Plane-ability

Until you do it you won’t understand and it won’t be because you don’t want to understand or even accept it, it’s because you simply can’t. It’s not unlike using a chisel sharpened to say 250-grit for years on the old India Stones and then being given a chisel sharpened through a series of abrasives like diamonds (my very favourites) and on up to buffing compound at around 12,000-15,000. One takes a hundred times more effort to cut the wood and that lack of true sharpness is then reflected in the surface you just cut into. Your first thought could be a full rejection of what’s being told to you. But then when you actually feel the difference as you push the tool into the wood followed by seeing the outcome––you become a believer. But, sometimes, fairly often, I do sharpen to that lesser level and it’s not because of laziness or procrastination, I did it just yesterday; 250-grit and back to scrubbing off excesses before sharpening to finer levels for the final surface finish is something I do. But I’m not talking about sharpness here: the plane options as in choosing all metal over wooden ones, might be dismissed because one is ‘old’ technology and therefore considered out of date or outdated. We might think something to be more archaic than in any way useful to us when the alternative could offer us truly viable options for improved performance, easier working and much more. I want to talk a little about how planes will feel different and how if we went back in time a hundred years and more, we would better understand why crafting artisans in woodworking were indeed so very stubborn about keeping their wooden planes instead of accepting the more modern versions in cast metal. Certainly, there were metal planes available and craftsmen liked them well enough to use them for decades as is evidenced by the patina on them. I would like to change the word ‘stubborn‘ to ‘determined’. Old craftsman woodworkers were determined not to give up something that was better for something they considered less comfortable for them to work with. If you, like most, consider people who won’t give up working with wooden planes, and we are talking about a lot of modern-day users here, you might do so for the wrong reasons. Wooden planes are far from inferior and might well still be superior though you will be hard to convert if you have never mastered the use of one. This is usually the point when terms like Luddite are applied to people supposedly rejecting new technologies when it is actually done to deprive people of true realities. Here’s an example: “Our thicker irons eliminate chatter!” when the thinner irons never chattered in the first place.

Experience tells me different things. Mostly I believe that it is not necessarily an either-or and that we might enjoy the benefits of finding space in our work for both and all. Do modern planes of the all-metal kind keep their edges better, feel easier on the wood and in the hand? Well, that depends on a few things not the least of which is our attitude. Are we receptive to some old and ancient things like tools, technologies, techniques and methods being as good as if not better than new, for instance? Or are we simply dismissive? Of course, that works in reverse too. We can reject the new because we are, well, just set in our ways. But many times when people were reluctant to change it wasn’t a rejection of something new so much as shifts that altered a way of life. Here is an example to chew on: The mass production of growing raw materials demands a means to produce fabrics faster and more cheaply. This led to our discarding of good clothing before it was worn out and then slave labour to produce such things. I know, it’s a bit simplistic. Or is it? Look at all of the now so-called global issues surrounding just the one pair of jeans you are wearing.

Experience in using both wooden and all-metal planes over extended periods is likely to reeducate us if indeed we just give it the time it takes to adopt, understand them and get used to using them. That can be expensive in time, money and owning the tools to practice with.

My wooden versions feel wonderful to use and especially is that so on some particular woods. Ninety-nine point nine per cent of British-made wooden planes are made from solid, air-dried beech and of course, air-drying gave the most stable beech wood for planes. vastly superior to kiln dried wood every time. Beech of the vintage kind is amazingly resilient to wear, has tight interlocking grain and is extremely stable.

The British wooden planes I currently own all have laminated steel cutting irons that have good edge retention and take a keen edge too. Just as good and equal to any modern versions I have ever used. I think that this might well be because they were hammer-forged under the heavy tonnage of trip hammers rather than just rolled steel. I might dare to suggest that they are at the very least equal to any named cutting iron you care to name including those made by the so-called premium plane makers and they keep going over an extended period. The Mathieson one I am using above and my Marples ones all just keep going. Aside from that though, those who do believe we’ve truly bettered the bench planes with all metal ones usually say such things in ignorance rather than experientially. Even though it is slightly possible that they used a half-decent wooden one it’s most likely that they never put enough into it to match their skill levels to the masters that owned and used the wooden planes. Gaining mastery in using any hand plane as the ancients in our craft did takes time and most people these days are time-poor so I understand the reticence to try something just for the sake of it. You don’t just pick up a wooden, UK-designed 18th-century beech plane after relying on all-metal ones and own the experience. These old masters truly mastered the working of them. They sharpened and reset them with incredible speed, using the bench itself to nudge the cutting iron in and out for depth of cut and then tapping the plane or iron for sideways for lateral alignment in split seconds as they went on with their planing tasks. No matter how good you are with an all-metal version, mastering wooden ones of the British type (which includes those in the US with a few slight modifications) takes time but once you have it the methods belong to you and so too the joys of using them. Woodworkers may be free to give a negative opinion on using wooden planes as some kind of entitlement but it’s really only worth anything if indeed it is based on fact.

If you have never mastered handling the large wooden bench planes preferred by all British woodworkers for two centuries then you are unlikely to understand them as fully as they need to be to work them well. That being so, I understand the belief that in the plane’s evolutionary process, things can only be bettered. The reality says differently. Also, you cannot, cannot master the use of them in a matter of a single try so a true comparison would only be valid if you have invested yourself to some level of acceptable mastery in real-life working day in day out; something most could never do because of time or a lack of interest. You must have mastered setting and adjusting them to a high level of truly efficient mastery. It’s very doubtful that you will know such a one if you live in countries that used British-type bench planes that had much greater bulk than other European and Asian wooden bench planes.

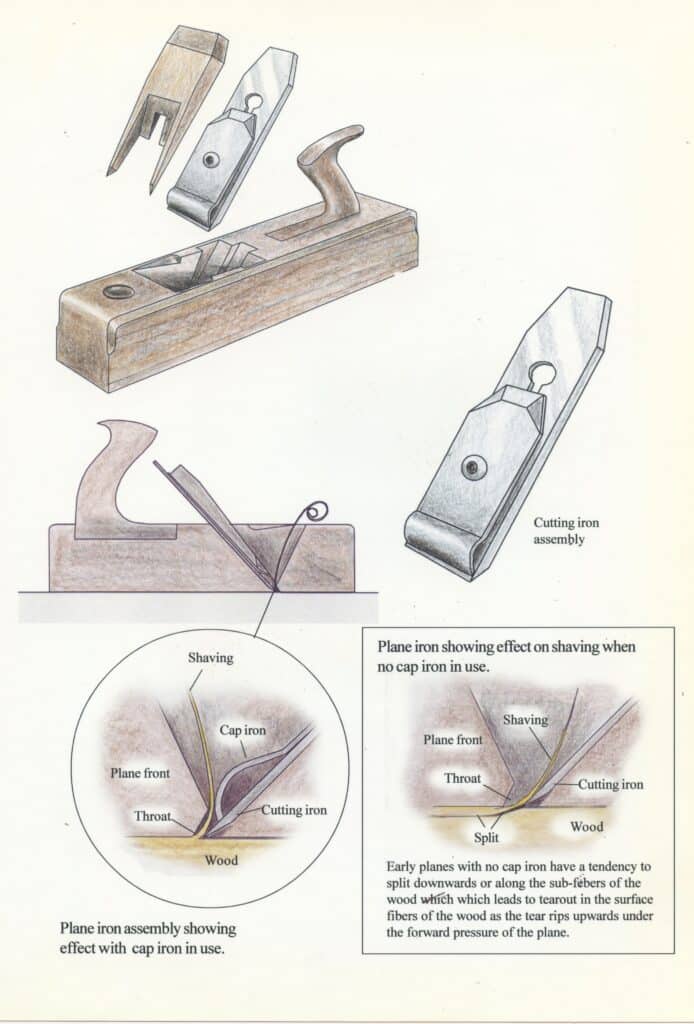

This is my best offering of the difference. Wooden scrub planes had no such name and neither were they created as such but the action of “scrubbing off” was so named as the act and art of using one. Well-worn short-soled planes continued in use after the soles were worn down half an inch in height and therefore had a wider and more open mouth or throat which meant that surfaces left after the planing were less refined or even somewhat torn. That increased gap allowed the wood to rise into the through before it was cut and parted away by the cutting edge hence the tearing or ripping of the shaving from the main body of wood. In scrub planes, the user cambered or rounded irons which made the planes easier in the cut. This left gentle undulations along the planed surfaces. You will often see this as a finished level of planing on unseen surfaces like the undersides of drawer bottoms and the back panels of case pieces, tabletops and so on. This was perfectly acceptable in vintage woodwork where the economy of time was more critical; passing wood through a power planer or a drum sander takes but a minute compared to half an hour with a bench plane. These planes started out with mouth openings of between 1/32″ to 1/16″ between the cutting edge and the fore part of the plane sole. After a few short decades of use, the plane’s sole wore down causing the gap in the mouth opening to increase. Reaching an opening of 1/4″ to 3/8″, you see above how this then allowed for thick shavings to pass through the mouth in quick succession. Though these planes still took decent shavings, they were usually repurposed for roughing (scrubbing) off and roughing down, which they did more capably and more rapidly than any all-metal woodworking plane designed to that end can. The shortness of sole enabled intense localised planing work which relied on the crafting artisan’s skill and ability to work the surface as level as possible by eye alone but in preparation for subsequent planing with longer planes like Jack and Try planes.

Jack planes also wore down in somewhat equal measure to the shorter smoothing plane cousins through continuous and consistent work. The mouths of any well-worn planes often had patched-in sections with a recessed piece of hardwood to close off the throat again. This extended the life of a highly valued tool for a few more years. Of course, the plane soles continued to wear away stroke on stroke and over the decades, depending on use, became too worn to use as truing planes so these too became longer roughing down (scrub version) planes with the more open throat allowing for deep cuts and hogging off of masses of thick shavings at speed. In wood, the planes never felt crude, cumbersome or awkward, which might seem surprising. In use, on wood, whether as a scrub plane or a fine refining surface plane, the wooden planes glide supremely. Think cruise liner on still waters coming into harbour here.

The longer Try planes wore down much less than the short-soled smoothing or Jack plane versions simply because the early use of these two starter planes reduced the impact on long planes. That said, in the hands of a skilled woodworker, the try planes are actually minimally needed if at all. I rely on Jack planes for 95% of my truing longer work anyway, even for long edges. Though all of the wooden planes might seem or feel heavy and unwieldy in the hand and arm, you soon get used to them and in most cases, a wooden Jack plane is about 20% lighter in weight than the standard Syanley versions and almost 50% lighter than the premium heavyweights makers seem more wont to make. Persevere if you are indeed new to them; on the wood, they respond very differently and once mastered they are very enjoyable to use. No matter the wood type or the state of the surface, on the wood they suddenly feel utterly lightweight, almost as if they are not there. This might seem an exaggeration but I assure you it’s not. Wood on wood in planing mode, you will be stunned by how easily it glides over the surface. What slows it down to sluggish levels, as with all planes, is a dull cutting iron and too deep a cut. Being pushed over the surface of some softer-grained woods, pine, fir, poplar soft maple and many hardwoods with softer grain too, this plane can hardly be felt despite the fact that wooden planes of such mass compare very closely to their all-metal counterparts of the 19th and 20th centuries in weight. Even waxing or oiling the soles of metal planes will in no way be comparable to wood on wood. They may be similar in weight, but on the wood somehow all of that weight on wooden planes just disappeared. Not so with metal planes and that’s what makes the difference.

Be careful about workbench heights. The heights of workbenches some people might consider more practical and standard at lower levels might well be more tosh than practical for we hand toolists creating joints, planing and sawing wood and all of the other elements of hand tool work. And if indeed you are not using hand tools then what might seem logical can indeed be highly illogical. Telling you you need to place your upper body over the plane and the planing work to make the plane work is not really helpful. What would likely be more helpful would be to say you need to keep up with your plane sharpening and that alone will do far more to pull the plane to the work than having to increase unnecessary pressure and friction to the wood to smooth and level your wood. Ninety-five per cent of poor planing results come from procrastination in sharpening the plane. I am likely to sharpen any plane four or five times per hour of plane work at least.

Wherever and whenever possible, a bench height needs to be custom fitted to the individual first and then too to the type of work they might be more involved in. My work is a combination of surface planing, sawing and joinery of all types along with assembling the units. As Mr average height of 5′ 10 1/2″ (1.8m) the work I do is consistent. My bench height has been 38″ for almost six decades. I have never had back issues and still, at age almost 73 nearing 74, I have no aches in my body anywhere. A machinist on the other hand is more likely to be assembling components made by the machine so, yes, as more of an assembly bench not used or much needed for hand tool work they might need a lower work height than a hand tool workbench.

Sometimes, often, we can assume that we are further along a pathway than we actually are. That somehow we put some distance between the old and the new and the new is always better. We might even speak from this supposed vantage point yet be quite wrong. If we skip a generation or two of the ancient makers and users and then the not-so-ancient in anything, we will naturally assume something better came along. And then books get written too stating this or that and before we know it the assumption of being right becomes the fact. We then quote the fact and the quote becomes well-known and, well, right. I can think of a dozen examples and have tried to remedy the untruths of things as they came up. I actually wrote ‘think’ in place of assume in that first sentence of this paragraph and changed it to assume because it’s doubtful people will actually even think or give a second thought to it. I think this to be an important point.

As an afterthought, the average Britain in the 1700s was supposedly three inches less in height than today. A lower bench height of 34-35″ would have better-suited workers of that day. This video will help you to understand the synchrony between planing and bench heights.

There have been pivotal points in my life where I have experienced a feeling even though nothing touched me and I touched nothing. I recall the day I first queried what was being said online and in magazines about things and realised that what was said was completely erroneous yet was so very instant. Take BedRock planes, as an instance, or workbench heights needing to be ultra-low for planing and such. What about laying planes on their sides or Japanese saws being better than Western saws? All just more tosh. You can make anything work and make anything you say fact if it just suits you. The BedRock frog supposedly being vastly superior to the Bailey-pattern frog in Stanley planes is as good an example as any: it is decidedly untrue. My experience told me something completely different and for many good reasons. I knew the truth of it because I never reached for any of these so-called “Superior” or “Premium” planes even though I owned several of them. Back twelve or so years ago I spoke of the superior qualities of the better steels used and also the more advanced engineering, the crisp bevels to every corner and the flawless uptake of the screw threads and such. Since then I have changed my mind. I have found that I sharpen brittle steels more frequently and with more difficulty but not because they dull so much but that they seem more apt to edge fracture when I use them in the reality of planing woods with the occasional hard knots like you get in most woods in the day to day. I very much prefer that small degree of flex and tolerance I get from the older lesser planes too; a bit more give and take perhaps.

I have personally found my owning several of these more modern planes with tight tolerances is of little if any advantage. In fact, dare I say, of no real advantage at all. Once aligned and arrayed there on the shelf alongside my very basic, non-retrofitted Stanley #4 versions with their original cutting irons, I found myself never reaching for the premium versions again but always reaching for my Stanleys or, secondly, my Records. I am still on the first-ever plane I bought in ’65 and I’m on my fifth cutting iron. Why did I no longer ever reach for the Lie Nielsen, Clifton, Juuma, Quang Sheng, Woodriver or whatever other knock-off version smoothing plane for my daily use? Why are they now stored in plastic boxes and why am I currently considering a garage sale of all of my excesses to include these as being for sale sooner rather than later? Well, I just changed to using the ‘the’ before each one of them from ‘my’ to ‘the’ because they never actually felt as though they were as much a ‘belonging mine’ as they were the makers. My Stanley (along with others) became mine through the adopting of them through weeks, months and decades of using them. It didn’t happen overnight it took five years before I truly owned my first Stanley #4 smoothing plane from the 1960s. And then I owned three of them even more a few short years back when I replaced the handles with those I made from Yew.

I conclude now that my adopting and enjoyment of using and advocating the British-type wooden bench planes have absolutely nothing to do with nostalgia or antiquity, a stubborn refusal to go with the times or any such thing. It has to do purely with functionality. I think if I put one of my wooden planes in your hands and set you up at my bench you would see exactly what I mean. Once you understand how to adjust them, the speed in experienced hands equals that of those with the adjustment mechanisms on any of the modern metal-cast planes. The men I worked with as an apprentice adjusted their planes after sharpening in a matter of seconds. During use, they could bump the heel of the plane to withdraw the cutting iron by a thousandth or bump the toe to reset it by the same thou’ of an inch and get on with the job of planing. This was done on the end of the bench or the side of the vise. I know, we dismiss them because this sounds, well, too crude. But you must remember these planes survived through a 200-year span of woodworking history and more, a period when some of the finest and most creative woodworking of any kind existed. Infil planes with cast metal soles and sides came into being but were less used by most woodworkers than the all-wood versions because of weight, cost, high friction and so on. They never went longer than a Jack plane because the weight would have been impossible for most men. That too tells you something. Also, it’s well worth remembering that all metal planes distort in exchanges of temperature. Rarely do they remain true and flat and straight.

Furniture makers and joiners bought the castings alone and made their own infil for the plane totes and infil areas from scraps of hardwood be that oak, rosewood, ebony or fruitwoods like apple and pear. Even so, these planes still stuck like glue to the surface of wood being planed and really did need a wax candle applied to the sole to allow them a freer passage. Other infil planes were professionally ‘stuffed’ and many makers came into being to supply a ready-made, ready-to-go version. Norris was one of the most popular makers and these planes had full adjustment mechanisms that set the depth of cut along with an alignment lever, often all in one, to ensure the blade had parallelity with the plane’s sole and depth of cut adjustability.

The wooden planes were the ones 99% of woodworking craftsmen could reach for. And neither should we forget that it took almost 60 years for Stanley to finally succeed in getting woodworkers to adopt the all-metal Stanley ones. Stanley couldn’t persuade the artisans to make the change, they just never did get them to change: they simply died off over a six-decade period of transitioning when hand planing anything was being taken over by more efficient machining and so was dying off at a rapid rate too. Machines were taking over woodworking at an alarming speed and the wooden planes became obsolete because the makers were dying off and such tools were needed less and less. They were never abandoned because they didn’t work and work exceptionally well but because they didn’t keep pace with mass manufacturing and they were needed less and less, as were skilled artisans too.

So what is it with those of us still clinging to the hand tools and the methods of using them? Why not just get access somehow to machines? For me, this is where the rubber hits the road. Someone commented recently that most of my viewers relied on hand tools and that it made no sense to rip-cut thick oak using a handsaw. It was of course a strawman baited with hooks simply because no one has ever said to do so in my blogs or social media. I ripcut and crosscut oak and other hardwoods and softwoods every day and I do so using both hand tools and a medium-sized 16″ bandsaw. I am an advocate of bandsaws because these machines take such a small footprint and they are for me the most versatile of saws used for ripcutting wood. My garage workshop only has about three square metres of free workshop open space for me to work in. One tablesaw or planer would take up all of my space if I introduced one for me to use. But even that is not a good reason not to own one. No, not at all. I simply like hand tool woodworking for a series of really good and justifiable reasons more than owning a mere convenience. I need to give no account to anyone for my preferences.

Sometimes, and you might need to think about this –– consider it. In my world, for a lifetime of daily, all-day making week-on-week and year-on-year, woodworking has had perhaps a different and dare I say more profound realness to it as a class of working manually. Looking at it from this background will automatically translate things differently in that I am not from an academic place nor a desk job. I never attended university and college was something of a more sad joke. Most of my progressive education came at the workbench with a man named George who took me under his wing to teach and train me. When I began here in England, we that did such work, wearing overalls or aprons, boots to work in and with our hands for a living, would be regarded as something called, well, working class, manual labourers rather than as pastimers, amateurs, hobbyists and such. Of course, our modern-day versions would never use such terms and they no longer look as we did, they dress differently and approach work differently too. Today’s such versions are Influencers, Bloggers, Vloggers, Instagramers and so much more but perhaps less too. There is nothing so, well, ordinary about makers of this upper echelon. That I have wanted to persuade others to adopt elements of it where possible changed my way of seeing my worklife. I express what I know as truthfully as possible. I want to give everything without dragging things out. I recall a conversation with the then Fine Woodworking editor (USA woodworking mag) who wanted me to write for them. In the conversation, he said, “No. We don’t want whole articles. We want to keep our subscribers coming back. Make them short, in parts.” Naah! I thought. So I never did write for them or any other mag after that. Some woodworkers express things from their own background not as makers as such but as online presenters. By ‘as makers’ I don’t mean they don’t make but that they make on a more limited basis and purely to gain followers and subscribers. They never made to sell their work for a living as an employee full time or a self-employed maker selling their work to the public. This makes a big difference to both those watching and then too in their presenting. It’s just different. Hence the gladiator poses holding power routers and skilsaws. Dramatic posturing and a catchphrase strapped across the keyframe. Not too real.

I have seen how entities in woodworking promotional venues achieve different things. The tablesaw blade salesman takes a bar of soap to the saw blade before demos and after the cut hands over the offcut and the feel is silky smooth. Some in the areas I am more involved with spend quite some time tweaking their premium planes for optimal performance every twenty minutes so when a potential customer tries it out on some curly maple it cannot fail to impress. Of course, curly maple is a very nice wood to hand plane. This is all reasonable. The cutting edge and blade alignment, depth of cut, etc make a huge difference to trialing a plane. Obviously, spending time sharpening a cutting edge, perhaps as long as 10-20 minutes, gives the plane the edge it needs but in my world, it is just a bit unreal somehow. As a maker, I just sharpen in a minute or two, reload and get back to work. In my world, their world would be a luxury and would never be very practical, no way. And perhaps this is why so many full-time woodworkers working with machines say you can in no way make a living using hand tools (My previous article I just finalised and posted shows something very different). Anyway, having then loaded the cutting iron assembly, taking a similarly long period and setting everything before they present the plane to a pristine, straight and trued-up piece of hardwood that’s straight-grained and knot-free, they whisk off “onion-skin shavings.” as though this is the goal of planing wood. Maple, cherry, oak, ash, beech and a few others would all be good examples of wood too. Bracing themselves heavily they then lean into the already planed piece of wood 18″ long and a full-width onion skin shaving ripples from the plane. As the plane emits the shaving they stretch it part way through the stroke as the work is concluded. This act alone is completely unnatural but it’s done with a purpose in mind. It looks very controlled, easy. This is how you sell planes, cutting irons, sharpening stones, honing fluids, workshop classes, workbenches, vises, bench dogging systems, clamps and much more. The observer, never experiencing such magnetising results is immediately mesmerised by the desire they have to achieve this kind of result from a bench plane. Whatever is for sale in that particular place or at that time is the magic bullet needed to make a sale and make you the better woodworker. The promises are in the instance of success. It’s not unlike the promise of instant weight loss from this or that diet, really.

The problem, of course, is that we are new to woodworking with hand tools. We rarely have pristine wood, the perfected sharpening, any experience and so on. It’s more likely that we actually have sections of wood that in some way form a kind of frame, perhaps a box or other such sub-unit that has contrary intersections of wood in slightly different levels that defy uni-directional planing. And then too we have grain that’s totally contrary and no matter which way the plane is pointed it’s often or even always against the grain. So why am I saying all of this? Well, sensationalism sells as do smart-alecky postures and sayings. These mostly substitute for the reality that real woodworking mastery is totally interesting in and of itself. It does not need hype and hyperbole to make it work. The attention-grabbing has proliferated with partial strap lines with hooks to them. Few sites are free from promotions, sponsorships, free products and so on given to the various platforms to work as sales pitches somewhere in the deal. I want my work to be real, honest and uncompromised.

Thanks Paul. I have a few wooden planes. Lately I transitioned from premium planes to vintage metal ones. I plan to use these for a year or two then I plan to transition to all wooden ones (haven’t decided if they will be the transitional or tap the iron kind). Just want to get the experience directly.

What would be kind of fun would be to watch you make a project for your Seller’s home using all wooden planes. I know it can be done. It might influence folks to go out and purchase one or two vintages ones and give them a go; similar to how you brough back the router hand plane into popular use.

The issue with the planes and the reason I generally stick to my Stanleys is because these are readily available at quite low cost for those learning and following on a budget. I certainly do not want to send everyone out to try or buy wooden planes to work with because they are learning with me. I do want people to rethink and perhaps understand the the owners of wooden planes in times past were struggling to change because of issues inherent in the all metal versions which we have mostly and simply got used to but usually because we have nothing to compare them to without buying one.

Hi Paul,

That makes sense. Thanks for the response.

Sincerely,

Joe

Here in Belgium, one can easily find wooden plane for a few Eur on flea markets.

I have a few ones of various dimensions.

I don’t go very often to flea markets but I have only seen a half stanley look alike metal plane until now (lever cap and iron assembly missing!).

in NL you have the same, a lot of voorloper, blokschaaf, etc in wood, but also quite a few nooitgedacht and old stanleys on maarktplaats.

Your comments on premium planes and workbench heights are thought-provoking and may elicit a defensive response. Speaking of workbench heights, I built my English-style workbench to a height of 31 inches, and after using it for several years, I’ve noticed an improvement in my planing and sawing. I experience less arm fatigue while planing, but whether this improvement is due to the bench height or practice over time is debatable. However, I have noticed that my back and neck pain have increased exponentially to the point where I struggle with daily tasks. Since this condition is pre-existing, the bench height may be contributing more to this pain than it would otherwise.

As I mentioned earlier, your posts are highly thought-provoking for woodworkers, tool makers, authors, and magazines that have echoed each other for the past 70 years. Personally, I find them intriguing because they challenge everything I’ve learned from books and magazines about premium planes. According to you, these planes are inferior to those made from the 1950s to the present day. How can that be? You mentioned Juuma and Clifton, which I don’t consider them to be premium planes. You also brought up Woodriver, which is also not classified as a premium plane either. However, Lie Nielsen and Veritas are considered premium planes. Lie Nielsen planes are designed to withstand drops without shattering, have a flat frog with no humps, and a flat seating area for the frog. The sole is flat, with all sharp edges removed. The lateral adjusting lever and depth adjuster are spot-on. None of these features can be found on cheaply made modern-day Stanley planes. In fact, I recall watching your video where you attempted to refurbish a brand new Stanley plane to make it “premium” as it should be from the factory. At the end of the video, you concluded that it wasn’t possible. Still, I can’t help but wonder if what you say is true and if I’ve been misled. After all, I listen to everything you have to say. However, without questioning it, how can one truly understand the message you’re trying to convey?

I’m not sure Paul suggested inferior, but instead not much different (little advantage) to the ones he uses from the 1960’s.

I have never tried to make a premium plane from a “modern-day Stanley plane” that would be silly and impossible for many good reasons. I simply looked at what it would take to fettle one to make it good and usable so a bit of an over-exaggeration there. In the end, with all of its flaws, I concluded that it would always be inferior. I own the planes made by the better engineering and found no difference between the ones you mention. They all had equal levels of fine tolerances and good engineering. These would all be considered premium planes and especially so when compared to the general low quality of those more commonly known makers. I don’t expect everyone to follow PS blindly but to reconsider what I pointed to in the blogpost and try things for themselves to see if what was said was so, nothing more.

Thank you Paul I will take into consideration what you say and give it a go.

https://i0.wp.com/blog.lostartpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/201bfe5061.jpg?resize=768%2C560&ssl=1

I have found a picture with the bench height being at what you suggested!

no i will follow you blindly. all hail PS king of kings. haha. you are an enigma. on one hand you come across as a cranky old fart and on the other you are the kindest most generous wise and funny people i never met. and a grandmaster craftsman. your stuff will be found by the aliens after the anthropocene ends in a century or two. your sons must be lucky buggers, you old rascal!

P.S. please make more Worlds Best PS wooden planes: now with Com-Fort Handles…and show using them to make projects. wooden plane renaissance! hopefully this post finds you in good spirits.

Paul,

I have found that the wooden planes, I now own, have aided my understanding of plane use, and the experience has improved my planing, when using my metal bodied Stanley and Record planes.

I do like the ease with which they move over the boards.

I, too, have a admiration for the full-time users of Norris infill panel planes, as my one is so much heavier that my Stanley No.5.

Thank you for passing on your knowledge and thoughts to us new hand tool users; we all need mentors like you and George.

Paul a great article as usual. As a retired engineer may I add a small contribution. The cutting tool as we engineers call them, is only as good as the material it’s made from, properly hardened & tempered, sharpened and honed for the job in hand.

It will work fine in any device even a hand made plane. It’s efficiency is only as good until your eye or feeling tells you it’s time to resharpening.

A good article indeed, Frank; agreed.

On the topic of the steel to use for cutting irons, I’ve just started making my own woodworking tools mainly for my own amusement and as a retired engineer like you I’m well aware of the benefits of hardening and tempering but for what it’s worth the plough plane iron and two small firmer chisels I’ve made so far were hand-made from offcuts of square keybar stock left over from a contract years ago. I have done no heat treatment at all.

I don’t know what the steel spec is but I do know it’s not the easiest of stuff to cut and file and it takes a very good edge. And it’s inexpensive, or in my case free. Also the wooden parts came from scrap offcuts that were otherwise headed for the kindling bin so I now have three handmade tools that work perfectly well at the cost of £0.

And I couldn’t put a price on the fun I had making them!

Twenty years ago, I bought my first wooden jack plane. I restored it and practiced with it regularly. I now own several jack, fore, scrub, and smoothing planes dating back to the late 1700s. I also own three transitional planes that I restored and enjoy using. I rarely reach for my Stanleys as I have grown to respect and love the “old way” of wood on wood. Believe me, once you learn the ins and outs of owning wooden planes, you will hardly use a metal one again.

As always, interesting and thought-provoking. I’ve never used a wooden plane; I’m still learning how to fettle my metal ones properly. But I believe you. It would seem, then, that the chief advantage of a well constructed metal plane is the lack of wear.

Thanks for sharing your insights.

Surprisingly, wooden planes do not wear anywhere as much as you might think.

Wood on wood is always good!

That should be on a T shirt.

… and a coffee mug!

“Some woodworkers express things from their own background not as makers as such but as online presenters. By ‘as makers’ I don’t mean they don’t make but that they make on a more limited basis and purely to gain followers and subscribers.”

…..and many of them just copy your work and try to represent it as their own – the more honest ones will acknowledge you as the source but many others don’t.

I really enjoy your start-to-finish videos, including the occasional “woops!” when a rare mistake is made and your presentational style is perfect. Quiet confidence, clear instructions, no rush, no shouting, no flashy visual effects or loud music.

Personally I think you should be on the next honours list for your devotion to the craft of woodworking and for your teaching legacy which will keep these skills alive for future generations.

As for planes, I’m very much a novice but having gained some confidence using an inherited Stanley #4 I tried to purchase a longer plane but was finding that the price of #5s and #6s on Ebay was too much for me so I bought a 16″ wooden plane for less than £10 and after sharpening the cutting iron and fixing the cap iron to prevent shavings jamming between the two it takes very good shavings, as good as the Stanley. In particular it will, if required, take much thicker shavings than the Stanley when required for cleaning up rough sawn boards. I’m still finding the art of hammer tapping to adjust shaving thickness a bit finnicky but I hope that this will improve with practice. The Stanley is certainly easier and quicker to adjust and readjust on the fly.

As a beginner though I’m happy to keep working with both technologies and improve my skills with both.

Thank you Paul for helping me to enjoy my retirement by learning woodworking from you and please keep the content coming for as long as you are able to.

Regarding brittle steels and edge fracture, I did an experiment with some A2 chisels and O1 Narex chisels testing for edge fraction when chopping cross grain. I found the O1 was fine at 30 degrees, but the A2 had to be more like 35. The larger sharpening angle for the A2 means more force is needed to drive it, but what is more important is that it also means that an A2 will walk back into the knife line more than the O1. Those were fancy, premium A2 chisels but I never use them. In fact, I should sell them.

Very interesting, and chimes with my own experience. I have a woodriver (no 5), which I got nearly a decade ago. I think it’s been about two years, perhaps more, since I last picked it up. I just don’t enjoy using it since I got my old No. 4 and restored it. To the extent that it sort of leaves me without a Jack plane at all (not really an issue for the most part), because I use it so sparingly. I have a wooden scrub (European/German type) which I like, but I’m thinking that perhaps I should pick up a wooden Jack plane to supplement and sell the Woodriver. Is there anything in particular that I need to look out for when ebaying for a wooden plane? Obviously, size of mouth, blade and cap iron (as in, making sure there is one) are important, visible cracks or splits. Anything else? Also, is there anything in a plane adjustment hammer worth looking out for (particular weight etc)? I mainly use a cheap, plastic-handled thing I got from B&Q, which seems okay on the scrub plane.

@Paul Sellers,

You are quite right about the needing to learn to use wood planes. I took about 4 months and just focused on getting my set of woods (jointer, fore, jack, and coffin) to take good shavings. It was quite a learning curve to get all four working, and each behaves a little different. Still takes me way to long to get the initial iron rest after a sharping, and don’t quite have the nack yet to get the adjust right the first time, but once they are set the woods perform as well and in some cases better than my metal planes. The coffin especially, as it will smooth the wood even against the grain if I am careful.

I took Paul’s advice when learning and bought an old stanley and it was great advice. Particularly as it wasn’t expensive and following his videos it was easy to get it in working order.

I do love the wooden planes I’ve subsequently bought. They were trickier to get working, there’s often a variety of problems from them not being stored well that are harder to repair than removing rust from an old stanley. But the end result is a lovely feeling, they seem to make a much nicer sound I find, I feel a lot less friction and they’re so much lighter.

Hi Paul,

One of your comments you made “What about laying planes on their sides” about being tosh. This is something stressed in shop class in high school to us. I have noticed that you do not follow this practice in your videos and when you commented on it being tosh I figured that I would ask you why?

Thinking back I’m to high school I’m wondering if the Instructor stressed this to us because of abuse that many students did due to lack of respect for tools that were not theirs. I also recall that very little time was spent on proper sharpening (just one 10 minute lesson) and the importance of keeping a sharp edge on any tool.

Thanks, I truly enjoy your videos and blog.

the first plane i ever used was a wooden one my step father owned. as a boy of around 11 i had no idea whether it was good or bad. i just took immeasurable pleasure watching the shavings coming out as i pushed it back and forth. as someone who is retired, hence older than most, i do remember the old india stones for sharpening. a mix of oil and kerosine to lubricate. yet i could still shave hairs after using one. like you i have a love affair with the new diamond stones.

Thanks Paul, interesting article. Influenced by yourself, I have 2 larger wooden planes, 17″ and 22″ (I also bought a longer one, 28″ I think, for a friend and colleague who made a lot of this family’s furniture mainly using power tools and who felt longer was better for his needs).

I mainly use vintage and cheap new metal planes, sizes 3-5.5. I am fortunate to have an old USA Stanley #4 with sweetheart iron, and an English Marples #4 and a Record #3 plane. But I have some ok new Faithful planes and a Draper too. But I like wooden planes:

I picked up 2 small wooden smoothing planes that were cheap and unwanted at car-boot sales ( still haven’t used them though 🙁 ).

I also have a wooden plane with a curved bottom, which I repaired and use as a scrub plane but I think it was made for boat building, hollowing the sides of clinker-built boats perhaps?

I also picked up a couple of unwanted wooden rebate planes (still unused). And a wooden plough plane and separately the irons – which I have used :).

Also influenced by Paul, my bench is a little over 38″ :).

I should also mention one of my favorite planes, an English metal Stanley 5.5. Bought some years ago from a popular auction website for a very reasonable price, great working condition. I used it quite a lot at first but seem to be using #4 & #3 more recently – smaller projects/timber (and injuries).

I now also have a boxed second-hand Faithful #5. From the same website . From the little I’ve used it so far, it seems like a nice, smooth plane and a useful size (as the wood I use/reuse is often narrow). Better than I expected.

But I agree with Paul, the old vintage planes are often better (and can be very good value) and actually have better interchangeability of parts. That said, my spare new Draper iron fits my vintage Stanley #4. 🙂

Paul, After reading the story of the felling of the Sycamore Gap tree along Hadrian’s Wall, I was saddened like I’m sure were many other people, of the senseless loss of such an icon and beautiful tree. There have been many suggestions as to what should replace it, but having just read you article on planes and seen again that magnificent cabinet you built for the White House, I wondered if you had given any thought to making a proposal to use (some) of the wood from the tree to make another iconic piece of furniture so that it can be remembered long into the future. I have been following you blog etc. over the past few years and cannot think of anyone more suited to such a task. With your obvious understanding and love of al things wood, I can’t think of a better craftsman to perform that task.

I recently purchased a well serviced and restored Mathieson wooden Jointer plane and I love it. I love the weight of it and yet find it less fatiguing to use than even a Stanley no.6 plane. Unfortunately after a bad storm, water came into my garage and the plane was directly underneath. It soaked the sole of the plane so now it needs remedial work. It was next to my no.6 which has left a black silhouette against the side of the Mathieson. I’m gutted!

Paul,

As always, I enjoyed reading your newest post.

I just finished making a wooden Japanese cutting gauge to aid me in cutting the frame and internal pieces of my Kumiko projects. I believe there is no other way to understand the use of wooden hand tools than to craft one oneself and use it in one’s build process.

As you stated, it takes years to master the use and care of wooden hand tools. This is why Stanley and other metal tool manufacturers around the turn of the 20th Century excelled by taking these one-off wooden hand tools and making them into multi-functional and much easier tools to use.

C’est si bon,

I purchasse and refurbish old hand tools for use making the furniture and techniques you have taught. I was recently looking a video by wood by wright another fan of yours. He tested a number of old and new plane blades for all manner of factors; planeability, sharpness, edge retention, resharpening. That video convinced me there is a definite improvement in plane irons in recent years. I have a bunch of very old stanley blades sharpened using your teaching and they work incredibly well. I find I am in a unique position. I am not clouded by any opinions or past. My woodworking journey has been surrounded by a miriad of brilliant woodworkers. Paul Sellers Samurai carpenter, The wood whisperer and dozens more all with their historical experience. I have found myself using a miriad of different methods and I am happy to say hand tools have a permanent place and a use in my shop as does a table saw, jointer planer as they offer certain things. I love woodwoking and all the content creators such as yourself have kept that spark alive.

That is a great write up and there is a lot to consider and apply to my own journey. I built a pair of hock tools wood planes from kits and then went metal because, well I thought I was supposed to. But the wood fits my hands so well I keep going back to it. Your words are an inspiration, thank you !

Question 1/2: Why didn’t people glue a layer of new wood to a worn out wooden plane sole? If you look at premium german wooden planes, you sometimes see ones with a different hardwood as a sole. However, the glueing surface is zigzagged there. Would a simple lamination fall off after a while?

They do!

Question 2/2: Does anyone have advice for me about setting (or restoring?) a wooden plane? It is my only longer plane and I like it – once I manage to set it. However, setting it is so difficult. The iron does not move at all when tapped gently. When I slightly increase the heaviness of the hammer taps, suddenly the iron moves far too much. Taking out the iron needs very heavy whacking with the hammer, but taping the wedge less heavily lets the iron slip out of position.

– Do I just need more practise? Any hints what I should focus on?

– Or could something with the throat/iron/wedge of the plane be wrong? What common problems should be examined first?

You don’t say how long you have tried anything here, Chris. A few minutes doesn’t cut it. Mastering anything takes time. It could be that the plane is the issue but no one can really offer realistic advise without knowing you and seeing your particular plane though they likely will offer and this then is more than likely just an opinion.

Well yes. I’d say quite many hours over a few years, but as you point out, you don’t use long planes so often. And of course I’d take hints and pieces of advice as what they are: as ideas to try and to think about. So I’m still interested in any idea or personal experience someone might express.

I think that you just get it when you get it Chris, a bit like freehand sharpening! I find that I still really have to concentrate when setting the wooden plane and pay attention to the weight of the hit and the noise it makes. Whilst I might not necessarily get an accurate tap each time yet, I can always tell when I’ve hit it too hard or soft (without checking blade protrusion I mean), there’s just something in the feeling of the strike, from vibration to sound that is quite instinctive. Then, if you know what isn’t right, you instinctively know what is. It’s a bit like “feeling for square” when you’re jointing a piece of wood. If your fingers run along the face your trying to get perpendicular too, you generally just know when you’ve got it square. It obviously comes with experience, but it also comes naturally by just relaxing and letting your body do the right thing.

I found that I was yoyoing between not enough set and too much set and eventually realised that I was striking too hard, so I now use a very light tap with a small cross-peen hammer on the iron and wedge and a light wooden mallet on the plane body and I’m getting better results. I also find that you need to check/adjust the setting if you hit any hard knots because that sometimes pushes the iron back into the body.

Look for any dings in the blade that could “dig in”. Other than that, set the plane then tighten the wedge, and then set the plane again if needed. Fiddle around with this a bit. At some point, you’ll “get” it I think. Use a small metal hammer to set the plane, not a soft faced one.

Hard to say what your problem is, but these things has helped me. My wooden jointer is a dream to use! A bit of a learning curve to it, but well worth the time. I intend to make my own wooden smoother at some point. Wood on wood is such a different way to work! Way better than metal, even though that’s what I normally use.

Thank you! These are several hints I’ll have to pay attention to.

After a while of experimenting I have to thank you all again: There were several precious hints in your posts. The most important one might have been Iain Savage’s /small/ metal hammer. I switched from 300 to 200 grams, and wow, what a difference. I suddenly feel in control. The small hammer lets me give sharper but somehow still light taps to the wedge and the iron. I don’t know if this combination of sharp and light is total rubbish in terms of physics, but that’s how it feels.

For loosening, I use the “chisel hammer”‘s hard (white) side, which has the necessary punch.

The problem generally with Stanley style planes is the fore and aft depth controls. Any slackness involves a lot of twiddling to and fro . I improved that slightly by gluing a thin tab of steel in the slot to take up the free play .The tab is simply bent twice and glued in place. One old Stanley plane had a rivet holding the lateral lever that prevented the blade from sitting flat against the frog . The lever mechanism is inferior to a screw action .No question about that . The screw can be slackened or tightened without all the bits trying to fall apart. While planing some very hard wood with wooden planes I adapted the blades by gluing strips of emery cloth onto the blade backs to stop the plane falling apart against old hard knots .

Japanese Tools are well explained in a massive site by Covington and Son Tools. There is one picture about their wooden planes with ten or twelve planes in a drawer and every single one is placed on it`s side .Ouch . That touches a nerve .

The simple Japanese tubular handles which survive steel hammer blows have a metal ring which has to be adjusted by filing a 45 degree bevel on the internal front edge. This very slowly gets driven down [ but the handle will gradually get shorter ] as the angled edge of the steel ring compresses the wood to prevent splitting . The back of chisel blades is scooped out to make sharpening or flattening easier but that would be possible with English chisels like Wards. Some Ward chisels started life in a cookie cutter shape as though they had been chopped out in pastry . I still love them to bits though . The outer edges curved downwards . Wards are among the finest chisels you can get but flattening any chisel takes some real work .

For some reason your educated articles are starting to sound quite angry. Just know that we all appreciate the quality knowledge you help us with .

Anger is not in my vocabulary and neither do i get angry. That’s just for the record. Forthrightness is in my vocabulary and I would rather have this than anything on the ‘just-for-pleasantries side just to fit in.It’s not true that slackness leads to “a lot of twiddling to and fro.” That’s just an exaggeration and nothing more. A quick flick with thumb or finger and any take up is done with in a split second. Someone can pick up an occasional bad plane but out of a hundred and more I have had my hands on I may possibly have had one that I fixed in a few minutes. “The lever mechanism is inferior to screw action. No question about that.” Again, I do think that you are quite wrong in this! My levers on my few dozen planes all work exceptionally well to infinitely align the cutting irons perfectly every time and so that’s the reason all of those premium makers went along with them rather than the screw simply because it was so vastly superior. I don’t know what you are doing wrong but your saying, “The screw can be slackened or tightened without all the bits trying to fall apart.” suggests the bits fall apart when of course they never do. It makes no sense at all simply because nothing can ‘fall apart.” You see, nothing falls apart unless you are doing something exponentially wrong. What you have expressed as your ‘opinions’ shows probably not to take advise or too much notice from you. Actually, I am sorry to say that nothing you have said here is of much value or help and I am really calm when I say this. I have started taking some things down from time to time but never in anger or even mild frustration but because it can more of a distraction. I rarely do it though.

Speaking of “modern plane”

Google “RALI plane”.

Swiss made.

It is a kind of infill plane with a choice between heavy and light sole with stamped metal sides, plastic tote, button and depth setting.

It uses trowaway blades. Choice between chrome steel or tungsten carbide.

Some have an adjustable mouth.

5 year waranty. They aren’t cheap! (and one has to buy replacement blades).

I don’t intend to buy one of those.

Not sure if this is in keeping with the vision so maybe it could be retrofitted with a permanent resharpenable blade rather than buying into the throwaway blades?

Paul, you were experimenting with replacement blades for Stanley #4 and #5 about a year ago. One might have been from Spear & Jackson. Do you have enough experience with them to comment on them? I’d like to find a good source of replacement blades that are thin like the originals.

I have been using the S&J in my Stanley #5 for a year now with no issues. Secondhand should be an alternative too. I bought a new old stock for £9 recently.

When I see new old stock Stanley blades, they appear to be relatively recent vintage, e.g., was in yellow cardboard shrink wrapped packaging. I’ve wondered whether these are suitable or if like, say, Nicholson files, one might rather keep searching.

I think they target is people used to change the blades of their jointer/planer & thicknesser.

On their site, they present sharpening as being something to outsource to specialists (time consuming, difficult, costly, needing equipment, …)

And then trying to have captive customers might probably be part of their business model.

They seem to be proud of 825 m of shavings with one blade side (1650 m/ blade) in spruce.

But how long would that be for you, 1/2 an hour?

As I said, not for me.

And certainly not for you.

Obviously, as you sharpen 4 times per hour, sending blades to a specialist wouldn’t make sense.

Paul: Have you made any videos where you have built your own wood planes?

Yes. Got to woodworkingmasterclasses.com and dig through the videos there. Any tools made or techniques in using them are always free https://woodworkingmasterclasses.com/videos/making-wooden-planes-info/

In school they tried to teach me woodworking, I enjoyed it but I was all thumbs. Remembering how much I enjoyed it I decided to try to teach myself, with your help, more than 50 years later and I am still all thumbs but gradually improving. I found that trying to true-up wood I would try one plane after another as one seemed to work for a time then fail. I recognise, as a result of your article, that this strategy is almost a guarantee of failure. I have decided, therefore, to work with only one plane for as long as it takes to master its use and sharpen the iron much more frequently. The one I have chosen is a wooden jack plane and I intend to enjoy the challenge. Thank you for your inspiration.

When people say they intend to sharpen more often and then sharpen twice in four hours I’m thinking to myself ‘They really don’t quite get it yet”. Working on a piece today, spalted beech and very difficult grain too, I sharpened my #5 1/2 four times per hour to save work and I planed for a full four hours. Remember I never grind on a grinding wheel either. That saves me a lot of time too. My sharpening time per plane is under a minute and back in the saddle.

“I sharpened my #5 1/2 four times per hour to save work and I planed for a full four hours. ” Wow! Impressive and a very useful insight, thank you Paul. 🙂

I was taught almost all of my woodworking skills at school in the 1950’s. We had wooden planes with cambered irons as part of our kit of tools, which with only one or two exceptions matched Paul’s ten basic tools. It served for all the planing we did except for a metal smoothing plane (a no4 I think) which was used very seldom and only as I remember for final smoothing of a few things. There was one for the whole class! I recall finding it very awkward, being used to the wooden plane. Like Salko, I have back and shoulder problems, not from woodworking. A bench height of 38 inches works for me, even though I am two inches shorter than Paul, and I am even thinking of raising it an inch or two to give me a more upright stance still. Follow Paul’s advice! The other thing I have found is that the slightly greater distance between the tote and knob on a No5 plane than on a No4 seems more comfortable to use now as I can hold my shoulders a bit more open. I find myself reaching for it more now in preference to the No4. I know this is very subjective, but it may be useful to others.

Saw no mention of Krenov style wooden planes or Japanese wooden planes. My experience with both are that if properly tuned as with any good plane they hold their own with any others. I’ve made several Krenov planes and once you get the hang of setting the plane depth can work wonderfully and can be made for easily under $100. Many fine pieces of furniture have been made from either of these types of wooden planes.

Not so easy for a new woodworker without tools yet or a bench to make from. In fact, its about impossible. I just give people what they need.