Slopes

Slopes have purpose and meanings we might pass by and take no stock of in our passing but to designers, they are as highly relevant as arches to openings for doors and windows, to tables, chairs and a mass of other furniture pieces. Whereas the core reason in both arching and sloping is not for design decoration per see, they are still features without which some things would function less equitably, sag, collapse, and weigh in in some wrong way. My slopes came this week in a medical clinic waiting for my annual blood tests and then in a bookshop. The former was in a sloping window frame, the other in shelves sloping slightly front to back to slide books to the backs of the cases. They seem small things; one was to take the weather away from the sliding sashes giving the windows a rain-free and unimpaired view from inside, the shelving used gravity to locate the books within. In both cases, pun intended, the designers used gravity as a feature to the designs. Though over a century apart, I thought how useful is that design is not dead and the human mind is often thinking up new ways for things to work, to be benefited by natural influences like wind and gravity.

This sloping window faced the prevailing wind which drives the rain towards the window so the architect came up with the idea of a slight tilt for the windows and I thought to myself ‘That’s clever forethought!’

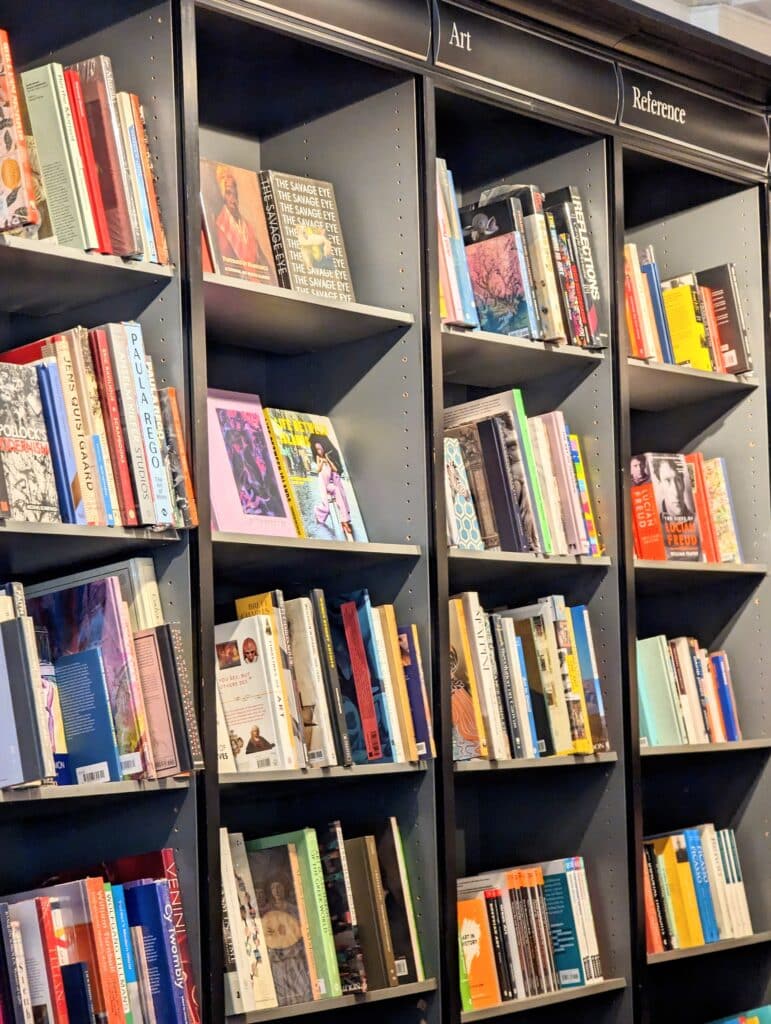

Such a minor slope but with a major impact on the presentation of books when the flat face needs to be shown for selling or promoting. The simplicity of dropping the back hole a notch took care of manufacturing issues so the shelves can be used level or sloping according to preference.

In the distribution and transfer of weight, arches really know no equal. They have lasted millennia and whereas concrete in different forms also dates back millennia, the reinforced concrete is relatively new. By using reinforced concrete we managed to replace most stonework to achieve similar clear spans with minimal support via slender columns. In our world of woodworking and furniture making we use arches to lighten the appearance and the physical weight whilst ensuring no compromise takes place around the jointed areas of say a chair or a table. Some pieces with parallel rails look heavy and clunky and that is because they are. We can reduce the weight of a piece by a good percentage and that is why they were used so much on pieces we move minute by minute; chairs are working pieces and good examples because no other piece of furniture is subjected to more abuse than the humble and overworked chair.

The backwards slope of a book shelving system will, like arching in furniture and buildings, go largely unnoticed yet they stop me to take in proportions and shape all the time. You cannot walk past almost any building in Oxford without encountering many a dozen in a single building and therefore see just how important arching was to stonework and therefore the woodwork housing windows and doors.

Less usual archways were used to the same end of spanning wide areas and expanses. Elliptical arches always add an elegance no matter whether it be a building or a piece of furniture.

And then there are the frames of Thonet-style chairs below where bolts and screws attach the components as third-party fixings. In his displacement and the replacement of all joinery and the tedium of joint making, he came up with one of the first mass-production chair designs and at the same time came up with a design that considered lightening the bulk and weight of costly distribution and packaging to deal with the bulkiness of these pieces. In the lightweight framing, joinery itself would severely weaken the extremely lightweight components his chairs were to become known for.

Hello Paul,

Another interesting post on your blog. I too am forever looking at how things were designed and made, (not always at the appropriate time and place) and I find myself making a mental note, or more reliably, taking a picture on my phone.

The Thonet chairs are indeed a remarkable design, and it is the use of steam shaped wood that I find interesting. I’ve never done any steam bending, but believe that it is possible to do so in a home workshop/garage situation. Is there a possibility you may incorporate such a feature in the future?

Steaming can indeed be done at home. If you’re just doing small pieces for things like chairs and just want to try it out for experimental purposes, then a wallpaper steamer works well, alongside one of those plastic vacuum bags that you can buy for storing clothes and duvets and things. The benefit of the bags is that you can bend, clamp and steam at the same time because they are both malleable and see-through. The better (more expensive) bags can be re-used too as they’re usually hard wearing enough to not get holes in. That said, there may even be a product that does this better these days, I’ve not looked. If it’s something you intend to do more often, than a simple steam box is likely a better option.

My family had a business on the Thames at Hammersmith and I on several occasions helped my father put oak ribs in various skiffs and dinghies.

The oak ribs would be steamed in an old tube into which the steam was passed then bent into shape, drilled with a hand drill, a copper nail was banged in and a rove ( washer) put on the nail which was then cut and flattened with a ball pein hammer.

No wonder no one repairs wooden boats anyway, sad though.

– About arched woodwork windows housing. People might be interested to see a video (hand tools only) about rehabilitating an historic building. Search for:

“Handhyvlade svängda profiler – ett gästhantverkarprojekt” It is in a Nordic language but the the technique is clearly shown. Look from about 13’30”

It shows a technique to make an arched panel. The technique starts from a straight flat board but doesn’t waste wood.

Sylvain,

Thanks for the heads up on that wonderful video. My Norwegian is non-existent, thanks to the population’s perfect English on every visit I’ve made, but the process was still clear and enjoyable to follow.

Thank you.

Rico

Interesting to slope the windows in. Logically I would have designed them sloping out. I would think water will collect at the base of the window, rather than being directed away. And if this idea was a good one it would have come into common use years ago. There must be a steeper slope to the outside sill to deal with this. In fact, why slope the window at all? The builders must have cursed! What is the logic behind the reverse lean? I’m confused!

I think it should be obvious, really. The rain never touches the class or the frame. I’ve been there often enough and never seen the glass touched by rain. And why on earth do you think the builder would have cursed? It’s simply a question of a plumb line mark and a measurement. Your supposed logic for sloping the bottom out is completely illogical, I would point out. The stone cill (US sill) slopes away to the outside so no gather and collecting of water as the water cannot drain down the window to puddle anywhere. And just because it was innovative where I live it is not necessarily going to be adopted in other climes of the world.

Paul,

While the sloped window is effective, it appears to me that an architect designing building windows in a climate that has a lot of rain (the windward sides of Hawaii) should design with sufficient overhang of roof or lintel to allow windows under most wind conditions to not be touched by rain. The same is true in the hot dry Southwest of USA to keep the sun out of doors and windows on the sunny side of a building. Having to add an awning only admits that original architect did not do an adequate design.

Isn’t the wrap-around porch in the Southwest USA such a design? Yes, it would have been good to do the same in the UK but we like bright natural light in our homes. A decent wooden window will last a couple of hundred years if it is maintained well. Traditions are hard to change. Plus, don’t forget that many designs are built to be replaced intentionally. that’s good for the economy even though it is indeed a false economy in the end. Everything in life is built around consumerism and its bedpartner economy. Building fashion demands is about built-in disposability by throwing out good things because of something going out of fashion rather than wearing it out. Also, I do think that people’s perception of English weather is somewhat skewed even by Enlish people; it might surprise you that the Texas average rainfall in a year is 27″ whereas here in Oxford it’s 26″ Remember, I lived half of my working life in Texas..

I would like to suggest, as I am sortof living in Mississippi where it rains every afternoon and more on Sundays, that the downsloping frame and downward sloping base is brilliant!

* Wish they did that on my currently rotting out doorframe (despite an overhanging copper lintel) that I don’t know how to fix. Suffice to say the water landing on the driveway splatters up against the door, which eventually rotted out the the frame. And I haven’t yet sprung for one of those vibrational cutters to slice out the nails, remove the doorjamb, measure all the dimensions, source new matching wood longer than 7′, and reinstall a perfect new jamb.*

Edit: sloping the other way might also work. I will test it next time it rains. (aka tomorow most likely).

Also, anyone who knows how to rip out and replace a door jamb feel free to instruct me on that.

Sorry. I guess I shouldn’t have posted a stupid question. My fault.

There are no stupid questions.

The slope will have the added advantage that the window will not get as quickly.

We live near the ocean and have wind-out windows. A window that is open (ie top slopes back towards the house) will get dust and salt caked on its surface much faster than the glass keep in the vertical. A pane of glass sloping out would reduce my cleaning chores.

That was – will not get “dirty” as quickly.

Round and elliptical shapes fascinate me. The onion domed architecture in Russia is breathtaking and devilishly challenging to imagine how they built those roofs with hand tools. I struggle with straight lines and cannot conceive of how hard rounded shapes must be to work. They’re worth it regardless…magisterial!

I saw a YouTube video of an old fashioned barrelmaker. He looked like Paul but with fewer teeth! He’d grab a dry hunk of spruce from his woodpile and split, shave, and make the steel straps and nails and fit the barrel together on an old mountain farm. Then they’d put pickles, cheese, bran, milk into the barrels and it would last for a long time because it was airtight!

There was another video of a Swiss laddermaker, also using spruce for the long pieces of a wooden ladder and hardwood for the rungs and spacers.

That would be a great WWMC project: buckets and barrels! We already have an excellent ladder video!

Since only the window sash and track are sloped, not the rough opening. The weights should have no problem in the pockets. I would think the sash cord pulley needs to have sides tall enough to keep the cord from riding out, but that shouldn’t pose a problem.

Paul,

I apologize for the diversion, but I am amazed at the complexity depicted in your 5th photo. The arch is elliptical, but only subtly so and yet it contrasts nicely with the circular elements of the fleur-de-lis above it. And while these are symmetrical in 4 lobes they in turn contrast with the 5-lobed windows in the door head below. Then there is the carefully smoothed stone elements framing walls of rough natural stone which, at least on the right hand wall are interlaid with smooth rectangular blocks which nevertheless work because they are laid at haphazard angles that break up the regular linear joints.

Then there is the dichotomy of these legacy architectural elements contrasting with modern glass doors that allow visual passage to the interior while subtly reflecting the exterior. Over this ancient portico a more modern electric light has been retrofitted to illuminate the stoop but it still somehow fits, perhaps because of its low profile and its simplicity.

Finally, the artist photographer self-inserts his reflection in the right-hand door pane while still permitting us to see into the lighted interior through the left panel. You could use this photo in about 100 different articles and perhaps still not plumb it s depths.

Thanks for sharing!

Hello Paul,

How do people provide comments on your writings when I have not seen them?

Mike Norris

San Antonio, Texas

If my writings have not been seen then they are not public and not for comments, I suppose.

Hi Mike,

if you mean past posts that you didn’t get a notification for, you should be able to see them in the Archive: https://paulsellers.com/archives/

Paul,

I enjoyed Gordon’s analysis of the 5th photo: a picture is indeed worth a thousand words!

My apologies for this interjection, but for the sake of accuracy I must. Some 55 years ago I worked as a draughtsman in my uncle’s architecture and he was a real stickler for accuracy.

This is not an elliptical arch as stated in the caption – it is one of the pointed arches, of which there are several, some generally called “gothic arches” but not all. An elliptical arch has its flattest part of the curve at its center, whereas this arch has a definite point at the center. Also, the windows that are referred to as “fleur-de-lis” are actually called “quatrefoil (4 lobes) and “cinquefoil” (5 lobes).

Thanks again of reminding us all, how important detail should be!

Paul , re. your photo of a sash window, my understanding was that the downward-pointing horns at the lower corners of the upper sash were only introduced in the Victorian period to strengthen the corner joints when they began to be able to manufacture very large panes of glass. As people banged the sashes up and down, the weight of the glass would break the wood below the mortice at the corner. Georgian sashes, having small panes and glazing bars, did not need or have these horns.The lower sashes of course couldn’t have them, which is why old-fashioned ironmongers sold those L-shaped bits of steel that you screwed onto the corner as a botched repair.

The upward-pointing horns on the lower sash serve no purpose (unless purely aesthetic).

These sashes look relatively modern (possibly double-glazed?) It looks as though perhaps they are two identical sashes and they’ve just mounted the lower one “upside-down”.

Incidentally, I’ve never heard of sloping sashes. Are you sure it’s the window that’s sloped and not the bit of wall forming the side of the opening to the right?