Why No Complexity

There will be a percentage of you promising makers who are looking for more than I am prepared to give you and an explanation might be helpful. In furniture making, there are many a thousand different styles and anyone studying furniture making will soon discover that there is the simplicity of vernacular furniture made in past times on a local level by a local maker and the complex versions designed and made for the rich and influential over centuries past. The clear distinction between the rich and poor of old is all but gone; we have no idea who the millionaires are now, beyond the obvious I mean. And yet, I ask myself, just why do we copy something that so identifies with something 2,000 years out of date and then try to emulate what only the rich had in some vain hope that somehow it makes us enter a different class? Is it simply because we bought a power router and had to do something with this new all-empowering piece of kit? Soon discovering that, well, there is not much else you can do with it once you’ve routed out a few dadoes and a groove or two? Again, the only real skill in making a mould with it is to keep it moving in a steady, unfaltering line so as to avoid and indent in continuity and then too the burn marks of hesitation that can be very hard to get rid of and hide.

Of course, moulding does have an important place in our woodworking world. I’ve discussed that elsewhere. Though class still exists, it’s different. In the woodworking of times past, rural workers attached to a variety of rural crafts made many things wooden. Restoring wagons and carriages translated into hedge laying and perhaps some basket weaving from willow or split oak. It could be a competent farmer or a useful gardener and in a simpler, less globalised world crafts thrived on a local level. Follow on to discover the flamboyant extremes of the rich and privileged in European environs for a remarkable contrast and then we have those eschewing the excesses of an era to make more the simple statement to pursue a modest life expressing things like Methodism (the Methodist Church) and Shakerism (an unusual religious sect establishing itself in communities in the USA). These religious groups pursued simpler lifestyles altogether and saw any adornment as excessive living. The Shakers devised some pretty heavy demands on those following a cult-like existence to the point of their ultimate demise.

In a maker’s life, someone like me, making pieces full-time year in year out, can be approached to make just about any style including their own if he or she’s a designer maker. Copying a style comes with many a kind of decoration from hawks dropping on a prey to ornate mouldings and then months of work carving and inlaying incredibly extremely complex designs to decorate a tabletop or a cathedral pulpit to be nearer to his and her Maker. The excesses of the ancients in religious edifices like cathedrals and churches cover the whole of Europe with much less so in the new world. Though remarkably contrived through generations of a single household of makers, work was grandfathered down to subsequent generations even to great- and great, great-grandchildren which has always bemused me. I’m sure the men- and women-makers along with their children and their children’s children were grateful for the work that put food on the table and shoes on their feet, but I must say that there is no greater excess exemplified anywhere than the edifices visited by millions in capital cities around the world. I think that the sense of awe we feel in such grand extremes is more to do with the building’s size and clear span at such elevated heights than anything else. These things led me to think about what I wanted in my furniture and I have written on this in other places too. I care less and less for mouldings. Only two choices are available to woodworkers, vintage moulding planes or power routers. Better to let people make their own choices. To mould or not to mould, that is the question.

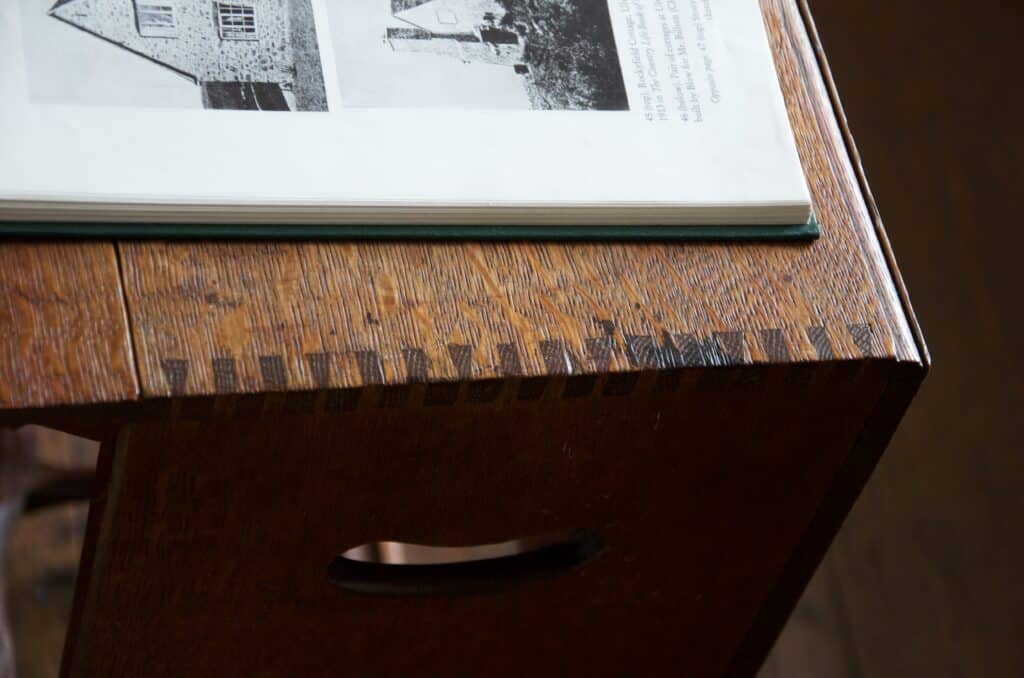

There were many makers who left their mark more by the simplicity rather than the ornate. Go into any of the ancient public buildings throughout Europe and the carver of motifs and scenes is more likely a lost and unknown name though there be no signature beyond the style of his working in the round. Of course, the famed architect’s name is plastered in books everywhere, as is the philanthropist supporting the making of such creative work and then too perhaps the signatories at the head of the tables of altruism. And let it be known! There is some very remarkable work out there to be studied and understood. The wormy handhold above is many hours if not days of work. No one anywhere in the world could afford to buy the volume of work in the building this picture was taken from today. Multiply this a million times and you can see how cheap a man’s creative labour was through several centuries and much of it in the names of religions.

So we come to the present day and the current work of Paul Sellers from the mid-1900s on through the first quarter of the new millennia. Do I admire that the Shakers and the Arts and Crafts movement who brought in or back a simpler styling? Well, I think I would say I respect what they offered to the world of design, yes. They are indeed a part of the greater whole, aren’t they? There is something very special, unique even, about the maker whose skill lies in distilling things down to the raw energy pure functionality brings to a design. Now I am not talking about mass-made utilitarianism evident in institutional venues. No no, that’s a whole different other world. This might help: I recall taking a Stickley chair in for repair some many moons back. The simple-looking chair stood atop one of my two benches for a few weeks, primarily because its owner disappeared without trace for months and my price for the repair wasn’t yet accepted before his disappearance. I could neither work on it nor return it. Over the weeks I found my eye repeatedly drawn to certain facts about its design. I saw a difference between the greater randomness of the stick chair makers cranking out parts by eye in woodlands around England and then how rigidly the Stickley maker had complied with the parameters of spacings between mathematically positioned rails in diminishing distances for the purpose of establishing standardised designs to be produced with ease of repeatable manufacturing that would be faithful to the design and the designer. There was nothing freeform to the design. Every curve and rail, leg and taper was proportionally calculated. How the man-maker was being conditioned by the designer to follow extremely rigid patterns to ensure the design was the designers and not the makers. . . so very critical to any designer’s work.

My repair eventually followed and the work was completed and paid for. There was little interaction between this disappeared man and myself, just a basic gratitudinal letter for saving one chair as part of a suite of six. And so the skills of the repairer were subsumed into the greater whole and no one knew of the work of the whole. Months later another such project came in. These medallions were not particularly complicated but they did bore me as most carving seems to do to me. Every so often though, you will indeed see the work of an individual that just translates you into new realms. Often something truly simple in appearance but then the more you look at it the more you see the art was less in the carving and more in the placing of each well-chosen and composed piece. You look many times and two hours has passed as you catch different glimpses in the twist of a gouge or a chisel’s cut. Getting your work to go beyond the wood to make what’s carved look less, well, wooden, is where the art in carving lies. I once watched a carver carve his own image of himself full size and wondered where this piece would ultimately reside. Would he sell it and if so who would buy it? Would he keep it and if so would it stand on a sideboard in his living room? The work was incredibly executed and it did make me think about something called carving graven images.

Our work of recent years has led me to design pieces that will enable and equip people to become skilful woodworkers. Adornment would be of secondary interest and value to the construction techniques and methods used. Anything that we have made on woodworking masterclasses can always be embellished with additional inlay work, veneering, carvings and mouldings or whatever. I have many pieces that we have made in these recent years that I have and am enjoying these days. Most of them have no moulding to them. Why? I think using mouldings somehow dates your work. It ties to a past era, yes, but it also ties it to the power router and mass-making methods I try no longer to include in my work. In essence, moulding make me reliant on the design of others–classical Roman influences and such. But worse than that, it ties me to a machine I would rather have as little to do with as possible just because it is so very invasive.

Using the dining table and chairs at the house brought comfort and personality to the dining kitchen and, of course, personal mental comfort for the designer maker. I prefer using the wood as decoration rather than three-dimensional carving and mouldings which often serves more to clutter a design. I prefer the concepts of the wood itself texturing and decorating the work and using textures on wood surfaces without too much human interference. Several things strike me about using wood without adornment, perhaps its near natural condition as possible, one, its diverse colour options, two, its grain type and configurations and finally its texturability. hand tools of different types texture wood remarkably well. From wire brushes to carving tools and paints for colouring alongside gold- and silver-leafing and fuming with ammonia. It wasn’t really my intention not to carve or inlay and so on so much as by not using it it became a statement in and of itself. suppose, but that wasn’t really so much an intention as a way to break up the monotony of a room with all of the same wood. Eclecticism is a form of decorating and an arrangement of different woods composed in unique designs can be, well, exceptionally entertaining. When my two new cabinets go into the same dining areas as the other pieces there will be an interest for any eye that comes.

Three kinds of wood in a single piece is not so unusual but here in the UK mesquite is amongst the rarest of woods adding personality to a nostalgic past recalling and recording some of my journey to now.

Quite nice to hear your philosophy. I’ve been following your classes about 8 years now, and I’ve been thinking a lot about my own strategies for adornment or decoration. I’ve tried inlay with the most success but I’m interested to try marquetry as well. I can’t carve for beans, and I dont own a moulding plane but I do have hand power router I sometimes use. It’s a long quest to find one’s style that leads to that harmonic sense of fulfillment in the maker.

I’ve made several of your occasional tables in various sizes. Every time I’ve been shocked how lovely the exposed end grain is on the tops. Our local Starbucks has a wall of oak ends (4×6″ or something) glued in a sort of brick pattern and tastefully stained, and it really is stunning, the medullary rays shooting through like a bunch of little negative sunrises.

My anticipation of the wall cabinet project continues to increase. Concealed back — no through motises on the divider — contrasting wood edges on the doors. Also the YouTube video on the house was very exciting, bedroom furniture (some disassemlable) is precisely what I’m in need of. I will add, if a disassemblable, smallish dining table ever comes up for consideration, that could be useful for those living in apartments.

Lovely what you did on the cabinet side panel, gluing the lightening edge up against the darker edge. I would’ve put it that lighter edge on the back and thrown away all the visual interest as a result. A good example of how the design philosophy articulated in this post is much more than just “make plainer stuff”.

Thanks very much.

I make furniture, currently table lamps. My idea of complexity involves the spacial geometry planes and angles and massing found in great architecture, particularly the ideas introduced by people such as FLW, Van Meis, the Greene’s, and later makers such as Maloof and Krevnov. Simplicity can be very elegant, profound, and hard to achieve.

Hi Paul, a very interesting blog. When you mentioned vernacular furniture especially in the UK, imagining all the local craftsmen who made this incredible furniture for the ordinary people. To make it affordable and to make it functional using basic tools home made usually and skills past down to them through many generations is an inspiration to me. They didn’t expect much in life, and it’s a good job they didn’t. We don’t know who these people were, but there furniture is still there as a testament to there skills. May be they didn’t want to be known, but just to make the best they could and keep food on the table. Tell me the name of one country vernacular furniture maker from a hundred and fifty years ago. But we all know Thomas Chippendale.

Looking forward to your next blog.

In a caption above, you say “… none of my audience has time for such adornment.” I would argue that is not true. Many of your followers are, no doubt, retired and do have the time. For my own part, I’d love to learn what it takes to add interesting carvings and traditional moldings to a project. Just saying …

Then I should have said, going off what people tell me, the majority of my audience are time-strapped. I believe that is the case for working families with both parents gone during the week.

There are some good choices for learning some traditional carving online, e.g., there are instructional websites by Mary May and Chris Pye. For example, as far as I can make out, Mary May specializes in furniture decorations such as acanthus leaves — her specialty.

Dear Paul,

reading your blog always give me great pleasure, and makes me think. Though you have often spoken of it before, your aims and views on your craft has not been better stated than in this posting (at least this is the impact on me). So I just want to thank you for yet again informing, bemusing, and to an extent provoke me – to make me reflect on life and craft.

Yours,

Baard

What’s the rush, I’d like to ask the hobbyists? Why are they in such a rush to get it done? Don’t they enjoy the process or are they still in the typical “I want it now” mindset. However, as a professional woodworker, you charge accordingly if you are hired to add carvings, mouldings, or both.

I love those elements of adornment which lift a piece of furniture from the run of the mill. It may just be tiny hand cut dovetails, not made for examination in the ordinary sense, but exquisite nonetheless to we woodworkers who appreciate such skill.

Robert Thompson of Mouseman furniture made beautiful but everyday furniture up in Yorkshire. His inclusion of a raised carved mouse on each piece lifted them from just very nice to sought after pieces which are very valuable to this day, and still incorporate a hand carved mouse. He learned his trade as a boy and was involved in the restoration of wood in ancient churches. Apparently the mouse carving came about as joke about his being as poor as a church mouse.

While not quite the same as intricate carvings or mouldings, I found a very early drop leaf, or gate leg oak table on the pavement outside a junk shop. It has turned stretchers and spindles whereby the craftsman’s tool marks are still visible. To my mind, these somewhat crude, uneven pieces, probably turned quickly on a pole lathe are beautiful. The circular top is made from just two huge planks of oak. Over the centuries, damage has been repaired in the top by sections being chiselled out and replaced with new wood. Although done for practical reasons and not for aesthetics, the effect is beautiful and unique.

To me, this table isn’t valuable in financial terms, rather in the story that it tells.

Thank you for another very stimulating post – I enjoy your philosophical offerings more than those of a practical nature (although those are of course much appreciated!).

Being a retiree, and amateur, I have had time to experiment with carving and the use of moulding planes and enjoy the processes immensely. However, when it comes to the design of furniture, boxes etc. I find that what satisfies most is the pursuit of simplicity – in my case Arts and Crafts inspired.

You speak of moulding and other decoration as dating the work, but if you will forgive me, I find your designs sometimes appear dated, reminiscent of Ercol and G Plan. This is not to criticise your obvious skill, but simply to raise the question of how we should approach design, given the wealth of historical precedent.

I enjoyed this post as it made me think about why we might take up wood working in the first place. In my case it was as much money as enjoyment. I couldn’t afford to pay a craftsman for what I wanted so I learned to do it myself.

I do have a plenty of wood working machines and use them all as I see necessary. I also have a full compliment if hand tools and couldn’t imagine working wood without them. All my joinery is done with hand tools, as well as making and flattening panels.

Paul you vocalized something in this post that I have often thought about. The craftsmen and women in the past toiled making incredible works in churches, public buildings, and as laborers for the likes of the Chippendales and his ilk. Those workers couldn’t afford to buy such luxuries for themselves yet their names have disappeared in history while the patrons and Masters go on centuries after their deaths. Their work was honored but they were not. Seems so unfair. I like to think of them stepping back and admiring their handiwork smiling to themselves, maybe carving their initials in an inconspicuous spot.

I love many of Paul’s designs, a few not so much. I am not so much concerned about his designs, as I am learning his techniques and wisdom from many years of woodworking, and they way he lays it out in a manner easily understood.

My own workbench was built from another very good woodworkers plans, long before I ever heard of Paul. I didn’t like many of the designs of this other man’s creations, but I was impressed with the quality of craftmanship he used. His workbench made sense to me, and was smaller than many, so it would fit in available space. It is still sturdy, and I have a removeable top on it because it sometimes doubles for a desk, a mechanics bench, and my grain grinder is used clamped in the vise.

I too tend to like simpler designs such as Shaker and Country furniture, now often called primitives. I also appreciate cabriole legs and some simple carvings. If I were to attempt something more ornate, it would be because I like it; not to impress anyone with my wealth, not that I have any!

Paul found the niche he likes, and I am happy for him to make what he loves.

Interesting comments on Stickley’s furniture. My understanding is he wanted the craftsmen who labored in his factories (and, by extension, all factories eventually) to enjoy the the results of their labor by having the “Grunt Work” (rough dimensioning, etc.) done by machine and then do the finer work of fitting the joints, assembling, finishing, etc. and be able to take a certain pride in the result. They were engaged in making affordable, unadorned furniture for the rising middle and lower middle class that didn’t look and wasn’t shoddily built as the typical over adorned factory wares that were sold to the general public in the mid 19th to the first quarter of the 20th century. I don’t believe he, nor any of the others in his sphere of influence ever said that if a home craftsman wanted to build something in his style that they had to copy each and every dimension exactly. It’s different in a factory when your making many multiples of the designer’s product to their specifications to achieve a certain price-point – especially when the product seems to be attractive to the intended purchasers.

There’s been more than one new business started by an employee who thought he had a better idea and left the place he worked to start making their own (“New and Improved”, “Hand Crafted”, etc.) versions of whatever the product was they’d been laboring to make as an employee. More power to ’em.

As to following the “Exactness’ of another’s design, I suppose it depends, I imagine you followed the dimensions that were laid out before you or I were born when you built a cello. Just as many do trying to emulate a Stradivarius.