Sensational People

Sensational people were not exhibitionists but ordinary workers making. There was no acting and no faking.

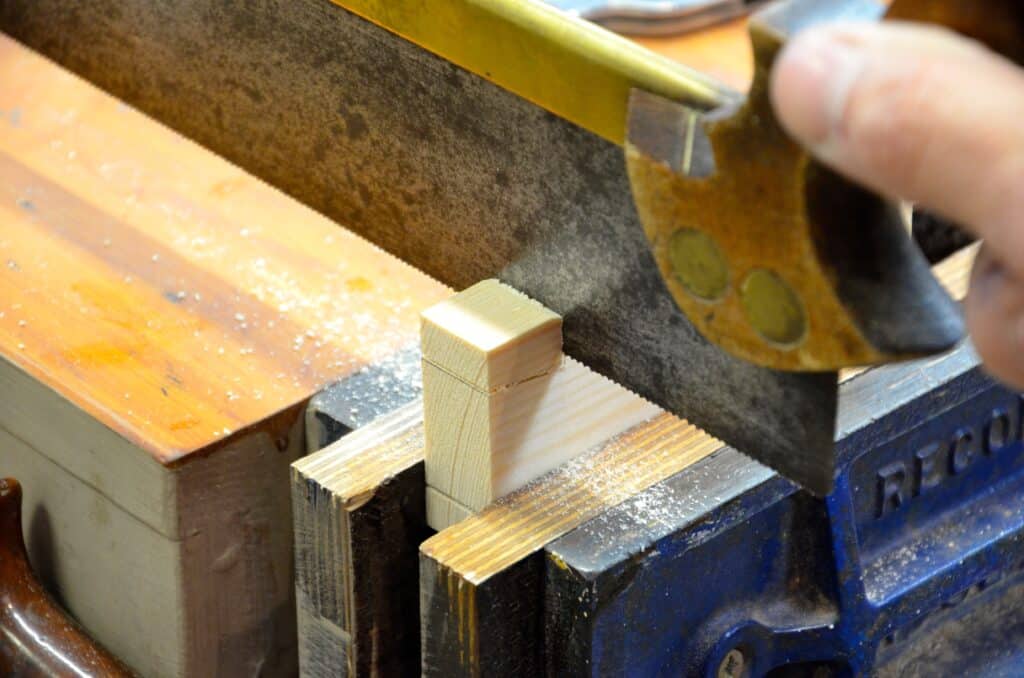

I remember watching George make a dovetailed corner to a cutlery tray with divisions for each type of eating implement using sycamore offcuts kept after our making draining boards for a school’s commercial kitchen. Each move was deliberate, unwavering, incredibly direct. A dovetail quickly formed became template for the pins. The pencil came to sharpness from the chisel’s edge twice to lay down pristine lines black on white with the light fineness that became unordinary. Back then I recall him squaring the ends of thin wood without the aid of a shooting board using only the briefest glimpse and glancing placement of a square alone. The ends gleamed beneath the fluorescent lights as he twisted and turned them in and out of his Record quick-release vise and then came the tap tap tap of his Warrington hammer as the dovetailed corner seated one piece to the other. This pattern of working, fits coming straight from the saw, airtight joints utterly gapless, taught me in a matter of two minutes how to cut dovetails. I never used any other method as a matter of course. Pins first seemed backwards and illogical and I never resorted to substitutes for skill.

He passed the next corner to me and I stood transfixed in a stare eying each piece end in incredulity. He expected me to repeat what he’d just shown me with no words of explanation. His gently laughing as he passed me the dovetail template told me this might not be as easy as he made it look and he had not used it on his corner but then he said, “No ruler though.”

The saw seemed heavy in my hand somehow even though I was now using it daily. It all related to the thickness of the wood, the size of the work and the relationship between the saw to the lines. Today, I anticipate grains by knowing their fibrous innards. What? Internally I grade woods by my reference of decades of experience. On a scale of one to ten oaks come somewhere between 8-10 whereas maple comes mid to lower and many exotic woods come in at one to two. Ebonies are a solid mass where grain can sometimes seem non-existent. Pick up an old bowling green bowling ball and you will understand what I mean. Oak on the other hand will be half or less than half that weight. Gaboon ebony, very endangered, weighs in at 70lbs per cubic foot while red oak is 45lbs a cubic foot. Back then I had no terms of reference. Woods were all the same — pores, hardness, density and such meant very little to me. My sycamore felt somewhat soft and lightweight (34lbs per cubic foot) but when the saw entered the wood it seemed somehow to be gripping the saw plate.

I had placed the lines by copying George’s, roughly. They looked right, spaced evenly. And two dovetails are easier to visualise spacings for than three. The width of my wood was 2 1/2″ (63mm). 7/8″ (23mm) dovetails gave me 1/4″ (6mm) pins, near enough.

My saw did not glide as George’s had, slipping into and through each cut kerf as smoothly and effortlessly as always. The edges of my dovetails looked a little jagged as each stroke left its ragged trace of even the slightest of wobbles. I can’t remember whether I was conscious of this or whether the evidence came when the two parts were married. George’s even hand, steadily powered through with far fewer strokes than mine. And then there was the chopping. Hmm! Knifewalls were not called knifewalls then. I created the term to have the word describe what was being created with the knife: Marking knife seemed so inadequate and more apt for timber-framing and general carpentry. I’m glad that I had the foresight — striking knife was the same. I am sure George would be surprised by where I am now, 58 years to the week later. Blogger, influencer, knifewall. Such terms didn’t exist back then and neither did any of the social media or even the term exist either.

Surprisingly, my dovetails did come together and held. I did two and George did two and the foreman, Jack, came over and took a look at them. Taking his glasses from his forehead he looked over the top of the dark tortoiseshell rims and smiled. “Not bad, not bad!” he said, nodding. “They’ll be better next time. Do it again!” he said. And I did.

In the mesmerising world of YouTube, we often see the ordinary sensationalised by something sped up by time-lapsed, almost instant videography. Cuts and edits come almost instantly at expert fingertips dancing across a keyboard. It’s easy to forget that handwork skills must be developed by rote practice and that it will take time and repeat processes to understand the complexities of various wood types, how the tools work with them and then our humanness relating to everything. Usually, few of us own skilled and ordinary work straight from the first try. To own it we must expose ourselves to our own weaknesses. So many times I have seen the obvious become confusing when my hand, my arm, my eye and my body seemed incapable of doing what I felt was completely understandable. The ordinary now unseen in most crafts owned by the ordinary man and woman seem to me all the more extraordinary now that I am an old man. 200 years have passed since the man and the woman warped the loom, spun the yarn and wove the fabric. George and Jack, the ordinary, showed me the better way of patience and skill so that I could truly own all that I would need for sixty years of making and selling and living a lifestyle of making all that I loved in the making of things wood. It’s the ordinary that reserve the right as extraordinary people to be recognised.

Hello Paul,

I’m consistently amazed by how your training in learning your art parallels that of the old time way of learning to play a musical instrument well.

Thank you.

I often think and write about composition in my work. Even when artists defy the norms they seem always to be undergirded by what I call the order of composition. That’s the verticality and horizontality of lines placed on a page developing into nothing but curves, angles and slopes resulting in ‘the golden mean’. This ‘golden middle way’ is essentially the placement of an end result of those striving to establish a balanced presentation of something between two extremes, excess on one hand or deficiency on the other. Greek thought was to establish nothing of excess but of course, art of every kind has and will always push at the boundaries to the extreme.

Learning to live within the boundaries of our creative habitation brings a certain peace where we accept the foundational teaching once transferred from master to apprentice and usually steadied by their hands with concepts of constraint meant not to harm but keep safe.

I’m sure you’ve covered this somewhere already, but WHY are houndstooth dovetail joints stronger and when should they be used? Thanks for your incredible teaching, I love being a subscriber to your Woodworking Masterclasses!

Though it may well be used as a sort of show-off dovetail joint, and that may well indeed be why woodworkers put them at the forefront of their work, in actuality much greater strength comes from the combined interlocking angles in juxtaposition together with the resulting added friction surfaces within the joint. Additionally, this doubling of the meeting surfaces adds a much greater expanse of the glued surfaces too. We use it when we need to use a thicker drawer front or for the corners of stress components like those often used on wooden vise jaws. Its superior strength gives much greater resistance to separation than the common or through dovetail or half-lap dovetail. I think that the making of the joint is one of those things that educates you as to the reason things were done. Everyone should make qt least one.

Not sure if you’ll see this five days after the fact, but I wonder, how would a mitered dovetail fair in your strength comparison of dovetail types? Is this joint closed purely for cosmetic purposes?

It is. And the only time I tried to dismantle one I couldn’t so I left it. I still have the desk.

George would be proud to see his teaching skills and kindness passed along to hundreds of thousands people throughout the world. Both in your work and even more so in your blogs.

why are houndstooth joints stronger?

I was wondering that too and found the answer in a previous blog by Paul: https://paulsellers.com/2011/04/hounds-tooth-dovetails/

What the heck is a houndstooth? Is that doggie dental care?

I wanted to ask you re: the ordinary: were you an ordinary woodworker that became a superstar? Who was the best natural woodworker in your shop…not that this is important, just curious if you learned to become outstanding or were outstanding and put the tip on the pencil so to speak.

The short answer:

So many terms once commonly used and never questioned are lost in craftwork because the craft itself is gone. Using the imagination just a little, depending on how a dovetail is laid out and the size and proximity of teeth one to another, a hound’s tooth dovetail can look like a snarling set of dogs teeth or when you fold the lips on a dog back (gently).

I have never pursued becoming better known as any kind of target in the same way I stopped working for money 30 years ago. The more important thing for me was to fulfil my calling as a maker and then, more importantly still, to teach others about life as a crafting artisan. The outcome of making for a living and not for money was that I simply earned money as a byproduct, enough to provide for a family as a single-wage earner. The outcome of addressing the imbalances that show machining wood as the new way and only way for modern woodworking raised many eyebrows 30 years ago and because I saw the two methods differently than most I faced considerable opposition from machinists. As I wrote for US and UK magazines about hand-tool woodworking only it became evident that something was very different. The magazines took every article `I wrote and constantly asked me for more. I realised that my advocacy was just new wallpaper for their advertising media-owned magazines with 95% of advertising coming from machine manufacturers and distributors who could afford two-page full-colour ads. But then the internet started to open up. I started blogging with a difference. I think many new gurus have tried to copy my work and methods but as someone once said, “They have a bucket while you have the well.” Experience has given me the greatest advantage. I gauge my success by how few invitations to write and present I get these days. I did get a couple of invitations over the last couple of years to teach back in the USA (which I consider as much my home as the UK if not more so) but I really don’t want the hassle of teaching for other companies. I want to take a two- or three-month sabbatical to travel the US and meet woodworkers en route at different venues. I’d do this in a VW campervan if possible but we’ll see. During my future travels in the US and then Europe too I plan to complete some writings for books I have in manuscript form currently. My legacy will be the conservation of handcraft in woodworking but I also plan a small how-to on machining wood to show how you can minimise the impact and better relate to hand tools. Doing this in a campervan might not be so easy.

As to being outstanding. It is not modest to state that I am a pretty ordinary craftsman who just does it and who was advantaged by living as a producing woodworker selling his work throughout a six-decade span of his life to date. None of this makes me any better or worse than any other woodworker; I had a lot to overcome to present to the camera and be conscious of others on the other side of the lens. The only, ONLY, difference I have found is my long-time concern that without the input from amateur woodworkers on a global scale we would lose the craft and art of woodworking by hand. I feel completely successful now thanks to the support that only came because of the internet. Reaching the millions that I do throughout the years still shocks and amazes me. I’m not the only one. Many others who would never make it as makers can indeed make videos and make a living via YouTube. Gurus have families to feed and mortgages and rent to pay. Their reasons for doing what they do is as valid to them as mine is for me.

Re natural woodworkers. I have worked with so many through the years it would be hard to say. I do think they all pretty much loved woodworking. My US apprentices had a natural ability and were often supported by their spouses or parents. Some had the proclivity straight off and others had to really apply themselves to master even simple elements of becoming what they seemed awkward in.

There is a strong need for woodworking magazine articles about hand woodworking. Most seem to assume that hand includes a plethera of machines. I can only assume that the writers are sponsored by the manufacturers. I bought a couple recently, I should have realisaed that they would disappoint. One used a router to round over the corners on a birdbox, even though the rest of it was made by hand.

You’ve got to remember what pays the bills and the director’s bonuses, Kieth. It’s not hand tools. I am sure that magazines outside of fashion and such are on their way out and especially woodworking versions.

KeithW: let’s start the all-digital Hand Woodworking Magazine: you have to do most of your woodworking using hand-powered tools. I bet there’s enough of a critical mass of us to subscribe and get the word out. Keith, you’re the Editor-in-Chief! There’s tons of demand and this website proves it. And we stand on the shoulders of giants. Plus with as expensive as hand tools are now, they’re plenty of money for salaries and paying the bills. One Lie Nielsen or Bad Axe tool is like 200 – 700 dollars+. I just bought a froe for $118! It is a piece of metal on a stick. Ebay sells old tools for at least $100 a pop.

It’s not $4000 – 8000 for a machine, but how many do you think they sell per month. Probably they sell a lot more smaller items than the big expensive ones. There are a lot more poor people than rich ones after all.

PaulS: Thanks for the thoughtful and humble reply and…you’re so full of it! Ordinary by no means. I don’t know any average woodworker that can start a movement that will outlast all of us. Or can write with such ability. Or is patient enough to answer my never-ending questions! Or has the stamina at your or any age to work like a machine (pun intended). Or inspire the entire world through videos and your team to want to work the wood the hard way. Heck, I might even go out into the workshop and actually do something! Extraordinary!

When I have a birthday, nobody wishes me well. They say drop dead Jeff D. It is my charming personality, i think. When Sir Paul has a birthday, the whole world rejoices to get another year of the master and mentor of wood. Everyone on this blog and WWMC feels that way.

Hi Paul, I believe I read that you made some furniture while you were in the U.S. that is in the White House. I question what items you made and if you would be willing to reveal them to us. I would love to see you reproduce those items. I really enjoyed the things you made for your current house, they are so beautiful and pleasing to the eye.

Thanks for all you have done to keep this wonderful art form alive!

Warm regards, Bertman

Just google Paul Sellers and the White House pieces. It’s all out there.

Paul, Thank your for sharing your knowledge with us by using the new technologies and embracing it to teach, but without jumping on the bandwagon, and trying to adopt the trendy “influencer” habits that I see on the Internet, and Youtube. It’s a useful tool if used correctly, and really the only way to reach people these days, it seems. I also appreciate your Common and Master classes websites.

I usually spend the last hour of each evening, when my eyes are too tired to read my book, but too early to go to bed, scrolling through Youtube, and usually watching woodworking videos to wind down. So many of them just make me cringe, from the thumbnail images on the index pages where so many woodworking “influencers” (I don’t care for that term, either) and wannabe-“influencers” feel compelled to show their thumbnail image to their video by making a weird funny-face while looking at tool or object. I find that creepy and real turn-off, and wish people would stop doing that. Then of many of the videos I do watch, they are often full of unnecessary camera tricks, like slow-motion hand-plane action, annoying he-man rock-music chords like they use in home center commercials, and generally a lot of video footage that doesn’t teach me anything useful.

I know for many, the name of the game is garnering views and getting likes and followers. But if you actually provide useful content and can teach, the views, likes and followers will come. And that’s what you do. Without gimmicks. Without a lot of fanfare. You just do. One phenomenon I’ve noticed while watching your videos is that I often catch myself craning my neck to get a closer look when you are doing something like, say, close-up chisel work, as if I was in your shop with you.

I hope you don’t take offense to me making this comparison just because you are both British, but watching your lessons reminds me a lot of reading A.A. Milne, where I end up just feeling calm and feel like retreating to the Hundred Acre Wood. But most importantly, when I watch your lessons before going to bed, I almost don’t want to go to bed, I want to stay awake and go out to my workshop and say to myself, “I can’t wait to try that!”

Thank you for sharing your knowledge the way that you do.

eloquent, generous, patient, calming, enlightening, motivating, and so much more. Watching Paul reminds me of the late Jack Hargreaves, or Bill Mason. Honest and reliable pearls of useful empowering knowledge.

I feel as though anything I would try and put into words to acknowledge or respond to your amazing comments in reply to some of these questions, would ruin your elegance and prowess.

When I describe Paul Sellers to people who I know have never heard of you I describe you as a living Leonardo Da Vinci. Woodworker, teacher, artist, educator, engineer, designer, etc……

This country welcomes you with open arms. Thankyou.