On Fractured Cutting Edges To Edge Tools – Part I

My thoughts are these. I am afraid we do tend toward living more obsessive lives thinking it’s this or that that makes us good craftsmen and women when in actuality most woodworkers we know don’t earn their living from the work they do in woodworking. This strange condition has created an equally strange dichotomy that then directly influences how we prioritise what we do to be woodworkers. If for instance we are 55 years old and retired with a half decent pension we might spend half a day sharpening a few chisels and know that there are no real consequences that affect other things and in those few hours we simply enjoy the freedom from the various constraints we once had to live with. On the other hand we might work two jobs, have a spouse and kids to be with during non-work time and want ensure everything is done to maximise efficiency. Our personal circumstances are all diversely different and so too then the criteria we set ourselves for working wood.

One thing I see is that somehow, often, we might find ourselves proving to the rest of society that we are not just, well, ordinary when ordinary is actually a good place to be for any artisan. It’s respectful and honest, open and transparent and modestly humble – hopefully anyway. When you meet a true craftsman it’s almost always very humbling to watch him at his work. You always feel as though you invaded his or her workspace, albeit unintentionally and quietly. Very different than with entertainment guru woodworkers. It’s really a very rare experience if and when it happens to us and we treasure the moments. I suppose my thought is that we should leave the super-manhood, super-womanhood to politicians and actors, one and the same often, and get on with what we feel called to do with our hands. Some people say, “Just do what your passionate about.” Well, that’s not really always too realistic and it’s not so easy in today’s culture because it takes more a made up mind, not passion alone. Being passionate can be one of the ingredients to driving an issue, but not the whole and it doesn’t often pay the bills. People who say follow your passion should possibly review the word and reconsider whether determination might be better, or convictions or dare I say it without sounding old fashioned, your calling or vocation. Being practical does fit too and that’s what being a craftsman is about much of the time; resolving different materials into creative pieces to wear, sit on, sit at, lay on, lift from, place on and even ride in and fly in or listen to. Of course the list is unending. Being a crafting artisan is more about honesty and integrity than being a business person or a smart alecky bod trying to sell something only to make money and building a bank account. We artisans, we’ve mastered our craft and in addition have speculatively invested much time and energy and finance in our making and now we must sell or starve. We stand in the freezing weather and conditions no employee would for hours and days to make our business work. We’re not born salesmen but we must sell what we make. We didn’t make a hotdog from a can or flip a burger and add mayo and mustard and a piece of lettuce, we made something with our hands we feel has real value. We’re not managers but we manage. We do these things without a contract of employment and with no job description mostly because no one else could, would or even should do it. Craft shows tend to have a large percentage of ‘here I am, entertain me between meals’ people. They’re not usually looking for furniture or a hand made violin but interested passersby. I say all of that because somehow we crafting artisans, whether arrived or on our way, have started to become increasingly more fanatical about sharpening and flattening our edge tools than actually mastering craft skills. Somehow it’s become something of a platform for performance and this leads me to what I want to try to help people see.

As I have said, we have become something of an obsessive bunch when it comes to the different elements of working wood; sharpness has become more and more obsessive. Now we are not talking about the violin maker seeking sharp levels for clear tone from the wood and who uses wood so soft, unsharp gouges and planes would bruise rather than cut the fine surfaces he strives to achieve. His standards parallel the levels needed for severing tissue by the surgeon’s hand, not the bench joiner chopping mortises and cutting a few dovetails.

It’s unfortunate that since the demise of ordinary craftsmanship we now turn to guru wood writers and not wood-wrights. Woodwrights are no longer there to give us our information of course. It’s true too that the sources of information become more and more questionable. Three recent sources of information teaching on sharpening techniques I tracked back to tool catalog and online sales people selling products for sharpening. Most of the information they have is not new but regurgitated. Each phase of sharpening change marks another saleable product and so we see Japanese water stones added to carborundum stones, Arkansas stones and Washita stones and then came diamonds and abrasive films, diamond paste and flattening stones. The list goes on.

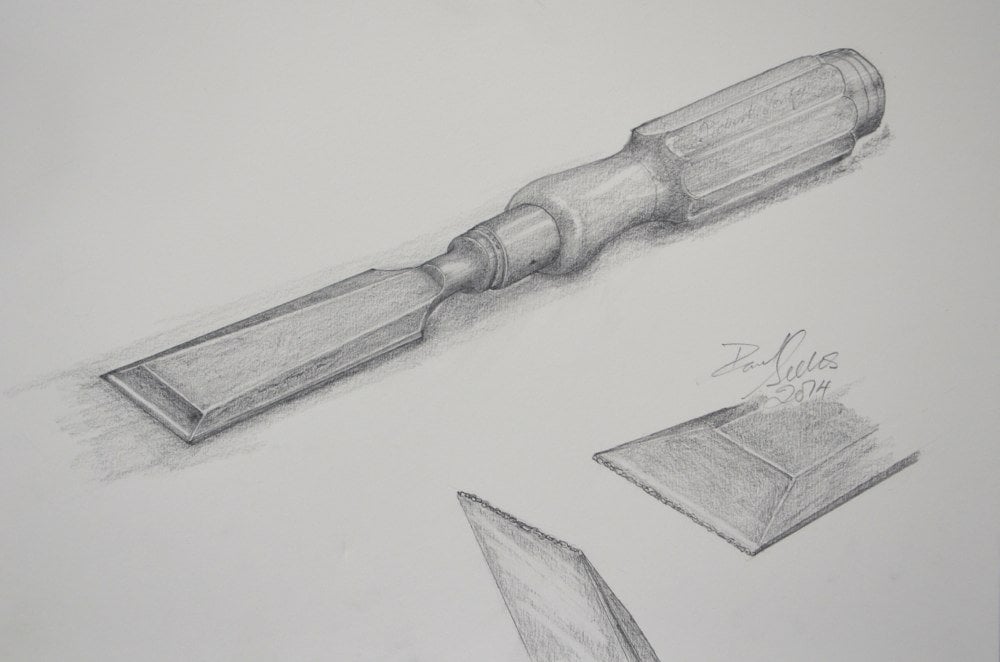

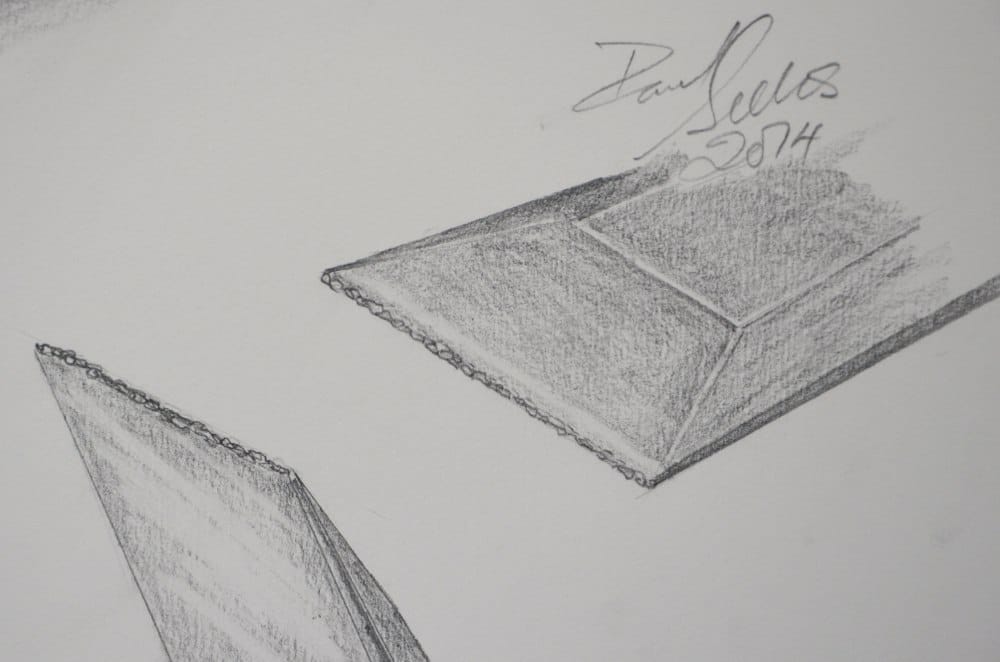

We have survived the different gospels of scary sharp and micro-bevel methodology and are emerging to this very simple reality. As long as you start the cutting edge somewhere around 30-degrees and polish it out it will cut well. If you you sharpen to around 1200-grit it will cut most anything you need in woodworking. If you sharpen to a polished edge of around 15,000-grit you can slice the most delicate of materials effortlessly, but 98% of the time that’s far from necessary. What am I saying? I’m saying that we generally sharpen to task but often sharpen to a higher level because it’s not much extra effort. We all know after a few efforts at sharpening that the greatest effort comes at the start of the process when we have to regain ground to get through a fractured and dulled edge and back to a productive cutting edge. That said, it’s not a big deal, just a few extra strokes on the coarse diamonds gets you there. So, if that is the case, why do we sharpen to higher levels than are usually needed. Well, it is a fact that the more polished the two plains forming the arête for a cutting edge are, the sharper the edge is but the stronger the edge is too. As I said, the extra effort is worth the work because it’s so quick and effective. It’s not so much what we do to the edge to establish it but what we do to the edge after we have prepared it for work. Taking the chisel to the surface of the wood to work the wood begins an immediate process of edge reduction we now know is edge fracture but was once called wear. No matter the steel, edge fracture occurs at some level but some steels fracture more readily than others. What we often do not realise is that it is impossible to find a steel that both takes and retains an edge and at the same time has a level of durability we can rely on forever. All edges wear away by fracture and constantly need restoring. Not without getting into samurai sword making for ordinary work will find an edge retaining steel built to last more than a few hours. In the everyday of life, as a woodworker, we must understand that as soon as the chisel or plane is presented to the wood, edge fracture occurs to some degree. At first the edge fracture comprises usually small amounts of break out and breakdown. That is, in fractions of a second, within the first strokes and chops and pares in the wood, the edge we perfected has now been reduced. Surgery is no longer possible. But, in reality at the bench, we actually rely more on this edge-fractured edge to give us an actual working edge than we do or can the sharpest edge. The opening fracture is very small. Tiny. It is none biased in that it comes from the 30-degree corner we formed not the two facets as such. The facets are both strong and supported but not so the edge itself. The edges always fracture and guess what? It doesn’t really matter. In fact, in the imperfect world of sharpening we might want that to happen. In the imperfect world of sharpening we might even want the softer steels of O1. O1 has good edge retention, strength and durability rolled into one steel type. In the imperfect world of sharpening we can indeed rely on this one thing happening. Edge fracture does in fact give us the most practical working edge for most of our work. That said, continuing edge fracture results in a dull or what we used to call a ‘thick edge and we must constantly refresh the edge to continue our work. This week I did some tests on different steels old and new. It’s not at all scientific but the results did show that we do in fact compensate for edge fracture in the day to day of real work. Part II in this will be out tomorrow, to give you time to digest, so we can look at some of what we found.

Paul,

All so very true. Since the rebirth of woodworking as a pastime, if you will, from the late 70’s, both furniture making and turning, this whole tool industry has exploded, and never more so than with the growth of the internet.

There are only so many times you can reinvent the wheel, a chisel is ultimately just a chisel, so things have to be taken to ever more ridiculous extremes. Like sharpening. It’s become an international industry in its own right.

When I first started woodworking at 11 my uncle made me a pole lathe and taught me how to turn beads from laminations of various woods. My parent’s next door neighbours ran a market stall 6 days a week and used to sell pretty much everything I could make. I did it all with one roughing gouge, one spindle gouge and a pretty dodgy looking parting tool. Sharpening was done on a 6×2 India stone, which I’ve got sat in front of me now. It’s dished like you wouldn’t believe, but it did the job and kept things sharp. No grinding, no jigs. I own them both these days, but it’s such a fallacy and such a shame to see people misled into thinking that you’re almost not worthy if you don’t buy the latest fangled whatever, without which you’ll never make anything worth a second glance.

And all the while this snake oil salesmanship replaces true skill and understanding.

Jon

Just to quote Paul, “how sharp is sharp?”

Did Stradivari possess a man-made japanese waterstone? Probably not.

Did he have sharp tools? Obviously (we can hear it).

Do we need such sharp tools for cutting mortises? I don’t think so.

Jens

Paul, I came to woodworking in a different way. I did have woodshop along with mechanical drawng in Highschool.

In my early teens I became heir to shotgun used by 3 generations of family hunters. The buttstock was wrapped wit friction tape, under which I found two steel plates and bolts holding the stock to the metal parts! Under the tutoring of a local gunsmith. My love affair for stocking shotguns & rifles began. From 16 years of age to my early 60’s I made stocks for myself and uncountable others. I have begun to turn to handtool woodworking and find it as satisfying as the looks of those having my stocks. At 70, the pleasure is still there,but I no longer do stockwork for sale, with no regrets.

The next question is – how flat is flat?

I realise that we want the sole of a smoothing or jack plane pretty well flat and without major imperfections but do we really need to worry about the odd thou? Until I came across articles and web sites discussing getting plane soles perfectly flat it never occurred to me that it may be necessary, certainly my old woodwork teacher at school never mentioned it. And, as for sharpness, I still remember him sitting in front of an old whetstone wheel sharpening chisels and stropping them on the palms of his hands – job done!

We’re working in wood here – a natural material that shrinks and swells with changes in temperature and humidity.

One of the criticisms levelled at me in my apprenticeship is that my chisels aren’t “Sharp enough”. I’ve had people (who were supposed to be training me) come looking for something to criticise and when they were stuck for something, checking the chisels and tutting at me. That the chisels do their job perfectly well doesn’t seem to matter: it wasn’t sharpened on a machine, therefore it isn’t ‘properly’ sharpened.

Only a few more months to go…

There is a jealousy in teachers and trainers you must watch out for. You get it with bosses, overseers and managers too. Jealousy is a wicked, wicked characteristic. Pay as little attention to them as you can without jeopardising your situation until your training is done and then, when they deem you qualified, change the future for others yet to come

Thanks Paul. You’ve described exactly the situation I see with the jealousy: people in a small world whose satus depends on them being the ‘experts’ in their field.

Your advice is also what I intend to do. It was my goal before I began the apprenticeship and every attempt to break the ‘silly dream’ made it stronger, because it proved how important it is to do something different.

Not easy though. Still, I only have to survive until February the second…

Yeah, hang in there. Some people are threatened, some challenged and some are just sef-powered dynamos where its all for them alone and they think the power of life begins and ends in them, its mostly about insecurity that’s all.

Paul,

I just discovered your blog and I am enjoying the reading. I would venture the jealousy is really fear of not getting what I want or not keeping what I have.

I used to shave with shave cream and a multiple blade razor. Every few days I would start with a fresh blade, every few years I would buy the newest shaving gimmick. I was ignorant and life was good. Finally through experimentation brought on by boredom I found a better way to shave. I no longer use shave cream and now my blades last several months instead of a few days. What happened? When I came of age my father was busy earning a living and never took the time to teach me how to shave. Consequently I learned to shave by watching TV commercials. That’s right, because of a breakdown in teaching I was left at the mercy of today’s most prevalent and persistent teacher, the television commercial to learn the basics of shaving. This is a common yet subtle tragedy.

The point is, if we leave the the teaching to the media all we do is get dumber and spend more. Instead why not teach the best of the old proven way, add a bit of the new way (like diamond stones) and make real advancements that improve your life not just change it.

Possibly your instructor is themselves being marked down because his reports are to thin or his pencils to fat? Have some sympathy for those who criticize you in such a way, they have the difficult task of finding fault in someone who has surpassed them.

Hello Terry, and thanks for the encouragement. My ‘instructor’ is the owner of the company where I’m an apprentice. As I said in my reply to Paul, I think there are many people locally whose status depends on being the ‘expert’ in their field, so anyone who comes with different ideas is a threat…

Some time back I was reading what I think was a woodworking blog and the author commented that sharpening had somehow become more of a fetish for some rather than a means to an end. I think that line stuck with me because I was headed down that path.

I do oversharpen for most tasks but for good reason. The first is I don’t have 50 years of woodworking experience to draw upon to tell me what’s “sharp enough” for a given task. The second is it’s so easy to get those blades hair popping sharp that I wouldn’t gain much by stopping earlier.

Just lately I’ve observed that “edge fracturing” issue Paul talks about without realizing that’s what was happening. I start off with my hair popping chisels but after a bit they will no longer shave hair. Rather than resharpen from scratch I keep my strop near my work. If 10 or 20 strokes witll bring back a shaving edge then I’m good to go. When that won’t cut it I know it’s time to retire to the sharpening bench and shape a new edge.

Thank you Paul for the explanation of what I was observing.

John- Maybe you have the problem I have. I sharpen as Paul teaches, but often after a couple of paring cuts on end grain, a bur reappears on the edge and cutting becomes poor. What I do now is, I sharpen as usual, then give one mallet whack with the chisel on a piece of scrap oak and feel for a bur. If one comes up, I return to the superfine and take just a few light strokes, strop, and then whack the oak again. If no bur comes back, then the chisel is ready. Paul has watched me sharpen and didn’t find fault (actually, he told me the scrap oak trick). Maybe I’m not strong enough on the strop or go too long on the coarse. I’ve never figured out why I get such a persistent bur, but this fixes it. Some day, I won’t need this crutch.

Ed I have had something similar happen and I came up with my own trick to deal with it. When I get done sharpening my last step is to slice once through the plywood edge of my sharpening bench. I’m not taking any wood off, just sliding the edge through the plywood and leaving a little groove. It takes off what I used to call the “wire edge” but is probably just left over burr that is temporarily standing straight out from the blade so it’s hard to see and feel.

I’m not having a problem with my sharp edges per se. What I have trouble with is confidently determining when a blade is “sharp to task” so I compensate with the method posted above. I figure too sharp is better than not sharp enough and with Paul’s methods it only takes a couple of minutes to keep them that way.

John

Have always taken the burr off by stropping for want of a better word on the Palm of my hand as I have always seen my dad do though I suppose this could go wrong always worked for me,maybe leather with no abrasive would be a safer option. I find Paul’s method of sharpening difficult to gauge as the edge is so fine. I suppose before what I was actually feeling was micro serrations (around 600 grit) though it is when presented to wood deffinately sharper cheers Paul

I did the same for a long time but then the sharpening levels went higher and I felt it was too dangerous: especially for those watching who thought it was best. When you use compound on a strop there should be nothing left on there.

This reminds me of another metaphor. Back in the late 1960s when I went to artillery school at Fort Sill, OK, some students would ask what difference a mil or two would make in our calculations. To a gunnery instructor, a mil or two would never be satisfactory. Then, we’d be reminded of the (supposed) goal of the the gunnery department: bean the lead mule in the pack train off the head with an unfused round. (A pack train in the open being the traditional target at the Signal Mountain firing range.) I guess the lesson is to be as dead-on as we can be in our work while not becoming obsessive about it where it doesn’t really matter–craftsmanship being the wisdom to know the difference.

Excellent post, you say things that need saying, and this one was a stellar example. I especially enjoyed the line about scary sharp and secondary bevels!

I always enjoy reading these older posts … I was never much of a sharpener, mostly because I didn’t really know what the heck I was supposed to be doing. As I have gotten better at the task it has become a bit easier. Wading through the hype and bull puckey has been difficult, which is why I find myself continually rechecking the one resource I know who is out there trying to dispense this knowledge with honesty and wisdom – Mr. Paul Sellers and his small group of hard workers. I guess it usually pays to take advice from somebody who has “been there and done it” (in Mr. Sellers case it seems … usually twice). The tool sellers and manufacturers do indeed tend to muddy the waters and want us to spend a fortune on a pile of gear and machines to do even the simplest tasks – often times because few seem to remember there was at one time a manual or hand tool option that worked easier and just as quickly. Thanks for keeping these older posts just to remind us when we do tend to wander off the path of reason and the efficient way!