More about your knife

For more information on the woodworker’s knife, see our beginner site Common Woodworking.

There is more value to a knife than cutting Sellotaped boxes

It’s obvious from the emails that not everyone owns a specific joinery knife and is pleasantly surprised at the results in situations they have not seen before. Many obviously do not know that a knife is so intrinsic to general and fine woodworking. This is the sad demise resulting from iconic gurus in the so-called power-woodworking realms. Quite specifically, a joinery knife extends beyond joints and joint making into the broader realms of crossgrain slicing to separate the wanted from the unwanted. In most cases we often rely on machine cuts to give clean, square cuts. My outreach is to those who may never own a chop saw, may be rightfully intimidated by them or want to master skills in hand work using their own power.

Every joint made with any level of exactness often needs many knife cuts, and the dovetail joint is but one joint alone. I don’t have a dovetail knife and don’t believe in them as specific stand-alone knives. I generally don’t rely on such dedicated knives as some might prefer to. I do believe in joinery knives as distinct from striking knives because no joint can be well made without them. A joinery knife cuts the shoulder lines on all joints but for the main part we tend to think dovetails and not joinery or crosscutting and so on and so I encourage woodworkers to think joinery knife rather than dovetail knife alone.

Because knife lines are permanent, we generally use pencil lines to initially mark the wood before we cut through the wood fibres permanently with a knife. Two other tools we use that create permanent marks are the mortise gauge and the marking gauge. Again, we usually use pencil lines to present boundaries for guiding permanent cuts and subsequent cuts that cannot yet be made. These are temporary lines that prevent damage to surfaces surrounding the joint.

The Stanley knives I have encouraged the use of are excellent, inexpensive knives that get the job done as well as if not better than any other. The spear point or diamond point knives are poor knives based on engineers who mean well but don’t work wood. This knife beats the socks of all others for a joinery knife and for a fraction of the price.

Ok, my point is about the point.

The knives I advocate have a weakness. Because we are using them on wood and not paper or fabric, the tips can readily be broken off. In reality this actually enhances the knife in that what is left is a strong knife end that usually will not break further beyond this point. When the point breaks as shown, the knife continues to work efficiently with no degrade.

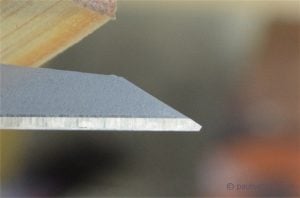

The knife at left is a new unfractured point alongside a modified point reshaped a little on the diamond plate on the right. I usually do this with a new knife blade if the point breaks off or at some time after in subsequent sharpenings. This makes the knife capable of reaching into the tight corners, yet at the same time strengthens the end of the blade and prevents further breakage.

To redefine the point, I turn the knife upside down and hone that point above the tip to a slightly more rounded shape.

To sharpen the knife edge and point is dead simple. Lay the knife to a low angle, about 10-degrees, which is the same angle the knife blade was ground at, and push back and forth until a burr forms on the opposite bevel.

When the burr is formed along the cutting edge, turn it over and elevate to 10-degrees on the opposite bevel. As long as you move from 10-degrees to zero, the edge will always be readily sharpened.

Now the knife can be resharpened as needed and I can make my crossgrain cuts in any wood.