Lofty Heights

Oxford’s a place that will never be built again. Streets paved with educational gold, one street after another built of solid stone, stone on stone clad above by slate roofs draining rain into lead gutters, catchments and drainpipes. The carved handwork in stone and wood takes the eye in every direction and even then you miss 99% of what’s on the outside and ten times more on the in. There it stands, plumbed, set square one block to another and each building to another and every time you go there you wonder how you didn’t see this and that before and then what lofty heights those designers of fine buildings went to in their minds to design and then build what would last for centuries yet after centuries show little sign of collapse or decay.

Future-proofing buildings in weather like ours was the universal forethought of architects with access to mass of both materials, stone and slate, and then those man-makers building three-dimensional realities into being and then who saw generations in the same families take up trades taught to each passing age by grandfathers and fathers. We don’t think in those terms any more. I doubt the architect in IT is wishing the craft for his or her children and grandchildren because nowadays they think of generations of software upgrades minute by minute at speeds the speed of light. Back then it would have been greater investment in survival for each as an artisan and the passing on of trades from father to son and mother to daughter. The buying of people to build and make for the lowest possible wage kept the rich rich as they bought the poor and kept them in their place for centuries. Go back as little as a hundred years and then think mid-1100s when Oxford as a university town is first mentioned. A thousand years of building a University that stands reputedly amongst the most prestigious in the world.

I look in corners behind the metal and wood and stone for my information and the intelligence of the man-maker making the work of the architect stand 300 years in front of me. I see doors too heavy for hinges alone and trace steel tracks in the stone setts and cobbles now operated by electric sensors answering the calls from the cars remotely to gain access and close behind them.

The University expanded rapidly from 1167 under the rule of Henry II who banned English students from attending the University of Paris. The returning students settled in Oxford and from those days of small beginnings, we have Oxford’s City of learning.

What still stops me in my walks around town are the hidden gems in the seemingly endless masses of massive oak entryway doors. To the visitors, they are conscious of the antiquity of the buildings in a bemusing sort of way but I search out the twin tenons on 4″ thick stiles and then just how much quarter-sawn oak was used in this one town’s exterior doors alone. Thank goodness for tempered glass without which Britain would indeed be treeless. We don’t realise just how much tempered glass allowed for skimpy aluminium and plastic frames to make doors pretty much frameless and so too shop fronts on a massive scale — frameless and characterless I should say.

Here is one of my favourite bookshops. It’s been here in central Oxford on Broad street since 1879 so the relative new kid on the block compared to the ancient colleges of the campus-less university encompassing Oxford’s Colleges.

It’s the Blackwell’s cafe I like to work in mostly. Here I can sip at my coffee and draw and write amongst the budding future. Background noises seem always filled with “I” “I’m” but it’s always the white noise that more helps me than silence. I’m still writing longhand in my journals to record happenings and thoughts, ideas and completing sketches from the wilder places nearer to home. Of course, there are no truly near-to wild places in middle England any more. Unless you include conflicts between cyclists and runners in bright high-viz along with dog walkers throwing balls for dogs and arguing with cyclists trying to pass people and their dogs on extra-long leads spanning the paths as they go.

A friendly face came to ask me, “Are you Paul Sellers?” as I worked on my laptop. He’ he’d been enjoying some time in Oxford with his twin daughters and said he enjoyed our woodworking channels online and originates from Slovakia. He’d studied economics here at Oxford and settled to married life in the UK. We enjoyed our chatting for 20 minutes. It was nice.

In Oxford, we also have one really fine art shop just across from Blackwells called Broad Canvass, hinting at the street name Broad Street in the shop name, where I buy my art supplies. The staff are so knowledgeable and willing to help and you can search and buy online. If you are like me and find what supplies you like to work with you want to have a consistent supply. I have but a four-year supply of my Barns and Noble sketchbooks left because, as it is with all good things, these came to an end a couple of years ago when B and N stopped selling them. Thankfully, I’d bought a ten-year supply. They have smith-sewn permanence but extra fine and unnoticeable perforations if indeed you want to take out a page. Hannah sewed me a leather cover that has been so welcome in keeping the innards safe and stowing my pens and pencils in the front holder for quick sketching and notes.

The outer walls belie the interior blocks comprising Oxford colleges. The University has 44 colleges which include five permanent private halls, each founded by various Christian denominations and all of which retains their religious character. These colleges are small, multidisciplinary communities operating independently but under the headship of Oxford University. Each has its own gathering of students, academic staff and administration.

It’s hard to convey the mass of stonework there is in Oxford. The sense of presence permeates every ounce of space to tell you of its significance as a university town and then too the Greek influence ever hovering in the backgrounds of buildings and woodwork and of course education.

I wonder how self-important those patriarchs felt through each generation and century. Imagine those slide rules and parallel rulers slipping across sheets of paper to trace out their lines to create windows and levels and doorways to be carved out and shaped by unknown stonemasons, carpenters and blacksmiths shaping the protection of the academics who’d never lift a finger to manual work. And there was such great conflict between the town folk taken over by the scholarly; those academics fearful of injury and even life fled to Cambridge and started Cambridge University.

Cars are disallowed the more in major cities in Britain and so too through the streets of Oxford which in size (160,000) is little more than a good-sized town. Bikes can be a real issue for pedestrians who now wander mid-street to meander more than stride with purpose. Bikes assert rights no matter where you are on path or roadway and interweave in their silent passage to skim shoulders as they pass by in their annoyance. Not too well thought through at all and with near-zero policing it’s surprising that more conflicts don’t occur. I’m glad I can ride in by bus. It’s a ten-minute abuse ride for me and no parking issues so I am glad for that.

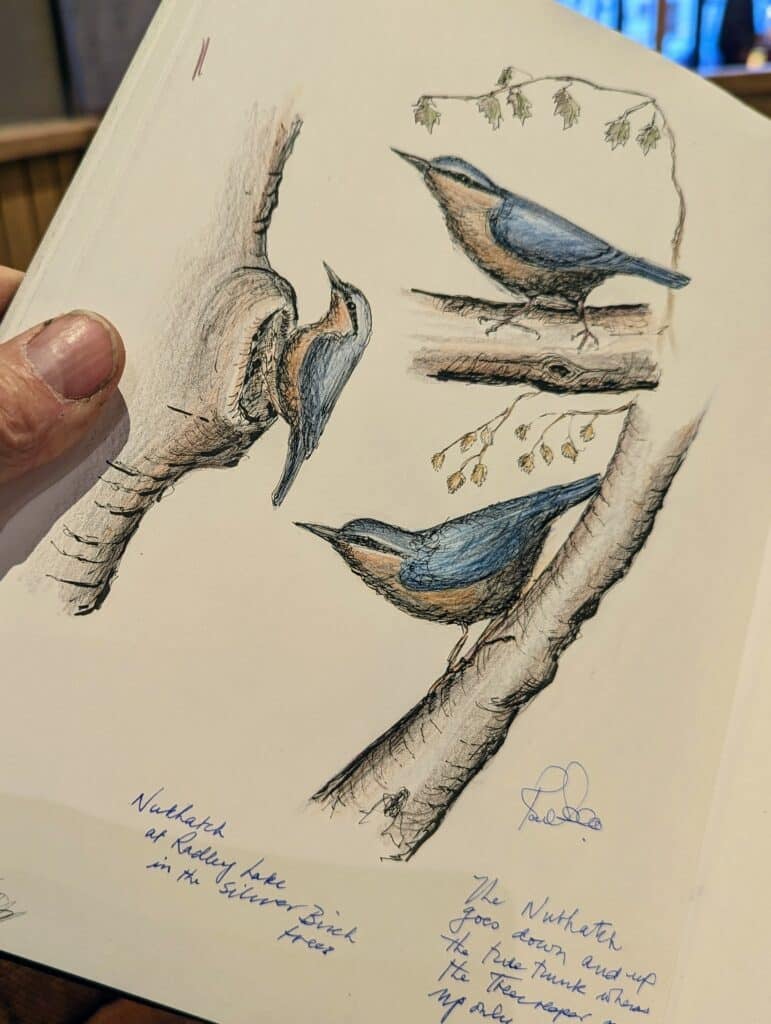

An enjoyable read thank you Paul. I always like your sketches but the birds especially jumped out at me today. I also love to see old buildings and especially the doors built with skill and care. where I live we dont have buildings like that!

Scott

It’s very nice to see that I’m not the only birdwatcher here 😃. I began birdwatching in 1983, when I was 15, doing bird-ringing until I went to the University, but I’m afraid that I can’t make a drawing of a bird like the one in this post.

Hi Paul,

My daughter had the privilege to do a summer session at Oxford while at the Univ. of Oklahoma and we were able to visit her there for the last few days. We were able to see/visit just enough to know we would need to come back and spend more time there, but then COVID hit, so we put that on hold. We’re hoping to go back this summer. Thanks for writing about Oxford (and all your other blog posts too, as one thing I took up during COVID was woodworking and your writing gave me the confidence that I didn’t need to go out by all the latest fancy power tools.)

In the mid-70s my wife & I were privileged to visit Oxford. From C.S. Lewis’s quarters to the sad spot where Archbishop Cranmer was burned at the stake, a deep dive into the history and beauty of this glorious place. The deer park brought gentleness to the surroundings.

These carved flowers are at another level, I wonder what they used to protect doors from elements at that time, linseed oil, tallow, wax, or something else? I read, 17 century carved boxes were covered with linseed oil then waxed every year or so for hundreds of years, this is how they got that brown patina. Maybe same with doors? How doors survived for so long?

Not sure where you read that but it’s not true. We think our smart finishes preserve wood outdoors but they cause more rot than they preserve. Raw wood works best. Skin finishes hold moisture in the corners and this is where the rot begins. At intermittent stages a different overseer might decide to add colour that ultimately fades in the sunlight and that is all that happened with these doors.

Oh Paul, now I will have to resist the urge of popping into town to see if you are in Blackwells so I can beg you for a weekend apprenticeship!

Not sure where you read that but it’s not really true. We think our smart finishes preserve wood outdoors but they cause more rot than they preserve. Raw wood works best. Skin finishes hold moisture in the corners and this is where the rot begins. At intermittent stages a different overseer might decide to add colour that ultimately fades in the sunlight and that is all that happened with these doors.

Not sure where you read that but it’s not really true. We think our smart finishes preserve wood outdoors but they cause as much if not more rot than they prevent or preserve. Raw wood works best. That said, skin finishes can look very nice and get you through the first couple of decades with a couple of periodic treatments. Skin finishes tend hold moisture where the surfaces at different junctures separate or fracture, especially does this happen in the corners and this is where the rot begins. In the case of these doors, at intermittent stages, a different overseer might decide to add colour that ultimately fades in the sunlight and that is all that happened with these doors.

Interesting opinion. My experience suggests that detailing is key as far as run off is concerned. Skin finishes can be problematic when breached and require regular maintenance. Impregnation finishes based upon cellulose are normally a better option. They do not coat or skin and they break down naturally and by design with UV – requiring micron testing before re-coating – if left they simply disappear exposing the raw wood as if never applied. Such impregnations prevent the UV break down of the natural cellulose within the wood fibres so the ridging of the wood is not exposed by the action of the rain. I have seen such impregnation finishes 35 years on from application benefiting from a 5 to 7 year simple recoating regime and they look fine and with no evidence of rot. I like wood left raw, but also am happy to use the correct coating system where appropriate. Too often nowadays we see raw wood cladding contemporary buildings that has weathered to an unsightly dark grey in patches which leads to replacement whilst the material itself still has years of life left within it. A simple coating would prevent such a waste.

I am told of wood shingled roofs in Scandanavia that are near a thousand year old that have been preserved by applying a mixture of raw linseed oil, pine tar, and turpentine mixed in thirds.

The problem with linseed oil today is that most of it is not properly manufactured. The hardware store brands will cause severe mildew! Even the good stuff can have some mildew in humid climates, but nothing like the improperly prepared oil. I learned that when I put some of the wrong oil on a shovel handle. I kept it off the ground, but under the house. It got a coating of mildew all over it! Yuck! I sanded off what I could and coated it with the good stuff. Much better now.

I personally tested the linseed/pine tar/turpentine mixture on a 1 ¼ x ¾ inch piece of pine. I applied numerous coats, as soon as it was sucked up, I added more to the end grain. Then I let it sit a day or two before adding more. I forget how many applications I used, but a lot more than 3 or 4. I then sawed it into pieces to see how far it had penetrated. It was completely saturated 12 inches from the end grain, and after that, there was only a small bit in the center that was not saturated.

I agree wholeheartedly that the surface film finishes that lay on the wood like a piece of tape will hold moisture in and cause rot.

My youngest grandson is a gifted soccer player. This last summer (2022) he attended the Liverpool FBC camp at Repton for a week. My wife and I flew with him from the US, then spent that week in Oxford.

We have traveled quite a bit in England, a fair bit in Scotland, and some in Ireland, but somehow missed Oxford. The week we spent in early July was wonderful. Walking the area was an education every day. What a treat.

We stayed in a VRBO flat in Crawley, above a Chinese take away, and rode the bus into Oxford. A highlight for me was looking out the bus window one morning and seeing you on a corner waiting to cross the road. I only wish I could have seen you at Blackwell’s on our visits there!

A very lovely and historic area, and we will have to visit there again.

Thank you for the education you provide for so many of us. You have a true gift as an educator, as well as your gift as a master craftsman.

just curious – is a ‘double’ or ‘quadruple’ mortise and tenon stronger/better in some way than a single large mortise and tenon? i would have thought a single big mortise and tenon would be easier to make, so curious why they went for double/ quadruple etc approach?

kind rgds

I guess you’d be taking a lot less material out of the stile, so it would have more integrity. I’m not sure they’d have put as much focus on glue surfaces in those days, maybe, maybe not, but the quadruple would give a lot more surface area for gluing and thus a stronger joint (as I say, that possibly wasn’t in their thinking, but we might consider it today). If you’ve ever tried a double tenon, it just feels stronger, almost like the wood is braided. I guess there is less lateral movement than might come about if the single tenon isn’t perfectly fit. I guess there is also the pride of the craftsman, and the fact that they were afforded the time to make something beautiful over something quick.

Too many guesses and assumptions here I think. No glue, just drawbore . . . Outdoor joints weren’t glued as this causes problems. The side by side tenons spans the greater width to keep the outer shoulders tight. So let’s skip your first two sentences. The twin and double tenons are stronger so don’t just feel stronger and it’s the retaining value of the wide shoulder that is the premium intent so the pulling and holding of the tenons is integral to the shoulder work. I doubt very much that pride entered into anything at all here. these men were different being out there bymthe hundreds of thousands they just worked and weren’t precious about their work. And lastly, no way were they “afforded the time to make something beautiful over something quick”. They had to make it right and quick all in the same economic movents throughout each 60-70 hour week and that was if they had a good master in charge of their work.

Hello Paul. Your last comment really struck a chord with me. I remember long ago as a young carpenter replacing chair rail at, coincidentally, a local university. A professor watching me through his open office door commented on how fulfilling and satisfying it must be to work by hand at such things. I smiled and told him it was, not wanting to ruin his romanticized notion, but knowing full well that time was money and I too had a master that I couldn’t work fast enough for in a system that sucks the life out of you if you let it. I think of that exchange often as it keeps things in perspective for me.

Indeed, keeping pieces together and ensuring correct geometry are two different functions.

drawbore/glue/tusk tenon/bed bolt/… for the first one, shoulder for the second (correct angle, squareness most of the time).

(correct tenon and mortise need to allow proper shoulder seating to avoid warping of the frame.)

To keep the two functions separated is generally good practice in metal assembly design but is seldom practical in woodworking

Interesting everyone. Thankyou

Having first attended the university and then worked as an architect in Oxford over the past 25 years or so I find perceptions of the buildings both interesting and enlightening. I think we sometimes forget about the custodial input of the Colleges along with the University as institutions. Maintenance is a continuous and ongoing project at considerable expense. Externally what we see erodes and degrades much like anything and a great deal of the facades we look at are fresh stone within the last 40 years – a brief scan of earliar photos will show the parlous state of much of the fabric prior to commencement. Likewise much internal replacement and careful restoration work takes place year on year. The dreaming spires are kept in tact by dint of considerable investment and the careful workmanship of contemporary craftsmen of not inconsiderable skill.

A reality check for sure but also affirming of a culture of stewardship. Thanks for that.

Paul, I am thankful I have found you and your lessons about woodworking, I am 78 years old and I needed an interest for my later years. Woodworking has become a passion I seek to learn. I want to strive to work with hand tools rather than power tools whenever possible. I ran across your comments about a spill plane. I would like to own one but as you know they are scarce as hen’s teeth and very costly. Have you made a youtube episode on how to make one or would you consider doing an episode on how to make a spill plane? Again thank you for your wisdom and willingness to share your life and woodworking skills with all of us.