Planes Away

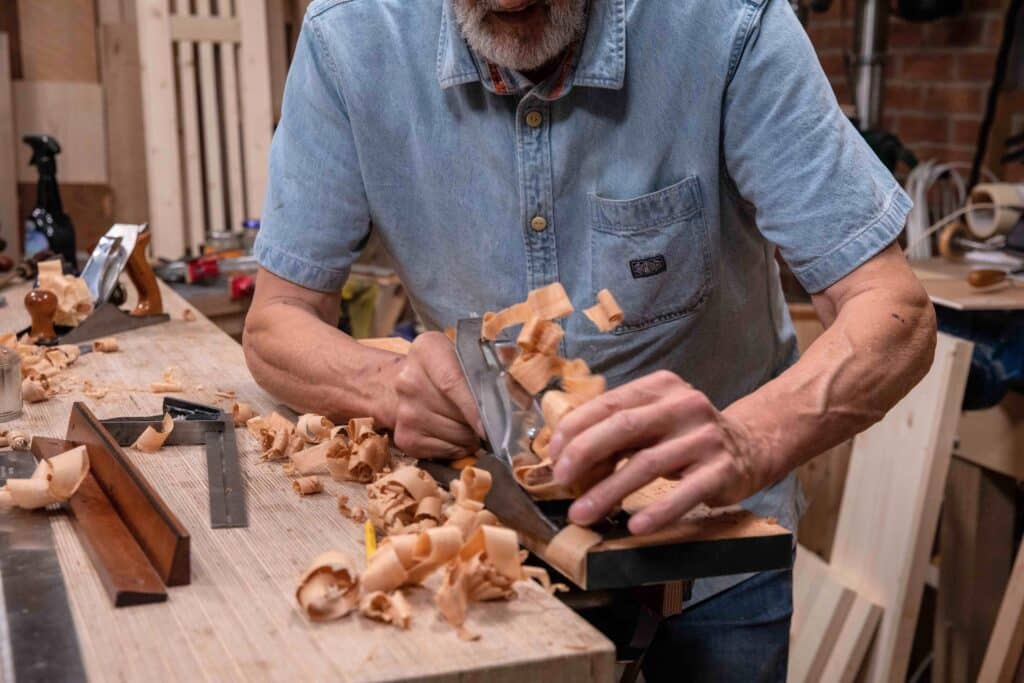

I have written quite substantially about the advantages of owning and using different bench planes. Bench planes are the most significant group of planes we use in our everyday bench work. It’s that wonderful category of a handful of bevel-down planes we hand tool woodworkers rely on for all our general straightening, levelling and otherwise the initial truing of our wood. Additionally, we use the smoothing and jack planes for all our trimming and fitting wood into wood––frames and drawers into openings, removing swollen stiles to fit again and more in the making of all wooden projects.

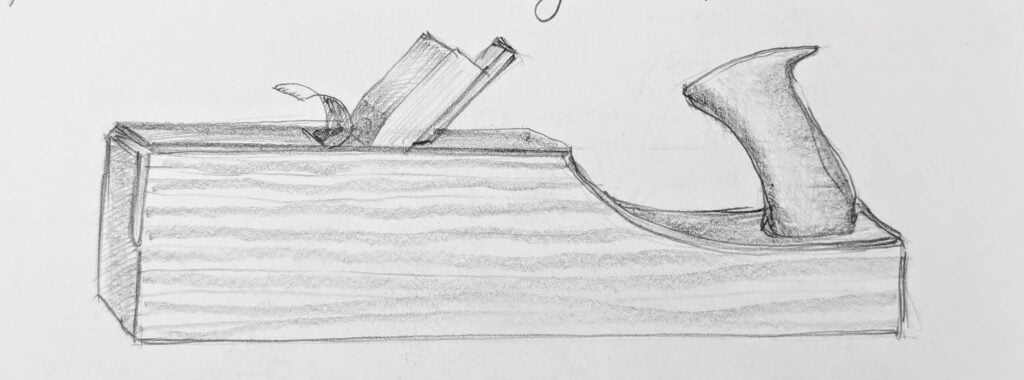

It is more than interesting that in mainland Europe, the makers and users there continued using their preferred wooden planes for bench work. Even in the last seventy years, the all-metal versions have been slow to gather very much ground and that’s because all metal planes have twice and three times the level of friction on the wood that wood on wood does. Over the longest period, European woodworkers making for a living continued for a century beyond the invention of the cast, all-metal versions and never really transitioned through to fully or even partially adopt the cast-metal options as standard equipment. Not so in the US and British realms. But there was good reason not to. We tend to think that cast metal planes will be the more advanced method of woodworking which is far from true. Look at some wooden planes, perhaps the top one I am using, and then a dozen others that I use, and I doubt that they were used for less than fifty years of daily and continuous use.

Mostly, in my view, it will be what you are first introduced to and what you get started on in your starting-out days that will more likely determine what you continue to use in your woodworking. The truth is this; wooden planes are much lighter on the wood and the secret here is “on the wood“. No matter how heavy wooden planes are in the hand, and they are not particularly heavy, as soon as you place them to the wood and push they will always glide weightlessly across the surface as if by some magic and all friction has been removed.

Ultimately, you start to add others to your collection as you grow. Usually, this happens through some ad-hoc venture past a garage sale or flea market. There they are, to be picked up and often for pennies: bargains abandoned by the children of former owners wanting to be rid of “old junk”, parental “clutter” and “junk”. By this adoption we discover, and usually for good reasons, that every plane type is uniquely different, with one being more effective in this work type over another. I find I do have preferences but not because of the maker name as such but more for the tasks they seem more aptly able to perform and the way they work as such. Sometimes, and I can’t always altogether explain the reason in the moment, I quickly switch over to reach for another plane that I might not have touched in a month and I am usually very glad I did. This quick change from one usually makes all the difference.

I have bench planes conveniently housed in a carrier at the right end of my bench well. It’s inclined and when my hand slides into a tote the plane comes effortlessly to work in a split second. Three planes sit there, my #4 smoother, my #4 scrub plane and my #5 Jack plane. They come out sequentially according to need. Behind me, on my support table, I have other planes including a second regular #4, a #4 1/2 and a #5 1/2. These too get regular use.

At the end of my bench to my right, I have a couple of wooden planes to use when I want them. Of course, I am talking about bench planes and not the other planes I rely on. One extraordinary plane that doesn’t fit the bench plane category but gets used as one is my converted #78 which I adapted to use as a permanent scrub plane. It might seem a crude-looking tool but boy does it work for the rapid reduction of excess material in a wide range of work issues ranging from panel raising to chamfering, scrub planing and so much more.

For me, now, no plane ever made will replace my #4s in Record, Stanley and Woden makes. These are the workhorses I do everything and anything I want to do with them, as much as any other bench plane ever made––possibly much more. By the time I concluded my apprenticeship in the 1960s wooden planes were all but gone in Britain but it was not because they didn’t work and work exceptionally well. Though wooden planes were still plentiful, replacing them at a cost-effective price for retail became much more difficult because demand was much, much less. Industrial machining in every realm of woodworking including amateur shops rendered them obsolete. Who on earth with any sense would want to hand plane and hand saw their wood using primitive methods like that? And power sanding the machine textures left in the wood just got better, easier and more predictable. Switching out a disc or a belt in split seconds took you from 80-grit, deep sanding to 350-grit, silky smoothness in a few consecutive passes. Why plane?

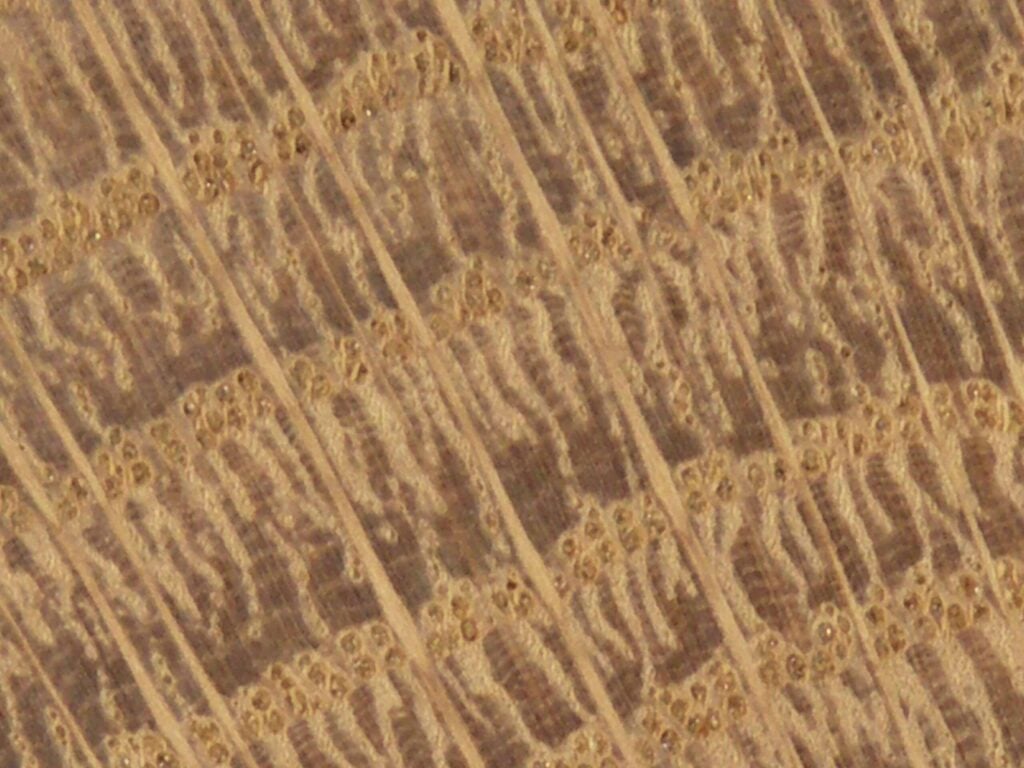

I think that that should be considered. Sanding changes the texture of the surface of the wood. Whereas both feel supremely smooth, a sanded surface lacks the crispness you get from a planed one if and when the plane iron was sharpened to 10,000 grit. The difference defies words. The sanded edges inevitably round the corners as by its very nature, abrading inevitably abrades everything in its path to the degree of unevenness the particulate size and type determines. The planed edge always has a crispness to it you cannot get by sanding with abrasive discs and belts although there are tricks to get that even from a random-orbit sander. But, too, the precision of hand planing is remarkable. Taking off an even thou’-of-an-inch or millimetre is well within reach in the hands of an experienced craftsman.

The investment the inventor and developer Leonard Bailey, together with the Stanley Rule and Level Co, made into the development of their bench plane series of eight-plus bench plane lengths was so good no other plane maker then or since came close to bettering the mechanical functionality and quality of the Bailey-pattern plane. It was so good that any other makers of Leonard Bailey’s work could only offer knock-off copies. In the details, they never really offered anything that improved the plane even though they boasted and still boast to that end. Rather than inventing anything to change the dynamism of the plane, they merely offered tighter tolerances that actually encumbered the plane as such engineering often does. Think sloppy gearsticks of a well-worn 1960s Morris Minor, how you slipped the gearstick from second to third half a minute before it engaged and how well that worked for those of us who knew it. I can use the #4 plain-Jane plane version for making raised panels and scrub planing over and above general trimming, refining and truing the wood they are confidently known for. It’s a strange assumption that somehow saw the transition of buyers buying all-metal versions they rejected throughout the 20th century. Someone, somehow pursuaded them that expensive versions would suddenly bridge the gap to translate them from unskilled outcomes to skilled ones––that the tools they were using, those unsophisticated primitive ones, were the real problem and nothing to do with any lack of skill––buy a tool ready to go straight from the box and all skills would magic their way into their lives. But no one told them that bench planes would be high-demand tools and high-demand for the rest of their lives because every time you sharpen them you must remove and install different components every time and that this can happen ten or even more times in a day if you are using a plane throughout the day. Sharpening and setting are maintenance tasks and you cannot have one without the other. 99% of good planing outcomes revolve around the sharpness and set of the plane. Once you see that and accept the reality of it you are on your way to good planing practice with pretty much guaranteed outcomes every time you use it. Of course, we believe that better-engineered tools in iron will automatically be better than vintage versions and it makes sense to think that way even if the reality is the opposite. It is unlikely that any modern user of all metal planes would or could ever match the quality of work the wooden plane users accomplished. It’s not that they can’t. I don’t believe that. there are many reasons that they never will, not the least of which quite simply is the loss of skills. I believe that there are makers who could achieve the same results but that they would more than likely take ten times longer to do so.

When I read someone saying, “You get better control and weight to achieve a higher degree of control using heavy metal planes.” I tend to think more ‘bull-in-a-china-shop’ than a refiner of fine work. Most often there will be a sale behind such words. When the selling dynamic hovers in the background I find the informant less trustworthy. My thoughts on that are the same as to those driving massive, single occupancy four-by-four so-called SUVs as city slickers where image and privilege are everything but the road-hogging consequences mean nothing. A heavy plane usually relies on mass and muscle to push things through and for short bursts of work they are fine but using a plane as much as I do it just doesn’t work. Add to that the friction of weight and body mass to the sole surface and it will indeed take much muscle mass to muscle through for a result. In 60 years of daily, full-time all-day woodworking five and six days a week I have been able to do all my planing work with two quite basic #4 and a #5 planes.

I often read and hear the term, “My go-to. . . this or that is this or that.” And whereas we Brits use 10 words to the American one, there is a difference between choosing one plane over another that minimalist terminology never quite captures. My ‘Go-To’ tools are rarely to the exclusion of others in the same way I choose a collection of words for a sentence that aptly describes what I prefer and do rather than copycat others. In recent video episodes we made I chose wooden Jack planes to level and true my oak for the two projects in oak drawers. I felt these planes, though perhaps even slightly weightier to lift to task, suddenly change on the wood to float like a dream and feel even less than half the weight of any regular Stanley #5 as they engage the wood. What saddens me is this. Less than the smallest fraction of a per cent of woodworkers will ever experience a well-set and sharpened wooden plane just to understand what I am saying.

There is no doubt that Asian and European woodworkers retained what worked exceptionally well for them and even, dare I say it, worked even more efficiently than any all-metal version. I liken this outcome to the probability that machining wood became more acceptable to competitive business owners than using primitive hand tools. We see a direct correlation between advancing industrialism and the demise of handwork and hand tools on every continent and the destructive forces of industrialisation overwhelmed all crafts. But I think that it is important to understand that industrialising life is negative progress for the majority who became merely owned by the industrial wealthy and had to give in to the demands imposed on them through the possibility and probability of becoming impoverished if they didn’t accept what they called “progress”. For it wasn’t that hand tools didn’t work and work well, it was that they didn’t keep pace with industrialism, consumerism and the demand for the ever-unfolding ever-changing entity now called ‘the economy’. No longer the simpler life of self-sufficiency and sustainability. The demands surrounding ever-cheaper goods forced everyone to not only become a part of the mechanism, they had to somehow embrace it. Of the dangling of consumerist carrots, there is no end. And then for engineers to remain in business there is no point inventing new stuff when you can simply copy what was already designed and invested in by others a century or more earlier. That is what we mostly do after all. And if we can convince our audience that we’ve engineered out the flaws of earlier models to present something better then we eliminate the need for research and development. All we need is the better mousetrap, right? Well, not quite? Just as no metal plane ever bettered the wooden one, no heavy metal planes bettered the lighter-weight ones either. Such facts as these will eventually be lost in the belief that the vintage models were abandoned because they were indeed believed tobe bettered because, well, we have to be evolving into something ever-better.

When you do as much hand work as I do in any given day you also look for economical use of your body and the tools you use. You want a direct correlation between the waste you remove and the time it takes to maintain a functional tool like a plane that needs immediate and responsive adjustment minute by minute. Clunky heavyweights cannot give you that so it is an evolving process that led to the evolution of the Stanley Bailey-pattern plane that cut the excesses of heavy bodies and thick cutting irons in the wooden British planes and went for ease of sharpening and functionality on the job. You have watched me making thousands of videos and hundreds of pieces of furniture in hardwoods and softwoods. Name one of them, or posts on my blogs, when or where you have seen me reach for a heavyweight plane to tame any aspect of my woodworking. Why haven’t I? I simply do what works and works best. But more than that, those following want to know the simplest ways that woodworking works. I keep things practical and simple.

If I only had access to the above planes to flatten boards for a tabletop or true-up four-by-fours for table legs my so-said “Go-to” (and that’s the last time I will ever use this lower-grade term) plane would not be among them. If this was what was offered and I had to choose one for the task, it would be the wooden top version even though I do enjoy owning the other types. The ratio of use might be ten to one for the wooden one and then equally for the other two but you’ll get substantially greater success on planing flat wood with the Bailey-pattern bevel-down bench plane than you will with the Veritas simply because low-angle bevel-ups fair less well and tend to tear the grain wherever you get rising grain in opposition to the planing direction. So, the first choice is the wooden version, the second the Woden and the third the Veritas, but remember I am talking about general planing of face grain here.

You adjust yourself to enjoy the different characteristics of various bench planes. The question for me ultimately revolves around ease of use and that’s because I use them so much more than most other users. The plainest version of the original Stanley #4 smoothing plane is a perfect design for an all-metal plane and no modern plane maker has improved its functionality in any way and may well have impaired its performance with over-engineered intolerances. How about that!

Some woodworkers new to the craft will find the British wooden ‘block’ of a plane cumbersome and awkward to manage balance-wise at first but you soon get used to managing it if you persevere and give it a fair chance.

The razee versions are rarer and this type lowers the rear tote for a more direct centre-of-thrust nearer to the catch-point and follow-up thrusting of the plane-stroke cutting edge into the wood. I am always curious as to why plane owners didn’t lower the latter third of their regular planes like this because it makes a big difference. I have seen a few theories as to the term ‘razee‘ used but prefer the etymological version meaning to reduce or scrape lower, usually by abrasion.

Thanks Paul. Wonderful post with much to digest.

I have some wooden planes and really enjoy them when I use them. What I haven’t fully understood is why aren’t the so called “transitional” planes more popular. Wooden sole and the controls like a metallic. To me it seems the best of both worlds.

As for heavier weight planes, I can think of literally only one time in the 8 or 9 years of woodworking where a heavier plane actually helped. I was planing some ash and having a heck of a time keeping the plane in the cut. I tried all manner of hand planes but it was a heavy premium No 8 that worked best. Literally, that is the only time the extra weight helped. I regret that I purchased that No 8 given how infrequently I really use it. I wouldn’t purchase it again. I thought I would use it a lot more when I bought it. I wish I had paid a bit more attention to you those first 6 months when I was tool shopping. World won’t end.

Ah, I have an answer for your #8 so don’t ditch it just now and we’ll get to is shortly: you’ll love this one.

Thanks Paul. Looking forward to that post.

I was about to ask the same thing about transtional planes , but you phrased it better than I could

Could someone please let me know Which is the project where the wooden planes are used? Thanks!

I really like my 78 scrub plane, but I after filing the mouth a tiny bit it is fantastic. Another of your ideas that was too good to be true.

I have a #6 Stanley plane the I might have used once. It’s just to big and heavy for me and I’m not sure where it might come in handy for what I make. I’m curious to find out where these large planes might be useful.

Personally, my view is that the equivalent in wood and with wood on wood they move efficiently over the surfaces of wood in truing. The metal equivalents were just to heavy but the engineering of things often only have purpose in the heads of engineers who get job security from inventing the as yet unknown problem and societal need first and then provided the supposed solution: A bit like the internet. These monster planes in all metal construction were never used in reality. I’m surprised they didn’t make solid cast iron handles to increase the weight gain and then a pulley system to hook up to the wall to pull the plane forward and backward. The upturned long planes were commonly used to true barrel staves.

I have a Stanley No. 6 that I use for shooting (that’s where the weight helps) and as a short jointer when a 7 or 8 would be overkill. It’s a type 13 and is really a joy to use. I love all the Stanley planes but that 6 and my type 9 No. 4 are my favorites. Good luck!!

I was recently given a Record No6 from a friend who’s woodworking father had recently died.

It’s big and heavier than my Stanley No3 and No4 but it’s a joy to use and feels really balanced.

It’s so easy to use but that could be because the lifetime craftsman who owned it kept all his tools on best condition.

Thanks Paul – my grandfather left us two wooden block planes that are sitting in my shop… waiting to your words… I will try and do my best to put them back to work. he learned the trade in France in the early 1900s but in the 80’s he still wanted to make new wooden block planes for his last jobs… there is a very old one still there, who knows how old … but your post took me back to what I have in my blood… some wood dust, thanks for your contribution, amazing

There once was a joiner named Ted

Who scratched his head till it bled

But wasn’t red blood that came out as it should

But sap mixed with splinters instead

I am Groot

Paul I’d love to see a blog or video from you explaining what to look for in buying a used wooden plane. Whilst it may push the price up(!), I feel I wouldn’t really know what I’m looking for at present.

Unless you’ve already done so before and can kindly point us in the right direction? I’ve consumed most of your content but don’t recall this.

Paul does have some older YouTube videos on restoring/cleaning up a wooden plane. Been quite a while since I watched them but it might answer some of your questions.

I have used mostly bailey Stanley planes for bench planes and although I have wooden bench planes acquired in the last 15 years have not used them much. My most used plane is a Stanley 4. Next used are a Stanley low angle block plane and a 5.

I have learned a lot from your book and these Blogs and appreciate that you provide all this interesting and useful information. Thank you.

I have to respectably disagree about a number six not being useful at all. I had one and ended up with two of them as the second one came with a group buy and was considering selling it off. But a recent potting bench built utilizing some salvaged 4×6’s ripped in half for the posts they where quite handy for getting wood to dimension, one with more camber and one with less. And quite frankly I like the work out and efficiency of them. But that is just me, at 74 I can still sling them around and am great full for that. Now back to the flowers.

Hi Paul,

Many years ago my brother was just starting his apprenticeship and was starting his collection of tools. My inlaws moved house, the prvious owner was a carpenter and in the garage, which he used as a workshop, were 4 wooden planes, all in working order, no worm! I told my brother, but before he could get round to see them, she had destroyed them, she had used them to raise the tipping front seats in the car!!

I inherited a Stanley #4 which, using Paul’s videos I’m getting a reasonable tune out of. I needed a longer plane though but wasn’t willing to pay for a #5 or #5 1/2 or longer so I took a chance on a wooden plane from eBay for about £5.

It is excellent to use once you get to grips with the hammer tap adjustment (emphasis on “tap” with a very light hammer) and if you wipe the sole with the rag-in-can oiler there will be almost no friction at all and it goes over a board so smoothly and fast that you actually need to hold it back a bit to stop it just shooting right off the end (and almost through the window of my small shed!)

This post and your video on how a plane automatically produces a shaving without any downward pressure needs to be paired. That’s pretty much all you need to know about planes.

Yeah! All these gurus crawling out of the woodwork these days saying you need to bear down on the wood from above so your body is over the work instead of saying you need to sharpen your plane right now and stop procrastinating if you must do that to get a shaving!!!

I made a Krenov style wooden plane a couple years ago. Making it was as enjoyable as using it. Your post makes me want to make another one. It’s a great way to use up some extra wood (I hate to call it scrap) that is a bit too short for most projects.

Hi Paul,

I am very interested In your reply to Joe in the first comment on this blog post about his #8. Hope you post your response on another blog here. I have a #7 that I have used in various ways over the years and would not ever consider letting it go.

Thank You, …. John Parker

I am 60 years old, when I started wood working dad gave me a old wood smoothing plane I was 8 years old. it was worn out, uneven sole and wide mouth due to the wear. I used it like a scrub plane.

Eventually it was not used and left on a selve gathering dust and cobwebs. After many years I restoed it fitting a new wood sole and tighten the mouth. I gave it back to dad on his 80th birthday. he used it on and off for 5 years. It’s now mine again and my favourite smoothing plane.

Well done Mark. Your post made me smile. 🙂 Perhaps there is hope for mankind after all?!

Regarding the so called big planes, I have used a #7 to great effect making masts for small boats. The thing just moved along with not much effort and created marvellous long ribbons of spruce. So, I don’t use it on small timbers, that is for the #4 and a delightful #3. Horses for courses. Big plane for the big jobs. Small planes for the small jobs. Simple.

Really disagree with this, Roger, and not just a matter of opinion either. Perhaps more to do with a man’s preference. Not many will be making spruce masts for one thing. Hazarding a guess I would say one in a million.. And I never use anything bigger or should I say longer nor have I than a #5 and that’s in my sixty years of daily woodworking and furniture making. Simple.

I guess my point was that a well sharpened #7 will work with surprisingly little effort on what it was designed for, long straight timbers. Its weight did the work, all I did was push it along. As I said I would not use it for furniture. Most of my planes were given to me, including a #4 1/2 which I find too heavy, where a #4 the magic number, which I use as a really good plane for nearly everything. As you say a #5 is as long as I go for general work but the #4 can do just about everything. I also have a heap of wooden planes given to me and they work really well. Would I recommend a #7 for a beginner? No way. A #4 or maybe a #3 for a child and a spokeshave (151) which is what a dear friend showed me to get me going.

I prefer to use a plane that is a little larger also. I have some small and some large. The larger planes give me a little bit better control. It’s just my opinion and there is nothing wrong with using a #4 for all your work. My advice – just go do some work in the shop and enjoy using what feels the best in your hands.

A #7 is not just a little larger, it’s massively so. I try to imagine a sixteen years old starting out with the #7 suggested or to buy that as their start-up first plane. And then the other 25% of the world’s popu;ation of much slighter build, weight and strength in the lifting and placing of these brutish weight planes. Further more, of course, not everyone can just go out and buy long planes to have just as an aside. Best to deliver what’s really needed which is sound advice and to do it sensitively I think. A #4 will suit everyone and then a #5 to follow. No need for anything longer. Not for furniture making and general woodworking. You can always go the extra width if you are big boned and stronger so after starting with the #4 and building up strength and confidence, consider a #4 1/2 and so too the #5 1/2. But that advice is for down the road a ways. maybe after a year. These are my advice to all woodworkers and come from my concerns and considerations for those starting out.

Hi Paul, just saw this after my reply above. I think we are in violent agreement as they say!

Cheers

Roger P

Hello Paul. I have read many times that a #4-1/2, like the 5-1/2, was a wider sole “school” plane. When would you reach for either of those two over the #4 or #5.

Erroneous information, Lynn. All the ‘ancient’ men I worked with in 1965 had both sizes of planes in both plane types, i.e., #4, #4 1/2 and #5 and #5 1/2. They used them interchangeably throughout the day all day just as I do. The ones I witnessed looked just as old or older than the men I worked under, many of whom were in their 50-60s. I think it is unfortunate that many writers of woodworking articles and books have opinions that do not fit the reality of the day. When I sharpen my planes I sharpen six of them because generally I use six of them throughout the day. I have all of the ones mentioned above plus two converted planes I use all the time as scrub planes for removing heavier amounts of stock. I use Stanley #78 with a curved iron for heavy removal when I have a lot to take off or the wood is roughsawn, I then, usually, follow on with another converted or adapted #4 which I have also created with a shallower sweep to the cutting iron but still quite distinctively arched again as a secondary scrub plane. This strategy saves me many hours planing work in a week. I then bring in the other planes. The wider #4 1/2 is good for wider surfaces say over 3″ as is the #5 1/2 but the longer planes are the only ones I use for straightening lengths and edges. For instance, even though I do own a #6, #7, and #8, I would never reach for one and never have. I don’t even give them workshop room. A #5 and #6 will get me true in every case and have never once failed me or caused me to think longer plane.