Persevere

Thank you for your support in buying my router plane. The income from the plane sales supports many aspects of my work and then my ‘other‘ work beyond. I wish I had had it for my book back in 2015 and before but, hey! We are where we are. I remember arriving in the USA and shortly after my migrating there, travelling around the Woodcraft stores in different places to demonstrate the real value of mastering hand tools. The seats always filled and the aisles were packed to the hilt too. We’d usually start around 7 PM, plan on going till 9 PM but still be there after 10. I would bring my own bench on a trailer and my tools — the store benches were always 3-4″ too low. The audience was always amazed by my workbench height but after a good explanation, they suddenly confessed that they saw why they now had backache after backache. Though I never charged anything for demoing, even when it meant a hotel overnight, they often had a private whip-round and gave me a hundred bucks; such was the spirit of the woodworkers USA.

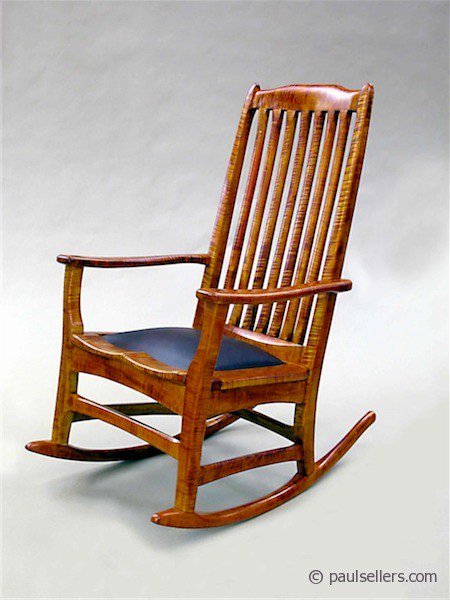

The main interests always surprised me. What I took for granted I would draw them into my hand tool world in just two minutes by cutting a two-minute double dovetail with a gent’s saw, a knife, square, chisel and a chisel hammer and then hand it around, smooth and gap-free. I could make all four corners in under ten minutes and have the box planed in two more minutes. I met many of you at these events and also with The Woodworking Show US tour that travelled the USA.

In my show-off days, I would demo dovetailing using four different-sized saws including a panel saw. I was proving the versatility and the functionality of western saws in the face of the onslaught wrought by Japanese makers and importers of the day. Quality western makers were almost gone by then and the magazines became ever-more interested in Japanese woodworking as an alternative option in light of the demise of western woodworking. These guys always showed planes whipping off a shaving 3″ wide and ten feet long or a myriad of highly complex joints as though this was day-to-day joinery used day to day by furniture makers instead of temple builders and repairers/restorers. I always wondered whether this happened in real life. many things are done to draw us in. Economy and consumerism are universally impacting and it’s a special cluster group of the more wealthy who can afford truly handmade work. I still try to see the real value in three-metre-long shavings in Japanese Cypress when only a handful of makers build anything like temples or use Japanese cypress wood.

My quest at the time was to counter the erroneous conceptions both in the use of traditional hand tools from western makers and how they really apply to our real woodworking world making woodwork work. Having said that, I think some really fine woodworking and concepts of design comes from Japan — both modern and traditional. I also think it is important to understand the spiritual implications of making by hand using hand methods too. Mostly it is in the concepts of design and the joinery used that interest me as a maker using hand tools. I love the idea that certain crafts still seem to hang on in there. Japanese basket weaving and miniatures always draw my eye.

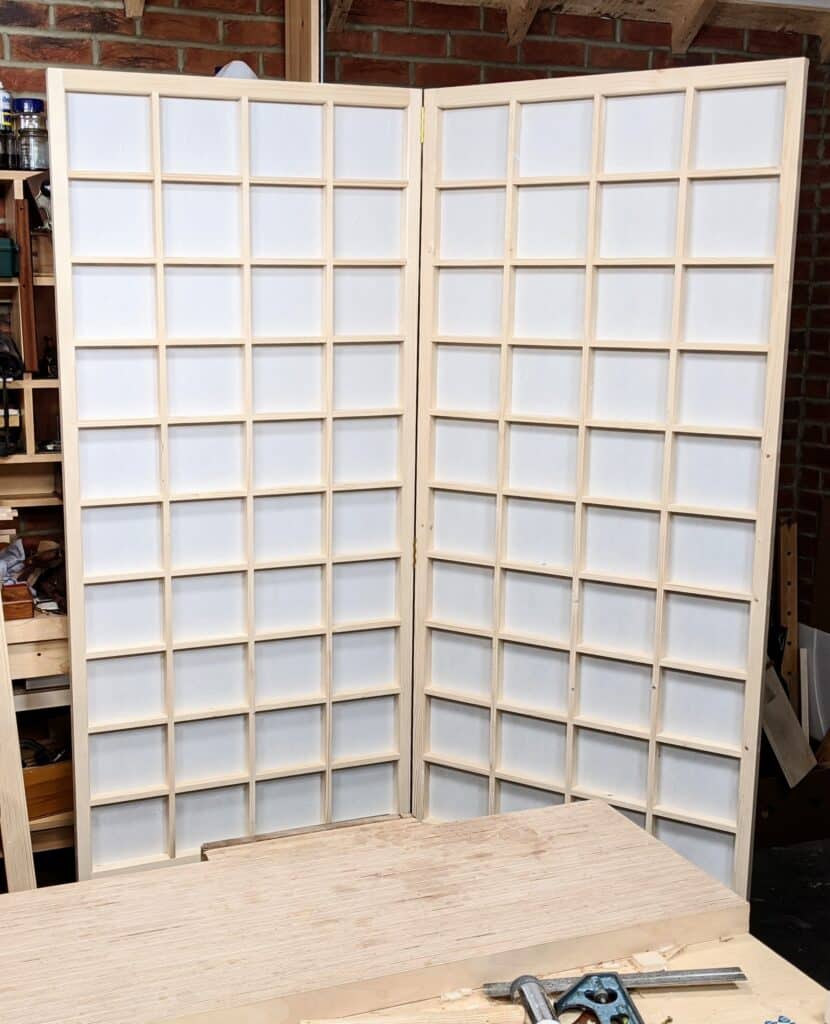

The lightweightness of room-dividing shoji screens fascinates me too. I use my shoji screen every day as a room divider and privacy screen. Make two or three and you have a private room to draw and paint in, filter, soften and distribute more even light for photography. I create a backdrop in seconds for displaying my pieces. Remember we made one for woodworkingmasterclasses a couple of years back?

We find the real at our own workbenches in the quiet places and spaces physically and mentally of the day negotiating the wood and the tools we use. We must make a decision at some point that takes us beyond the fascination of a shaving rising from the throat of the plane or the chisel’s edge or the mouth of the spokeshave to the direct quest of planing surfaces by the dozen true and square, parallel too before the joinery takes place at our fingertips. It’s to this end we must take ourselves, still equal in fascination, on to become not shaving makers but men and women who become masters of the craft of woodwork. We live and work when we can in a multidimensional world where craft is the art we immerse ourselves in. Establishing the cutting edges we rely on is the merest part of our day in the shop. The wood becomes the partner opposite to our hands where the constant reduction takes place. This then becomes our real woodworking.

Even now, at 73 and through a lifelong full-time woodworking passage, I still enjoy the union between one piece of well-cut wood that fits perfectly into an adjacent piece. When it’s loose I fill a tad disappointed, but I consider it in relation to the other surrounding parts and nine times out of ten it’s of little if any consequence. If the tenth one matters even slightly then I remake it. I am not a perfectionist. I don’t believe that obsessiveness is perfectionism. There is rarely any sense of harmony in such a condition or a person though I do accept that it can be a condition to the point of becoming a disability and very discontenting. Woodworking is about the discovery of balance. It comes through a period of transition where skill has yet to arrive but you are on the journey. I worry that our instancy of clicks and artificial images gives us unreal expectations. My becoming skilled in my craft and others came through the years year on year. What I didn’t know and couldn’t do came split by split, saw stroke by saw stroke and plane stroke by plane stroke. Each one of the faltering strokes that halted me, jolted me with an awkward wrench taught me patience and led to greater care, greater interpretation and a seeking ahead of the tools to understand better my wood and my tactics to tame it.

Everyone can master hand tool methods of woodworking and become well able to work it if they understand the essentiality of patience. Hand-tool woodworking is not for the faint-hearted but neither does it have to be instant either so just take your time, think about what’s happening at the cutting edge of your tools and be prepared to change direction with the tool on and in the wood. Anyone who perseveres will be rewarded by a deep satisfaction that they pitched themselves against the odds. I have seen too many successes to believe differently and it all begins with a sharp, sharp cutting-edge!

Sadly the woodworking shows don’t offer any hand tool classes anymore.

My son and I have stopped going. Lucky we still have the internet!

Agreed Tom. I’ve stopped going for the same reason. I met Paul at the Fredericksburg, VA show in 2012. Paul’s presentation was amazing and inspired me to persevere with hand tools.

As for the internet I rarely seek advice or instruction from anyone besides Paul Sellers. The other internet woodworkers I watch reference Paul on a regular basis. How many people can say that about themselves regardless of their vocation or profession?

David, that is so true.

I started woodworking with hand tools about 7 years ago; I had always wanted to, but thought I was just a “mere mortal” who didn’t stand a chance.

Then my father gave me a Stanley #5 and I went on Youtube looking for how to use it. I saw Paul Sellers demonstrating hand tool wood working, and he was the first person to demonstrate it in such a way that I understood.

About a year later I started a small (still) Youtube channel as a novice to demonstrate and document my progress.

He not only gave me a love of hand tool work, but a desire to encourage others to discover it, and to celebrate it.

I am always confused by your posts. I can’t determine if I love your skills or your life philosophy more than the other. Either way please continue. Even as I near my mid 80’s your ideas continue to make improvements to the utility of my shop.

as i turn 71 this year and see that you are a tad older then me still in the wood shop thats my goal thank you for the inspiration

Well, Ben, I hope that this inspires you still the more. I start work writing every morning at 7 am and eat my breakfast as I write for two hours. That can be cooking my own breakfast ready to eat at 7 am or arriving at the cafe at 7 where the cafe prepares my food. Around 9 am I start physical work and work for four steady hours at the workbench. I take an hour or so for lunch break but rarely eat lunch. by two I am back at the workbench and work until between 5 and 6 pm. After supper, I catch up on texts, messages, comments and so on. This might take an hour. I then read for an hour to round off the day. This is usually six days a week. Sundays I like to rest more but that does not mean no shop work, just not planned or scheduled. It’s been pretty much that way since my involvement using the internet–the last 15-20 years. Before that, I worked in the shop from 6 am until 11 pm most days.

Paul, if ever again you come to the USA (especially New England) I would be glad to throw a few bucks in the hat when they pass it around. J.R (Ronn) Winn – Vermont

Paul I have been following your internet teachings for several years and even though I do not work at doing woodworking as I wish I would I continue to prod on, your teachings have help me so much even though at time I feel as doing some of your projects are some what diffcult and am afraid to try them I continue to try making my own projects using your method of doing wood furniture. Sorry to say I do not make many things but because of your teachings I use handtools and feel great doing projects that way, so I wnat to thank you for what you show us on how to use the tools. I wish I had met you when I lived in Texas but I did not but I still wnat to thank you for all you have brough to the table for me and so many others. Hopefully your son will have his own internet teaching program so that we do not lose how to work with Hand tools. I am not saying this thinking your are stopping anytime soon just as a wish for those of us in the future so that they too can learn. Again Thank You very much for all the help you have provided me and so many others

Carlos Alvarado

St Paul, MN USA

I had used power tools for years and did hand tool woodworking in middle school. But I needed a better workbench, and saw Paul build one in the yard, and said I can do that. Then after watching Paul some more, I learned how to sharpen and my hand tools where better, but after some time I got them really sharp. After trying Japanese saws and never quite getting it, I learned to sharpen western saws, and after practice over time they cut straight and smooth. And it is amazing what a well tuned hand plane can do. And last and not least is the techniques to accomplish joinery by hand. I want to thank Paul for being a teacher and inspiration to me and others to aspire to greater things and they are not beyond our abilities if we stick with it and keep trying;

Thanks Paul. I especially liked your comments about the perils of perfectionism. One of the challenges of working in my garage mostly without others (i’ve had a few classes now), is trying to understand what is realistic in terms of what joinery should look like. Each piece I strive to be a bit better. After 7 years, I’m pretty happy with the way things look. Still room to get better. Do you think it would be possible to expand on the topic of what good joinery looks like and how much of a “gap” is too much (is a 64th a big gap say in dovetails?). If you could share photos that would also help. I’m not asking to poke fun at others, just trying to have realistic expectations. I’ve reached the point where I won’t give up but I can see others thinking maybe their work isn’t good enough could feel frustrated and stop woodworking. Just a thought. Thanks.

Yes, I can take a look at that. In general, I disallow gappiness in visible dovetails but when dovetails are all tight and a shoulder line is compromised by end-grain compression caused by a softer wood or a heavier-than-should-be chisel strike, I might let that go and risk the judgement of others. The angles of my dovetails almost always are as near to this illusion called perfect as I can get. Without an intentional pun, it’s a thin line between a gap and a good line to see. But you are right, some things you can let go of, an overrun with a saw stroke on a tenon shos on the top of a door or a dovetail. Look at most antique pieces and you will see them everywhere. Of course, back in the day of Queen Victoria, King George and such, men were under different pressures from bosses and customers. There were ten men at the gate to replace them for less money and longer days. I hear on occasion people say their work was better than those of older craftsmen and they are software engineers, not furniture makers. I remind them that a three-hour dovetail working in pristine conditions, fluorescent lighting and top-quality tools is not quite the same as working by candlelight in a dim and dark workshop cutting six sets of drawers with four corners to each in a ten- or twelve-hour day.

Carrying on from what Joe said, I think you are in a unique position to address this need (showing what things really look like) because of the photography skills you and your crew have developed. As a specific example, you could demonstrate the typical imperfections in a surface as it is developed. Show the undulations after scrubbing, first level refining, and final smoothing. This will require getting the camera to view raking light, just like you do with your eye. Try to show how much you leave for the scraper or how much imperfection you are content with when a surface is, say, an exterior surface that will planed again after joinery vs. an interior surface that really cannot be touched again. One metric here would be, any time you think to yourself “good enough at this stage,” stop and try to catch it on camera. I suspect a lot of people suffer from unrealistic expectations.

You had the benefit of having mentors who would teach you to see (in all senses, not just sight). When I show people things, I can tell they often are not yet ready or able to perceive. Repetition is needed in which they compare their judgements with mine. The same thing happened with my daughter learning the viola. Her teacher could show all sorts of mechanics for a bowing technique, but until my daughter could perceive and hear the nuances in sound, those mechanics could never by themselves produce mastery. She had to perceive the goal and then find her way to it. If one cannot perceive the subtleties, one cannot use them for expression.

Thanks Paul. I appreciate it. I used dovetails as an example to the wider topic of realistic expectations of fit and finish.

Yes. I understood that. Dovetails are really a good example of what’s fit, what fit is and with all of the visible parts to a finished common or through dovetail it’s a great example of where and what to look at.

I also first met Paul at a Woodworking Show here in Arlington, Texas. the Cowboys and Rangers’ Stadiums now nearby. I attended the foundational classes in Elm Mott where I met several of his proteges. I miss not having Paul nearby, however, his internet presence is benefitting many more of us, including other YouTubers. Thanks Paul.

Thank you Paul. This article strikes a chord. I’ve been working on hand tool joinery following your steers for the last 3 years now. It’s a slow learning process, for me at least, with many hard lessons – usually from trying to cut some slight corner. Where I am now is spending perhaps three quarters of my time in wood preparation rather than doing actual saw work on joints. I’m still learning to get the tools really sharp – each time I find what I thought was sharp was actually only part way there; and I’m still well short of expert! Then Getting the stock square, all the way from end to end – I’ve made square stock, but with slightly ragged ends. Of course it’s the ends that often matter most as they are where the joints are! Then laminating boards. Here in an Oxfordshire garage with no heating I’ve painstakingly made up true boards in oak, only to find a couple of weeks later they have become bowed and cupped, to such an extent that I’ve had to rip apart and laminate again. It’s a hard learning process. But I’m learning, usually the hard way. But the small steps, like finally getting my cabinet scraper sharp and working, feel like triumphs. Making these steps, around a day job and a young family, don’t come round as often as I’d like. So patience is indeed the key word for me. Alan

Much as I’d love to testify what the discovery of Paul Sellers’ teaching has meant to me, that would be far from unusual or unique. I’d rather point to how unique the historical coordinates he occupies are. While the apprenticeship system and journeyman mastery it grew out of are gone, Paul’s virtuosic use of computer network communications has documented and preserved (at least major portions of) it. He combines the best of a passed era with the best of a new. I fully expect his teaching to stand the test of time long after we are gone. But it isn’t merely mechanical details and physical techniques. It is a lifestyle package of physical routines,

imagination, esthetic judgements, and creative expression. In short: the art of living and meaning of life!

Paul, at my first woodworking class with you in Texas I asked one of the assistants how we were going to make the box lid round. He said ” with a plane” and I was shocked. No way I’d be able to do that. Now I don’t even have to think about how to do it. That was almost 25 years ago. Thanks Paul!

Hello Rod, Amazingly for this 73-year-old, I remember you. Hope you are well. Yes, it’s amazing how we take ownership isn’t it.

Mr. Paul,

my name is James and I am located in Selma, North Carolina. I love your videos and your teaching.

Thank you so much!

Such a beautiful story, Paul. Thank you as always for sharing. The spiritual and dimensional connectedness of working the wood is where it really happens….agreed! Being open to the wood guiding us as it opens up it’s story to us, while the Jack appreciates the parishes and their beauty while floating back toward the ground. Thank you for the inspiration and outside validation!