Making Wood Work

Throughout history, making tools of all types has always been a part of many a woodworker’s life. The ones that were skilled enough to produce levels of excellence surpassing other woodworkers became tool makers. they established patterns of work and design that exemplified levels of refinement other woodworkers wanted. Instead of being just carpenters they became tool makers of excellence. When wood married metal in the making of tools more specialised makers adopted specific areas of making that raised the bar in their craft. By competitive making, those who made the best stood above the rest. Wooden planes in Britain came from massive beech trees where in Britain the trees thrived to stems of massive girth: a three-foot diameter, twenty-foot long trunk is commonly found. Two trades harmonised side by side with blacksmiths hammering raw steel into cutting irons and plane makers making a wide range of plane bodies numbering 300-400 types in a massive range of profiles, sizes,etc. Metal foundries grew in number over a couple of centuries and specialisation took on the work to mass make cutting irons and cap irons for the makers of planes. For saws we had amazingingly beautiful saw handles the like of which modern makers merely copy using powered equipment and leaving the telltale signs of power routers and CNC machines.

I make a plane I need when I can’t find one to suit my work. Most often I do own a plane that matches the work I want to create and this is more the convenience rather than my preference. But there is something about making a plane to make a coving mould three inches wide for a three-foot length you just cannot but and would be far to expensive to tool up for. In an hour I can make such a plane from a two-by-four scrap no problem. Owning most manufactured planes satisfies the majority of my work until I need one that’s not common and that then sends me to the bench to make one. When Joseph and I made his first cello we needed a round-both-ways plane to shape the insides of the front and back plates, We took some wood and made one and an hour later we were shaping the plates. Another tool we didn’t have was a purfling tool to inset strips of purfling the strengthen the rims of the instruments. We made two. One was a more traditional, commonly used version but then I invented a second one that just worked so much better but remains my own unique design. From plough planes to smoother and even some saws, I took the raw that once existed as a tree or a branch or a scrap from the bin and together with some steel from an old file or somewhere other than a tool I made what I needed.

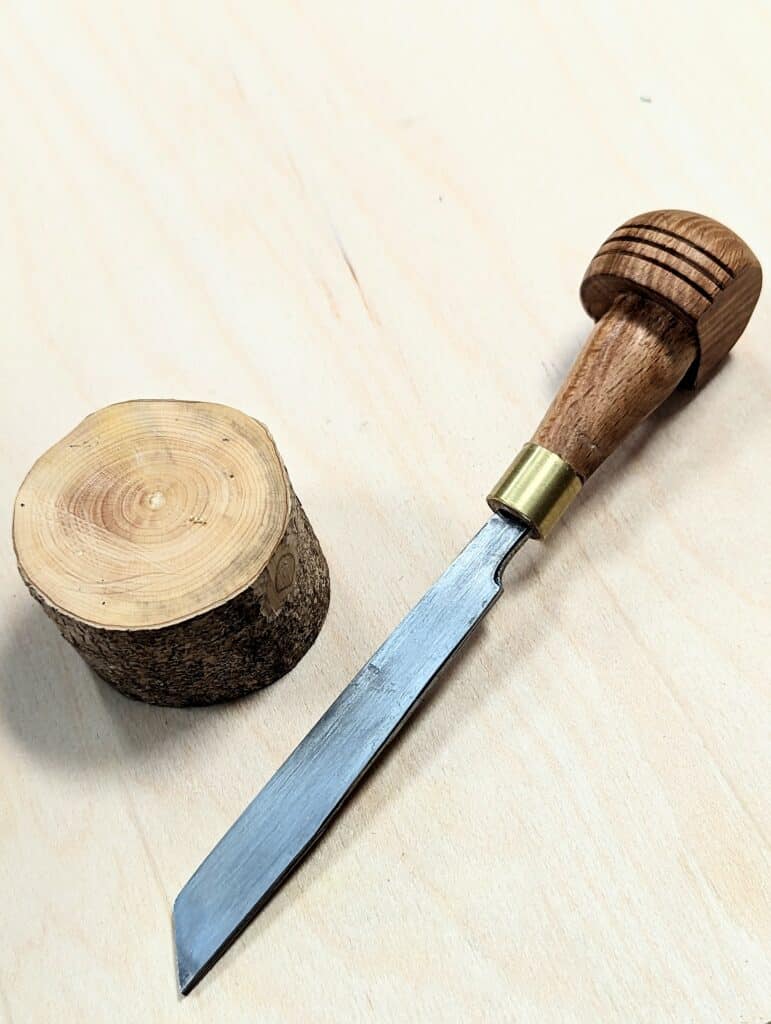

For wood block engraving and lino cutting, you need tools that have no use elsewhere. Unlike a bench plane that’s commonly used in joinery and furniture making alongside other woodworking crafts, gravers are pretty dedicated tools with no second craft in the background. There s a contrast between block engraving and lino cuts. Whereas gravers for end-grain engraving relies on a single, bevel-up cut that cuts upwards from the underside of the wood fibres in a thrusting push cut, lino cutting generally comes from bevel-down cuts using a variety of profiles in like manner to wood carving tools in relief form. Drawing a comparison, wood block engraving delivers more refined image in much tighter restraints. I know both realms can be highly skilled, and an artist one usually works in the other for different output, but the wood block delivery is much more demanding in many ways.

In buying graving tools and then using them I realised that some of the tools benefitted from a slight bend along the long axis of the tool for a couple of reasons not the least of which was to ‘bend‘ the strokes or increase flexibility. I also wanted some highly refined supremely fine lines for different work and outcomes. Heating the blade allowed me to tap-bend the lengths and I found that the tools were more versatile and more comfortable to use.

There is a graver called a multitool which may or may not be a misnomer in that it may function to create different stroke but that depends on the artist/user and less so the ability of the tool to be changed for different tasks. Think plane with different cutting iron widths and/or profiles. These multitools simply enable precision parallel lines to run along the surface of the wood block. The one I bought cost £57 including shipping. It was way to fine for what I wanted. Looking around my shop I saw a discarded bandsaw blade. I snapped off three four-inch long pieces, ground off the hardened teeth, squeezed them together and thought to myself, “This will work”.

I didn’t have the soldering materials I needed to unite them permanently together to hand so I reached for the super glue, scored the surfaces of meeting steel with coarse sandpaper and glued them up. I ground and filed the shape I wanted and sharpened the bevel and applied it to the wood. It worked quite beautifully. The cutting edges of the triple layer are on the back edges of bandsaw blade sections which is already uniformly rounded and ultra smooth. I can change that profile from round to V with a slender riffler needle file. or make a second version with sharper profiles as I like. There is nothing more to do to this. Pushing the tool along the surface of my boxwood with the ploughing action was really a treat. My next task was to make the idea and prototype permanent with something like silver solder.

My second tool I will update you on later.

I’m never likely to do the woodworking that you do, but I do enjoy your posts.

Reading them transports me for a few minutes… then it’s back to earth.

I’m a fan.

I’m a fan, too. I belong to a woodworking group on Facebook and Paul’s name is constantly referred to in the highest of esteem.

Oh, it is not only on Facebook, as I’m sure you know. I frequent quite a few forums where the mere mention of Paul Sellers often finalises a discussion. Even on the woodworking sections of apps like Reddit he is highly regarded and often mentioned.

Your “round in both directions” plane is exceptionally handy for rough sawn lumber. With a couple strokes, one can get through the fuzz to see the color and grain of the wood before roughing out parts. It’s better than a block plane, which needs to work enough area to be level enough to get down a bit. Which reminds me…I’m in idjit. I’ve been unhappy with my block plane for various reasons and now realize I should just make one as I like it. The one I have is uncomfortable in the hand and, more importantly, the setting gets bumped during use. A little wedged block plane wouldn’t do that and I don’t think the low angle bed is needed. I’m looking forward to seeing what you do with the engraving as I know absolutely nothing about it. Purfling isn’t just decorative???

No. Its for strengthening what are otherwise weak areas because of the different changes of grain direction with some very short grain around the main body of belly and back around the edges. Quite fragile on the ‘C’ corners, etc on all of the bowed range of instruments.

does anyone else have the supreme joy at seeing Paul liberate a 4×2 2×4 block of unassuming pin and some scrap steel and elevate it into material’s highest form: a beautiful masterwork tool?

i dont like the metal stanley planes or any other mass produced plane compared to a simple block of wood that Paul made. no comparison! even if that bailey pattern is great, maybe even superior in some ways. i crave the bespoke planes and other tools. there is something primal not primitive about the hand tool of the ancients that stirs the imagination.

It never dawned on me that inlay or purfling was used to strengthen the short grain on string instruments. I may never make an instrument like that but the principle could be used in other places. Thanks for sharing that knowledge.

Ah! Well, cockbead does the same as this was often used with facings of veneers when veneears were hand made to say 1/16`’ thick. same for binding on guitars. We used binding on the outer corners of drawers, edges to tabletops and such. What looked like decorative often served in two dimensions, decorative came after functionality,

May I add a detail Paul told us in class, hoping that I recall correctly? Often, a drawer face is veneered, but the casework is solid wood. The proper thing to do in this case is to attach the cockbead around the edge of the drawer itself, _not_ around the opening in the carcase. Done this way, cockbead absolutely protects the veneer from being scraped off the drawer during use. This detail seems to have been forgotten by many modern makers who see the cockbead as a decoration or don’t understand its function, so they attach it to the case instead of the drawer. I suppose there might be some benefit because of the rounded-over edge reducing the tendency to snag the veneer compared to a sharp corner, but not as much as attaching the cockbead to the drawer itself. I have certainly seen quite a few instances of damaged drawer veneer when the cockbead is on the case instead of the drawer. I’m not sure what was done traditionally if veneer was on both the casework and the drawer. Let in a thicker stringer around the opening in the case and cockbead on the drawer?

Thanks for the insights, Paul. I’m wondering if you have ever built a version of a shoulder plane? They are crazy expensive to buy brand new ($350 for the large one from Lie-Nielsen). Or what would your alternative suggestion be to refine shoulders on a tenon?

Thanks!

Andy

because I advocate knifewalls for shoulders to be cut to there is almost no need for a shoulder plane hence I have never used on on any of the projects throughout woodworkingmasterclasses.com. I would say that this is more a luxury plane for most woodworkers. The can be nice to own if you happen to have one and even essential for a very small number of woodworkers in their more specialist work. Essential and worth the money? I personally do not think so.

The knifewall technique has done more for my woodwork learning than any other single thing. A real revelation.

I for one would relish the idea of Paul introducing how to make various other type planes. For example hollows and rounds for producing your own personal mouldings. Hopefully that could be a future consideration.

Thanks Paul for sharing your invaluable knowledge!

What a lovely thing to read. I started making my own file handles years ago just because I didn’t like plastic handles, although they work okay. I just disliked them and found I could make one in about half an hour for £0 from scrap.

Then one day I wanted a smaller chisel than the smallest I had (1/4″) so I had a go at making one (3/16″) from scrap keybar steel and wood with a ferrule from scrap plumbing copper.

I use it often and made another (8mm) just for fun.

I made a plough plane from an offcut from a fence stob. It works just fine.

I’d show you a picture if I could.

There can be few things as satisfying as making a tool, or anything else, that should be perfectly serviceable in two or three hundred years.

A delightful post Paul. Thank you.

Regards;

Rod.

hey man I’m scott in uk hull I watch alot of u grate I downloaded ur last book with pics in coulur and measurements I watch you in ur work shop n I think instantly wow and I don’t havecany tools yet at college doing settingbout rods and how to work from them I’m after bench joiner sites do my head in please

love to have one of ur hand planes raily love watching u use them n make them brilliant