Beware of Legalism . . .

. . . it can stymie your work!

There are so many things woodworking that are taken for granted and my posting the picture below on my Facebook with a short, almost invented conversation sparked off almost 3.7 million views in just four days with 2,000 comments and 440 shares too. The preconceptions people had and put forward by way of comments showed real prejudices people had that were most of them unfounded but some that should be considered but mainly not as serious as they thought or indeed were taught.

Many things did come out of the woodwork in the last four days or so, not the least of which was the limited and distorted views people have about certain things. Peer reviews can be very interesting and occasionally helpful as in our tunnel vision we can miss things that others see but the worst thing beyond being occasionally helpful is the level of true honesty when jealousness or envy raises an ugly head.

Here are some thoughts from my posting the single picture on my FB page four days ago. I will post them as questions rather than the vague and obscure statements they actually were. I think it is interesting to see people’s perspectives. here is the offending image:

Q: If you drive a steel screw into oak, or any other wood high in tannins, the acidity causes the screw to rust. True or false?

A: True: This can and does often happen but mostly if or when the oak is exposed to high levels of moisture in the wood and surrounding the screw be that from water as liquid, steam or local humidity in areas with high humidity. This can be in regions of countries, in homes and businesses and then in rain and so on.

Q: Should you never use steel screws in oak then?

A: You can use steel screws in oak just fine, craftsmen have done so forever, but you should consider where the piece you are making will stand in its final positioning. There are thousands upon thousands of oak doors here in the UK ranging from small entryway doors to massive 20-foot high entrances to colleges, universities, public buildings and offices six-foot wide hanging from steel hinges with every type of steel fastenings ranging from strap hinges, hasps and such held in place with steel bolts and lag bolts passing into and through the oak. They have been there for decades and even centuries. If it is an indoor cabinet or dining table, something like that, there should be no problem but bathrooms with steamy showers might be more questionable.

Comment FB Statement: If you drive steel screws into oak it will cause rust and the rust will split the oak

Q: Can rust cause wood like oak to split?

A: Not directly, no. And of course, rust will never cause oak to split. What can happen though is if the area around the screw is exposed to long-term moisture it can cause rust in the screw and this can adversely impact the wood causing some breakdown in the fibres directly around the screw. In any case, rust does not cause oak to split and neither will it any other wood. Poor workmanship, not drying the wood down to acceptable levels as in drying before use can allow wood to shrink further and the resistance of the screw can prevent tolerable movement in the wood resulting in a split. That’s why, in joinery, we generally get the moisture levels down to acceptable levels before we start the joinery. Expansion in joinery very very rarely causes an issue but shrinkage can and often does.

In dry conditions, and if the wood was indeed fully dried before the screws were imported to the wood, this is most unlikely to happen at all. In our historical past, wood was limited to air-dried levels usually under a cover or in a barn which still left high levels of residual moisture within the fibres of the wood. The general rule was to make it and watch it before selling to make sure once it was made no cracks arrived before it was sold. In good workshops, and we are talking from the 1600s on to the invention of properly controlled kilns, wood would be taken from the barns and under covers into a tighter and more controlled environment where heat in the general atmosphere was lowered by fires and heating. It wasn’t the equivalent of a kiln but better than from the barn. In vernacular furniture, wood was worked because they couldn’t get the moisture down any further. Today, our oak is dried down and can indeed be drawn down further through kiln drying and centrally heated climate control in buildings. `we do not face the same issues. Generally, oak is dried down to between 7-12% and this will pose no problems for us long term.

Screwing into end grain also figured high on the list, but mostly people made assumptions and statements instead of simply asking transparent questions.

Q: I see the screw goes into the end grain and I was always told never to do that because the screw has no holding power.

A: I think we all know that screwing woodscrews into end grain generally has less pull and retentive power but it’s not nor is it near no pulling power or retentive value. Experience has clearly proven to me that every wood is different with regards to ‘hold‘. It has also told me that screwing into end grain works well most of the time. Some woods do take a thread really well and give a thoroughly good bite whereas others can be pretty crumbly. In 99% of cases, end-grain screw hold will pull and hold just fine. It’s been done for at least a century and a half to date and it will continue to be done, otherwise, everyone needs to ditch their pocket-hole joinery which is not actually joinery.

With the development of the battery-driven drill-driver came excessive power many times greater than hand power to drive screws. At woodworking shows these days you’ll find a two-by-four with a hundred screws driven into it for customers to check out the latest Dewalt impact driver. Mostly it’s the macho-man thing, muscle flexing to try to stop the drill mid-drive then standing back in admiration. That’s not us. Drive with too much torque and there is no doubt that the wood will give in the end-grain part of the connection. On the other hand, we might find it impossible to drive the same 3″ screw with a hand screwdriver.

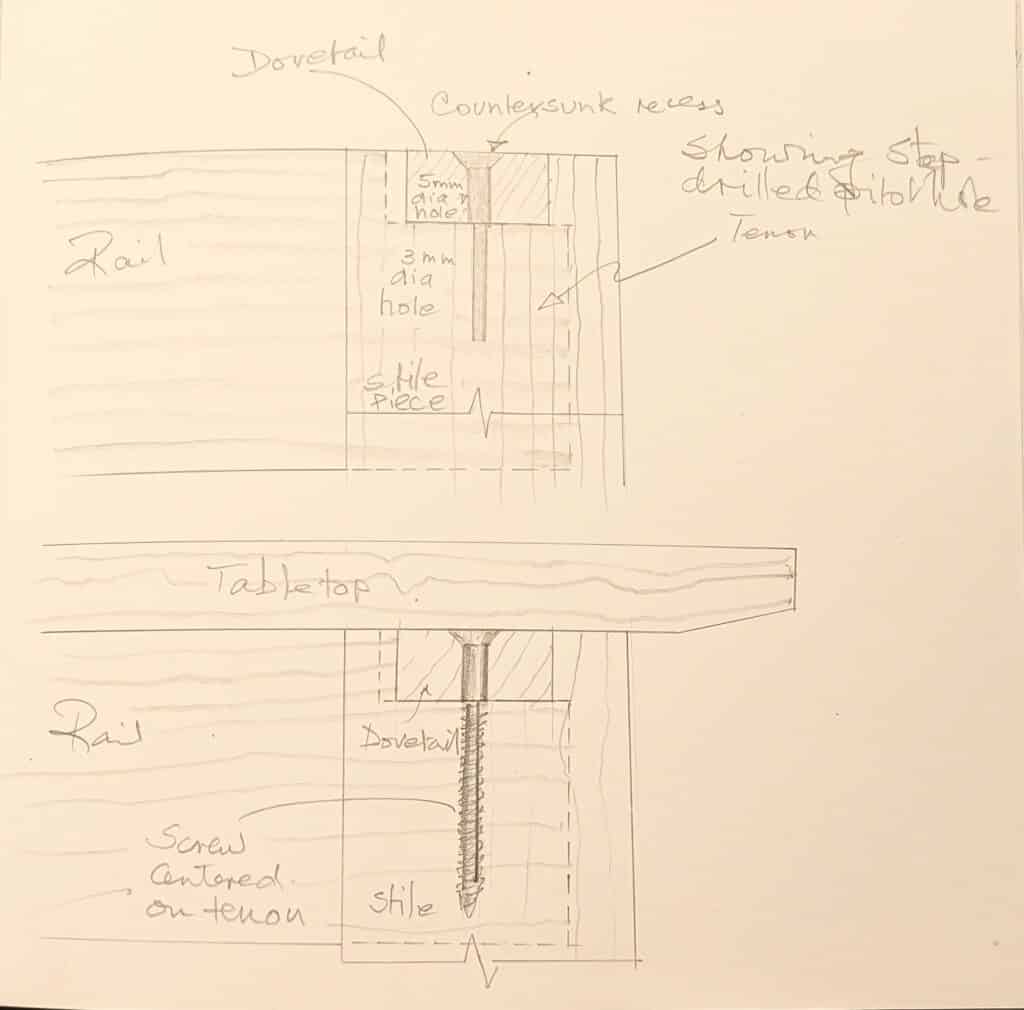

Unfortunately, we live in an age where the screw is developed to self-drill and countersink with supposedly no need to predrill and use pilot holes. On a deck or in stud walls in soft-grained, mushy wood this works well. It’s still crude but it is functional and fast and that’s what makes the money. I think that there was something of an assumption in the commenters on my FB post that I did this with the screw through the dovetail and then into the end grain. Had I indeed done that then I am sure it would have split and stripped out. And this is the fallacy in it all; they assumed I was just like them. The drawing below will show the strategy I always use. It’s one that never fails.

Of course, nothing reads never screw into end grain, as many said. It just means your reliance should be, well, slightly adjusted. In the case of the image, people made too many assumptions and I understand because I did lead it in that direction. I wondered how they would perceive such a concept, a perfectly made hand-cut dovetail with a screw driven through it to pull it together, and they proved many wrong theories have indeed taken deep root. They declared that the wood would split, cause weaknesses, take out too much wood and thereby make the joint substantially weaker, that the screw itself would split the wood and another half dozen issues that quite frankly were indeed inconsequential. In reality, not one of the concerns offered, and there were a couple of hundred, were true in much of anyway. That said, something somewhere had indeed informed them. By informed I mean formed-in or in-formed. Somehow the tannic acid in the wood was going to cause the screw to corrode at some alarming rate. Whereas tannic acid in oak is something of an issue, it’s only truly an issue where neglect and high levels of water surround the steel and the wood. Would I have used steel woodscrews in an oak project exposed to high levels of humidity? And by that I mean green oak or oak to be used outdoors. No, I wouldn’t. But then, as said, thinking of the hundreds, no, thousands of doors made from solid oak where the hinges are indeed bolted and screwed with steel fastenings to oak, I personally think it’s fine. Somehow we have gone overboard on the issue to the point that you should NEVER use steel screws in oak. That is what happens when we become offended. It leads mostly to unjust criticism often resulting in impractical silliness and of course, legalism; legalism has a way of hanging us up. Several offered the solution to be to use stainless steel screws. Though it is true, and we could do better by using stainless steel, I thought that was funny. It was the assumption that we have stainless steel screws of the exact type with the right head, screw thread length and diameter hanging around in boxes and that they would be available right there in the zone. That was just too much for me. I confess, I did laugh at that; quite a lot.

Now, that the screws will split the oak, split the dovetail, rust in the countersink and so on. We take steps to prevent such things. The first one is to use a pilot hole so that the screw hole is stepped down in size. The hole in the dovetail takes the full diameter of the screw and then countersunk at the same angle as the underside of the screw head. This seats the screw nicely. In the second, lower piece of wood receives the pilot hole that does more than just pilot the screw but receives the main body of the screw minus the threads so that the threads alone bite into the walls of the hole. really gives good grip and pulling power and the wood does not split. Also, the tight dovetail, the size of the screw diameter, etc disallows the remote possibility of the dovetail splitting.

Ugliness was cited. Well, that’s all in the eye of the beholder. The accepted phrase in all design is that “form follows function” is as good a precept to accept as any I know of as a designer-maker. Everyone assumed that the dovetail would be seen and clearly visible when the job was done and no one of the earlier commenters asked if it would indeed be visible. It won’t, but there are times when it could be and it would offer a practical solution that dovetails only really have unidirectional pull in resistance. Adding the screw adds omnidirectional resistance albeit perhaps less so than the dovetail itself.

The screw itself in its beginning was the product of a highly inventive mind and goes back to around 400 BC to Archytas of Tarentum (428 BC – 350 BC). In our world screws and screw threads have become highly sophisticated to cope with the demands of fast assembly and production in different industries. In our woodworking world, the diverse designs cater to deck screwing complex fasteners. We buy them by the boxful in every type of metal available for different applications and environments. Think of where we would be today if we had stopped back in 400 BC.

In practical terms, it often eliminates the need for any clamping beyond the simple pull of the screw itself. In adding cleats to the insides of cabinets for shelves and drawer runners where clamping might be impossible the screw and glue conclude the work. Screws can, of course, be temporary and removed once the glue cures or they can be temporary until the glue has cured and then just left in place with no particular detriment even long term. In my situation at the top, there really is no truly good reason to remove it. Additionally, I might offer that the screw gave a fully centralised pulling dynamic smack on where it was needed slap bang in the middle of the dovetail joint. No clamps in the way for hours and no waiting for me to be able to continue in my working on the project. I have done this in hidden dovetails for half a century and I was taught it and trained to do it by men almost old enough to live in a time when wood screws with international availability were still on their way. It’s not a ‘Paul-Sellers concept’! It’s been done ever since woodscrews were invented.

I was surprised by the number of opinions people had. I might say ‘mere’ opinions for they were little more than that and with no substantive support or evidence. Many if not most were literally based on what I see as completely erroneous assumptions with no validity in the concerns expressed and yet the commenters were so adamant that what they thought would happen would indeed happen and destroy my efforts. It’s really unfortunate that the quantity of them was so many; too many for a lone man to counter because they came in so fast. Worse still really was how endemic these biases were, and I think that that was very unfortunate. So many put faith in just about any kind of dowel as a viable alternative to the screw while others said that removing material for the screw was weakening the joint itself. They almost all of them were so blinded by what was mere opinion rather than fact that they really were unwilling to adopt any other perspective than their own. I realise that mostly the contributors were inexperienced but it soon became apparent that it was as if their brains had been, well, copied and pasted. Replacing wood with wood via a dowel offers zero pulling power but they didn’t see or understand that. What I needed was the initial pull to keep the dovetail in the recess so I could keep working on the project. They dismissed this altogether which really surprised me. The thing that struck me was what I saw as high levels of self-righteousness for what was honestly presented and then too how many wanted me to then “at least hide the screw behind a dowel.“, thinking that dishonesty to be the more honest way and, yes, the better thing.

I did what I did to show the brutalism of legalism and control. I and thousands beside me have done this for generations. All of the men in my apprenticeship days did it because they needed to continue working on the pieces and they couldn’t wait for the animal hide glue to harden up for hours. I cannot tell you how many dovetail joints I have come across since my apprenticeship days (58 years to date) that were nailed after the glue was applied and the tails set into the recess but it is many a hundred.

For clarity to the first post, I added this text to a second, follow-up post:

For those with a genuinely inquiring mind seeking true answers but following certain erroneous precepts, there are many things to consider from my last post. So I did something probably or possibly none of you did and that is take two pieces I knew the age of and withdrew the steel woodscrews.

The drop leaf table is 85 years old. All of the screws holding oak to oak and steel hinges to oak are done using steel screws. I removed the screws and only one of the two screws had a very mild powdery dusting of rust. This would have happened in any wood. Certainly, nothing that will change in the next 200 years. The other table, again oak, was made 13 years ago with steel screws into the oak to hold the turnbuttons. There is no sign of rust anywhere. According to the expert comments on the last post I should be experiencing severe degrade leading to black staining, splitting of the wood and fragmented fibres. Had I and the other maker listened to these people we might have been put off. I own dozens of handmade oak pieces and not one of them shows the slightest signs of rust.

I encourage you all to question the authority of those who informed you. Yes, I can produce pieces where tannic acid has caused the rust on screws and the resulting black staining on the oak, but in every one of these cases, water had always been evident and excessive.

The result of my post was highly successful I think, and I thank all of the genuine enquirers for their input.

Oh, I added the cabinet I am working on so you can indeed see the context. The tabletop will be added next, then the drawer and the door.

“They almost all of them were so blinded by what was mere opinion rather than fact that they really were unwilling to adopt any other perspective than their own.”

So true. Apart from that there is a lack of mind capabilities to accept, that indeed there is always another perspective. It makes a difference in life if you are curious to find these other perspectives and have the ability to judge the challenge from there. “To a hammer every problem looks like nail.” Being the person behind the hammer gives you the alternatives.

I’m saddened only because this seems to have caused you stress. I learned something valuable: Instead of leaving the project for a few hours after glue is poured, an occasional screw will allow me to keep working. What a valuable lesson for me! Thank you Paul.

Paul, your comments are greatly appreciated! There is nothing that can replace years of practical, real life experience!

I suppose some of the comments may stem from a different accepted methodology based on ‘current’

practices. As you stated Paul there is much apparent value placed in driving self drilling screws in with brute force. This is on the condition that the wood is suitable, speed is the requirement and the job is facilitated with no detriment to end product. I see the same approach with pneumatic nailers. When the wood is old and brittle, or very hard it is the height of folly to act on such a premise as damage or complete destruction of the material is almost certain. Pre drilling with countersink, clearance and pilot holes came about for good reason based in actual construction experience, irrespective of it being in joinery or carpentry. As you stated yourself, many a time where appropriate had you seen this method employed before. As always, the quality of hand joinery in the picture was very high, if the screw was employed inappropriately with no good reason then maybe some of the comments would be warranted (haven’t seen them as not on Facebook). I knew a much older carpenter who had transitioned to working in a hardware store and all the work he had done was with green hardwood stick framing and hand tools because that was what was there at the time and I asked him how did they judge the size of the nails for construction at the time. He simply stated that it was based on what could be driven in without destroying the timber or bending the nail through experience. Any repair work I have to do now on older houses with the thoroughly seasoned jarrah, karri and occasional wandoo has to be predrilled often with lubrication of the fixings to avoid seizing. Screws can make an excellent clamp and enable a job to be continued without delay. I can’t see anything to fault- its not as if the screw head is sticking out the front face or anything!

The perfect lines on that dovetail is mind blowing.

Thanks for such informative post

I agree – good enough for a show face.

I like this sentence: « When the student is ready, comes the master »

I did woodworking in a high school in France. The teaching was hard because the pupils were mainly not motivated. After two years there, diploma in pocket, I abandoned woodworking. However, for 15 years I thought of wood. I had tried to resume training with the companions of duty but I was already too old for them. I no longer had the right to receive their education and thus, to go around France. So ? I forgot.

One day when I was tinkering with a wooden planter, I found myself facing a difficulty, I could not rip cut a piece of wood effectively with my hand saw.

I went to different stores and asked this question: « why can’t I effectively rip cut with this saw ? » No answer, no one could answer me.

That’s when I’ve been looking online. No response in French but, a video in English of a gentleman, Paul Sellers.

Since then, Mr. Sellers, I have changed my life. I do woodworking, a modest work but, I always try to learn and, as a student would listen in martial arts are « Senseï », I listen to you, I listen to my master. there are other woodworkers who bring me interesting lessons. Robert Wearing, Sam Maloof for vision, freedom of form, Christopher Schwarz for the passion he puts in some of these books to tell everything again, and for the interest he takes in the furniture of necessity. Only, where I feel at home, where the gestures are so flexible and effortless that I learn just by looking, it is with you Paul and for that, thank you. Thank you for teaching me, thank you for asserting me, thank you for participating in the changes that are taking place in my life and, join me without knowing it, all those to whom I can show the can that I know and thus, help them to do DIY with hand tools from garage sale and with gestures, healthier, safer and rewarding.

Right now, I’m finishing the fly swatter you’re teaching, it will be a gift for my sister. My parents are always happy to receive a box, a spoon, a clock or sometimes a library shelf, a spice piece of furniture, a shelf … Your teaching makes me happy and, this happiness, like a wave on the water, spreads to everyone around me.

Not everyone may be ready to receive.

When the student is ready, comes the master.

With all my affection, Ludovic

This story from a student who truly follows your work, outweighs all 2000 FB comments from the nattering nabobs of negativism.

Hello Larry, I hope so, I hope so…

Hello Ludovic,

Other life, same story here. I would glady meet you. is it awkward to ask in what region do you live? (I’m French too)

Best Regards,

Vivien.

Hello Vivien, nice to meet you. Glad to read you. I live near Aix-en-Provence.

Cheers, Ludovic

Exactly as I would have liked to have said.

Paul, is the image I would like people to think of me.

Chuck W

Tampa, FL

Imagine that, an alert mind with experience based knowledge trumping conventional wisdom. And on social media no less. I guess anything’s possible!

Interesting article. I’m surprised no mentioned of the corrosion resistance of stainless and coated steels. I was wondering the reason for the screw. I assume since the dovetail will handle any tension longitudinal with the tail, the screw provided some needed help with perpendicular force, like pulling up when moving the piece. Another insightfull share of your knowledge. . . . thank you

I think you discovered the formula for viral posts. Start with a thumbnail that breaks the “rules” of woodworking, tell why it’s an exception, show your case studies (old furniture with no problems), and then summarize to debunk these erroneous precepts among a wide audience.

My two cents: Zinc plating, polymer coating, etc, does most of the work to prevent rust. Bare carbon steel will rust wherever it’s used…at least in Oklahoma.

Hi Paul,

very simple solution, stainless steel woodscrews. I’ve used only stainless screws in my Bee hives with the added benefit that I will be able to fumigate with acetic acid if needed. For use in treated wood on the ground they are even better, when the wood rots simply recover the “like new” screws and reuse them.

He references SS screws in the post…

Thank you Paul for another Master’s experience explanation.

Looking at your screw in a dovetail joint should have begged the simple question, what is the advantage of this screw used in the dovetail? And not to immediately criticize you or the technique. Having followed you for many years in every media form you have ever produced, I trust that you always do a certain technique for a valid woodworking reason based on your many decades of vast experience. It seems that nowadays people are looking to criticize the masters work first to make themselves look important, or more knowledgeable. Rather they should ask valid questions on what they see so that they can learn and improve their skills.

As for using stainless steel wood screws, it is my experience that pilot holes are definitely needed for them as they do not seem to have the same innate shearing strength as regular steel screws to the torque forces applied, especially with battery powered drivers. The screw heads will wring off in a flash with a powered driver. It is better to use a hand powered screwdriver

( turn screw) with SS screws into pre-drilled pilot holes, and not over tighten them to the point of breaking.

Cheers,

Michael USA

sadly michael if you are over 50 you are no longer relevant and obviously know nothing worth while.

Paul, your comments on legalism are spot on. It is a scourge on the planet and found in just about every discipline. Always disappointing when it rears its ugly head. I experienced the same type of thing when I sold off my table saw and thickness planer. The legalists were appalled, but I am happy. Your experience and observations are very welcomed to this amateur. Thank you!

I have seen several research articles that revealed that people who know the least about a subject are the most confident, and likely to be wrong, of their opinions. While people who are learning to master a subject are very aware that they have a lot to learn. But there comes a point where a lot of experience and knowledge gives the true master both the confidence and ability to teach others the art.

This article oozes with evidence that it comes from a true master.

It is unfortunate that so many run counter to thinking about things ‘inside the box.’ Sometimes it’s better to think ‘outside the box.’ Rules are simply guidelines for what might be the norm. There are always exceptions, no matter the field. Context plays a key role in any application. A single photo does not always tell the entire story. It should be cautionary for those whose minds are so quick to respond, to consider that a single picture does not tell the whole story. Despite the opinions of others who have no doubt been shaped by those from whom they learned, it seems this post offered yet another lesson in considering things are not always as they appear, much less than we might know. A dose of humility and acceptance that “I might not know all I think I know” seems in order. Great post.

Historically, during the much longer seasoning period, water soluble, tannins are likely to have been washed out, and thus much less likely to have been an issue.

During the online debate I mentioned an old oak vice I regularly use that has steel fittings with no staining. Part of our garden fence has some old oak posts (that came here as ships ballast). Not sure how old they are, probably at least 40 years! They do contain steel nails holding the panels and staples and vines holding wire supporting plants. There is no evidence of the dark staining or that the steel has rusted any worse than in other outdoor conditions. When we moved in 20 years ago the oak was very weather beaten, but it has outseen a new fence put in by a neighbour at the bottom of the garden (recently replaced), as has the larch fencing panels. The latter only needing the odd replacement nail.

Most of the people viewing your “screw” post only seemed to see the “offending” screw. If they had looked beyond it at the rest of the structure, it should have been obvious that some form of top was eventually be fitted. As was the tenon that the screw would pass through. A picture tells a story, but many only saw the screw.

I was reminded of how screws have changed recently. I had some old Nettleford 3″ x 8 Pozi screws left in a box that I bought 40 odd years ago. When I tried to drive them they would only go in about half way and I had to drill pilots, the rest of the screws that I was using were self drilling.

I do have a reasonable supply of stainless screws for use outdoors. Recently the range available has become much less and the price now makes me reluctant to use them.

Well done on the Facebook post Paul, I did enjoy seeing some of the comments.

this is why i have such a laugh watching most youtube videos. it is the ignorant leading the ignorant. as an example, it is now generally accepted in y/t that a jointer will give you snipe and there is nothing you can do about it. of course it is only about the lack of knowledge to set it up correctly. but one watches a video on set up by an amateur with no understanding, decides to make their version of the video with the same misconceptions etc etc and now the world believes that snipe is a normal part of jointing wood.

oh and as an aside, yes i think people forget that time is money in trying to make a living in woodwork. i used to make one off commission pieces as a solo venture (retired now), and yes i would do things like that so that i could continue to work. if i had to wait 4 hours from gluing up till i could continue, at the end of the day all i would accomplish and earn, would be a full bladder from drinking tea. unless the unit was completely stripped down it would never be seen.

I think that those who say that the screw would split the wood might be right if the dovetail was freestanding. But the dovetail is in the dovetail socket: where exactly would the wood move to if it split?

Today in these times of social media people have no respect for others, maybe because of their own short comings or their fat headedness. Paul you have many who

cherish your teaching’s, so don’t be bothered by the hater’s. One of my regrets is that I never got the chance to meet you, or take one of your classes while you lived in the states.

Are they hewing to low-tech purity?

Why else get mad about a screw?

rust occupies roughly 6 times the volume of steel. if confined it can exert a surprising amount of force. so it is possible that rusting screws could split the wood substrate but the conditions would have to be just right.

My professional background is structural engineering and I’ve done a lot of work in concrete. Rusting of steel reinforcing is a serious problem. The expanded steel material, tightly encased in the concrete, will indeed exert so much force on the BRITTLE concrete that the concrete will crack and split. Wood, however, is much more capable of absorbing those expansive forces by compressing of the wood fibers around the screw. Wood is much less brittle than concrete and its grain structure allows for movement as well. I believe that if a rusted screw appears to have caused a piece of wood to split, it’s not because of the rust. It’s because the screw was placed too near the end of the piece or some similar condition, which would have caused a split anyway.

Max- did you read the article? I think not. Really buddy, go back and with a clear unbiased mind…..read Paul’s article. The entire article. Don’t assume your response is valid, cuz it ain’t bro. The author is a valuable resource, and for FREE is trying to dispel misinformation slathered about. Really do your self a valuable educational act, and then we can communicate on a level playing field. Have a great day!

I am sorry, Max. Rust may increase in volume but not with strength. When rust increases to that degree it is always crumbly and can be rubbed away with the fingers. Whereas wood can rot as a result, that is not splitting.

I was amused by the third photo, the one showing the 80 year old vertical view of a hinge with one screw removed. Look at the recess into which the hinge was set. The lines were straight but there was a lot of distance around the hinge. No Paul Sellers tight knife edge fitting there! (;>)

I have been following your builds with eager anticipation for the next “part” to be posted. I have watched numerous times, builds from your Master Class and learned something new new I had missed from a previous viewing.

This post made me giggle in that I heard nothing about all the steel screws used attaching the curved slats on your bed build. I’m not a fan of exposed screws, and go to great lengths to hide them. If extra holding is required in end grain I sometimes insert a dowel horizontal to the screw and drill a pilot hole through it to gain additional holding.

I truly love watching you work and am building various items from your courses (albeit, not with the same perfection, but it gets better with each project) and have made great improvements due to your teaching. Please don’t let all the experts deter you in either the way you do things or in the way you teach. There is simple no other channel to gain the knowledge you are so willing to share nor the depth of instruction.

Dan

With over 50 years of experience in the fastener business I’ve watched the improvements of new plating types and methods. All of Paul’s points are valid and accurate. The plating type of the screw seems to be zinc dichromate which ii itself an anti rust plating. In the application of the screw 100 years from now the screw can be removed without rust and any type of electrolysis. Unplated screws haven’t been used for decades due mainly to demand in the market place. Even the thread pullout strength isn’t that much of a lose, less than 20%.

I have my grandfather’s oak roll top, well over 100 years, plenty of steel screws, no rust or splitting

Years ago I had the chance to meet Sam Maloof (who Ludovic Gatt mentioned in his comment above). My friend Ron Goldman (of Woodworker West magazine) took me to a showing of Sam’s work in WLA, CA. I had to chance to talk to Sam about his work, and asked him how he made such intricate joints work on his rocking chairs. He said, “drywall screws”. I’ve never forgotten that.

This is the quiet brilliance of Paul Sellers. How simply he turns this Facebook chaos into a crystalline teaching moment.

Along with “legalism”, another word that comes to my mind is dogmatism. It’s so easy to fall into a simplistic dogmatism when we think we’ve learned the ONE right way. Living in France, one of the things I enjoy very much is exploring the brocantes and studying the old furniture in them. These were pieces from 100-150 years ago that were made by craftspeople who couldn’t afford to waste time but who also took pride in their work. Look at an old armoire. The front of the panel will be planed to a lovely finish, perhaps with beading or some carefully applied molding. Then pull the drawers out and look at the backside of that same panel from inside. It will have been roughly planed only as much as absolutely needed to serve the purpose of assembling the piece. But the piece is as solid as a rock. Built to last, beautiful where it’s seen, and sturdy where it’s needed.

Rather amusing how those who know little are the loudest..

Nothing wrong with a sneaky screw or nail to hold a joint so work can continue.

This was taught to me by my Mentor, who would have been of the same vintage as Pauls Mentors, 30 plus years ago…

Fraid my mentors were nearly 60 years ago now. “Sneaky” is not really the word I would use. It was plain honest and out there for all to see.

I had never thought about not using screws in oak. Near my home is a world renowned organ repair company. They must have gotten one that could not be, or was not worth repairing. They put pieces of it out by the curb along with a sign saying free for the taking. I got some oak from that organ. There were a bunch of plain uncoated steel screws in that oak; none had any significant rust on them. I will reuse them some day.

I have used screws countless times just to hold something that become largely unnecessary after glue sets up, in most cases they are left with no consequences on strength or appearance. I have also hidden them behind dowels for aesthetics, but often worry more about that if there is shrinkage that effect integrity of connection at a later date. As far as the uproar regarding your usage there is always someone who like to knock people down because they think your not coloring in there prescribed lines be they real, arbitrary or imagined.

Oddly enough my first thought was actually

“What would be the reasoning behind Paul Sellers needing to screw a perfect fitting dovetail together?”

“Is there something I’ve missed or forgotten?”

It never entered into my mind to find fault or criticise, I’m was more intrigued than anything.

I almost guarantee every naysayer quoted what they learned from unqualified “woodworkers” on YouTube, such as a former odd jobs man who has built himself into the ultimate YouTube woodworking guru.

Ditto Jamie.

I got the post on email where I could only see the photo and first paragraph… my first thought was “What?!” followed by “Well, this will be good.”, poured myself a pint and my full attention – what a great click-bait.

I reckon besides all the misconceptions as m(d)isinformation justifying the thousands of negative comments, there is also this craving for “making a name for oneself debunking a specialist out there”. It is an unfortunate byproduct of the ease of free speech online (read two first paragraphs, make your own comment with little reflection), heck I myself fell into said trap. Luckily I wasn’t trying to say anything accusatory! 😳

Firstly, I looked at that very first photo (along with the ‘media response’ described), and it is with all respect I say:

“Paul, you punk!”

I think that’s a photo worth framing (oak wooden frame with non-galvanised screws) 😉

It upsets me, it confuses me and intrigues me …art.

Thanks to the subsequent article in turns into a point made, but the visual, signature all all 😆 what a beauty!

Ps: nowadays, why not using stainless screws for the rare unique occasions when rust is a worry? They are quite affordable

And now, that I finish reading the article (should’ve done before commenting, silly me), I laugh at myself and my stainless PS.

I really should listen/read twice and talk once.

Not a professional woodworker by any means but at what point do we take ownership for the care and maintenance of our own things? Good grief if something lasts decades good on you. Well done. Nothing lasts forever. Do your best, take pride in your work, and move on.

I think we live in a present age where those taking a day to cut a dovetail compare themselves to men in ages past cut dovetails for six drawers in the same time and because theirs might, and I say might reservedly, look a tad better feel that their one dovetail in the day’s work trumps that of the ancients under pressure because they knew there were ten men at the door waiting to replace them if they were too slow or a bit rough. I would not trust woodworking magazines for info on fine woodworking these days as it has become so very distorted. Dovetails should really come straight from the saw and only practice gives you this. When it happens, you own it.

I have read comments from people who took offense of Sam Maloof because he dared to use screws in his beautiful chairs. I’m pretty sure he knew what he was doing. It served his purpose. I’m pretty sure Paul Sellers also knows what he is doing. I plan to continue watching and learning.

Thank you Paul.

Truth is his screws, like mine, were temporary clamps he never took out cos he didn’t need to cos like me he knew there was no danger from the screws.

Hello, my cabinetmaker grandfather used to coat his screws with soap. This method had several advantages, firstly the soap drying created a thread and secondly insulated the screw from the wood.

The tannin of the wood creates with the screw what is called a pile by oxidation-reduction, also by isolating the wood from the iron this cannot be created.

It is true that the method of installation is quite long: you have to make the pilot holes then insert the screw coated with soap in force, then some time later remove the screw to finish drying the soap to finally put the screw back in place. The screw thread thus created makes it possible to remove and replace the screw to disassemble then reassemble the piece of furniture as many times as you want.

The reaction between lye (often referred to as caustic soda as well as sodium hydroxide) and animal fat is termed saponification which transforms the two substances in their entirety to become soap. Once cured over a period of days the lye becomes less caustic but the amazing thing is this. We are left with naturally occurring glycerine and glycerine is of course, the non-toxic ingredient used to soften our skin. It’s this that created a barrier to the steel and tannins so we would get a natural resistance where and when and if needed.

I might argue the term, “quite long”. It’s fractions of a minute really.

Somebody one taught me that if what he experienced contradicted what I argued then it is my argument, not his experience, that is flawed.

I think the most succinct and powerful summation of your message in this post is the fact that the phrase from your image caption, “controversial wood screw,” even exists in a conversation about furniture. How ridiculous is the concept of a controversial wood screw?

I’ve always felt that the difference between a craftsman and an artist is, in part, the introduction of the concepts of utility and efficiency into the equation. A screw serves a purpose and when it’s added by someone with the knowledge and skill you have, the rest of us would do well to pause and consider the reasoning and application. Not that you are infallible, but pausing and considering the work and thought behind a more experienced person’s work is rarely a mistake.

Paul,

Excellent post, as usual. About to reread to better absord your thoughts, reasoning. My question is do you ever use screw lube (several brands available)? I have found when placing hinges, predrilling etc., that a dip in the “lube” facilitates setting the screw, by hand of course. Thank you.

Brad

Not as such but I always use soft furniture wax after predrilling the pilot and stepped holes where needed. Probably would not go out and buy a specific product as everyone I ever knew in woodworking just used paste wax.

As a fellow woodworker all I have to say is look closely folks this is the work of a master craftsman the joints are pristine , and I envy all of Paul’s work, the skill it takes to produce this level of woodwork especially with oak is second to none, I don’t care about the damn screw.

This was a great blog! I’ve noticed this as well, and as an amateur, largely self-taught (or at least relying on my interpretation of helpful videos like Paul’s) to learn, it is quite confusing when you hear so many “rules”. As an example from another area of wood-based hobbies, on one Facebook Woodcarving site, a user helpfully shared his mistake of cutting himself as an attempt to inform others, and I was surprised at the level of vitriolic judgment on both sides – “only a fool never wears a carving glove” or “you shouldn’t use carving gloves because you should know your tools better”. I’d like to say most of these folks were inexperienced or had the arrogance of youth, but it was largely the opposite unfortunately. My attitude is if it’s functional and aesthetically pleasing for what I need, it’s good to go. Perhaps I’m sacrificing a few years of use off of a product that will be used for 10, 15, 20 years, but I have to worry about what I’m doing now, not one of the potential scenarios that may come to pass if x, y, and z aligned far in the future.

I hope that cabinet you’re working on will be a Master Class project — it’s beautiful!

It is indeed.

Did you not see that clean dove tail in oak? Yikes, get over yourself.

Mr. Sellers, as always, pristine workmanship of an extremely skilled craftsman, mentor, and teacher.

Thank you for the encouragement you offer in each video and blog you post. Thank you for sparking my interest in hand tool wood working.

Dear Paul, the ill informed an ill motivated quibbles must be exasperating. Few would have the patience and grace to address them as you have, informatively and not too testily. May you sally forth , emboldened by the support of your many admirers.

Also stared at email pic, and my brain went, ‘Huh?’

Then, ‘I’ll bet it’s covered (Phillips head screw).’

Then, ‘I’ll bet it’s for clamping — cool idea!’

Then, finally, ‘Shame to cover up such a beautiful joint.’

Brain got there eventually, even if it went through a few somersaults.

In my youth I helped build wooden boats. We used bronze screws, as they wouldn’t rust. Did this Urban Legend about not using steel screws get its start because steel screws should most certainly NOT be used in a salt water marine environment?

Paul,

You have long advocated taking apart an old piece of furniture to investigate how it was made. whilst dismantling a wardrobe I found screwed dovetails that were obviously used as ‘instant glue’