I’m On the Plane . . .

. . . in fact, by the time you read this, I will have landed the day before, picked up Rosie and be in the workshop working as it will be Tuesday morning, the day after my arrival back in the UK. Portugal has been a welcome break in the sunshine an hour’s drive from Lisbon in the small town of Evora. I have always wanted to visit Portugal so this was my first touchdown there for a short visit. I will return to this lovely place when I can.

Culture is the ever-changing dynamic that perpetually shifts and shapes and reshapes any existing status quo as it unites the past to its present and then all that takes place in the split-second take-up of future performance and all that develops. Culture defines every element of the life related to who and what we are and even a brief visit of a few days, as mine has just been, here in Portugal, will reshape something of your life depending much on what you allow but then too all that you don’t allow and can do nothing about. The first part to impact me from my visit happened in the first few minutes passengering in an Uber from Lisbon to Evora. It was not the heat of the day nor the blue expanse above the highway, nor was it driving in a left-hand drive car on the opposite side of the road. I am quite used to each one of these from my long life living and working in Texas where we had all of these elements rolled out in the same way.

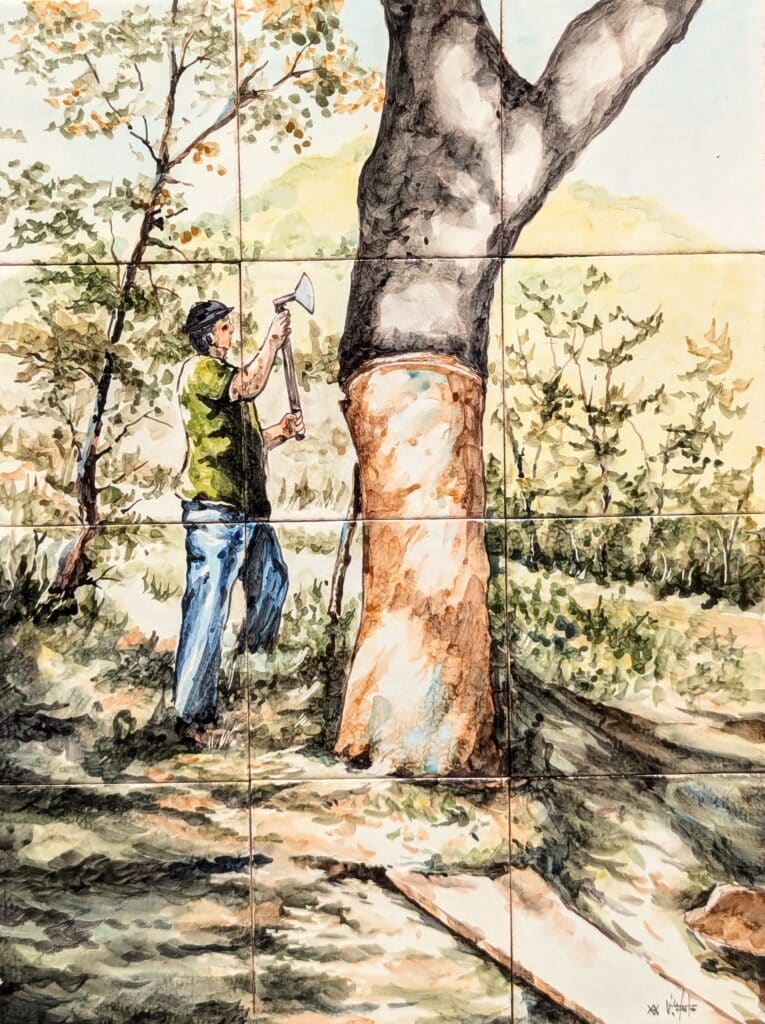

What impacted me was seeing oak forests where the bark was stripped from the stem up to and sometimes above two-thirds up but still holding a full canopy of green showing all trees to be fully alive and thriving despite appearances. You see, Portuguese oaks are a little bit the more unique. These oaks (Quercus suber), are the best trees to make bottle corks from and Portugal is well-famed as the predominant supplier of cork to the wine-making world. Most corks in the world come from these unique oak trees, which are highly protected and regulated to ensure the long-term sustainability of the trees and by that, the supply of wine corks for corking wine bottles. How amazing is that? Imagine a whole, sustainable culture surrounding corks for wine bottling. But cork has a wide range of applications yet the tree just keeps producing and keeps a steady balance between supply and demand simply because the people care for their trees in a proper manner.

I return to the opening words about culture ultimately defining all things about us. I never regard myself as a tourist. I’m here in Portugal to meet my family. When your family is distributed more globally it takes effort to get everyone together. Two years ago it was Austria, before that Berlin, Rheims in France (the unofficial capital of the Champagne wine-growing region where many of the champagne houses are headquartered.) Walking the streets and seeing the ordinary things made of wood and fastened to stone with steel pins is what I do all the time no matter where I am in the world. I look for what ties me to others in my life of woodworking and that often if not mainly includes those who came weeks, months, years, decades and centuries before me.

Over a millennia ago the Romans built the temple to the goddess Diana in Evora. Now whether it was the Romans that actually did the work or that they took the credit for work they demanded others to do I don’t know. Without wood, there’s a coldness to it so the trees around soften the harshness and harness me in my searches. Shoulderlines and carved medallions are a common thread with some quite rugged joinery still holding on but barely.

It’s been decades since I started my de-industrial revolution to reverse some of the damage done to my craft. In the beginning, it was indeed slow going but I persevered against the big boys and I came through to the point I am at today. back then I realised that with three joints and ten hand tools, you could pretty well make anything from wood. Wherever I travel my theory of that time seems to be pretty well proven. The dovetail joint, housing dado joint and the mortise and tenon have survived for millennia and that to me seems quite, quite remarkable.

I look for a form of a dovetail joint or the way an ancient tabletop was anchored by a dovetailed spline also held with dowels. How was it levelled and smoothed so crudely but crudely was the outcome of the work and yet somehow it also felt refined. A Trip Advisor sticker isolates its paired eyes to show me the new message in a pair of not-so-old wooden doors in the 15th-century convent where I am staying, though it’s now culturally changed into a comfortable hotel.

I often spend hours on forensic searches and stand staring at an ordinary door rail connected in some way to the door stile until I have absorbed all the hitherto hidden information I need to know the inside details. Shrinkage tells me a lot. A split in a rail might reveal dowels which fix points in stiles and disallow shrinkage in the rails until something gives and becomes a split. These overlaid door panels below display nothing of antiquity but more of our quick-fix, get-it-done-yesterday modernity where rotting parts arrived over decades of neglect and were then covered over with panels that quickly and readily hid the inner deterioration. A quick fix might look good enough to a property owner for five years and as craftmanship has deteriorated through the post-war decades and wages for crafting artisans have increased, this type of repair is evidenced in many cultures on a worldwide scale. Replacing doors for €2,000 plus some even in pine is less amenable than six routed softwood panels, a packet of nails and three hours work. All of Europe faces this kind of decaying construction because restoration, repair, replacement and maintenance were not factored into long-term planning and so are often the neglected cousins of property management and ownership. Rarely are such things budgeted for over the long term because of short-term planning and self-protecting long-term administrators with short-sighted considerations.

Something inside of me wants to remake the doors. Disrepair on such a scale is quite dispiriting and of course, business owners renting a shop and then even the owners too do not want to swallow up what they are in business for the most, making money. I can’t take on so great an undertaking but looking at how many woodworkers following me are looking for woodworking to do I could see how a town like Evora (or many others) could organise themselves into guilds to take projects as a means of preserving the inheritance itself as a major part of our culture but then too the training of new woodworkers. Taking on projects perhaps less grand than the spire of Notre Dame Cathedral might seem less worthy but in my world of crat restoration, recognition, craft conservations and much more, it would more than likely be far more monumental. Imagine a central workshop, fully funded and provided for by a town as a centre taking care of repairs to buildings. I know I am not the only one feeling this way. Imagine organising an assembly of skilled and semi-skilled woodworkers into a cohesive work crew and taking on requests at cost and not for profit.

Vintage furniture from a primitive period is not really what we see in the homes of the lofty and privileged. The majority of us don’t live in manorial homes and palaces and neither would we want to either. Most of us try and strive to live for realness although I do understand that the influences of the wealthy and privileged are always using unspoken words to say, ‘Look at me!’ ‘You can buy clothes like mine!’ ‘You can be a famous person kicking a ball around too, or a cook or a lottery winner!’ Of course, it’s mostly about improving their income as influencers. The richer and more famous ones now rely as much on sponsorship as the skill or ability that got the recognition. A bit different then than the glorified deity bestowed on Diana in millennia past for the goddess Diana, I suppose.

Anyway, back in the land of the real, I am recognising the impact of the Roman Empire’s spread as I visit both Paris and Evora and seeing Roman ogees and astragals coming off the ever-more ubiquitous power routers to bring moulding with tell-tale forensic evidence saying this is not that and that is not this. Keeping ourselves real costs us. We’re not looking for substitutes for skilled work and working or an easy day in an easy way.

Traveling to Evora I saw oak trees by the many thousands stripped part way from the ground on up and realised without reading or prompting by words that I was looking at a culture that made most of the corks used in bottling wines in the world. The Quercus suber oak figures extremely highly in the Portuguese economy and culturally this tree is rightly revered by the people of Portugal because it reliably keeps the wines of the world safe and has done so for centuries.

I visited a small museum hosting the design and culture of Evora. The artwork interested me yet again and I found several sculptures and other products made from the cork.

On the last day of my travels, I visited a winery and did not know I would fall into the thrall of a new winemaker establishing his own vineyard but amongst a team of support makers on an exploration into the past. Expect the unexpected is a great motto when you visit another country and this one has a past that is steeped in winemaking’s hidden gems. The wine is something many people are interested in and I understand the fascination. For me, it is both the process of changing fruit into wine but always important are the people crafting anything that develops a process built on the work of others. The man behind Fitapreta Vinhos is Antonio Macanita. His pathway of discovery, of course, follows his interest in wine but, as it is with any mystery, his path began by stripping away the veils and mysteries of those passing through in life who in one way or another covered up the history with layers of shifting culture by trial and error experiments, modernisations, with only a minimal sense of conservation, preservation or sustainability. I suspect, reading between the lines yet without knowing the man, Antonio Macanita the future at this winery will be quite an uncovering of the past’s culture and joining it, not necessarily seamlessly, with a new and exciting future.

Thanks Paul. Wonderful post. I love it when I see stories of how we live more in harmony with nature and the cork trees (as I had called them, didn’t know they were species of oak – thanks). I had read many years ago, ancient Greece had protections on olive trees for similar reasons.

I was thinking about what you are doing in terms of advocating for the use of hand tools. The good news is that every few decades it seems as if there a push by humans for more humanity in how things are done. I’ve not researched it formally but I can think of craftsman style furniture in the 1920s (guessing on exact decade), back to the earth movement in the 1960’s/70s, and locovor (eat locally) movement in 2010s. I think there is something inherent in us to want to collectively live and be this way despite what industry tosses at us.

I often hope (not sure if it’s realistic) that “We, the people” will establish ourselves in a more ready way to work locally to volunteer ourselves into a better way to participate in local governance even if it’s only to make existing leadership transparently accountable in the everyday. There are many small groups volunteering into the lives of those needing support at home ranging from free house repairs to cooking meals for needy neighbours with children, the elderly and disabled and so so on. I have always said that all disability is the responsibility of the whole town and not just the relatives and friends, social services, healthcare or the government particularly; I hope that I see changes come sooner rather than later.

I cannot possibly thank you enough for sharing your experiences. I read, with pleasure, every one of your blog entries no matter what else might be pending.

With regard to your comments on towns creating restoration facilities: Almost 40 years ago I had the pleasure of a special tour of US Government buildings in Washington. Each of the Houses of Congress had their own workshops in the basement with as many as 15 skilled woodworkers assuring the continuing restoration of woodwork in the Capital and Houses of Congress. Although the often used machines, they carefully duplicated the manor of construction of the existing millwork. Besides myself (I made a series of gavels) only one other outside supplier was allowed to do those Government projects. At the time, they had been doing it for over 130 years.

I’ve been thinking about this response for a while. I agree with what you say. We moved to the town we live in when my daughter was 1; she’s now nearly 13. As such, for many years, we were busy raising her and didn’t have much time for community involvement. When Covid hit, we had more time. My wife and I joined (virtually initially) several of the groups in our local church. After the vaccines, we started doing some volunteer work with these groups and are now quite involved helping the needy in our local community. This had a big impact. For years, we had talked about retiring and moving away to the point where we took many road trips to examine areas (we had a criteria list). Somewhere along the way of doing this, we realized that we really like where we live and are highly unlikely to move (though I wish I had move room for my shop and my wife had more room for her art/crafting hobbies). What changed? I think it was mostly the local involvement in our community and helping others. It has really changed our outlook on the local community. As such, I think you are 100% correct. Volunteering and acting very locally makes a huge impact. If a much larger portion of local populations did so, things would get much better in most communities.

There is much to enjoy in slowing down and searching for the details hidden in plain sight. Thank you, Sir.

Friday night it will be for me a pleasure as I rock our 2 year old grandson to sleep. To watch his face as he smiles in his sleep is a time of gratitude for me. God willing we will be at the donut shop for breakfast early Saturday morning. My work shop gets a day of rest. A great trade off for me.

Fascinating! Thanks for sharing.

A fascinating read as always, and I’m glad to hear that I’m not the only one who spends what seems like hours working out how buildings and furniture were designed and made, not to mention photographing joints and the like.

Regarding the cork oak, not only is it a regular supplier of cork, but the oak woods themselves are a phenomenal habitat for nature. Having visited and spent time in them, I can attest to what wonderful and vibrant ecosystems they are. If we, as consumers, start to buy bottles of wine with screw tops or plastic bungs made to resemble oak, then the need for those trees will decline as a consequence. This is already the case, and once it’s no longer deemed profitable, you can be sure that those trees will quickly disappear. Consumer power is a real power, as long as we are prepared to make sacrifices buy not simply buying the cheapest, then hopefully these lovely trees will continue to thrive.

I hope you’ll forgive me for standing on a soap box on your blog Paul, but I believe that saving traditional industries and resources such as the cork oak, are in alignment with the ethos of hand tool work that defines all that you do.

Paul, Many thanks for these wonderful pictures from the Woodworking Carpenter/Maker’s from the past! Very interesting plus a valuable knowledge for everyone of us!

Yes, fascinating. Wonderful article and insights.

Hello Paul, thank you for sharing this story. As a Portuguese, I understand what you mean when you say some of our heritage could be better preserved if local communities engaged more into forming these artisan guilds. While we do have a reasonable and growing sense of conservation of our heritage, I reckon Britain possibly has some of the best examples where local communities join crews of volunteers, and keep so many things alive, such as old railway stations, or local museums dedicated to preserve engineering relics or other crafts.

I’ve been in London several times, but never had the opportunity yet to really travel across Britain. I look forward to do so in a few years, and visit some of these fascinating sites. Thanks for your kind words about Portugal, I hope you will be able to return and visit some more of our beautiful country.

“ they will build houses and live in them, and they will plant vineyards and eat there fruitage. They will not build houses for someone else to inhabit, nor will they plant for someone else to eat. For the days of my people will be like the days of a tree, and the work of their hands my chosen ones will enjoy to the full. They will not toil for nothing. “ . This is a statement made about 3 millennia ago by a man named Isaiah; what he states will happen is a longing that we just naturally have as evidenced by the statements by the statements in this blog, imagine what life will be like when it happens.

Dear Mr Sellers,

Very interesting post, thanks as always for sharing your “woodworking lifestyle” that is so inspiring to so many of us. Your comment about the moldings on the first door photographed being machine-made because “curved” at the end of the rails reminded me of a question I’ve always had: how were curved panel moldings made on XVIII century french “armoires” (high dressers), for instance Louis XIV or Louis XV styles? They usually have very irregularly shaped rail/panel decorated doors, with the rails showing strong curves, lined with molding.

Best regards

Hi Paul ,

A fantastic post.

Little did you know that you were as close to being in Canada when you were in Portugal.

The month before your trip our local tv station sent one of the morning shows personalities to Portugal to show us all about cork and how they harvest and grow it.

I think you were as close to meeting me in Hamilton, Canada as CHCH tv was there to show it all.

I’m glad you enjoyed a much deserved rest and to visit family.

Doug in Canada.

Another beautiful article Paul, thanks. I’m intrigued by the desk (or side table, I’m not sure) where you consider the saw kerf in relation to its maker. It has a dovetail in the underside of the top, and I wondered if you could shed light on that? Is it a mechanism for holding the top to the bottom, or a repair? Also, directly above it, it appears that there are two plugs (either hiding screws, or perhaps they are just through dowels), and I wondered what they might be for? Just curious, perhaps you never got the opportunity to investigate beyond the photo.

Also, I love your thoughts on culture. As someone who has worked in offices for a few decades, distinct culture has largely bypassed me (as in participating, as opposed to observing). It strikes me that I have been part of a middle class global monoculture (a-cultural, perhaps?), with ever increasing homogeneity. My children are currently being brought up in that environment and it feels that there is less and less that I can do to influence that (and perhaps I shouldn’t). I foresee change on the horizon, with the decline of fossil fuels however, but it may be the generation that follows theirs that feels that impact. What will be will be for me, but I do hope they live to see the return of the beauty and joy that nature, and culture in nature, provide, in a community setting.

Mr. Sellers,

Thank you for this wonderful exploration of human endeavor.

I spent some time in southern Spain and Portugal last February. Evora was one of the stops on our travels. And like you I found it inspirational not only for its connection to history but for its richness of life, culinary delights and its mysteries.

Throughout our travels I, like you, could not help but reverse engineer the byproducts of human design, engineering and esthetics that have endured through the ages. It has informed my own woodworking as has the latter informed the former. I’m now steeling my nerve to make a Moorish inspired entry door. The knowledge base to do so is overwhelming yet inspiring.

Safe travels and thank you.

Carl S.

This is one of your most deeply felt, beautifully expressed, and wonderfully photographed posts! The way you combine philosophy and expert practical detail enlightens us all. Thank you so much for being you!