The Evolving Toolbox II

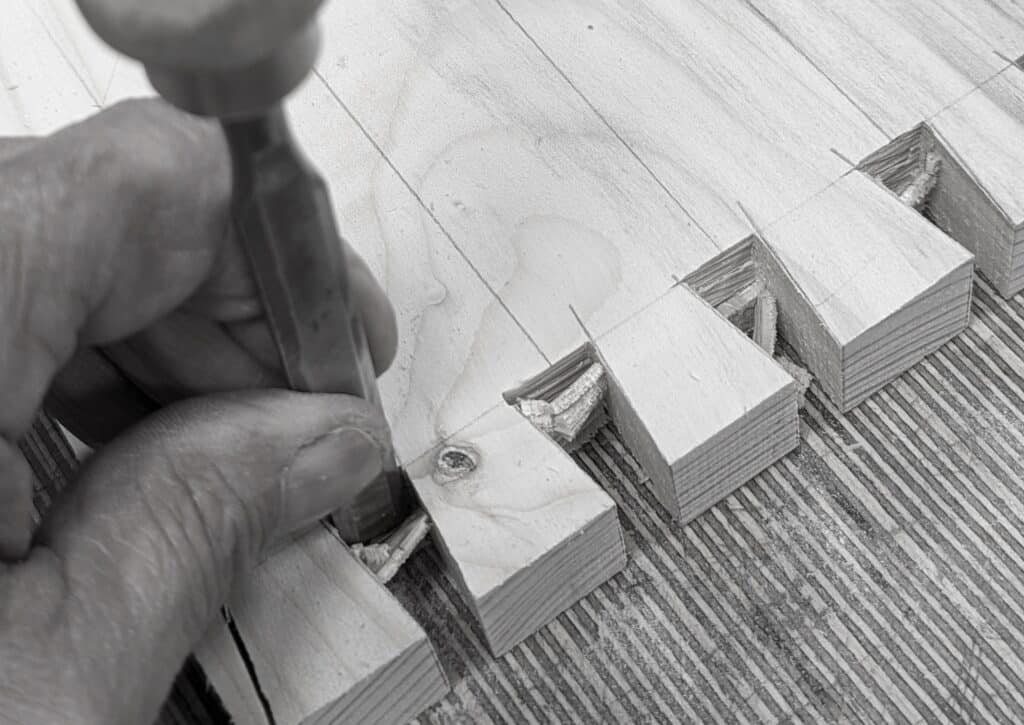

It was the tap-tapping of the tails into the recesses between the pins with the end of a one-inch chisel I remember the most. George had shown me this but did not leave it there. He’d explained Newton’s Third Law that for every action (force) in nature there is an equal and opposite reaction. When pressing with my then thin, unmuscular thumbs and fingers the tails no longer moved further in to bottom out, I needed a little extra and a chisel was always close to hand and a good choice. As I tapped, the inserted tail wood exerts pressure and by doing so an equal and opposite pressure to counter mine caused the tails to deepen and almost magically pull themselves into the recess. The tap to each tail sent the pin wood into and between each dovetail just a fraction ahead of whatever was on either side. I could both hear and feel the ‘pinch‘ of tightness as I traversed the expanse of dovetails going first from left to right and then back from right to left. It wasn’t what everyone insufficiently calls this fun though, it was the sort of frivolous triviality that lessened what was in reality more a deeper sense of pure exhilaration. To describe victory of this or any kind as mere ‘fun’ makes it so much less than the realness of it. This very specific and wonderful worked-for victory told me that I could and would always make airtight and watertight dovetail joints to equal those of all of the men in the workshop who bit by bit taught me and were now hovering around to look over my shoulder. These men never criticised me unless I needed it and by that I mean they did not take any talking back or beligerence lightly, but they did critique my work and by this I grew. Big difference.

I do get why people refer now to more things as fun though. Today, yes, it means entertaining, enjoyable, amusing, light-hearted pleasure and less its original meaning of a diversion, mere amusement, even to cheat or trick someone. There was a frivolity to it that has now been more distanced from its origin: fonne…foolish!

I think this to be the main difference between my working life and that of others in our evloving universe of worklife. Going from school to work at age 15 was indeed a serious step. That culture of maturing in my day seems in many ways to be mostly gone and some of that may not be a bad thing so long as maturing to a place of taking responibility is not neglected. It was always serious even though we did find fulfilment and joy in our work. Today it seems as though maturing has been postponed in many ways and many realms. I don’t see joy and fun as being one and the same or indeed in any way related. As two significantly different conditions of the human mind and being I think now that many mostly choose the term fun as more an all-inclusive expression yet the difference between the two is night and day. One deepens the sense of achievement while the other somehow trivialises it. We no longer use terms like joyful, enjoyment or enjoyable though in my world these describe what I do and have throughout the day far more accurately. In that place, my mid-youth, post-war space and time, there remained something of a certain sobriety in the world I worked and lived in and it was reflecting on this that I found what I enjoyed in the camraderi that has never been replaced. It was the solidity and dependability in an era when I was able to finally dismiss school as more an unreliable place of immaturity to be absorbed into manhood. Those transitional years matured you progressively if you were working amongst those who took on the mantle of maturing you and making you responsibly productive. Those men saw that then as their responsibility even though they would never use such terms or explain it that way. They just assumed it as their responsibility as any mentoring artisan or craftsman overseeing and apprentice should and did.

What was unique about the outcome of this particular and specific dovetail was that I didn’t do it to be approved. These men never worked to be admired or qualified or anything else. None of it was to gain approval because the standard of workmanship was expected no matter what. It was the realness of life I admired and respected and so too them. They, aside from my parents, were the first adults I would associate with on a daily basis and they in turn placed expectations on me that brought maturity out of me and that to a fullness. Even when the men were indeed impressed, along with George, that was not what I sought. I achieved standards that measured up simply because it was the right thing to do with the right and intended outcome. Here, I managed the making of the dovetail using the first tools I had ever bought, owned and used with my own hands. Looking back now, knowing that I have made thousands upon thousands of hand-cut dovetails, and having now reached the age I have working my wood through six decades, it was that first dovetail of quality that raised and set the bar of self-discipline for me for life. I believe it was this that spoke to me the strongest, saying I would never once use any other method for cutting my dovetails. I wanted what I did to be good, of course I did, but what I saw was that the outcome of what I did would indeed, by its very nature, validate me as a capable woodworker in my own right. The lines of satisfaction fell there. By this I would be governed throughout my life.

But, of course, there was too an approval that did come from the men and it was simple and simply put: “Good lad, Paul!” They didn’t dish out compliments easily these men who day in and day out made the wood do their will. They were encouraging me and it was indeed an encouraging thing, as if these men were bonded as a sort of brotherhood with one another to become my true mentors in craft. George passed one of his wide grins from the other side of the bench, leaned over and earthily said, “Don’t let it go to your head. The next three corners will be harder!” It’s a grounding thing knowing where you are in the pecking order.

Making this joint had taken me about an hour. Only one comment from one of the men remained to challenge me. “Should be good. Took you long enough.” George had taught me two things about dovetailing box and drawer corners. One, the joint comes best straight from the saw and should in general need no refining with chisels. Two, they should need no trying to see if they really fit. I recall him raising his voice and asking me, “What are you doing?” I told him I was trying it to see if they fit. His response was simple. “You shouldn’t need to try it. If you’ve done it right, how can they not fit?” He smiled as he said it but then explained that putting the joints together only abraded the meeting faces and so fractured the surface fibres. As I said in the last post on this, I now press them home just to ‘keep‘ them, ready for the first and final glue-up. Of course, we may or often have to dismantle the joints a few times for practical reasons in the making of boxes: working other corners, adding in other joints and such. Just keep it to a minimum and when the box is done, if glue-up is not immediate, leave the joints assembled until you are ready. That way all the components are protected and they are expanding and contracting together at the same rate.

As my box came together the men watched me from a distance. I could tell they were enjoying themselves and delighted in throwing out knowing comments. Generally, they were encouraging my work and that was because they knew I was no longer temporary. The trial for me was over. I’d be staying for the full five years of my apprenticing and the work and I suited one another. Transitioning from the brew boy, errand runner and sweeper-upper to more serious work was steadily arriving. Many tasks came my way throughout the day, much of it tedious and repetitive but overall my course was set. As the four corners of the toolbox were now seated and all inspection by the men was passed I was warned to go less public with my working on it. Though the foreman had encouraged me, he didn’t want me working on it in work time even though I wasn’t. What he wanted was for others to understand that there was no chance of me fudging the lines. I could spend fifteen minutes of my lunch break on it or after the work day if the men were working overtime and someone else was there.

After the box dovetails were finished I glued up the box and returned it to the back of the wood racks to hide it. Bit by bit I had most of my wood gathered. I’d needed the front door frame and panel and the rear frame and panel wood. I’d also needed two tills for all the small tools along with the till bottoms. This last level of accumulating came mostly from offcuts as the parts were so narrow and small.

My personal tool chests have worked fine for me so far though I don’t use them in my garage workshop for my my online work. In most independent workshops like mine where security is not an issue, it’s more convenient to have places for the tools in the open atmosphere. A hundred percent of my hand tools are within a metre of my hands and my vise. I want and need the immediacy of tools ready to go for efficiency in my work. But there have been times, longer periods, when my tools were in more unstable environments and needed bolting down. I designed mine as a furniture-making foundation course for hand tool woodworkers who came to my month-long furniture making courses. In the making of it you have carcass construction, door and drawer making, etc.

My perception of tool chests parallels the emergence of changes in woodworking. Someone commented that their tool chests were ideal for storing the dozen or so jigs they made to go with their power routers. Bulky and blocky, these things litter every machinists workshop. For hand toolists, shooting boards and mitreboxes are the equivalent of ill-fitting equipment.

Going back into the history of woodworking opens the doors of our understanding. By these skirmishes, dipping in and out, we look into the environments of makers in their day. Take the ships carpenter on board the ancient ships built only from wood. The raising of the Mary Rose from the depths of the ocean came about in 1982. I plan to expand things further as we dig deeper into my past. I have more to say on this!

Thanks Paul. Lovely post. Greatly appreciate the time it takes to write something like this.

Your comment of “there remained something of a certain sobriety in the world I worked and lived in” resonated. I worked in the UK in a research lab for two years start in 1996. Frequently after work, we’d go for a pint (I never was a big drinker but if I wanted to socialize, the pub was the place my colleagues went). I recall one of my colleagues, born in the 60s, describing how the UK had changed after the two world wars. The word he used to describe the country was tired (at least that was the one word I recall). I think your words might be a better descriptor.

Thank you, Paul. I have read “The Joiner and the Cabinetmaker” and while it is a very good read, and a fine addition to my collection, there is something in your words that more completely draws me in. How I wish you had a similar publishing. I’ve taken to leaving your videos running for my pups throughout the workday when I am not there. An odd practice, I know, but if listening to you work and speak is so therapeutic to me, then how crazy is it to assume that maybe they will also benefit from listening to your words and be less anxious on their own. 🙂

God bless.

I’ve never really thought about the differences between Joy and Fun but I’ve known both feelings like most adults.

The feelings of joy are harder to explain but are deeper and long lasting.

Joy usually involves some expenditure of one’s energy, time and experience not necessarily for personal gain but it can be.

Fun or happiness is temporary like eating your favorite food.

Thanks for giving us this glimpse into the past, when life was simpler and, in some ways, so much better than the working life of today.

The images are an extra bonus!

I would love to see you write a book solely about your early experience in the apprenticeship program of the trade. Chef Jacques Pepin wrote one about apprenticing as a chef in France – one of my favorite books. Here in the US only a few trades still have apprenticeship programs – electricians, plumbers, etc. I think there’s a lot to be said for that, not just for nostalgia’s sake, but as a viable, valuable path to a productive career.

I think it’s particularly sad that kids these days grow up saddled with higher education debt, an education that, as often as not, has little to do with their final career. And those wild college years are often a sign of not having any roots in the discipline and responsibility of a working trade, without a mentor and role model like your George. It’s no wonder many of the latest generation are still behaving as children well into their thirties.

Like you said – “sobriety.” I hope you will consider it!

I look forward to it. I have made many, many other the years . They always fascinate me

I call your evolved toolbox the Rosetta Stone of learning woodworking. It has a substantial fraction of all the required skills. Mine is in constant use. You can buy shelf liner impregnated with Zerust anti-rust, which is what I used to line the drawers and top.

Ah, the good old days! I think that class in 2012 was the premium of any of the courses I ever designed and taught––and that was the best I think, the venue, the weather, the peace, the fulfilment, the satisfaction seeing everyone load up their projects––Imagine. I proved that inside one month I could teach and train a cluster of ten relatively new and then some completely new hand tool woodworkers what every college course in the world took three years to get through but could never actually teach. They needed long-term bums on seats for years. That was not my way. We made all those pieces. Imagine making a tool chest replete with drawers, door panels with raised panels, and complex joinery thrown in at the backs of drawers that would never be seen but we knew was there for the long haul. How about the coffee table and the then, to crown it all, a craftsman style rocking chair with 48 joints all cut by hand and not a machine insight or needed. Everyone on those longer courses was utterley determined, comitted and dedicated and everyone made the complex, multiproject pieces to build their future on. I just glanced back through those summer images of July 2012 and saw how intense everyone was, Doctors, dentists, engineers. Remember Cynthia, the CEO of the healthcare clinic who brought me a Starbucks coffee on her way in ebevery day? As far as I can see no such course exists anywehere and nothing comes anywhere close. We did have an absolute blast!!!! Just thinking about it, I doubt anything like it can ever happen again but here’s the thing, all of those pieces are available in our online offering plus two hundred more. What we have achieved as the smallest entity online is now massive and there is still only a handful of people on the team. I’m amazed still.

It was a life changing experience. A few other memories include peaceful lunches with classmates and you, getting ice cream many times after class with Ray, and you periodically breaking out in song (often The Beatles) while we banged, sawed, and planed. I still take classes, e.g., for period American furniture, and your lessons are the foundation for it all.

You equipped me to think with my tools like some sketch with pencils. The rocking chair had a lot to do with that. Yes, it has a lot of mortises, but just as importantly, it is a big awkward thing to work on at times, so when scribing the legs to the rockers (as one example) one must learn to saw at whatever angle is required no matter how the work is clamped. The floor, the bench, vertical, horizontal…none of that matters: Just see the line, get your body to where it needs to be, settle the saw in, and go. Developing that ability provided enormous freedom and helped me see that, if I can get a layout line onto the wood, I can probably fabricate what is needed.

I don’t know if I told you, but when I got back home, I arranged some one-on-one classes with a craftsman in VA who was well known as a finisher. I brought the table and chair with me and learned to finish with dye and topcoats. He took a look at the tool chest and said, “not that one, not yet” partly because of complexity and partly because it was pine. So, that became my homework, which I finished soon after to extend my finishing skills. Through this, I learned that finishes are adjusted step by step just like doing joinery.

I think you really have a gift for developing woodworking curricula. It was evident in your first paperback book and DVDs (and I’m sure in your Texas classes, which I know nothing about). Each project had a purpose and the order of projects built up and reinforced skills. Sometimes I wonder if new students facing the Masterclasses might be confused about what would be a good order and selection of projects for getting their core training. I know there is Common Woodworking, but somehow I feel like the question may still be there. There are hundreds of projects now on WWMC, yet a careful selection of maybe 3 or 4 classes after a little warmup via Common Woodworking is really all that is needed to get a really substantial foundation. New students (or old ones!) may not know which to choose.

If you are curious, I am in the middle of making a reproduction of the Duffield longcase clock on display at the NY Metropolitan Museum (Google will quickly find photos). This is from a class I took. We only had about 4 weekend classes during which we learned the structure of this type of clock and received sketches showing moulding profiles and so forth, but a great deal is up to the student to figure out. It is going slowly because I don’t know how to carve, really, and am having to grow a great deal on that front especially learning to see and appreciate the classical idiom. (Not your cup of tea, I realize.) Really, though, 90% of what I need to build this is what you taught me, for which I am deeply grateful.

@Ed and @Paul, I love and appreciate this short stroll down memory lane. That class in 2012 was life-changing for me and amazing in all the ways Paul mentioned. I’m so grateful that I had that chance to apprentice with you, Paul. Also Ed and I have managed to maintain some ties since then which I’ve very much enjoyed, although he’s gone much farther in his application of the woodworking fundamentals we learned in NY. For me and my family, it has resulted in many beds, bookshelves, desks, a few chairs, garden carts, wooden swords, and many hours of peaceful work in the shop with my children learning and doing beside me.

I am so glad it was a positive experience for you and Ed, Eric. I just looked through the thousand or so images to see if I had what it takes to create a How-to blog-post series on making my tool chest. Remember I made one alongside everyone as I always do. Well, I sent it loaded with tools to my son Jonathon who lives in Indiana.

I’m no where at the level of confidence most of your followers are but I am trying.

Every mistake I make is a learning experience.

So far I attempted three times to make a router plane. My expectations and image I have planted in my brain don’t match my skill level. I am getting better though. For my router plane I finally decided on a minimal design like the Rose router plane. That design is well within my skill level and I figure I can use it to make the better plane you profiled (I really want one like that). I’ll settle for what I can make until my eye hand coordination catches up with my mental visions.

I did successfully make an accurate set of dovetail guides. Now I’m working on planing with a bench plane and doing my best to use a No. 4 to make smooth and square surfaces. Don’t worry, I have a technique I’m developing for my skill level. I use a small mini plane for those sections that refuse to cooperate with my expectations.

I’m making a lot of progress between my garden and other projects. I completed my saw bench with dog holes, a shooting board, and a couple of handles for the garden tools. I’m thinking about cutting up a cheap Harbor Freight machete and turning it into a draw knife. I’m almost tempted to use a rail from an old bed frame and heat treat it if I can find a pan large enough for an oil bath. You think that would be a better choice over the Harbor Freight machete that never could hold an edge for more than 10 hacks?

After reading your series on the tool box I’m shifting gears again. You would think I was a rocket scientist with all the ideas I started envisioning. I do need a tool box more than all the other little projects I want to build.

Thank you, Paul. You’re posts are a breath of fresh air. I’ve taken a number of your methods to heart and look forward to more as I enter retirement.

Hello Paul

Great post as always, keep them coming.

I’m thinking here that you have much more to tell, not only about woodworking but also about your apprentice life.

You know, apprenticeship was once the only way to become a master in many professions, and nowadays it’s difficult to understand how someone would progress from a kid to a master by being accepted by a workshop and a master and evolving through work and mentorship up to the status of master her or himself.

In your posts we can have a glimpse of how it was, and this just made more curious. I start to wonder about the centuries past, when carpentry, furniture making, masonry, painting, sculpting, blacksmithing and so many other professions were learned this way.

It would be very interesting, and an important part of your legacy, if you could tell us about this process. How someone would be accepted as apprentice? How was the progression of the learning? Who lent the tools used in the beginning? Was it hard to get your own tools? Where there ranks, official ou unofficial, to climb? And so many other hows and whats…

Tell us all, write a book if necessary.

Best regards

this post was so moving. so much wisdom and lived experience. i want a paul sellers beehive so bad my man! make us the PS eco hive for the garden. with thr poormans tools! i really need to make long sidebars for my langstroth frame in bulk…they are so expensive now. save the bees!

Dovetails? What has amazed me is that the joints fit together now better than when I cut and glued them. Maybe I’m nuts, but something is happening. They are all in service, sitting on the shelves holding all kinds of things.

Paul-

Any chance you could do a short bit on “water tight” doevtails? Conceptually I get what they would be, but purpose and need elude me. I have never actually heard that particular phrase used before.

So in those far off days what glue was used for the dovetails? Was the glue kept brewing in a corner . I might ask if you would recommend Fish glue . Or was that called the Lazy way. Did you ever need to disassemble something already glued together ? Not dovetails obviously .

Animal glue was the predominant glue through the centuries and though many chemical, protein and plastic glues have not quite totally replaced it in general woodworking it remains the ideal glue for fine instrument making and restoration woodworking like furniture making and such. I never came across fish glue for sale, only hide glue so that’s what we used. In my apprenticeship the predominant glue was Casein glue which comes from milk protein. I was a good, natural and waterresistent glue with good open time and excellent holding properties. You mixed the powder with water and stirred thoroughly for a few mints until it started to thicken. Usually you had 10 minutes to apply and clamp the work and then you left it for a few hours to thoroughly dry and then it dried to a brittle hard.

Watertight is just an exaggeration airtight as the water in the glue expands the wood fibres on mating surfaces to become gap free. And yes, I have dismantled lots of furniture throuth the years and that includes dovetails. The great thing about hide glue is shocking the joint usually splits within the glue line.

Paul,

Over the years I’ve read your posts about George and the others in the shop where you apprenticed and I wonder, if you’ve every thought about setting down those stories verbally or visually?

I think it would be wonderful to have a record of those times with all of the color that a live interview can provide that words can not.

Those times you describe are long gone but may of us would love to hear about them in more detail than you’ve documented in the past. During your recuperation time, perhaps you may find a way to film some interviews on those times. They would be a valuable historical document at the very least.

Thank you for all you do and all you’ve given me over the years.

I tend to agree, “History” tends to be more about Kings and Queens, and battles, but working people are often absent.

Paul, I think your blog post on 12 Jul 2013 has a photo of the chest you worked on during class. The image name is DSC_0667.jpg Does that help you search your archive for the photos you’re seeking? My class notes start on 8 Jul 2013 (rather than 2012) for the tool chest. That should be close to when you’d have started yours in class.

I remember you doing some extra things on yours just so that we could see various options. You added cockbead to the drawer fronts and some decorative stringing around perimeter of the upper storage area (and maybe in the drawers?).

You used an improvised tool to thickness the various layers of the stringing. It was a card scraper clamped to a block and I remember that having some sort of progressive angle was important, but I didn’t take any notes or photos or make a sketch, so I’ve completely lost this technique. I think you would saw a strip (maybe from a narrow tongue ?) and then you had a method to bring it to thickness with this improvised tool that was very simple, very obvious, but clearly very easy to forget!

I just sent you an email with pic of my setup for cardscraper thicknesser, Ed. Just in case it goes to spam.

Got it! Many thanks!

Hello Ed. I just put a whole blog post up on this card scraper thicknesser.

This is my favorite blog of yours to date. Bringing us into such a formative moment of your early development while, simultaneously, sharing wisdom you have accumulated through stunning photography and hard-earned trade craft, was riveting and inspiring to read. Hearing about the beginning of your craft while seeing results of a lifetime of skill is very impactful.

As a novice, I felt something akin to victory (not fun) when my first dovetails went together building your shaker candle box from YouTube.

This post really resonates with me. Thank you so much for sharing.

Paul, this weeks writeup struck a cord with me. Your description of how you felt was exactly the way I felt, even though I worked in a completely different field, computer programmer. I set most of my goals, had nobody coming looking over my shoulder, and if they did, their eyes soon glazed over at the first actual detail of what I was working on , or the plan for next week.

I just felt the accomplishment of the challenge of a new task.

It just proves that the way you feel about your work is mainly internal and not the province of the actual work being performed.

Thank you for this write up. That feeling is mostly missing for me today. I had forgotten how good I used to feel with the challenges.

Thank you again.

Clarence

Hi paul,

I’m starting my training as a joiner next year, dead excited about it. I’d love to make a fall front joiners tool box, I’ve seen a slightly larger version than travelling one, in a few pictures and blog posts of yours. what dimensions would you recommend?

kind regards

Jack