Allowing Time to Master Your Working

Growing woodworking skills to become an owned and well-earned craft takes time. For hand tool woodworking there is no substitute. With hand tool woodworking you cannot extract yourself from the whole high demand process by sending wood along fences, into power feeds or along alignment jigs like power router guides that cut dovetails in place of us. The sensory essentiality is magnified a thousand fold in the same way walking, sport like rock climbing, hiking the wildernesses cannot ever be matched by a video for the total reality of the immersive experience. Try to explain to the video watcher your slipping into the upper reaches of the Dry Frio river for a wild-water swim and all you will see is the eyes glaze over with the thought of, well, all that effort.

For those choosing the harder climbs, the steeper rides, the longer distances, the rewards are phenomenal. Yes, it’s demanding, but who is the one demanding it but us as individuals. These high-demand levels through self-discipline and self-development are no different than they would be for sports training, research, self-education and very much more. Those who rise to the top in just about any discipline you care to name got there by high levels of self demand and self discipline. They chose the path, stuck to it, lived it, came through the hard and often gruelling pinch points and all to gain the ultimate mastery all skilled work demands. We do what we do because we live for the uniqueness no other means gives us. It soon becomes clear that sharpening, accurate layout, dextrous hand skills and then, above all, exercising the whole body and mind, results in becoming a master. But this is a positive endeavour if we have the right attitude in our life choices in the work we carry out. Without even noticing, we find ourselves living for every difficulty. The fulfilment of hand making becomes our second-to-none moment when we must flex to absorb the rougher fibres with the surface cut of our plane’s cutting edge. The needs switch moment by moment and we find ourselves then shunning the filters of industry that otherwise separate us from engaging more fully with both the wood and tools to work it.

You and nature are conjoined, then there is no industrial processing to make what we make be that making a wooden ladle, a coffee table or the mirror frame. As I just said, establishing skill takes some practice, but experience has proven that everyone can cut a good dovetail and plane wood dead square with nothing more than #4 bench plane like a Stanley with its thin iron and ordinariness. With the right instruction and some dedicated time to learn everyone can match my skills and even better them. Spend four hours a week making for a few months and within a year you should be able to make everything I make using only your two hands and a two dozen hand tools max.

Often enough, I find myself explaining that most under say 40-year-olds sadly progressed through periods of neglected upbringing when it came to early mentoring in working manually. That’s the power and dynamic culture has on everything we do from sleeping to eating to working and being entertained. Because of that, owning parents that may never have seen much of or been involved in manual work, and then specifically the use of hand work in craft, the more hidden benefits such as skill may seem not to offer much of real value to their children. Today, we find so many would-be hand workers in craft came to it much later and as late-starters never had the benefit of owning such benefits early on in life. Add to that that so little is in fact crafted by humans these days, we see a dearth of places and spaces to practice almost any art except at the most novice levels. Thankfully though, the craft of woodworking in all of its many diverse areas is safe in the hands of amateurs and these are indeed the ones who carry the treasures with them in their home workshops. Those pursuing craft of hand work often came to it and now come to it through personally feeling the lack of multidimensional methods of working in their lives. What I have described through the years as amateur woodworking, what others call hobby woodworking, is nothing less than a driven force in the desire to make and to make mainly if not wholly by hand. There is something true and non-fanciful about it. Something non-fantastical in it. It’s simply applying the honesty of manual work to your life that fulfils the the creative in us. Personally, for the main part, I can’t imagine a life in non-making realms and when we feel the interest stirring then there is a dynamic that just makes things, even the impossible, happen.

I have learned though that rarely is it ever too late even though ideally the age of apprenticing should be between the ages of 12 on up to the late teens. It’s unlikely that anyone is looking for an apprenticeship in woodworking these days as the market for goods is so tight and competitive it can be hard even to think of making a living from any kind of craft work. But people are looking for good training and I don’t mean entertaining videos of someone skilled showing off. For most today, true and bona fide apprenticing (if we want to call it that) will never be an option. I think it is fair to say that most people will have had minimal if any exposure to the kind of manual or craft work I speak of. Our culture is such that it’s now the majority of under 30-year-olds who have no experience of work extending much beyond their keyboards. This too should not be dismissed as it is also skilled work but of an utterly different type and dimension. It’s not hard to work out why. Though neither would be considered manual skills nor manual labour, they both require dexterity that comes through rote repetition with regular maintenance exercise. I doubt anyone could survive too well without computer skills to direct the machines that make. Spectating sport seems to be much more highly considered than the arts and crafts fields once offered by most cultures. In my early teens I was forced to take part in sport and so chose long distance cross country because no one else did. It worked until I could finally quit school and start work. Unfortunately, I was a reasonable cricketer and footballer so was picked for teams in school but I would rather have been in woodworking and metal working venues rather than chasing a 9″ ball around a field for an hour. Oh, well!

Because starting our craft now comes quite later on in life what I’d learned by aged 16 doesn’t happen until higher education and worklife is well and truly established. But we amateurs shouldn’t in any way despair. We all were built to make. By that I mean our brains and bodies have all we need to take anything we care to name from the raw and make what once grew and convert it by craft into something functional and fine. We can do it at any age as long as we are reasonable healthy and have a mind to. It’s as simple as that.

Starting any craft late means waking up the dormant or latent untapped resources within every part of our being, often believing the opposite to what our mind might be saying in the privacy of our minds. Our sensory perception and receptors will gradually come alive within us as we explore the thing that excited us as a thought to get started. This genesis kick-start begins a process as we take those first evolutionary steps. Bar none, we were all undoubtedly born with ability to make. Your hands and bodies were designed to that end but that ability, when and if left dormant and denied for whatever reason, will initially feel to be more awkward than natural and so the outcome of first works might not match the ambition that triggered our move. Untapped during the more formative years of life is usually no more than a basic delay in development. Unfortunately you might well need a little more patience in achieving the results you hoped for starting out. Don’t believe it when you think you will never cut a straight line with a saw or plane two faces dead on 90º one to another. It takes training to achieve such things––training and self discipline. And don’t worry. I never met one of my 6,500 hands-on students that didn’t make great projects. The importance of getting the foundation right is critical. I’ve been working on this for three decades to date. My first class back in 1990 gave me the burden. I never stopped my personal making though. Alongside my more industrious making in business and training others, I held classes evenings and weekends pretty much throughout each of those three decades. Believe it or not, when we were building the two cabinets for the Cabinet Room of the White House, I held two classes with 15 students on board who knew nothing of why two stately pieces on support bases were for.

Your future, just like mine, is more a rite of passage into a better understanding of your craft and therefore, rather than over-expecting the premium results the teacher or master always seems to have you see the need to learn by doing. This is not an overnight thing. If we just take our time we will avoid having sensory overload and not fail under the pressures achieving the results we strive for. I liken this to being placed in a manual car with gauges in front to read and make decisions on whilst engaging the gears with the gear shift according to the numbers, using the clutch, brake and accelerator and then steer between oncoming cars and in three lanes on a high speed motorway. Watching the simulator is not the same as driving the real thing even though with 3-D glasses on it can feel close. We might think that we see and feel everything and well we might. That’s not the point. The point is what do we do with all of the information feeding into our brains through our receptors wherever they are? That first hour in the car is soon forgotten as we increase our experience in driving through subsequent hours. Eventually driving becomes as natural to us as walking and breathing. I never question whether my dovetail will come out or if my plane and spokeshave will smooth and shape my coarse-grained wood. I can usually consider other things with my mind still making decisions according to sensors transmitting relevant information to guide me in using my tools. This new-found freedom came to me in my later teens. In the same way I no longer consider how I hold my pencil or pen when I am drawing or writing, I am free to compose and make happen what couldn’t happen without it. My mind is ever-searching the grain for answers and the answers always come in the course of my day.

I always try to encourage my readers to make sure they follow our teaching online because it works so well. These two links might just change your life as they have for many a thousand others who adopted what we teach. The first one is our common woodworking link here. This covers all of the fundamentals and many woodworkers who have been working for decades with machines said this was a game-changer for them. On then to my woodworking masterclasses site for more in-depth projects here.

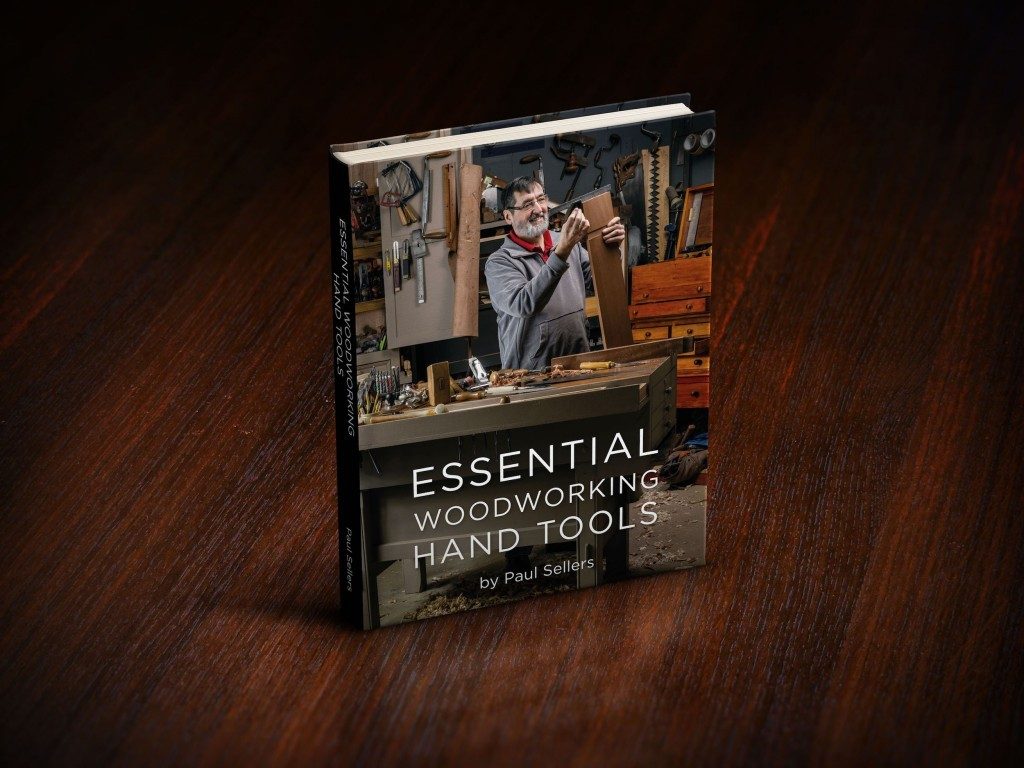

I should definitely not forget to tell you about my book Essential Woodworking Hand Tools the like of which definitely does not exist elsewhere. We rely on the sales of this book to support the work we do and you will probably find, as thousands who own it did, that it is the best tool in the workshop and never too far from hand. One more link and I am done.

There is a great poem somewhere in your words, Paul. They remind me of these quotes. Recover soon!

“If you hear a voice within you say ‘you cannot paint,’ then by all means paint, and that voice will be silenced.” – Vincent Van Gogh

“I do not think there is any thrill that can go through the human heart like that felt by the inventor as he sees some creation of the brain unfolding to success… such emotions make a man forget food, sleep, friends, love, everything.” – Nikola Tesla

Gosh Paul, you can’t keep a good man down.

One of the issues with gaining experience is that there is so much misinformation on the Web. For example apparently coping saws are rubbish and if you don’t use them as pull saws you will break the blade. Comments made by either those inexperienced with using one or as is often the case they are trying to sell you something that costs a lot more. One of the issues becomes that the inexperienced will believe this and often re-quote it. As time passes this issue will get worse. It needs a lot of Pauls to counteract it.

I love bringing old tools back into use. My most recent project was a number of spoon bits. Do I really need them, no, will I use them, yes, I already have.

As a teenager I never liked hand drills, bought an electric one . Now I have a hand drill hanging near my bench and will use it often in preference. Somehow it gives more “feel” and is often just as quick as a cordless. Although part of that is because its closer to hand.

Take it steady Paul

Get well soon.

Best wishes

Keith

The issue with old style coping saws is that the blade is held in tension and cutting on the pull stroke preserves that tension. Otherwise the blade will want to wander. A similar set of physics is in play with Japanese saws.

I don’t know that you would break a blade cutting on a push stroke, and I understand why woodworkers would want to have a consistency if they are accustomed to push strokes with panel saws, but it would be best practice to use coping saws on the pull stroke if you are able to make that adjustment.

Isn’t it funny that things can come across to sound so factual. And there is no such thing as “old-style coping saws“, BTW. This comment is the limited perspective of an individual which we always allow as a point of view within reason. But it does, in my view, give people the wrong impression. Of course, pull or push is up to the individual and good guidance is truly helpful. According to the comment, the person gives the impression that if you cut on the push stroke “the blade will want to wander.” due to the lack of tension on the saw blade. Now this is not at all true in any way, I must say. But this is the same fallacy used to convince people that pull stroke saws don’t have an equal amount of problems in the return stroke-start point of the blade where the wood can and does very often pinch and/or bind the blade and the thin blades buckle and then kinks as it returns for the next pull. Also, stating categorically that, “Otherwise the blade will want wander.” There is not one shred of truth in this statement whatsoever. So let me say, as a strong advocate for push stroke coping saw working, I have never, in 60 years of push stroke coping sawing, had the blade lose any level of tension in the cut or follow a path that was not directed by my hand and mind so as to ‘want to wander’. You can of course break a coping saw blade whether in the push or pull position––it happens!

And not good information or advise at all here in this: “but it would be best practice to use coping saws on the pull stroke if you are able to make the adjustment.” Again I would say that this seems unnecessary and even somewhat fallacious information. Go for the push stroke and you will have at the very least twice as much good, strong, positive control through the direct power this affords the work: any break out through unsupported fibres on the out-cut will be on the back and you can see the clear lines you are working to on the face of the wood you are cutting into so adjust the blade to suit whatever line you can very clearly see to work to. If I want to cut on the pull stroke for a good reason, and there is the odd occasion when I might, once a year or so, I simply flip the blade end for end and just do it. Nothing to get used to or accustomed to or make the adjustment to. Surely you just do it.

I was replying to Keith W saying that a person giving that advice is ‘inexperienced’, talking ‘rubbish’ and spreading ‘misinformation’. My point is that advice to have the blade oriented ‘backwards’ is a traditional view and there are sound arguments that support it. It’s how luthiers and jewellers do it, and their work is far finer and more critical than anything the likes of us might do. I’m certainly not interested in arguing with anyone about it and my comments were only by way of giving a simple explanation of how that ‘rubbish’ viewpoint might be properly understood. It doesn’t bother me at all if people do it otherwise. But it does bother me that such dismissive language is used, particularly when it is clear to me to whom he was referring.

We can advocate for things without needing to be insulting about those whose experience and knowledge gives rise to differing opinions.

Interested to know who you think I was referring to, as I wasn’t referring to any individual, but many sources, including books on woodworking, where the comment about breaking blades had been copied from one book to another, literally word for word.

When I use a fret or jewelers piercing saw I do indeed have the blade set to cut on the pull stroke, due to the way they are used. But coping saws are used differently. In each case the saw blade is cutting into the show surface so that any breakout from the saw cut is not on the show surface. It is often common for some to confuse the different uses of the 3 saws, or at least how they were traditionally used.

@Keith W I think we need to take some care when we are being critical because the number of content creators devoted exclusively to hand crafting wood on platforms like YouTube is tiny. Unless the algorithm for my account is defective, I get feeds from only eight such content creators, three of whom are East Asians and don’t talk about Western hand tools at all. I’m excluding luthiers and people doing marquetry and such.

It never occurred to me that you we referring to that AI generated stuff that google search throws up. But then we wouldn’t be talking about actual people anyway.

My point wasn’t to tell anyone how to use a tool, but to say that the view about ‘reverse’ orientation is both long-standing and conventional. All my texts, some of which date back to the 1940s, give it. I don’t understand why it is controversial. It’s a strange hill to die on. Personally, I rarely use a coping saw, but I have broken many a junior hacksaw blade, or had the blade come adrift altogether, by being too aggressive on the push stroke (on metal I hasten to add) so I understand where the ‘pull’ advocates are coming from. The mechanical principle is little different to understanding that it is easier to pull a thread thru the eye of a needle than to push it thru. And we are talking about very thin blades.

This would be a good place to remind us about which way the teeth should point for either pushing or pulling the coping saw. I always have to put the blade in and try it. Why can’t I remember which direction?

Put the teeth of the unmounted blade against your arm and apply a little bit of a push or a pull. Of course, do not cut yourself. Just make it gently snag. You will immediately know which is the cutting direction and mount accordingly.

Look at the teeth and you will they are like ratchet pawls. Maybe that will help you? I think you should put the largest toothed saw you have against some wood and gently pull and gently push. Then, you will see how the tooth engages with the wood and you’ll understand the cutting action and see how the steep art of the tooth meeting the angled back makes a little chisel at the tip of the tooth. With that, you’ll just know which way the coping saw blade mounts for your purpose. Hope this helps.

When using a 50 or 80 tpi piercing saw blade I can’t see the teeth without an optical aid, I simply rub the blade against a finger, but carefully!

Push coping saw. But pull fret saw.

I love the phrase “we all were built to make.” I think it says a lot about the human experience. We are tool builders and users from back in the day before we even learned how to use fire. I also believe there is an urge in most people to make stuff and hope the amateurs continue to push for it.

I loved woodworking and metalworking at school, imagine my disappointment when I took my daughter to look around before starting her secondary education. We went into the woodwork room and the only thing remaining was the non-slip tiles where the benches used to be. All the lathes etc. were gone! The same in the metalwork room too. This was over 30 years ago, so the skills gap is more than that. If it skips a generation it is lost…..

Well, it starts at the top with who we vote for, who backs them financially, who pays the education bills and who pays the educators. It all links to economists and consumerism. Of course, it is the people that ultimately pay financially and it is the people who generally have the very least say once unaccountable people implement what we educate the generations for. Handwork no longer pays the bills long term in area of manufacturing except the occasional assembly work which is now mostly a robotically controlled process. As a man called Bob Dylan once sang, “For the times they are a changin’.”

It has to do with economics. If too few pupils sign up for ‘industrial arts’ then the economics don’t justify the expense of teachers, insurance and tools. I’ve always thought that industrial arts should be required for all students for a year in junior high school. It would certainly be better than other indoctrination that goes on then.

Steven, It sad that schools have stopped woodwork and metalwork but it must be relatively recent. I say that as a couple of years ago I picked up a S&J dovetail saw and a few other things at a second hand store. The owner had cleared out a school of its woodworking tools and the stamp on the handles indicated it was about 20 miles from my home. He threw in a box with holes drilled in the top that had been used to house 20 chisels and a few Stanley #4 plane irons, some worn to the point where there was little life left in them. These a re useful for practicing sharpening. All the tools had seen good use but were serviceable after a bit of cleaning. The store also had dozens of metalworking vices, presumably from the same source. At least the tools will continue to serve others.

Keith C

That’s a true treasure trove. I need a vise. If that store were near me (Temple, TX) I’d be there when it opened.

I agree and if for nothing else but to give the children a chance to work with their hands and produce something perhaps for the first time in there life. To see the possibilities and to appreciate those crafts people who do make whether it be woodworking, sculpture, clothing or any other hand made endeavor. and who knows what can come from this exposure, perhaps some beauty, pleasure or peace of mind in the future. It is a shame that such opportunists are overlooked. And not to mention the practical aspects of any such endeavor that are applicable in whatever vocation one chooses, such as problem solving, math, plane geometry and many more. As far as physical education programs in school my area does not have near the presence of when I was in middle school in the 60’s. We where taught sportsmanship, rules and a heavy dose of physical exercise that benefits young people at a time when their bodies are changing to develop muscle, bone mass and coordination and confidence. I can still see coach Rose constantly reminding how we need to get develop strength, stamina and endurance and I for one am grateful for that. But I can also see the look of resignation Mr. Hays face when I tuned in my first hand tool exercise in wood shop, the six squared board, it wasn’t very good but he would be proud of me now.

A quotation that may apply to those of us who take up woodworking in our advanced years and may never achieve any kind of mastery of the art…

“Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree today.”

Attributed, probably apocryphally, to Martin Luther.

A similar quote “live as though you are going to die tomorrow, farm as though you will live forever”.

Paul, I hope you are feeling much better and get much better every day.

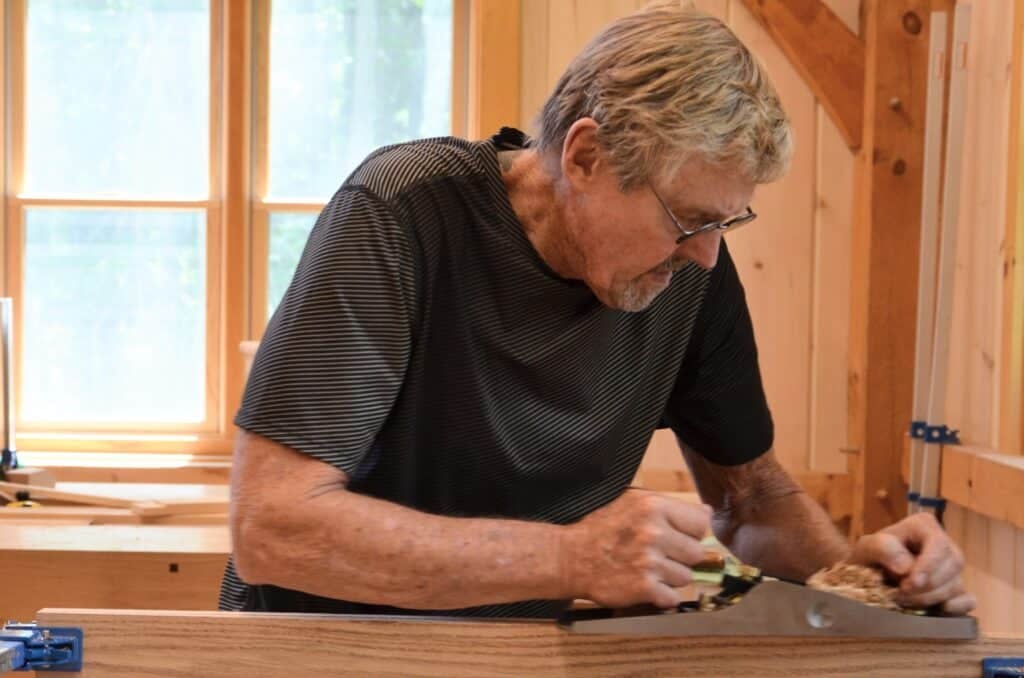

Were those pics made at the school in Elm Mott? I seem to remember such an open and airy space and timber frame construction there, but I was only there once and that was about 25 years ago.

No. Nothing to do with Texas. This was in New York state where I held my US-based classes after 2009.

“Carving spoons as therapy”…

How true. It’s something I do with scrap wood. I make salt spoons which are very traditional where I come from (Scotland) where kitchen salt was kept in an earthenware pot called a pig. Still is in my house. Can’t keep a metal spoon in the salt so they were normally wooden.

Nearly anything will do. Ours is a scrap of Ash from the handle of a broken garden tool that the postie drove her van over. Should last us a couple of hundred years. I’ve made about a dozen so far and it’s very therapeutic watching the spoon emerge from the wood. I give them away – the value in them is the quiet joy I get from making them while listening to the radio and watching my dog and cat playing with the cuttings.

We shouldn’t worry about the craft dying out. I don’t think that will happen despite the machine world taking over, because the amateurs and lifestylers who genuinely care about preserving the skills also care about passing it on. I teach informal classes on traditional ropework and rigging skills which are always in demand for example.

Just in the last couple of weeks a friend came into my shed and saw a pine blanket chest I’m making. She’s asked me to show her how so I’m trying to teach her the little I know. My friend, Jessica, is eleven years old and has a gift (for context I’m 67). I think she will surpass me easily very quickly so I have directed her to Paul’s masterclasses. But what a delight it is to be able to give her the basics, even though I’m no expert. I like to think she will teach some young people someday long after I am dust and maybe think of me and my shed, and hopefully she will inherit my tools.

Pass it on people, it’s only yours for a little while.

Good to see you back Paul. I hope and trust you’re feeling better.

Rod.

It seems to always be that growth in my making goes hand in hand with growth in my ability to see. I developed the core of my skills with you about 10 years ago and while more refinement is always possible, looking back over my development, I was rarely limited by a tool skill. If a tool juddered or if I didn’t get exactly the cut I wanted, then I could adapt, but this didn’t limit me. On the other hand, if I didn’t understand the artistic component of the work, like how lines flowed through the piece, the weights of elements, and punctuation provided by details, then what I built wouldn’t be satisfying.

Right now, I am trying to do some carving that I haven’t done before. I have been stuck for ages, not even trying to put tool to wood. I didn’t have good photos or samples and, so, didn’t have a 3 dimensional understanding of what I’m trying to carve. Without that, there’s no real possibility of getting the art right. I didn’t really understand this was happening and have just been frustrated not knowing why I wasn’t working, but in just the lasts few days, I found a trove of examples from which I can finally start to appreciate the goal. I realize now that I’ve somehow known that hacking away wouldn’t have gotten me anywhere.

Now that I can see more, I’m excited to go try. When I get to the bench with new eyes and lay hands on tools, it will be just the same as 10 years ago….sharpen, feel, listen, and smell. I confess, though, that I don’t have the utter confidence in my ability with my tools that you describe. There is still some struggle, at least a times. I sometimes wonder if one aspect of apprenticeship (ignoring all the floor sweeping) is repetition. My whole life number of roundovers is likely a fraction of what you did as an apprentice nosing stairs in a few days (if I recall one of your stories correctly). I suspect the basic hand operations with planes, saws, and chisels were repeated by you so many times by the time your were 18 (maybe 15?) that I’ll never even catch up with that! But, it doesn’t matter, really. Like I said, it is seeing and the art that seems to matter for me. I can work with the tool skills I have and, when I can’t, it usually means I need to sharpen. Thank you for your teaching!

Ed,

I didn’t learn to really “see” until I had done some work on learning to draw. It also requires practice, but two of Betty Edwards’ books, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, and Drawing on the Artist Within, have been a HUGE help to me. I’m still working on it. Her messages are very similar as Mr. Sellers’ though she says it in a different sort of way that meshes with him and I found her a little more explanatory and thus easier for me, anyway, to understand and incorporate into his observations. I think both of hers are still in print but I’m sure they can be acquired as used, also.

I wish we could start a class like this in a very labour intensive but skill deficient (amongst the vast younger generation) work force country like India. Any ideas on how to kick start this would be invaluable Paul.

Not exactly classes, but if you google e.g. Tools for Africa you will get ideas. These organisations have been around for a long time, so I would guess training goes with the tools. But it is many decades ago that I was involved, so I don’t know what happens now.

I came to woodworking at a late stage (64). One of the things that troubles me is the wood I waste as I’m learning. I seem to be better at making shavings and sawdust than usable pieces. Some of it I am able to salvage if it is big enough, but I wonder what to do with the rest. I don’t have a wood stove for burning. Do you have any advice, Paul?

In watching each one of my children come to read I always felt like I was watching a miracle happen where the ununderstood became the revelation they each needed to understand. As the walked into the letters and then the formed words they owned everything. i think this to be the same in woodworking and all other crafts. Owning words is to enter into a relationship with communication.

One of the best uses I have for my offcuts and shavings, are making food on our fire pan. Especially bacon cheese sausages! 🙂 You can buy a ready made fire pan, or you can get hold of an old water heater with stainless steel and use the water tank.

As for wasting wood: I get where you come from, but wood does indeed grow on trees. 🙂 That being said, I have studied a few logs before I tossed them on the fire…

Deciding what to throw away and what to keep is perhaps one of the bigger conundrums we as woodworkers face. Even the smallest piece of gash finds its use at some point! But I have decided that my scrap bin houses what I need when it comes to small bits and pieces, and when I empty the bin it won’t take long before it starts filling up again.

Starting out, I kept almost every piece. Now I only keep pieces large enough to be useful for a small box at the least.

Shavings and wood dust can be used in gardening, in compost or as bedding for animals. I use the content of my dust collector to improve the content of our warm compost bin – all our food waste goes into it, plus wood shavings/dust and garden waste. Makes for very good soil for our vegetables!

Hi Paul

Good luck with your recovery.

I was wondering if the plans for the coffee table in the above photos are available anywhere.

Cheers

Garry