blog.