It’s Just a Gate

People open them and leave them to slam, saying they closed the gate but they didn’t close it. I think a well-made gate deserves respect for its maker. This gate, ageing now, has wear and cracks that tell me things that others miss when they pass through it, leave the gate to slam shut and shorten its age by a third. Well, still, it’s holding up fine. I opened it and closed it without leaving it helplessly to slam because, well, again, I cared. The gate leads to a pathway following along the rim of a beautiful lake people visit for peace and recreation. Two people came to swim while others sent their dog after an orange ball. I spent some hours there contemplating future hopes and aspirations over the last four days. The people who swam swam a long way out until I could just about see two dots and when they came back they asked me why I was drawing a gate. I said I felt it needed recording and putting somewhere safe so we don’t forget the maker whose name is already forgotten or unknown. It would be a neat thing for someone to make another, I think.

I have written about the loveliness of garden and fieldgates made of wood before. A few sections of rough-sawn oak with calculated rails set at sdiminishing spacings to keep the lambs in as new-borns in Spring. Just a humble gate made by a man most likely. He’d be a man no one knew outside of his village and the carpenter’s workshop tuckeed away in some quiet corner. He might have marked his work as men often did with nothing more than a simple mark somewhere tucked away in another quiet corner of the gate he’d just made. No one knew of such things as the humility of a man-maker who chopped out his mortises knowing others would let his gate slam-to instead of closing it to save stressing the joints and splitting the wood somewhere. You know of such things when you make a gate or door.

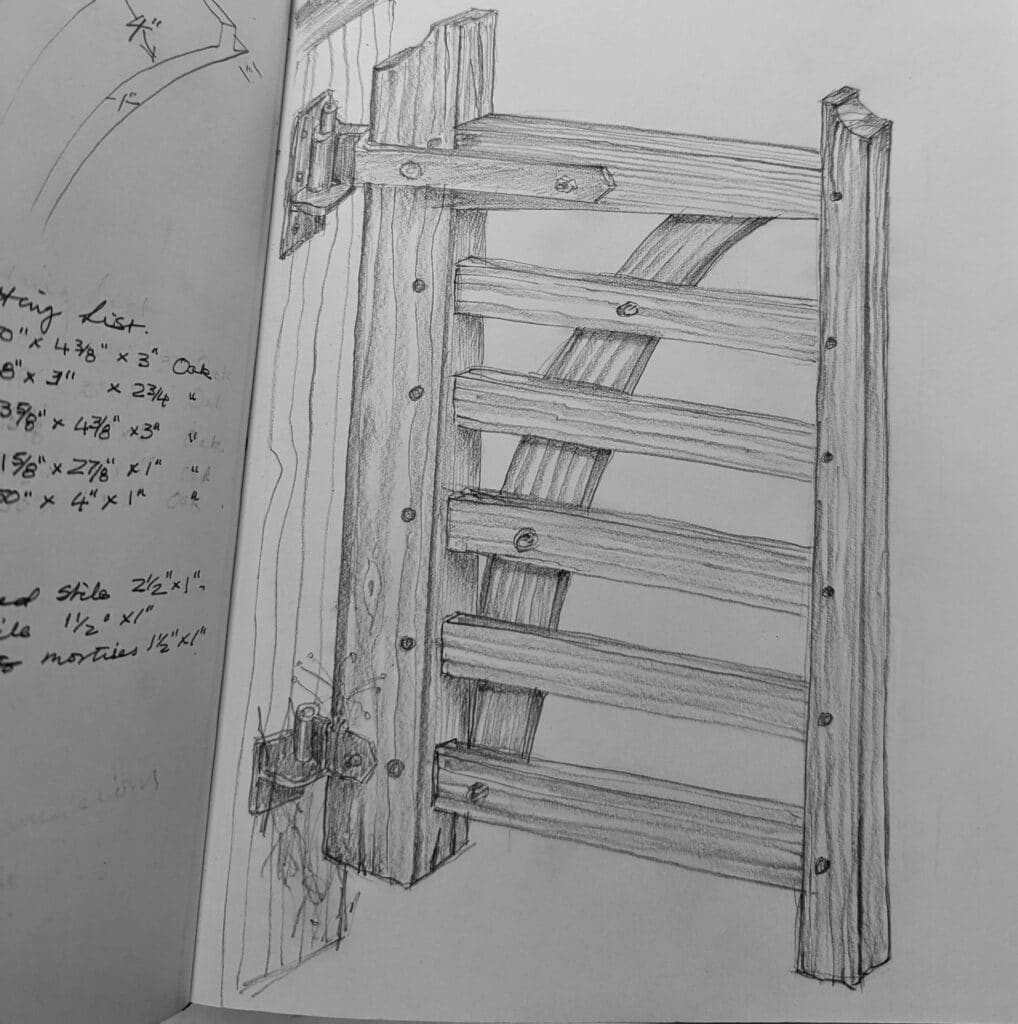

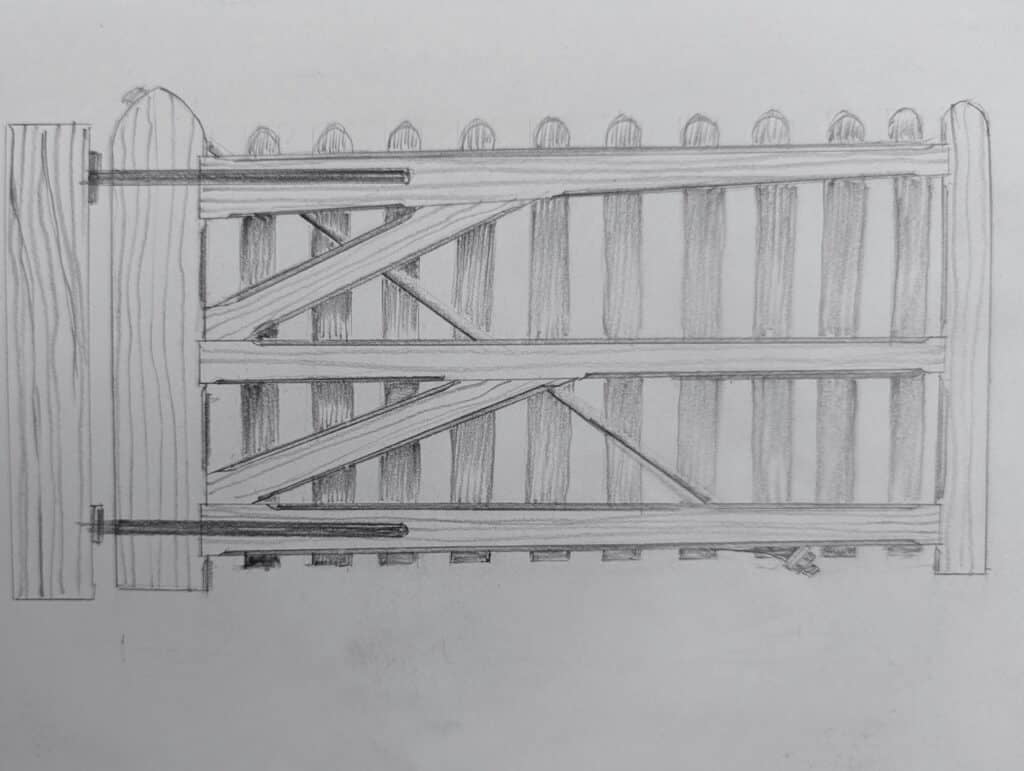

The oak gate needs no finish to it, for finish will hold moisture in to ultimately prematurely rot the wood. A pine one made of heavy sections stoutly framed has tapered rails in like fashion to save weight to the free side. The free stile or post too is slimmer still by half and then, look, see how the threaded rod passes through at so steep and long a rake angle, pulling to take the strain and give additional future adjustment to raise the free stile if the wood should sag over years to come. So small a thing made so with longevity and forethought in mind for others to own and not the man maker beyond his then three-score-and-ten.

So we look at the deeper things in making. these men built with forethought anf anticipation knowing the North Wales coastal weather that hits with great force every few days and then, often, for days on end. I love that such things were deeply considered. But then I took in the stoppped chamfers that had good reason and forethought too. Were they decorative? Not in the least. Chamfers didn’t just ‘ease the corners’ of gates like this. Not at all. On the top rail, they narrowed the width by a two-thirds span so that water could and would drain off quickly. The main reason for these stopped chamfers was to allow for continuous paint surfaces that would not break continuity on the corners through expansion and contraction of wood at right-angles.

In the past we used to use red lead paint for outdoor projects. We used nit when we made or installed wooden gutters to building before we lined it with lead to catch the roof’s rainwater. Those days are gone but had their roots in the `romans establishing theoir rule in Britain where they could. Funny when you think about. People replaced lead with plastic a million-fold. We have an incredible capacity to pollute, don’t we? When plastic first came out for windows and doors here in the UK, sales reps offered a lifetime warranty without telling anyone what a “Lifetime” was. Since then we understand that the lifespan of plastic windos and doors is around fifteen years. Just a fraction of wood. Hey ho, there you go!

The gate I drew just above is made from Redwood pine. To have a gate live long you must have a regimen of meticulously painting it. If you do that every five years or so it will last for decades but yopu must first prime the wood with primer paint and then go with two undercoats and a top coat of gloss. Oil-based lasts longest but people have erroniously believed manufacturers who say things about the environment abd the washability of water-based finishes as though they are not toxic when they are literally fluid plastic washing into the water systems and watercourses . Hard to know what to do but our influencers and activists are most likely washing their acrylic paint brushes in the kitchen sink whilst gluing their hands to metal structures and pavements with superglue or CA glue (cyanoacrylate glue) which is composed of an acrylic resin. The main ingredient in cyanoacrylate glue is cyanoacrylate, which is an acrylic monomer that transforms to a plastic state after curing. Anyway, there you are.

So here is a fairly basic gate that needed almost no skill to make and we will see how long it lasts as the years pass. I don’t think it is ugly, it just relies wholly on 30 screws and a couple of bolts that hold the hinges to the gate for the gate to hang. Of course, we understand that skilled work is in high demand elsewhere and a garden gate that takes onkly a couple of hours to make provides an economical answer. I’d estimate that it will last a decade or so which is possibky not a bad return on your investemnt. Even a fully jointed one might only last twice to three times as long in the right wood. Anyway, compared to the slate wall three feet thick the gate will need replacing many a hundred times.

Thanks for sharing Paul. My grandparents lived next door to me. My favorite gate was the one that connected the two backyards so I could go visit grandma and grandpa easily. About 10 years ago, a huge Monterey Pine in my dad’s back yard fell over in a strong windstorm and destroyed his detached garage as broke off the gate as well. All was taken care of by insurance eventually. My dad howled when they put up a newly designed gate as the old gate door have been salvaged for return to its proper place. My brother eventually re-installed the old gate door much to my and other family member’s pleasure. Simple gates can mean so much more.

Zooming in, the grain in the curved brace (first gate) seems to sweep right along with the curve of the brace. Did the maker find a wide board with curved grain crossing it and followed that grain to define the shape of the brace? It seems the wrong dimensions to have been steam bent. I know nothing about boat building, but this brace makes me think of boats.

It seems that the mortise and tenon for the top mortise on the hinge side is in tension, i.e., stresses are trying to pull it apart (as well as rotate/twist it). Is this why the hinge strap goes across the stile and long a bit of the top rail?

The brace was taken from a branch with its natural bend. Rip down the centre and then a parallel cut gives to two braces. A very common gate here in Wales if indeed someone cares enough to have one made to spec. Re the top shoulder line. The gate was made from fully green oak so shrinkage on the heavy stile is quite marked. In the wet season the swell will close up the gap whereas in the dry season the shoulderline opens up because oak will swell (expand) over a six inch width from kiln dried down to 7% up by 3/8″ and so will shrink too but not so much because wood outdoors in Wales and the UK would never get down anywhere near that low.

Going back in time when villages and farms relied on a local blacksmith and farmer. Timber was bought as a standing tree often. The art was to estimate how many straight and curved pieces could be got out of the said tree and even more difficult was estimating future demand. Many of the items made needed curved rather than straight timber. I have often wondered if curved pieces on gates were really to use up surplus timber without another use. That old way of obtaining timber died out when imports made it uneconomic.

I have often studied, whenever I get the chance, old farm barns. Often the timber used was squarish, but curved, often were a straight piece would be better. I guess that whatever was available was used.

As a teenager, I helped builders remove an old foldyard gate post. the doors were solid and heavy to retain the cattle. The offending post was showing signs of rot, and at painting time had been condemned. The had dug down about 3ft and wanted help from a tractor front loader. The post refused to move. A lot of further digging was required. When it was finally removed the base of the post was the original tree, only the part above ground had been squared off. I bet that post had been there many decades, perhaps a century or more.

It was replaced by a much shorter one, only a couple of feet in the ground and a lot of concrete. I bet it is nolonger serving its purpose.

The village I grew up near had a village carpenter and blacksmith. The carpenter was semi retired (possibly forced by lack of work) the blacksmith was fully employed, sadly both shops are now an engineer. They were a relic from a time when between them they supplied most of the local needs.

Hello Paul. I appreciate your years of experience and skill. You have taught me a great deal about hand tools and joinery, especially as a new woodworker. I finally learned how to sharpen a plane iron and how to tune my old no 4 stanley plane I bought on ebay. After a little fine tuning I started getting some beautiful shavings and a nice smooth surface on a piece of scrap. what an experience and sense of accomplishment. regarding the fences, all I can say is that I will now be paying more attention to detail when I see what most (including me) overlook in wooden structures of all kind. although there are fewer opportunities to see those older builds here in Spokane, WA. Thank you again and I wish you a speedy recovery!

James Howard

That slate wall is a lovely thing.

We all are inadvertently polluting even when we are trying not to.

I recently acquired a string trimmer which uses bright orange plastic string to cut the high grass down in difficult places. I never see any bits and pieces of orange in the yard so I wondered where all the plastic is going. What I found was the string is breaking into very small fragments so small that you can’t see them. Not much I grant you but multiply by a few million people and now you’re talking about a lot of plastic we are putting into the soil.

There doesn’t seem to be any other practical alternative although some people are letting parts of their lawn go which looks terrible. I don’t know this for a fact but that lead paint we used to use had to go somewhere when it flaked off the wood. Now of course lead paint is banned from the average consumer but it’s used today still on ship hulls. So I guess we are still polluting the oceans with lead and god knows what else. I console myself believing we will not only find better materials to work with that don’t pollute the earth and we will find ways to clean up what we are putting into the oceans , soil and air. Besides one erupting volcano makes our decades of polluting minuscule by comparison.

I’ve seen 82 Winters. In my earliest years there was almost no plastic and what there was was of the Bakelite sort. I can think of nothing that mankind has done more damaging to the planet than plastic, especially plastic used to package or contain products. Forget what CO2 might – or might not – be doing to our atmosphere and that it ‘might’ be increasing Earth’s temperature, plastics have done and continue to do more damage than anything I’ve seen in my lifetime. Made a supreme ruler for a day, I would ban plastics and destroy the knowledge of how to make the stuff. Don’t buy the lie that plastics are recyclable (for it is a lie). If it were economically viable to recycle plastic you would never encounter it in the wild or in landfills. Perhaps it ‘can’ be recycled, but truth is that it is not recycled but left to pollute.

Those of you younger than me, spend your energies raging against the use of plastics and your support for politicians who will enact such a bounty on plastics for recycling that their manufacture becomes economically unfeasible. Those activities will do far more good than going ‘green’.

I’d vote for you, Bob.

Bob for supreme ruler!

Recycling was invented by industry. That said, plastic was developed to use the byproduct from the fossil fuel industry, which would have otherwise been a waste product. The thing I dislike about the recycling myth, is that nobody every talks about how many times something can actually be usefully recycled and what the lifespan of that future product is and where it ends up. If the energy-intensive recycling process adds only another two years (for example) to plastic, then is that of any relevance in a material that lasts several hundred years in our environment? Or even ten years? The conversation always revolves around “single use” plastic, and how we should get rid of it. But doesn’t all plastic end up being a “single use” plastic after a few goes on the recycle wheel? If it wasn’t being used as single use, would we just end up with a giant pile of “no longer recyclable” materials which would go to landfill/ the seas?

Anyway, the hardware for my gate came wrapped in plastic, it’s ubiquitous. Until we can’t afford it. A lovely article, Paul, I have many a fine field gate around here, and many a poor one too!

Rico

“nobody every talks about how many times something can actually be usefully recycled and what the lifespan of that future product is and where it ends up.” That is not true or correct. There is an analysis discipline called “life cycle analysis” that examines questions just like these. Some of these analyses include models of enormous portions of the industrial, chemical, mining, raw recovery, and recycling processes across the economy and does so in great detail. The work is done at various levels of fidelity depending upon available information and system boundary, but quite often they are based upon mass- and energy- balanced models. Within these analyses, people _do_ look at questions like, “how many times is item X reused,” “what is the disposal / recovery process,” and what are the various outputs to the environment for scenario A vs. scenario B. I am not taking a position on the particular question regarding plastics that has arisen here, but I disagree with “nobody ever talks about [this.]”

The beauty of the mundane!

Some of your guestimates of longevity seem a little low Paul. 20yrs ago I made 2 gates similar to the one you describe as crude. They were a necesity along with wire fencing when we got a dog. They were made quickly from tanalised 3 by 1 stainless screws and bolts. They have been well treated with preservetive (initially creosote, before it was banned). Apart from the odd crack in the pales near the top they are as good as new. I would hope that they will outlive me.

Thinking about making them reminds me of Pippa who ran around with a mouthful of screws whilst I was making them. Sadly she now lives on as part of a Ceanothus growing above her grave.

Thank you Paul. Sometimes we stop and recognise what is around us, sometimes we don’t…but it is always good to be reminded to take the time to look. As for the gate, a beautiful picture and reminder to take care of what another person has done.

Top notch stone work on the wall. Just about a lost art now, but my Brother in law did stone work for a life long career and I marvel at the quality of the process.

Here I am as a newcomer to woodworking, dedicated watcher of Paul Sellers on youtube (thank you so much for that by the way), pondering the design and replacement of the gate on my deck that has deteriorated into rusty screws and sagging “pressure treated” (I think they mean chemical infused) wood. Here I am pondering that and Mr. Sellers comes and drops the perfect post about gates from across an ocean.

We bought the 22 year old house recently, so maybe it was a 22 year old gate. It’s done in the “Classic American Deck” style of boredom and emptiness. Someone probably slapped it together in maybe an hour. I guess it was functional, or at least “to code”.

So I research a little about gates and joinery for gates. The previous was roughly a mitred box with vertical 1.5″ posts every few inches. Mortise+Tenon for those seems straight forward, but joinery on the mitred box seems a bit more tricky since the top needs to support some weight potentially. Would a normal mitre work? I found a mitred half lap joint that might work. Or was it a double rabbet? I digress… By most accounts, it sounds like you want to limit joinery seams exposed upwards, so that rain doesn’t get in as easily.

My joinery skills so far include a dovetailed angled-roof bird feeder of my own design, a wooden mallet, and and a few practice mortise & tenons. So what do I know about joinery for gates? Not much, but thanks to Paul, I’m thinking about it and thoughtfulness matters.

Tom

“There doesn’t seem to be any other practical alternative”

there are

– manual grass shears (where one has to bend down);

– idem but with a long handle;

– sickle;

– scythe;

– electric grass shears (working like a beard trimer but on a larger scale); (makita, bosch, ryobi and so on) also available with a long handle.

– …

Now, letting some part of your garden with long grass (at least in spring) is good for the biodiversity.

Google “nomowmay”

Naturally curved pieces of wood were used in wooden ships.

It is also interesting in traditional roof timber framing; it gives a little bit more shoulder space in the attic 😉

The worker who made gates in the past was most likely involved as a wheelwright. Most village carpenters were. Most of the timber needed to make carts and wagons is curved. But it does leave the question did they use a curved piece on a gate for artistic reasons or was it to make use of curved pieces that were surplus? We seem to be obsessed with rectangular timber but in the past many utilitarian objects were made with the timber as it was, following the grain. It was often easier to split it rather than saw it. You had to be pretty good to look at a tree and judge its future potential / value (and need) knowing that it might be 10 years before it was processed and seasoned.

The wheelwright was probably also making local furniture.

Like carts and wagons gates seem to have varied by location in the UK. Ditto the timbers used in buildings.

Some things in this comment prompted a deeper consideration: “The worker who made gates in the past was most likely involved as a wheelwright.” It’s possible as all things are possible but it is all too easy for statements like this to soon become fact in the minds of readers when in reality there would be many a thousand times more joiners and carpenters that made gates than wheelwrights. In any given city, town and village the number of joiners not referred to as wheelwrights and who never made a wheel in their lives made an inconcievable number of gates of every type by the millions. Any wheelwright worth his salt would be gainfully employed making wheels along with some carriage and wogon making and potentially gates too. I say this to caution how things might be conveyed. Certainly, carpentry companies would employ a variety of different woodworking trades under the company banner of Carpenters and Joiners and Cabinet Makers and Joiners and these companies might well at one time have had a wheelwright amongst those many woodworking trades but the carpenters and joiners would outnumber the wheelwrights by a thousand to one at the very least. It’s also true that within the various woodworking trades, the different craftsmen were highly protective of their specific craft and guarded crosscontamination of the trades hence the use of the term ‘trade secrets‘. The Guilds were also very active in protecting those completed apprenticeships and journeymanships who’s work was then qualified by peers in the guild approved in their very specific craft too.

Also, “We seem to be obsessed with rectangular timber”. With boat building and various wheeled carriages and wagons, continuous grain was indeed essential for strength. Whereas the forests of Britain were depleted greatly for warring ships, other boats and merchant ships to gain power and dominance on a world scale, the majority of wood had to be slabbed and squared into driable slabs and beams for subsequent air-drying to get the moisure levels for best control of the wood before most joinery and furniture could take place. This was by no means being “obsessed” but absolutely essential. How much more is that the need today? Lastly, “You had to be pretty good to look at a tree and judge its future potential / value” The formulae for wood conversion is a simple enough process where the first glance by an experienced harvesting supplier first gives a good guestimate as to the cubic footage or meterage but then simply confirms by girth and height measurements. For commercial supplies of timber over the past few centuries we have relied heavily on commercial methods of resawing with accounts apparently going back to ancient Rome and Egypt but some European countries in the 1300s. I think for the main part it has been a few centuries since we wedge-split tree stems into lesser components except in some very specialised cases.

Fair enough Paul, but I was trying to reason why curved timbers are used on gates, when to get the required triangulation a straight piece would be more logical. I was summarising from a book written about a wheelwright family business.

The author had become head of the firm (by his own admission old fashioned) before his dad had fully passed on his experience due to an early death. He described the business as wheelwrights, even though they many other items from wood, and metal after he added a blacksmith shop to saw buying in metal parts.

he commented about the difficulty of buying trees from local woods and hedgerows where he had to judge the output:

Local soil condition affecting the timber,

Any decay present,

Their future requirements in terms of curved pieces

Transportation costs

etc.

He did say that he didn’t always get it right and found it difficult, you couldn’t really apply a formula to it, it was more judged by eye from experience.

It was the above that made me think that curved pieces that were surplus might thus have found a use. Equally the use might have been down to local tradition.

Interestingly, going to grammer school, and not being apprenticed young, he does describe a feeling of inadequacy. For example has father had the role of top sawyer, but he preferred to be in the pit, leaving that role to others.

Other interesting things was he sadness at the amount of trees felled as a result of the war, especially that it was done at the wrong time of year.

The business was on a fairly busy road, so they got repair jobs from passing traffic, he commented upon how inferior “factory made” wheels were.

I guess it fascinated me as were I grew up their was a carpenter and blacksmiths shop, and as some farms still used horses and wooden wagons there was the where withall to make / repair wooden wheels, although hidden by weeds. The rullies used being more likely to more modern rubber tyres.

Many of the farms I knew in my youth used for example a suitably thick piece gleened from a hedgerow, rather than a man made stale in a broom. Equally I have seen gates repaired with a suitable branch rather than a man made product.

I remember someone commenting about someone collecting kindling from a hedgerow, why didn’t they just buy it from a shop. We seem to be deluded to believing that shop bought / processed is better.

Thanks Keith and Paul for such fascinating exchange

– There are people rebuilding old ships.

Google “rebuilding Tally Ho EP19” to see a guy selling and milling curved timber.

– for timber framing, perfectly straight untwisted and four squared beams are not absolutely necessary. Of course it takes extra skills (and time) to do the marking and joinery.

google “GUPEA the invisible tools of a timber framer”.

you will find an explanation of the methods used in various countries to cope with irregular timber.

Plenty of practical illustrated examples.

Interesting to see the live oak being milled. When I see such things it always makes me think that in the past such things were done soley by human and animal power.

Looking around at past achievements built by hand you sometimes have to be amazed at what they achieved. Be it ships, houses, castles, or even the various henges.

Never worked live oak, but I have worked very old English Oak, centuries rather than decades. That is really hard on tools.

Lovely to see another interested in old gates. They always catch my eye as well when walking the countryside. For my O Level centre piece I built a gate for our front garden to replace an old and rotting existing gate. The centre was a depiction of the Sun. Quarter circle in the bottom corner with radiating rays. With some vertical and horizontal bars. An awful lot of mortise and tendons. Always wonder how long that lasted. Chip chip

What is it about gates that we find so enamoring? At my last house, my favorite feature of the whole property what this little white gate that sat between two hedges, in the shade of an old apple tree, that led to a vegetable garden just beyond. One end of the hedge was only 10 or 15 feet away, so it was quite possible to walk around the hedge without using the gate, yet I found myself passing thru the gate often just to use the gate, to swing it open, and then latch it behind me. It’s been 20 years, and I still think about that gate, and wish I had need to use one on my current property.

Great post.

Paul, I have subscribed to your posts for years. I am guilty of not reading every one of them, but I do file them in safe keeping knowing that when I do take the time to read your posts I will have the pleasure of reading treasures of wisdom and great prose.

The first gate at first glance is so simple but when you notice the tops of the posts and then think more about the curved brace it feels almost delicate. I love it.

Your drawings of the gates makes me think of Eric Joliffe in Australia. He used to draw some of the old – usually abandoned – buildings that were built by the early settlers. He often caricatured the buildings and the people who might have lived in them, but still told their story.

The buildings were almost always leaning into (or was it away) from the wind and looked like they might not be there in a few years. But, they had a story and many memories. The drawings capture something a colour photo just misses.

The enthralling thing is the integrity of old school mentalities. Admittedly they arose partly out of tradition, partly out of the timbers readily available in localities, tools and prevailing technologies. But there was also the old school mindset, not the one of opportunists seeking to take advantage of people, but a genuineness sadly, virtually non existent today.

I have never forgotten the integrity of George Sturt, (George Bourne) in his incredible 1948 book, the “Wheelwrights Shop,” describing in incredible detail the intricacies of every aspect of making wooden cart wheels ( including the metal work in great detail), from the felling of trees to the drying and pit sawing of the timber through to the finished product with explanations of the purposes just like this article about garden gates. His book has been reprinted .

If ever anyone wants a real insight into old school craftsmanship, technology, and quiet consideration of the realities of the day, this book will be a delight to them.

“Windmills and Millwrighting,” by Stanley Freeze (1957), is a similar quality, describing in enormous detail, the intricacies of construction and operation of windmills.

Similarly “The Village Blacksmith,” (1971), by Ronald Webber is another outstanding record of the thoroughness of old school integrity and practice.

By contrast, the ‘philosopher and mechanic’ Matthew Crawford, in 2009, wrote and excellent book, “The Case For Working With Your Hands,” (“or why office work is bad for us and fixing things feels good”), delves into the mindset of making and mending.

Disciples and devotees of Paul Sellers will instantly understand and identify themselves with these men and recognise that Paul is genetically, philosophically and practically the same as these outstanding craftsmen who like Paul have selflessly shared, albeit in a much more limited way than Paul, their knowledge and experiences.

The future owes a great debt to these outstanding men.

P.S. (post script). George Sturts book, “The Wheelwrights Shop,” was FIRST written in 1923. Mine is the 1948 edition

I love the standard of having respect for the maker by treating the gate well. It rings so true with mankind as well. We all have a maker that made us thus, and we ought to treat our fellow man well at least out of respect for the Maker. When you harass someone or curse them, you’re not regarding their maker and the love he knit them together with.

Paul, in the first example, the mortise gate with the curved support, there is a 12″ rod at an angle set into the top of the end post of the fence. It has a ball on its end. I wonder what purpose there was for it being there. Looks like a little flagpole. Loved this article and the comments, Paul! And how I now know how to burnish my scrapers!

Ah, it’s a long lever that can be pulled towards the gate to disengage the latch from its keep. The long handle is so that someone on horseback can open the gate without dismounting, ride on through and let the gate fall to and latch itself by the weight of the gate.

Wheelwrights

It is a great mistake to romanticise peasant life and hardships and deprivations of “ the good old days,” but it also a mistake to minimise the needs and benefits of modern, semi skilled mass production and modern technologies. But to those of us that have discovered the joy and fulfilment of working with our hands and the pleasure of the use of “ essential wood working hand tools,” these quotes from George Sturts book, “The Wheelwrights Shop,” will express what we’ve discovered and will compliment the emphasis of Paul Seller’s beautiful obsession with hand woodworking as well as his comments on this post about “It’s Just A Gate:”

O6: ………true, the customary hours were from 5 in the morning to 8 at night

P9: Lofty souled though lowly minded labours

12: I felt that man’s only decent occupation was in handicraft. I shudder, yet smile, to think now what raw ideas swayed me then; yet the enthusiasm so ill reflected in them were the sweetness of life to me in every disillusionment that was to come.

I was glad to miss the “good mornings” of other wayfarers, not recognisable in the unlit street. I wanted to be alone, nay, so great was my passion for solitude that sometimes, if I had time and the weather allowed, I digressed into a lonelier though slightly longer route

16: it should be pointed out that in those days a man’s work, though more laborious to his muscles, was not nearly so exhausting yet tedious, as machinery “speeding up” have since made it for his mind and temper.

19: there was nothing for it but practice and experience…. What we had to do was to live up to the local wisdom of our kind; to follow the customs, and work to the measurements, which had been tested and corrected long before our time in every village workshop all across the country.

24: One aspect of the death of Old England and of the replacement of the more primitive nation by an ”organised” modern state was brought out forcibly and very disagreeably by the war against west Germany

24: ……but what would never be recovered, because in fact war had already found it dead, was the earlier English understanding of timber, the local knowledge of it, the patriarchal traditions of handling it. Of old, there had been a close relationship between tree clad country side and the English that dwelt there.

24: A greedy prostitution desecrated the ancient woods. All around me I saw and heard of things being done with a light heart, that had always seemed wicked to me…… Not as waste only was it hateful, it was an outrage on the wisdom of our forefathers, a wanton insult put upon Old England in her woods and forests.

25: ……….. for his quest took him into sunny woodland solitudes, amongst unusual things and with countrymen of a shy type, good to meet.

26: Another matter the wheelwright buyer had to know was the type of soil that the timber grew on.

28: (Of carters), These men, old acquaintances from a near village, had rustic talk and anecdotes, rustic manners. I never saw them other than quietly wise. To watch them at work, unhurried, understanding one another and seeing with keen glancing eyes what to do, was to watch, (unawares, and that is best), the traditional behaviour of a whole country side of strong, good tempered Englishmen.

49: …….then one’s eyes were unsealed to meanings of grain and texture only reached by actual working with timber

53: I would have been bankrupt in business in 1884 if the public temper then had been like it is now, grasping, hustling, competitive, but then, no competitor seems to have tried to hurt me.

54: I never could get the axe or plane or chisel sharp enough to satisfy him, (a man called George Cook). But I never doubted then or since that his tiresome fastidiousness over tools and handiwork sprang from a knowledge as valid as any artists. He knew, not by theory, but more delicately, in his eyes and fingers.

54: So, unawares, they lived as integral parts in the rural community of the English. Overworked, underpaid, they non the less enjoyed life, I am sure. They were friends, as only a craftsman could be, with timber and iron. The grain of the wood told secrets to them.

55: My father had been habitually considerate

56: George Cook was a terror in this respect. Time seemed no object with him, he must get his edge.

59: …….. after those parched hours I have always felt that there WERE excuses for the notorious drunkenness of sawyers, who had not hours but years of this drudgery to endure.

65: …….. no sentiment governed it, no commercial greed affected it much. The spirit was simply utilitarian………… it was rather a long business, but in country places that didn’t matter so much as getting the job done effectively. This was still the governing idea in that seemingly far off time.

79: As is often the fate of stingy men, he was over reaching himself.

80: Different trees from different soils varied considerably in their weight and due allowance must be made for such variations.

91: Bookish training was too feeble to enter into these final secrets; evidently there was something more, only revealed to skilled hands and eyes after years of experiment.

100: These men, I knew, would sooner be discharged than work badly, against their own conscience.

108: (of George Cook), his attitude was that of a very efficient, if very unsophisticated provincial, keeping close to the materials of his own neighbourhood, and in touch with the personal crafts of his own people….. I think his idea was to slip through life effective and inconspicuous, like a sharp edged tool through hard wood.

112: Where a city dweller would be helpless, this family profited by centuries of tradition, and they were keeping old England going, (“old” England, not modern England), when they made elderberry wine and warmed some of it up for a friend on a cold winter night.

198: We knew nothing, thought nothing, of how much we ought to have, but it was very needful to know how much our customer would pay…… neighbours with little or no competition, would find out the fair prices of things and not dream of departing from them.

Something like the first gate could make an interesting project for Common Woodworking. I would be very interested in Paul’s judgement on all joinery!

Post his accident, I suspect that making a gate would be a bit much to expect from Paul presently.

However, his drawing tells you most of which you need to know, although the dimensions are a bit obscured. The skills needed for timber preparation, joint making etc are all on the site, It is simply a matter of applying the skills. The only bit that isn’t clear is how the curved brace is let into the top rail, if its a simple lap joint or if as I would prefer to do morticed in. I suspect that biggest challenge might be obtaining good suitable timber. When I first saw it I did consider making a scale model of it.